Abstract

Background

Exercise therapy is widely used as an intervention in low‐back pain.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of exercise therapy in adult non‐specific acute, subacute and chronic low‐back pain versus no treatment and other conservative treatments.

Search methods

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 3, 2004), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychInfo, CINAHL databases to October 2004; citation searches and bibliographic reviews of previous systematic reviews.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials evaluating exercise therapy for adult non‐specific low‐back pain and measuring pain, function, return‐to‐work/absenteeism, and/or global improvement outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently selected studies and extracted data on study characteristics, quality, and outcomes at short, intermediate, and long‐term follow‐up.

Main results

Sixty‐one randomized controlled trials (6390 participants) met inclusion criteria: acute (11), subacute (6) and chronic (43) low‐back pain (1 unclear). Evidence was found of effectiveness in chronic populations relative to comparisons at all follow‐up periods; pooled mean improvement was 7.3 points (95% CI, 3.7 to 10.9) for pain (out of 100), 2.5 points (1.0 to 3.9) for function (out of 100) at earliest follow‐up. In studies investigating patients (i.e. presenting to healthcare providers) mean improvement was 13.3 points (5.5 to 21.1) for pain, 6.9 (2.2 to 11.7) for function, representing significantly greater improvement over studies where participants included those recruited from a general population (e.g. with advertisements). There is some evidence of effectiveness of graded‐activity exercise program in subacute low‐back pain in occupational settings, though the evidence for other types of exercise therapy in other populations is inconsistent. There was evidence of equal effectiveness relative to comparisons in acute populations [pain: 0.03 points (95% CI, ‐1.3 to 1.4)].

Limitations: This review largely reflects limitations of the literature, including low quality studies with heterogeneous outcome measures, inconsistent and poor reporting, and possibility of publication bias.

Authors' conclusions

Exercise therapy appears to be slightly effective at decreasing pain and improving function in adults with chronic low‐back pain, particularly in healthcare populations. In subacute low‐back pain there is some evidence that a graded activity program improves absenteeism outcomes, though evidence for other types of exercise is unclear. In acute low‐back pain, exercise therapy is as effective as either no treatment or other conservative treatments.

Plain language summary

Exercise therapy for treatment of non‐specific low back pain

Exercise therapy appears to be slightly effective at decreasing pain and improving function in adults with chronic low‐back pain, particularly in populations visiting a healthcare provider. In adults with subacute low‐back pain there is some evidence that a graded activity program improves absenteeism outcomes, though evidence for other types of exercise is unclear. For patients with acute low‐back pain, exercise therapy is as effective as either no treatment or other conservative treatments.

Background

Low‐back pain is one of the leading causes of disability. Exercise therapy is a management strategy that is widely used in low‐back pain. It encompasses a heterogeneous group of interventions ranging from general physical fitness or aerobic exercise, to muscle strengthening, various types of flexibility and stretching exercises.

In 2000, van Tulder et al. published a Cochrane review of the literature assessing the effectiveness of exercise therapy for low‐back pain for pain intensity, functional status, overall improvement and return to work (van Tulder 2000b). It included 39 randomized controlled trials of all types of exercise therapy for individuals with acute and chronic non‐specific low‐back pain. They synthesized the evidence using a levels‐of‐evidence approach due to the heterogeneity and insufficiency of the literature, concluding that the evidence did not support effectiveness of exercises for acute low‐back pain, but it may be helpful for chronic low‐back pain. Since the completion of their systematic review, a substantial number of new trials have been published. Recent reviews on related topics have been restricted by population (Hilde 1998, Liddle 2004, Kool 2004) or type of exercise therapy (Ernst 2003) and have used only qualitative methods of synthesis (Hilde 1998, Liddle 2004, Ernst 2003, Abenhaim 2000). Recent clinical guidelines that included exercise therapy for low‐back pain used quantitative methods to synthesize results of randomized controlled trials, controlled trials and observational studies (Tugwell 2001), however only 12 studies overlap with the 61 trials included in this review. There is a need for an updated review on this topic. Cautious use of quantitative meta‐analysis for direct and indirect comparisons, employed in appropriate subgroups will be informative to synthesize this literature.

Objectives

The primary objective of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness of exercise therapy for reducing pain and disability in adults with non‐specific acute, subacute and chronic low‐back pain compared to no treatment (including placebo and sham treatment) and other conservative treatments.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included published reports of completed randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

We included studies involving adult participants with acute (less than six weeks), subacute (six to 12 weeks), or chronic (longer than 12 weeks) non‐specific low‐back pain. We excluded studies that involved individuals with low‐back pain caused by specific pathologies or conditions.

Types of interventions

Exercise therapy was defined as "a series of specific movements with the aim of training or developing the body by a routine practice or as physical training to promote good physical health" (Abenhaim 2000). We included studies that compared exercise therapy to a) no treatment or placebo treatment, b) other conservative therapy, or c) another exercise group.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes of interest were self‐reported pain intensity, condition‐specific physical functioning and global improvement, and return to work/absenteeism. Outcome assessment data were abstracted for three time periods: short‐term (post‐treatment assessment closest to six weeks after randomization, not longer than 12 weeks), intermediate (six months), and long‐term follow‐up (12 months or more).

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 3, 2004) and these electronic databases: MEDLINE and EMBASE (up to October 2004), PsychInfo and CINAHL (1999 to October 2004). We conducted citation searches, screened cited references of exercise reviews and contacted content experts for additional trials. We did not restrict the searches or inclusion criteria to any specific language (see Appendix 1; Appendix 2 for full strategy).

Data collection and analysis

Study selection and data abstraction

A standard protocol was followed for study selection and data abstraction (van Tulder 2003). This included two reviewers' independent assessment of study eligibility, data extraction, assessment of trial quality and clinical relevance. Consensus and, if necessary, a third reviewer were used to resolve disagreements. We extracted population characteristics (patient population source or setting, study inclusion criteria, duration of low‐back pain episode, and age of patients), intervention characteristics (description and types of exercise therapy, duration and number of treatment sessions, intervention delivery type, and co‐interventions) outcome data, and overall conclusions about the effectiveness of the exercises onto pre‐tested standardized forms. Assessment of quality included: appropriate randomization, adequate concealment of treatment allocation, adequacy of follow‐up, and outcome assessment blinding (Jadad 1996). High quality studies were defined as those in which all of these key quality criteria were met. Clinical relevance of each trial was assessed with four items: participants described in detail to assess clinical comparability, interventions and treatment settings adequately described to allow repetition, clinically relevant outcomes measured and reported, and are likely treatment benefits worth potential harms. Reviewers were not blinded to authors, institution or journal of publication due to feasibility and because they were familiar with most of the literature. Authors of published trials were contacted to clarify or provide additional information if the study provided insufficient information.

Analysis

We discussed the analyses of study results with clinical content experts. We synthesized the earliest outcomes provided for acute, subacute and chronic low‐back pain, comparing exercise to no treatment and to other conservative treatment, and overall for short, intermediate and long‐term follow‐up periods. Due to important gaps in the reporting of return‐to‐work/absenteeism and global assessment, quantitative analyses were only possible for pain and functioning outcomes. In the low‐back pain literature, several outcome measures are used to assess the constructs of pain intensity (for example, 10 mm or 100 mm visual analogue scales [VAS], or 0 to 10 numerical rating scale [NRS]) (see recent review by Von Korff et al (von Korff 2000)) and condition‐specific functioning (for example, the 24‐point Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, or the Oswestry Disability Index scored out of 100) (see recent review by Kopec (Kopec 2000)). There is moderate to high correlation between the different measures of the two constructs. In this review, individual trial outcomes for pain and functioning were re‐scaled to 0 to 100 points [for example a VAS pain score (standard deviation) of 5.1 (2.3) out of 10 was re‐scaled to 51 (23) out of 100], where positive mean effect sizes indicated improvement (i.e. decreased pain, and decreased functional limitations). Re‐scaling is common (Kopec 2000) and facilitates comparison and interpretability of the syntheses. On the basis of current literature on minimal clinically important differences, we considered that a 20‐point (/100) improvement in pain (Salaffi 2004) and a 10‐point (/100) improvement in functioning outcomes (Bombardier 2001) were clinically important. Differences were considered statistically significant at the five percent level. The adequacy of sample size to detect these differences in each trial was assessed assuming a power of 90%.

To be consistent with the previous review and to allow more complete use of available data, we used both a qualitative rating system and quantitative meta‐analyses. The latter were conducted by pooling weighted mean differences with random effects models and data from at least three studies (DerSimonian 1986). Exercise treatment groups from included trials were included in the syntheses if they had an independent no treatment or other conservative treatment comparison group. This requirement appropriately meant studies with no comparison group (i.e. trials that contrast multiple exercise therapy groups only) were not included and comparison groups were not "double counted" in the meta‐analyses. This latter criteria is necessary to avoid correlation in effect sizes resulting from the use of repeated comparison data. We extracted data on means or median follow‐up outcomes for study groups. To maximize the available data, missing variance scores were imputed using the mean variance from studies with similar duration. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of excluding studies reporting median values and excluding studies that did not adequately present variance scores. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using I2 statistics and confidence intervals (Higgins 2002). Publication bias was evaluated with Egger's test and funnel plots (Egger 1997).

Qualitative assessment of results was based on primary outcome measures and considered the methodological quality and the reviewers' overall conclusions for each exercise therapy group. Exercise therapy groups were included in the qualitative synthesis if the trial included a no treatment or other conservative treatment comparison group. Two reviewers independently rated the findings for each exercise therapy group. Studies were considered to be providing evidence of effectiveness if statistically significant improvement was observed in at least one of the key outcomes in favour of the exercise group and clinically important improvement was observed within or between groups. Studies were considered to be providing evidence that the exercise therapy was ineffective if there was statistically significant improvement of the comparison group and no clinically important improvement within the exercise group. We rated studies neutral if no statistically and clinically significant results were observed and unclear if insufficient data were presented. A consensus process was used to examine patterns in trial results. Levels of evidence, as recommended by the Back Group (van Tulder 2003), were used:

1. Strong evidence ‐ consistent findings* in multiple high quality trials

2. Moderate evidence ‐ consistent findings in multiple low quality trials and/or one high quality trial

3. Limited evidence ‐ one low quality trial

4. Conflicting evidence ‐ inconsistent findings in multiple trials.

5. No evidence ‐ no randomized trials available.

*Consistent findings were defined as 75% or more trials (66% in sensitivity analysis) showing results in the same direction.

Further analyses explored heterogeneity due to study‐level variables, such as population source and study quality. We characterized the population sources as healthcare (primary, secondary or tertiary care centres), occupational (patients presenting to occupational healthcare facilities or personnel in compensatory situations), or from a general or mixed population (e.g. including individuals recruited by newspaper advertisements) to differentiate the studies with patients in typical treatment settings (healthcare and occupational) from those including individuals with low‐back pain who may not normally present for treatment. Outcomes for subgroups of studies conducted in these populations were compared (Song 2003). The impact of study quality on effect sizes was assessed using subgroup analysis.

SAS for Windows Version 8 (for descriptive), STATA 8 (for publication bias), and Review Manager 4.2 packages were used for analyses.

Results

Description of studies

Additional Figure 1 shows details of included and excluded studies. Additional Table 1 contains the descriptive summary and characteristics of the 61 studies included (Alexandre 2001; Aure 2003; Buswell 1982; Bendix_a 2000; Bendix_b 1995; Bronfort 1996; Bentsen 1997; Cherkin 1998; Chok 1999; Calmels 2004; Davies 1979; Deyo 1990; Delitto 1993; Dalichau 2000; Descarreaux 2002; Elnaggar 1991; Farrell 1982; Faas 1993; Frost 1995; Frost 2004; Gilbert 1985; Gur 2003; Galantino 2004; Hansen 1993; Hemmila 1997; Hides 1996; Hildebrandt 2000; Johanssen 1995; Jousset 2004; Kendall 1968; Kankaanpaa 1999; Kuukkanen 2000; Lidström 1970; Lindstrom 1992; Ljunggren 1997; Lie 1999; Manniche 1988; Malmivaara 1995; Mannion 1999; Moffett 1999; Moseley 2002; Niemisto 2003; Preyde 2000; Petersen 2002; Risch 1993; Rasmussen‐Barr 2003; Rittweger 2002; Stankovic 1990; Seferlis 1998; Soukup 1999; Storheim 2003; Staal 2004; Turner 1990; Torstensen 1998; Tritilanunt 2001; Underwood 1998; Waterworth 1985; Yeung 2003; Yelland 2004; Yozbatiran 2004; Zylbergold 1981). A complete description of these studies is presented in the Table of Included Studies.

1.

1. Summary of Included Studies.

| Characteristic | All Studies (n=61) | Acute (n=11) | Subacute (n=6) | Chronic (n=43) |

| Population source: | ||||

| ‐ Healthcare | 33 (54) | 7 (78) | 3 (50) | 22 (51) |

| ‐ Occupational | 12 (20) | 2 (22) | 3 (50) | 7 (16) |

| ‐ General Population | 7 (11) | 0 | 0 | 7 (16) |

| ‐ Mixed | 7 (11) | 0 | 0 | 7 (16) |

| Age of study population: Mean years (95% CI) | 41 (39 to 42) | 38 (35 to 40) | 38 (32 to 44) | 42 (40 to 44) |

| % Male of study population | 0.49 (0.45, 0.55) | 0.56 (0.46, 0.66) | 0.63 (0.42, 0.84) | 0.46 (0.39, 0.52) |

| Observed duration of low back pain: Mean (95% CI) | 4.5 years (2.6 to 6.3) | 8 days (5 to 11) | 12 weeks (n/a) | 5.6 years (3.4 to 7.8) |

| Observed severity of pain at baseline: Mean /100 (95% CI) | 47 (43, 51) | 45 (36, 53) | 56 (33, 78) | 46 (41, 50) |

| Outcome measures assessed: | ||||

| ‐ Pain | 52 (85) | 10 (91) | 6 (100) | 36 (84) |

| ‐ Functional abilities | 46 (75) | 9 (82) | 4 (67) | 33 (77) |

| ‐ Work status | 21 (34) | 5 (45) | 6 (100) | 9 (21) |

| ‐ Global assessment | 13 (21) | 3 (27) | 1 (17) | 7 (16) |

| Cost evaluation information presented | 8 (13) | 2 (18) | 2 (33) | 4 (9) |

| Adverse effects assessed: | ||||

| Any reported | 14 (23) | 2 (18) | 2 (33) | 10 (23) |

| Negative reported | 10 (16) | 2 (18) | 1 (17) | 7 (16) |

| Study quality: Studies satisfying key items | ||||

| All 4 | 8 (13) | 1 (9) | 1 (17) | 6 (14) |

| Any 3 | 18 (30) | 4 (36) | 3 (50) | 10 (23) |

| Any 2 | 15 (25) | 2 (18) | 2 (33) | 11 (26) |

| Any 1 | 15 (25) | 3 (27) | 0 | 12 (28) |

| None | 5 (8) | 1 (9) | 0 | 4 (9) |

| * Study populations were classified according to most appropriate category based on inclusion criteria and reported duration. Thirteen studies included subjects with mixed duration of low back pain. |

The pain and function outcomes for each trial are presented in Appendix Table 2 (available at www.annals.org). The VAS scale (/100) was the most common outcome measure used to assess pain across studies (22 studies), and 83% of studies reporting pain used one of: VAS (/100), VAS (/10), NRS (/100) or NRS (/10). Other pain outcome measures included the McGill pain questionnaire (four studies), a five‐ or nine‐point Likert pain scale, the Aberdeen pain scale, and the West Haven Yale questionnaire (one study each). The most common functional limitation outcome measures, employed in 59% of trials, were the Oswestry disability index (15 studies) and the Roland Morris disability questionnaire (12 studies). Other functional measures included: VAS function scale (four studies), activities of daily living scale (three studies), sickness impact profile (two studies), Quebec disability index (two studies), Manniche's low‐back rating scale (two studies), and five additional scales that were each used in single trials. The mean follow‐up times (95% confidence interval (95% CI)) for each of the short, intermediate, and long‐term follow‐up periods were 6.3 weeks (95% CI: 5.3 to 7.3), 21.0 weeks (95% CI: 18.4 to 23.6), and 53.6 weeks (95% CI: 48.7 to 58.6), respectively.

Risk of bias in included studies

In the original review, which assessed ten quality items, including the four key items investigated in the current review, the reviewers disagreed on 122 of the 351 quality assessment scores (35%). Disagreements were resolved by consensus in most cases, and a third reviewer only had to make a final decision twice. In the update, the reviewers disagreed on 19 of the 124 key item scores (15%), resulting in a Kappa score of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.67 to 0.86), indicating high agreement. For the update, disagreements were resolved by consensus in all cases except two, when a third reviewer was needed to reach a decision.

Only eight studies scored 'positive' on all the four key validity criteria (Deyo 1990; Frost 1995; Frost 2004; Hansen 1993; Lindstrom 1992; Malmivaara 1995; Manniche 1988; Mannion 1999; Torstensen 1998). Based on information in the published report, 37 of the key quality items assessed (15%) were initially rated as unclear (the most common item with insufficient description was 'adequate concealment of treatment allocation'). Contacting the authors of the trials supplemented this information, modifying 14% of the criteria for which responses were received.

Clinical relevance of the included studies

Assessment of clinical relevance found that many of the trial publications supplied inadequate information. The study population was adequately described by 90% of the publications, but only 54% adequately described the exercise intervention. There was adequate reporting of relevant outcomes in 70% of the trials. A small number of studies reported on the presence or absence of adverse events (16 studies, 26%). Twelve studies reported mild negative reactions to the exercise program, such as increased low‐back pain and muscle soreness, in a minority of patients. Due to limitations of reporting, it was not possible to assess the treatment benefit to harm ratio.

Effects of interventions

Complete meta‐analysis data, Forest plots and results are provided in the 'Tables: Comparisons and data' section.

Effectiveness

Acute low‐back pain populations

Ten of 11 trials involving 1192 adults with acute low‐back pain had non‐exercise comparisons. These trials provided conflicting evidence: one high quality trial conducted in an occupational setting found mobilizing home‐exercises to be less effective than usual care (Malmivaara 1995) and one low quality trial conducted in a healthcare setting found a therapist‐delivered endurance program improved short‐term functioning more than no treatment (Chok 1999). Of the remaining eight low quality trials, six found no statistically significant or clinically important differences between exercise therapy and usual care or no treatment; the results of two trials were unclear. We rated these trials as low quality most commonly because of inadequate assessor blinding. There was inadequate power to detect clinically important differences in pain for one trial (Underwood 1998) and for functioning in five trials (Farrell 1982; Hides 1996; Seferlis 1998; Underwood 1998; Waterworth 1985).

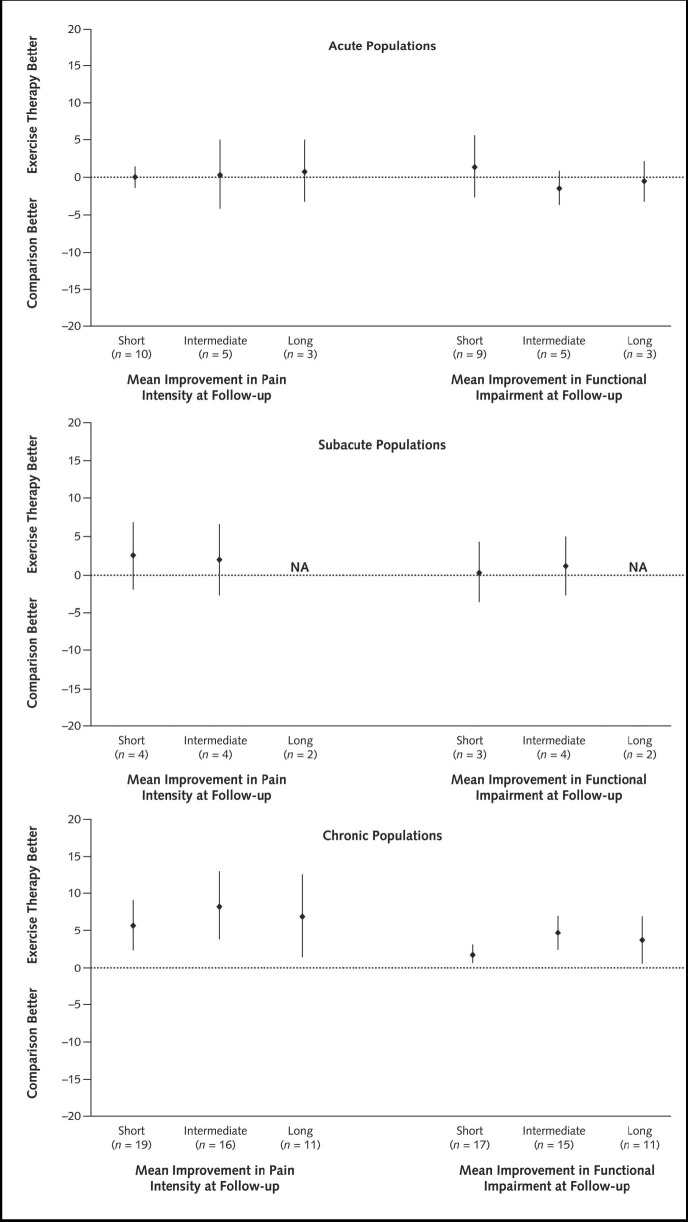

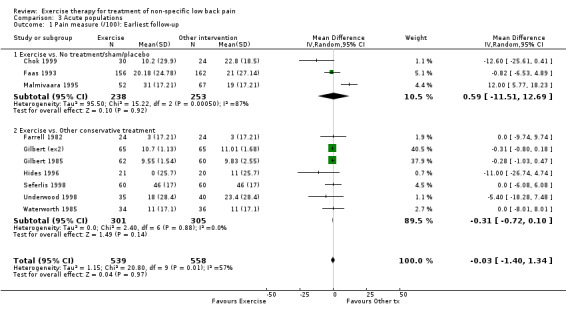

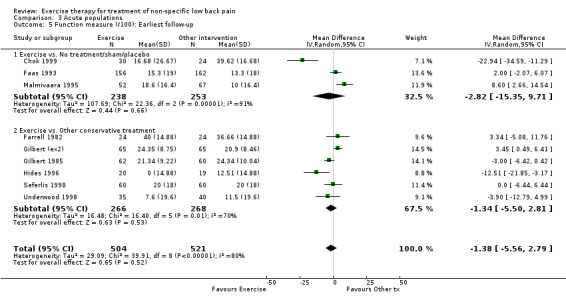

The pooled analysis of trials with adequate numeric data failed to show a difference in short‐term pain relief between exercise therapy and no treatment (three trials), with an effect of ‐0.59 points/100 (95% CI: ‐12.69 to 11.51). There was no difference at earliest follow‐up in pain relief when compared to other conservative treatments (seven trials): 0.31 points (95% CI: ‐0.10 to 0.72) [vs. all comparisons (10 trials) 0.03 points (95% CI: ‐1.34 to 1.40)]. Similarly, there was no significant positive effect of exercise on functional outcomes. Outcomes show similar trends at the three follow‐up periods in this population, as shown in Figure 2.

2.

Subacute low‐back pain populations

In six studies involving 881 individuals with subacute low‐back pain, seven exercise groups had non‐exercise comparisons. One high quality and one low quality trial each found reduced absenteeism outcomes with a graded‐activity intervention in the workplace compared to usual care (Lindstrom 1992; Staal 2004). This provides moderate evidence of effectiveness of a graded‐activity exercise program in subacute low‐back pain in occupational settings. One low quality trial found improved functioning over usual care with an exercise program combined with behavioural therapy (Moffett 1999). Two trials with inadequate assessor blinding were rated neutral, although they were adequately powered to detect clinically important differences in at least one primary outcome (Cherkin 1998; Storheim 2003). The results of one trial were unclear (Davies 1979). The evidence is conflicting about the effectiveness of other types of exercise therapy in subacute low‐back pain compared to other treatments.

Meta‐analysis of pain outcomes at the earliest follow‐up, including five studies with available data, resulted in a pooled weighted mean difference in pain score of 1.89 points (95% CI: ‐1.13 to 4.91) relative to any comparison. The pooled analysis of four trials presenting data on functional outcomes found a mean difference of 1.07 points (95% CI: ‐3.18 to 5.32) relative to other comparisons. There is insufficient evidence to support or refute the effectiveness of exercise therapy in subacute low‐back pain for reducing pain intensity and improving function. Results for short and intermediate follow‐up periods in this population are shown in Figure 2.

Chronic low‐back pain populations

In 43 trials including 3907 individuals with chronic low‐back pain, 33 exercise groups had non‐exercise comparisons. These trials provide strong evidence that exercise therapy is at least as effective as other conservative interventions, and conflicting evidence that exercise therapy is more effective than other treatments for chronic low‐back pain. Two exercise groups in high quality studies and nine groups in low quality studies found that exercise was more effective than comparison treatments. These studies, mostly conducted in healthcare settings, commonly used exercise programs that were individually designed and delivered (as opposed to independent home exercises) (Bendix_b 1995; Frost 1995; Hildebrandt 2000; Moseley 2002; Niemisto 2003; Risch 1993). The exercise programs commonly included strengthening or trunk stabilizing exercises (Frost 1995; Kankaanpaa 1999; Moseley 2002; Niemisto 2003; Preyde 2000; Risch 1993). Conservative care in addition to the exercise therapy was often included in these effective interventions, including behavioural and manual therapy, advice to stay active and education. One low quality trial found a group‐delivered aerobics and strengthening exercise program resulted in less improvement in pain and function outcomes than behavioural therapy (Bendix_b 1995). Of the remaining trials, fourteen (two high quality and twelve low quality) found no statistically significant or clinically important differences between exercise therapy and other conservative treatments. Four of these trials were inadequately powered to detect clinically important differences on at least one outcome (Alexandre 2001; Rasmussen‐Barr 2003; Yelland 2004; Zylbergold 1981). Trials were most commonly rated as low quality because of inadequate assessor blinding. Meta‐analysis of pain outcomes at the earliest follow‐up included 23 exercise groups with an independent comparison and adequate data. Synthesis resulted in a pooled weighted mean improvement of 10.2 points (95% CI: 1.31 to 19.09) for exercise therapy compared to no treatment, and 5.93 points (95% CI: 2.21 to 9.65) compared to other conservative treatment [compared to all comparisons 7.29 points (95% CI: 3.67 to 10.91)]. At the earliest follow‐up, smaller improvements were seen in functional outcomes with an observed mean positive effect of 3.00 points (95% CI: ‐0.53 to 6.48) compared to no treatment, and 2.37 points (95% CI: 0.74 to 4.0) compared to other conservative treatment, at the earliest follow‐up [compared to all comparisons 2.50 points (95% CI: 1.04 to 3.94)]. Results considering different follow‐up periods were similar for pain and functional outcomes (Figure 2). Egger's test suggested there may be publication bias among studies in chronic populations (p = 0.015); funnel plot analysis showed this was likely due to three studies that demonstrated highly variable, large positive effects (Alexandre 2001; Bendix_a 2000; Dalichau 2000).

Sensitivity analyses for qualitative syntheses did not affect the conclusions. Meta‐analyses were conducted excluding the results of studies that presented data as median scores (Bendix_b 1995; Chok 1999; Hansen 1993; Rasmussen‐Barr 2003), or did not provide variance scores (Dalichau 2000; Farrell 1982; Hemmila 1997). This did not impact the pooled results for acute and subacute populations. In chronic populations, this sensitivity analysis resulted in lower, though still significantly improved, pooled effect sizes. Complete results of all analyses are available on request.

Further Analyses

Analyses were conducted on studies from acute, subacute and chronic populations to assess the impact of study level variables. Test of statistical heterogeneity of pain outcomes found 57% (95% CI: 12 to 79), 37% (95% CI: 0 to 76) and 81% (95% CI: 72 to 87) for acute, subacute and chronic, respectively, of the heterogeneity not due to chance; function outcomes showed 80% (95% CI: 63 to 89), 47% (95% CI: 0 to 82) and 52% (95% CI: 19 to 71), respectively. To account for heterogeneity, random effects models were used and clinically relevant subgroups of studies investigated. A complete exploration of intervention heterogeneity is included in an earlier publication (Hayden 2005b).

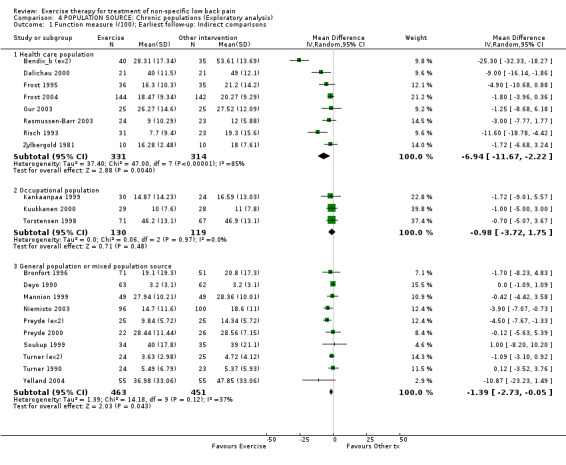

Indirect subgroup comparisons using qualitative synthesis and meta‐analysis found trials examining healthcare study populations observed higher mean improvements in functioning and pain over their comparison groups than trials examining occupational or general populations. In chronic populations, there were mean improvements in healthcare settings of 13.3 points (95% CI: 5.5 to 21.1) on pain and 6.9 points (95% CI: 2.2 to 11.7) on function outcomes. The adjusted differences between studies with different source populations found significantly greater improvement in outcomes in healthcare populations compared to studies from general population or mixed populations, with a mean of 9.96 points (95% CI: 1.6 to 18.4) more improvement in pain, and 5.52 points (95% CI: 0.6 to 10.4) greater improvement in functioning.

Meta‐analyses were conducted on the subgroup of high quality trials. The observed effectiveness of exercise therapy decreased and only remained significant for pain outcomes in the chronic population.

Discussion

The current review is the most up‐to‐date assessment of the effectiveness of exercise therapy in key population subgroups. For the most part, results were similar using either a qualitative rating system or meta‐analysis. We draw the following conclusions, which provide useful information for primary care clinicians to help guide their patient management and referral practices:

1. In acute low‐back pain, there is evidence that exercises are not more effective than other conservative treatments. Meta‐analysis showed no advantage over no treatment for pain and functional outcomes over the short or long‐term.

2. There is moderate evidence of effectiveness of a graded‐activity exercise program in subacute low‐back pain in occupational settings. The effectiveness for other types of exercise therapy in other populations is unclear.

3. In chronic low‐back pain, there is strong evidence that exercise is at least as effective as other conservative treatments. Individually designed strengthening or stabilizing programs appear to be effective in healthcare settings. Meta‐analysis found functional outcomes significantly improved, however, the effects were very small, with less than a three‐point (out of 100) difference between the exercise and comparison groups at earliest follow‐up. Pain outcomes were also significantly improved in groups receiving exercises relative to other comparisons, with a mean of approximately seven points. Effects were similar over longer follow‐up though confidence intervals increased. Mean improvements in pain and functioning may be clinically meaningful in studies from healthcare populations in which improvements were significantly greater than those observed in studies from general or mixed populations.

This study has several strengths and also some limitations. A large number of randomized controlled trials informed this study and the data were collected in a systematic way within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration, giving confidence that the synthesis represents the current state of the literature. However, limitations in the quality and reporting of the trials are notable. Only a small number of the studies were rated as high quality and this may have led to an overestimation of effect. Also, many studies lacked information to assess quality and clinical relevance. Contacting the authors of the trials provided missing data, emphasizing the importance and usefulness of this practice. The only outcome measure used in the majority of studies was pain intensity (in 85%), limiting the ability to report on other important outcomes. In 1998, a group of back pain researchers made recommendations for standardized use of outcome measures in back pain research, suggesting a minimum of pain, functional status and general health measures (Deyo 1998). It is disappointing to observe the lack of consistency, and the fact that only three‐quarters of the studies in this review included a measure of functional status and 15% a measure of general health. Journals in the field of back pain should adopt reporting guidelines (Begg 1996) and, even more important, use them in their review process, to improve the quality of future reports of trials in this field. We found potential publication bias in studies in chronic low‐back pain; this may have resulted in an overestimation of the effectiveness of exercise therapy in this population. Initiatives in other fields to register randomized controlled trials will also be important in low‐back pain research. We employed both qualitative and quantitative synthesis strategies in this review, which was informative. Qualitative synthesis methods facilitate the inclusion of results from trials which inadequately report outcomes. This is particularly useful when only a small number of studies are available, for example, in subacute populations in the current review. However, the qualitative synthesis was more challenging in assessing the evidence in chronic populations, where a large number of studies were available.

With meta‐analysis, we found no evidence that exercise therapy is more effective than no treatment in improving outcomes in acute low‐back pain. This finding is consistent with the original Cochrane review on this topic (van Tulder 2000b) and other systematic reviews (Abenhaim 2000; Hilde 1998; Tugwell 2001). However, it should be stressed that exercise therapy is not the same as advice to stay active, which is a recommended treatment strategy in acute populations (Abenhaim 2000; Waddell 1997). In the subacute population, which was not considered separately in the original Cochrane review, there were six trials available. In a recent systematic review of various conservative interventions, Pengel et al. concluded there was an important gap in evidence for these interventions in the treatment of subacute low‐back pain (Pengel 2002). In our review, two trials looking at a working population found reduced absenteeism outcomes with a graded‐activity intervention compared to usual care (Lindstrom 1992; Staal 2004), though there continues to be uncertainty about other types of exercises and in populations seeking healthcare. We also recommend more clear definitions and further high quality research of exercise therapy in this population. Finally, our positive findings in chronic populations reflect the conclusions of earlier reviews (Abenhaim 2000; Hilde 1998; Tugwell 2001). Our quantitative analysis provides an estimate of the average treatment effect and its uncertainty, highlighting an overall small treatment benefit. Our finding of greater improvement in trials investigating healthcare populations is important. Future intervention studies should be conducted in populations that are seeking care and therefore best represent patients with low‐back pain. We do not recommend further research on the effectiveness of general exercise therapy interventions in chronic low‐back pain. Trials should investigate specific exercise intervention strategies in well defined low‐back pain patient populations (Hayden 2005b).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Evidence from randomized controlled trials demonstrates that exercise therapy is effective at reducing pain and functional limitations in the treatment of chronic low‐back pain, though cautious interpretation is required due to limitations in this literature. Overall, mean improvements in outcomes across all research settings are small, though significant, over other conservative treatment options. Clinically important improvements are more likely in healthcare settings. There is some evidence of effectiveness of a graded‐activity exercise program in subacute low‐back pain in occupational settings, though the evidence for other types of exercise therapy in other populations is unclear and further research is required. This literature suggests exercise therapy is as effective as either no treatment or other conservative treatments for acute low‐back pain.

Implications for research.

Future RCTs in the area of low‐back pain should: 1. include complete descriptions of the study populations and exercise interventions, 2. include complete reporting of meaningful outcome measures, 3. employ strategies to reduce bias, and 4. include more complete tracking (and reporting) of long‐term outcomes, including recurrences.

Feedback

re: 2000 (2) version of review, received Feb 2005

Summary

My concerns with this review stem not from its methodology, but its objectives. To this point, I refer specifically to the treatment of 'exercise therapy' as a single form of treatment, rather than a wide‐ranging and multifaceted modality that requires specific prescription. 'Exercise therapy' can mean many things to many people, and not just the unqualified. This point is illustrated by the wide range of interventions your reviewed studies include. Unfortunately, the generalisation of 'exercise therapy' and its efficacy in the management of low back pain also seems to be reflected in current guidelines to practitioners such as those published in the UK by NICE and the RCGP.

In my opinion, reviewing 'exercise therapy' as a single form of treatment detracts greatly from the interpretation of the results of this review. The attempt to stratify the data into 'flexion and/or extension exercises' and 'strength exercises', although noble, gives the reader little more information about the nature of the exercises undertaken. Although I appreciate the problems with finding sufficient similar trials on 'specific exercises' (which can also be sub‐divided into many forms; McKenzie; transversus abdominus and multifidus retraining, etc.), I would argue that by design, these studies may be too heterogeneous to combine. If the analogy could be made with drug treatments, 'general treatment with medication' would just not cut it as an objective for a systematic review of the pharmacological management of any condition.

The area of exercise prescription in the treatment of sub‐acute and chronic low back pain has undergone some major developments in the last 10 years. Yet unfortunately, growing bodies of high quality research into specific exercise therapy for LBP, such as that undertaken initially by a group of physiotherapists from the University of Queensland in Australia (P Hodges, C Richardson, G Jull and J Hides, and repeated successfully by other authors ‐ transversus abdominus and multifidus retraining in the treatment of low back pain), has been ignored by a large proportion of the medical community undertaking clinical trials (the UK Beam trial which recently concluded is a good example of this) and funding bodies alike. Similar highly specific exercise such as advocated by these authors requires rigorous assessment by RCT's rather than the 'blanket response' to exercise therapy most research and current 'good practice guidelines' seem to be focusing on. Time after time, insensitive interventions such as 'exercise' are tested in low back pain sufferers with understandably conflicting results, serving only to confuse practitioners and patients and fruitlessly drain research funds.

I and many of my colleagues would argue strongly that 'exercise prescription' is as broad a term as 'drug prescription'; and as such it's assessment in clinical trials requires explicit and repeatable measures such as required in drug trials (explicit description, type, dose and side‐effects etc.). I would argue that until we can assess each explicit exercise form, we have a 'general idea' what exercise can do but no more. Considering their ramifications, recommendations such as those given in your article must be given with great caution. At the very least they must realise their own limitations to interpretation and external validity. I would certainly like to see references to 'exercise' in ALL RCT's on this topic narrowed in their definitions and I feel large RCT's and subsequent systematic reviews need to be undertaken to investigate the growing body of evidence supporting the effectiveness of highly specific exercises in the management of LBP.

Reply

You have identified an argument that rages within the systematic review field ... when to 'lump' and when to 'split'. All exercises are again included in the upcoming update of the exercise review. To this point, the research question has been 'is exercise of any benefit to individuals with low back pain' ... there has not been a breakdown of each type of exercise for each duration of symptoms, due in part to the lack of data for each comparison, once one starts breaking it down to this degree, although I think the authors may have attempted some sub‐group analysis. As the literature increases, I suspect it will become more feasible to split into different research questions, addressing the efficacy of specific exercises for specific sub‐groups of individuals with low back pain. There have been some attempts to do this, but the data is still sparse and results must be treated with caution. The authors recognize that this continues to pose a challenge to clinicians who deliver exercise therapy. We cannot comment on how the summary of the scientific literature is used in the development of guidelines, since guidelines must take more into consideration than just the available evidence.

I will pass on your comments to the authors of the updated review for their consideration. Please do not hesitate to contact me should you have any further concerns once the updated review is published.

Contributors

Michael Noonan, Occupation Physiotherapist/Medical Student Victoria Pennick, Back Group Coordinator

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 19 January 2011 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1997 Review first published: Issue 2, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 23 November 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 8 September 2008 | Amended | Contact details updated |

| 17 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 30 April 2005 | New search has been performed | Compared to the previous version of this review, several changes have been made: 1. Search of CINAHL electronic database was included. 2. Trials were excluded if they investigated individuals with low back pain caused by specific pathologies and conditions; pseudo‐randomized trials were excluded. 3. Subgroup analysis of study populations included acute (<6 weeks), subacute (6 to 12 weeks), and chronic (>12 weeks) nonspecific low back pain. 4. Assessment of methodological quality included appropriate randomization, adequate concealment of treatment allocation, adequacy of follow‐up, and outcome assessment blinding. We defined high‐quality studies as those that met all of these key quality criteria. 5. Clinical relevance was assessed. 6. Analysis included both a qualitative rating system and quantitative meta‐analyses. Further analyses explored heterogeneity due to study‐level variables, such as population source and study quality and an accompanying paper explored intervention heterogeneity using Bayesian meta‐regression analysis. |

| 30 April 2005 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Thirty‐two new trials (3021 participants) were included in this update (10 previously included studies were excluded). Overall, the conclusions remain unchanged regarding the effectiveness of exercise therapy in adults with chronic low back pain, though meta‐analysis shows that these effects are modest. More improvement was found in trials investigating healthcare populations. There is some evidence suggesting a graded‐activity program improves absenteeism outcomes in subacute low back pain, although evidence for other types of exercise is unclear. In acute low back pain populations, conclusions ‐ that exercise therapy has similar effects as other conservative management and no treatment ‐ remain unchanged. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs Jens Ivar Brox and Jan Lonn, and Mr. Arne Naess for their assistance with the quality assessment and data extraction from non‐English language studies, the Physiotherapy 'Educational Influentials' from the Institute for Work & Health for their guidance with syntheses, Emma Irvin, medical librarian at the Institute for Work & Health, for her assistance with the search strategy, Victoria Pennick for her assistance with editing, and Rosmin Esmail for her contribution to the original version of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1. exp Exercise Movement Techniques/ 2. Exercise Therapy/ 3. Physical Fitness/ 4. exp EXERTION/ 5. RECREATION/ 6. exercis$.mp. 7. McKenzie$.mp. 8. Alexander.mp. 9. William$.mp. 10. Feldendrais.mp. 11. or/1‐10 12. limit 11 to randomized controlled trial 13. Randomized Controlled Trials/ 14. double blind method/ or single‐blind method/ 15. Random Allocation/ 16. PLACEBOS/ 17. Research Design/ 18. ((singl$ or doubl$ or tripl$ or trebl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).mp. 19. placebo$.mp. 20. random$.mp. 21. volunteer$.mp. 22. or/13‐21 23. exp Back Pain/ or back pain.mp. 24. backache.mp. 25. (lumbar adj pain).mp. 26. (lumbar adj trauma).mp. 27. lumbosacral.mp. 28. dorsalgia.mp. 29. sciatica.mp. 30. or/23‐29 31. 11 and 22 32. 12 or 31 33. 32 and 30 34. limit 33 to (human)

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

1. clinical article/ 2. clinical study/ 3. clinical trial/ 4. controlled study/ 5. randomized controlled trial/ 6. major clinical study/ 7. double blind procedure/ 8. multicenter study/ 9. single blind procedure/ 10. placebo/ 11. or/1‐10 12. allocat$.mp. 13. assign$.mp. 14. blind$.mp. 15. (clinic$ adj25 (study or trial)).mp. 16. compar$.mp. 17. control$.mp. 18. cross?over.mp. 19. factorial$.mp. 20. follow?up.mp. 21. placebo$.mp. 22. random$.mp. 23. ((singl$ or doubl$ or tripl$ or trebl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).mp. 24. trial$.mp. 25. (versus or vs).mp. 26. or/12‐25 27. low back pain/ 28. backache/ 29. back pain.mp. 30. backache.mp. 31. or/27‐30 32. kinesiotherapy/ 33. exp Physical Activity/ 34. exp EXERCISE/ 35. REHABILITATION/ 36. exercise$.mp. 37. McKenzie$.mp. 38. Alexander.mp. 39. William$.mp. 40. Feldendrais.mp. 41. yoga.mp. 42. or/32‐41 43. 11 or 26 44. 31 and 42 and 43 45. limit 44 to (human and yr=1999‐2002) 46. limit 45 to yr=1999 47. limit 45 to yr=2000 48. limit 45 to yr=2001 49. from 48 keep 1‐144 50. 45 not (46 or 47 or 48) 51. from 50 keep 1‐58 52. 44 53. limit 52 to (human)

Data and analyses

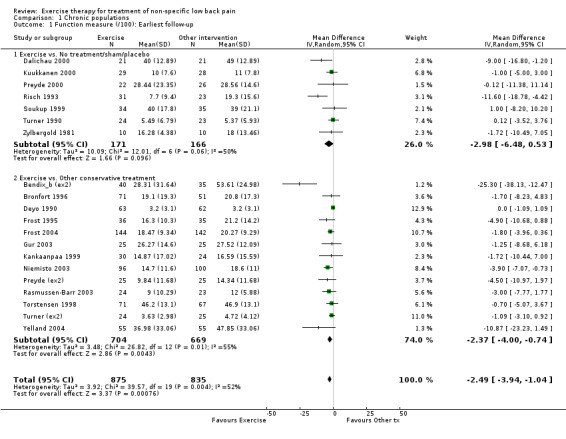

Comparison 1. Chronic populations.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Function measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up | 20 | 1710 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.49 [‐3.94, ‐1.04] |

| 1.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 7 | 337 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.98 [‐6.48, 0.53] |

| 1.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 13 | 1373 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.37 [‐2.00, ‐0.74] |

| 2 Function measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization) | 17 | 1370 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.75 [‐2.94, ‐0.56] |

| 2.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 6 | 268 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.03 [‐6.35, 0.28] |

| 2.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 11 | 1102 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.81 [‐1.62, ‐0.00] |

| 3 Function measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization) | 15 | 1401 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.64 [‐5.00, ‐2.27] |

| 3.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 4 | 216 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.84 [‐7.06, ‐0.61] |

| 3.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 11 | 1185 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.07 [‐7.91, ‐2.23] |

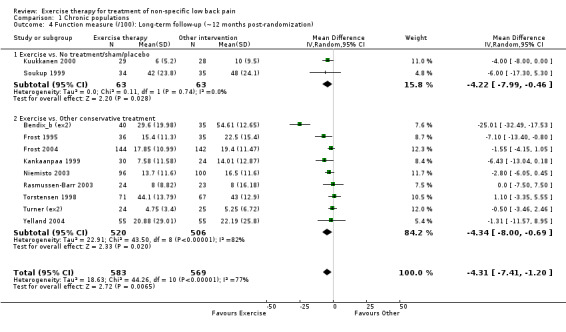

| 4 Function measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization) | 11 | 1152 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.31 [‐7.41, ‐1.20] |

| 4.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 2 | 126 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.22 [‐7.99, ‐0.46] |

| 4.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 9 | 1026 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.34 [‐6.00, ‐0.69] |

| 5 Pain measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up | 23 | 1697 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.29 [‐10.91, ‐3.67] |

| 5.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 8 | 370 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐10.20 [‐19.09, ‐1.31] |

| 5.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 15 | 1327 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.93 [‐9.65, ‐2.21] |

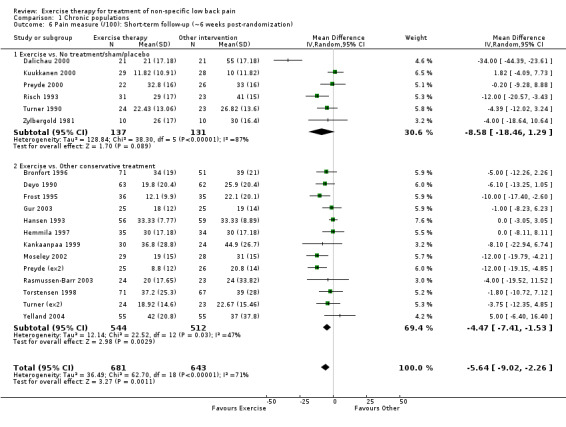

| 6 Pain measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization) | 19 | 1324 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.64 [‐9.02, ‐2.26] |

| 6.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 6 | 268 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.58 [‐18.46, 1.29] |

| 6.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 13 | 1056 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.47 [‐7.41, ‐1.53] |

| 7 Pain measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization) | 16 | 1261 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.42 [‐12.98, ‐3.86] |

| 7.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 5 | 249 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐12.48 [‐22.69, ‐2.27] |

| 7.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 11 | 1012 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐6.55 [‐11.52, ‐1.57] |

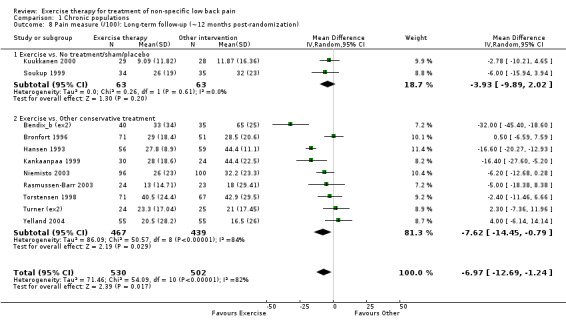

| 8 Pain measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization) | 11 | 1032 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐6.97 [‐12.69, ‐1.24] |

| 8.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 2 | 126 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.93 [‐9.89, 2.02] |

| 8.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 9 | 906 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.62 [‐14.45, ‐0.79] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Chronic populations, Outcome 1 Function measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Chronic populations, Outcome 2 Function measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Chronic populations, Outcome 3 Function measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Chronic populations, Outcome 4 Function measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Chronic populations, Outcome 5 Pain measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Chronic populations, Outcome 6 Pain measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Chronic populations, Outcome 7 Pain measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Chronic populations, Outcome 8 Pain measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization).

Comparison 2. Subacute populations.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Function measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up | 4 | 579 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.07 [‐5.32, 3.18] |

| 1.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 1 | 194 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.48 [‐9.19, 2.23] |

| 1.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 3 | 385 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.18 [‐5.99, 5.63] |

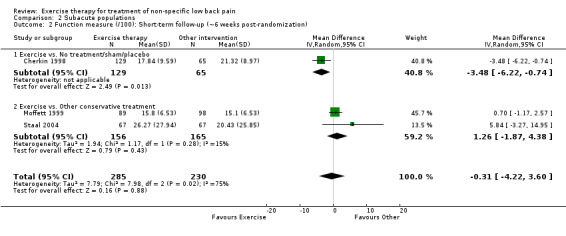

| 2 Function measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization) | 3 | 515 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.31 [‐4.22, 3.60] |

| 2.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 1 | 194 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.48 [‐6.22, ‐0.74] |

| 2.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 2 | 321 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.26 [‐1.87, 4.38] |

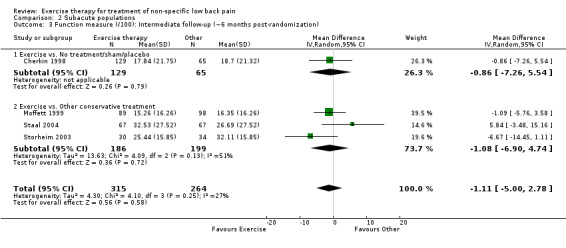

| 3 Function measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization) | 4 | 579 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.11 [‐3.00, 2.78] |

| 3.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 1 | 194 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.86 [‐7.26, 5.54] |

| 3.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 3 | 385 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.08 [‐6.90, 4.74] |

| 4 Function measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization) | 2 | 381 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.60 [‐11.34, 2.14] |

| 4.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 1 | 194 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.27 [‐13.89, ‐2.65] |

| 4.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 1 | 187 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.38 [‐5.81, 3.05] |

| 5 Pain measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up | 5 | 608 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.89 [‐4.91, 1.13] |

| 5.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 1 | 194 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.0 [‐17.25, 1.25] |

| 5.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 4 | 414 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.21 [‐4.01, 1.59] |

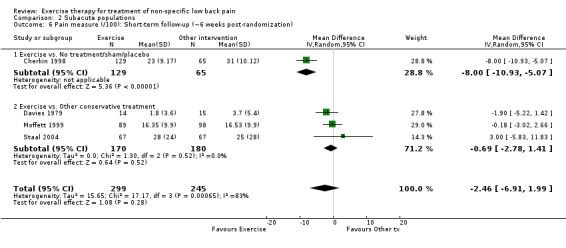

| 6 Pain measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization) | 4 | 544 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.46 [‐6.91, 1.99] |

| 6.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 1 | 194 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.0 [‐10.93, ‐5.07] |

| 6.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 3 | 350 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.69 [‐2.78, 1.41] |

| 7 Pain measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization) | 4 | 579 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.95 [‐6.48, 2.57] |

| 7.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 1 | 194 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.0 [‐14.16, 4.16] |

| 7.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 3 | 385 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.54 [‐7.36, 4.27] |

| 8 Pain measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization) | 2 | 381 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.36 [‐10.06, 1.35] |

| 8.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 1 | 194 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.0 [‐14.37, ‐1.63] |

| 8.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 1 | 187 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.03 [‐5.24, 1.18] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subacute populations, Outcome 1 Function measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subacute populations, Outcome 2 Function measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subacute populations, Outcome 3 Function measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subacute populations, Outcome 4 Function measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subacute populations, Outcome 5 Pain measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subacute populations, Outcome 6 Pain measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subacute populations, Outcome 7 Pain measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subacute populations, Outcome 8 Pain measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization).

Comparison 3. Acute populations.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up | 10 | 1097 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐1.40, 1.34] |

| 1.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 3 | 491 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.59 [‐11.51, 12.69] |

| 1.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 7 | 606 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.31 [‐0.72, 0.10] |

| 2 Pain measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization) | 10 | 1097 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐1.40, 1.34] |

| 2.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 3 | 491 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.59 [‐11.51, 12.69] |

| 2.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 7 | 606 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.31 [‐0.72, 0.10] |

| 3 Pain measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization) | 5 | 686 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.44 [‐5.11, 4.23] |

| 3.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 3 | 491 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.39 [‐9.54, 6.76] |

| 3.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 2 | 195 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.32 [‐7.79, 7.15] |

| 4 Pain measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization) | 3 | 513 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.79 [‐3.00, 3.41] |

| 4.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 1 | 318 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.82 [‐7.18, 5.54] |

| 4.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 2 | 195 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.77 [‐6.38, 4.84] |

| 5 Function measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up | 9 | 1025 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.38 [‐5.56, 2.79] |

| 5.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 3 | 491 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.82 [‐15.35, 9.71] |

| 5.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 6 | 534 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.34 [‐5.50, 2.81] |

| 6 Function measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization) | 9 | 1025 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.38 [‐5.56, 2.79] |

| 6.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 3 | 491 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.82 [‐15.35, 9.71] |

| 6.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 6 | 534 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.34 [‐5.50, 2.81] |

| 7 Function measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization) | 5 | 684 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.52 [‐0.72, 3.76] |

| 7.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 3 | 489 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.47 [‐0.26, 5.21] |

| 7.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 2 | 195 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.41 [‐4.30, 3.49] |

| 8 Function measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization) | 3 | 511 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [‐2.17, 3.31] |

| 8.1 Exercise vs. No treatment/sham/placebo | 1 | 316 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.0 [‐2.19, 6.19] |

| 8.2 Exercise vs. Other conservative treatment | 2 | 195 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.51 [‐4.13, 3.12] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acute populations, Outcome 1 Pain measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acute populations, Outcome 2 Pain measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acute populations, Outcome 3 Pain measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acute populations, Outcome 4 Pain measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acute populations, Outcome 5 Function measure (/100): Earliest follow‐up.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acute populations, Outcome 6 Function measure (/100): Short‐term follow‐up (˜6 weeks post‐randomization).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acute populations, Outcome 7 Function measure (/100): Intermediate follow‐up (˜6 months post‐randomization).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acute populations, Outcome 8 Function measure (/100): Long‐term follow‐up (˜12 months post‐randomization).

Comparison 4. POPULATION SOURCE: Chronic populations (Exploratory analysis).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Function measure (/100); Earliest follow‐up: Indirect comparisons | 21 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Health care population | 8 | 645 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐6.94 [‐11.67, ‐2.22] |

| 1.2 Occupational population | 3 | 249 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.98 [‐3.72, 1.75] |

| 1.3 General population or mixed population source | 10 | 914 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.39 [‐2.73, ‐0.05] |

| 2 Pain measure (/100); Earliest follow‐up: Indirect comparisons | 23 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Health care population (primary or secondary care) | 8 | 416 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐13.33 [‐21.13, ‐5.53] |

| 2.2 Occupational population | 4 | 282 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐9.21 [‐22.93, 4.52] |

| 2.3 General population or mixed population source | 11 | 999 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.37 [‐6.61, ‐0.13] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 POPULATION SOURCE: Chronic populations (Exploratory analysis), Outcome 1 Function measure (/100); Earliest follow‐up: Indirect comparisons.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 POPULATION SOURCE: Chronic populations (Exploratory analysis), Outcome 2 Pain measure (/100); Earliest follow‐up: Indirect comparisons.

Comparison 5. Methodological Quality of Included Studies.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 criteria met | Other data | No numeric data |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Methodological Quality of Included Studies, Outcome 1 criteria met.

| criteria met | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | randomization OK | allocation concealed | adequate follow‐up | outcome assess blind |

| Alexandre 2001 | unclear | unclear | yes | unclear |

| Aure 2003 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Bendix_a 2000 | unclear | unclear | no | no |

| Bendix_b 1995 | yes | unclear | no | no |

| Bentsen 1997 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Bronfort 1996 | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Buswell 1982 | no | unclear | no | no |

| Calmels 2004 | unclear | unclear | yes | no |

| Cherkin 1998 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Chok 1999 | yes | unclear | yes | no |

| Dalichau 2000 | unclear | unclear | yes | no |

| Davies 1979 | no | unclear | yes | yes |

| Delitto 1993 | no | unclear | unclear | no |

| Descarreaux 2002 | yes | no | yes | no |

| Deyo 1990 | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Elnaggar 1991 | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Faas 1993 | no | unclear | yes | yes |

| Farrell 1982 | no | unclear | yes | yes |

| Frost 1995 | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Frost 2004 | yes | yes | no | no |

| Galantino 2004 | yes | unclear | no | no |

| Gilbert 1985 | no | unclear | yes | no |

| Gur 2003 | unclear | unclear | yes | no |

| Hansen 1993 | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Hemmila 1997 | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Hides 1996 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Hildebrandt 2000 | yes | yes | no | no |

| Johanssen 1995 | no | unclear | no | no |

| Jousset 2004 | yes | unclear | yes | no |

| Kankaanpaa 1999 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Kendall 1968 | no | unclear | yes | no |

| Kuukkanen 2000 | unclear | unclear | yes | no |

| Lidström 1970 | no | unclear | yes | unclear |

| Lie 1999 | yes | unclear | no | yes |

| Lindstrom 1992 | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Ljunggren 1997 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Malmivaara 1995 | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Manniche 1988 | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Mannion 1999 | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Moffett 1999 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Moseley 2002 | yes | yes | no | no |

| Niemisto 2003 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Petersen 2002 | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Preyde 2000 | yes | no | yes | yes |

| Rasmussen‐Barr 2003 | unclear | unclear | no | no |

| Risch 1993 | no | no | yes | no |

| Rittweger 2002 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Seferlis 1998 | no | unclear | no | yes |

| Soukup 1999 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Staal 2004 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Stankovic 1990 | yes | yes | yes | unclear |

| Storheim 2003 | yes | yes | no | no |

| Torstensen 1998 | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Tritilanunt 2001 | yes | unclear | yes | no |

| Turner 1990 | yes | yes | no | no |

| Underwood 1998 | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Waterworth 1985 | no | no | yes | no |

| Yelland 2004 | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Yeung 2003 | unclear | yes | yes | no |

| Yozbatiran 2004 | unclear | unclear | yes | no |

| Zylbergold 1981 | no | unclear | yes | no |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Alexandre 2001.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: Methodological Quality of Included Studies for detailed information. | |

| Participants | Chronic population; Occupational; N=33 | |

| Interventions | ‡E1. Multiple components: exercise, plus home exercises; Time :24; Deliv:Group; Other:Advice to stay active/ education; C1. No treatment | |

| Outcomes | §Pain (VAS/10) | |

| Notes | See footnote for explanation of symbols, terms and abbreviations | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Aure (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Aure 2003.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Chronic population; Occupational; N=49 | |

| Interventions | E1. Stretching exercises (2/3); passive manipulation (1/3); Time:10; Deliv:Individual; independent; Other:Manual therapy; analgesics/NSAIDS; E2. Individually designed: strengthening, stretching, mobilizing, coordination, stabilizing exercises for abdominal, back, pelvic, lower limb; equipment; Time:10; Deliv:Individual; independent; Other:Analgesics/NSAIDS; | |

| Outcomes | Pain (VAS), function (Osw), RTW | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bendix_a (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Bendix_a 2000.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Chronic population; Occupational; N=138 | |

| Interventions | E1. Aerobics and strengthening (machines); Time:36; Deliv:Group; Other:None; E2. Functional restoration; comprehensive multidisciplinary approach including aerobics, strengthening, stretching; Time:36; Deliv:Group; Other:Behavioural therapy; backschool; | |

| Outcomes | Pain (NRS), function (MRS), RTW, global | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bendix_b (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Bendix_b 1995.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Chronic population; Secondary or tertiary care (referred); N=106 | |

| Interventions | E1. Functional restoration; comprehensive multidisciplinary approach including aerobics, strengthening, stretching; Time:24; Deliv:Group; Other:Behavioural therapy; backschool; E2. Aerobics and strengthening ; Time:24; Deliv:Group; Other:Backschool; C1. Other conservative | |

| Outcomes | Pain (VAS/10), function (ADL/30), RTW | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bentsen (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Bentsen 1997.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Chronic† population; General population; N=74 | |

| Interventions | E1. Dynamic strength back exercises: at gym and home; Time:21.8; Deliv:Individual; independent; Other:None; E2. Home exercises; Time:21.8; Deliv:Independent only; Other:None; | |

| Outcomes | Function (Million), RTW | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bronfort (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Bronfort 1996.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Chronic population; General population; N=103 | |

| Interventions | E1. Dynamic trunk (Manniche) and abdominal strengthening; Time:20; Deliv:Individual; Other:Manual therapy; E2. Same exercise plus NSAIDS; Time:20; Deliv:Individual; Other:Analgesics/NSAIDS; C1. Other conservative | |

| Outcomes | Pain (VAS/10), function (RMDQ) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Buswell (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Buswell 1982.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Chronic† population; Primary care; N=50 | |

| Interventions | E1. Extension exercise program (cites McKenzie); Time:11; Deliv:Individual; Other:Manual therapy; advice to stay active/ education; E2. Flexion program (mobilizing exercises plus posture); Time:11; Deliv:Individual; Other:Manual therapy; advice to stay active/ education; | |

| Outcomes | Pain (unknown measure) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Calmels (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Calmels 2004.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Chronic population; Secondary or tertiary care (referred); N=17 | |

| Interventions | E1. Isokinetic strengthening exercises (Cybex machines); Time:4.5; Deliv:Individual; Other:Manual therapy; E2. Physiotherapy exercises: series of three groups of exercises (whole body); Time:4.5; Deliv:Individual; Other:None; | |

| Outcomes | Pain (VAS), function (QDI) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Cherkin 1998.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Subacute population; Secondary or tertiary care (referred); N=321 | |

| Interventions | E1. McKenzie exercise program (trained physiotherapists, centralize symptoms); Time:7.3; Deliv:Individual; Other:Advice to stay active/ education; C1. No treatment; C2. Other conservative | |

| Outcomes | Pain (VAS/10), function (RMDQ /23), RTW | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Chok 1999.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Acute population; Secondary or tertiary care (referred); N=54 | |

| Interventions | E1. Extensor endurance program: aerobics, stretching, strengthening; Time:13.5; Deliv:Individual; Other:Advice to stay active/ education; passive modality; C1. No treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain (VAS), function (RMDQ) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dalichau (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Dalichau 2000.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Chronic population; Secondary or tertiary care (referred); N=63 | |

| Interventions | E1. Strengthening: warm up aerobic exercises, 60 min equipment training (total body); Time:12; Deliv:Individual; Other:Lumbar support; E2. Same as above with no lumbar support during exercises; Time:12; Deliv:Individual; Other:None; C1. No treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain (VAS/10), function (Osw) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Davies (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Davies 1979.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Subacute population; Primary care; N=43 | |

| Interventions | E1. Extension exercises (‘prone, raising trunk’ – described as back muscle strengthening); Time:9.6; Deliv:Individual; Other:Passive modality; E2. Flexion exercises (described as ‘mobilizing’) ; Time:9.6; Deliv:Individual; Other:Passive modality; C1. Other conservative | |

| Outcomes | Pain (VAS), RTW, global | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Delitto (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Delitto 1993.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Acute population; Secondary or tertiary care (referred); N=24 | |

| Interventions | E1. Williams flexion exercise regimen with home exercises; Time:7.3; Deliv:Individual; Other:Manual therapy; E2. McKenzie regimen plus long‐lever manipulation; Time:7.3; Deliv:Individual; Other:Manual therapy; | |

| Outcomes | Function (Osw) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Descarreaux (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Descarreaux 2002.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Chronic† population; General population; N=20 | |

| Interventions | E1. Standard stretching/ strengthening program; Time:18.3; Deliv:Independent; Other:None; E2. Force, extensibility exercises of trunk and hip muscles based on initial evaluation; targeted increased ; Time:18.3; Deliv:Independent with FU; Other:None; | |

| Outcomes | Pain (VAS), function (Osw) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Deyo 1990.

| Methods | See Comparisons and Data Table 05: | |

| Participants | Chronic population; General population; N=125 | |

| Interventions | E1. 12 sequential relaxation and stretching exercises (improve flexibility) (home exercises with repeated instruction); exercises plus TENS; Time:10.6; Deliv:Independent with FU; Other:Advice to stay active/ education; passive modality; C1. Other conservative | |

| Outcomes | Pain (VAS), function (SIP), global | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Elnaggar (ex2).

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Elnaggar 1991.