Abstract

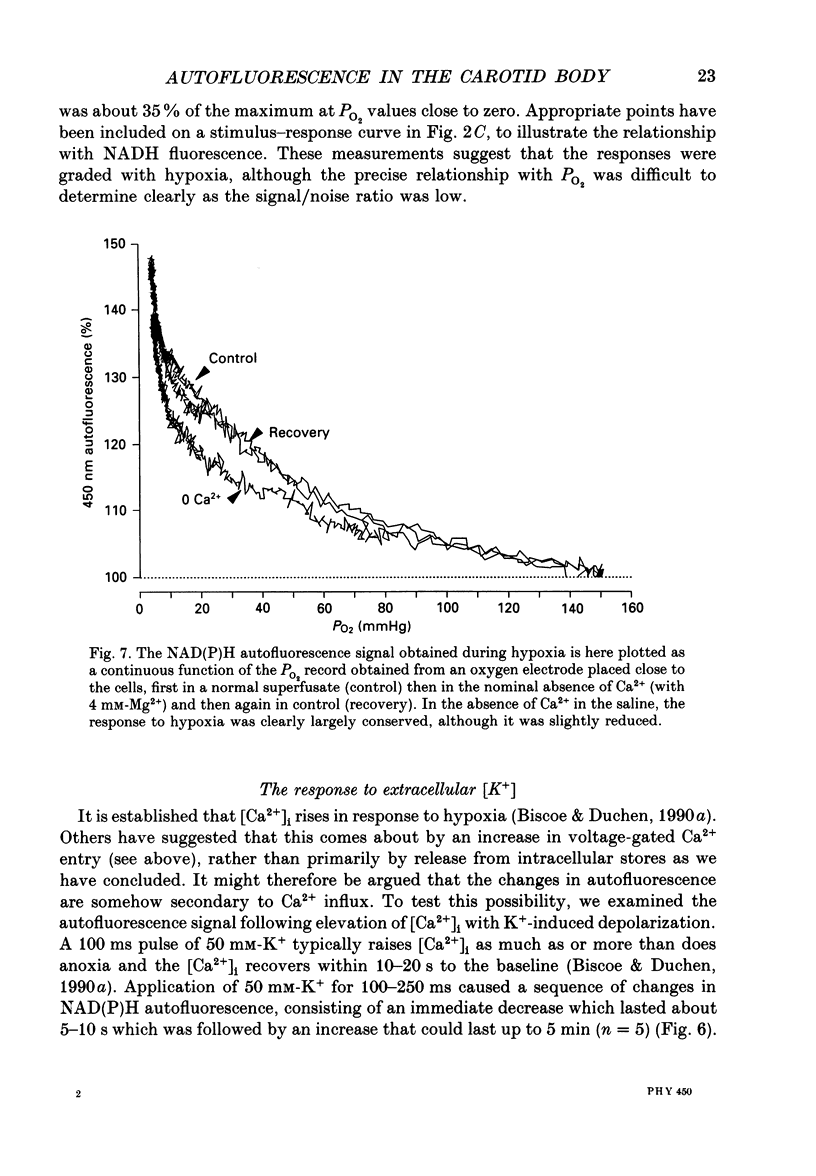

1. In this, and the accompanying paper (Duchen & Biscoe, 1992), we test the hypothesis that the oxygen sensitivity of mitochondrial electron transport forms a basis for transduction in the carotid body, the primary peripheral arterial oxygen sensor. We here describe for isolated type I cells the changes in autofluorescence of mitochondrial NAD(P)H that accompany changes in PO2. 2. NAD(P)H autofluorescence (excitation, 340-360 nm; emission peak, 450 nm) increased with anoxia, reflecting a rise in the NAD(P)H/NAD(P) ratio. Graded increases in autofluorescence were seen in response to graded decreases in PO2, suggesting that mitochondrial function is progressively altered below a PO2 of about 60 mmHg. 3. A mitochondrial origin for the NAD(P)H autofluorescence was suggested by the mutual exclusion of the responses to anoxia and cyanide. 4. Oxidized flavoproteins fluoresce when excited at 450 nm with an emission peak at 550 nm. The small signals obtained under these conditions increased with uncoupler and showed a graded decrease with falling PO2 reflecting a rise in the FADH/FAD ratio. 5. Hypoxia raises [Ca2+]i. The hypoxia-induced changes in mitochondrial function were not secondary to this rise. A brief K(+)-induced depolarization leads to a transient increase in [Ca2+]i. At the same time there is a rapid decrease in NAD(P)H autofluorescence followed by an increase that far outlasts the rise in [Ca2+]i. This delayed increase in autofluorescence was smaller than was the increase with anoxia, even though K(+)-induced depolarization raised [Ca2+]i more than does anoxia. In Ca(2+)-free solutions the depolarization-induced changes were abolished, while those associated with hypoxia were maintained. 6. The changes of autofluorescence with K(+)-induced depolarization appear to reflect (i) oxidation of NAD(P)H by stimulation of respiration following mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and (ii) reduction of NAD(P) by the Ca(2+)-dependent activation of mitochondrial dehydrogenases. This activation could last several minutes following only 100 ms depolarization, while the changes accompanying hypoxia closely followed the time course of the change in PO2. 7. In similarly isolated rat or mouse chromaffin cells and mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons under identical conditions, no measurable change in autofluorescence or in [Ca2+]i was seen until the PO2 fell below about 5 mmHg. 8. Carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone (FCCP) increases O2 consumption, oxidizing mitochondrial NADH and hence decreasing autofluorescence, (delta FFCCP). Blockade of electron transport by anoxia or CN- decreases O2 consumption, increasing mitochondrial NADH/NAD and autofluorescence (delta FCN). The fractional change in autofluorescence with FCCP, delta FFCCP/delta FFCCP+FCN), is thus a measure of resting O2 consumption.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Acker H., Dufau E., Huber J., Sylvester D. Indications to an NADPH oxidase as a possible pO2 sensor in the rat carotid body. FEBS Lett. 1989 Oct 9;256(1-2):75–78. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81721-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscoe T. J. Carotid body: structure and function. Physiol Rev. 1971 Jul;51(3):437–495. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1971.51.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscoe T. J., Duchen M. R. Cellular basis of transduction in carotid chemoreceptors. Am J Physiol. 1990 Jun;258(6 Pt 1):L271–L278. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1990.258.6.L271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscoe T. J., Duchen M. R. Responses of type I cells dissociated from the rabbit carotid body to hypoxia. J Physiol. 1990 Sep;428:39–59. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscoe T. J., Purves M. J. Observations on the rhythmic variation in the cat carotid body chemoreceptor activity which has the same period as respiration. J Physiol. 1967 Jun;190(3):389–412. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveris A., Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J. 1973 Jul;134(3):707–716. doi: 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. C., Lakin-Thomas P. L., Brand M. D. Control of respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in isolated rat liver cells. Eur J Biochem. 1990 Sep 11;192(2):355–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANCE B., BALTSCHEFFSKY H. Respiratory enzymes in oxidative phosphorylation. VII. Binding of intramitochondrial reduced pyridine nucleotide. J Biol Chem. 1958 Sep;233(3):736–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANCE B., WILLIAMS G. R. The respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation. Adv Enzymol Relat Subj Biochem. 1956;17:65–134. doi: 10.1002/9780470122624.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROSS B. A., SILVER I. A. Some factors affecting oxygen tension in the brain and other organs. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1962 Nov 20;156:483–499. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1962.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B., Schoener B., Oshino R., Itshak F., Nakase Y. Oxidation-reduction ratio studies of mitochondria in freeze-trapped samples. NADH and flavoprotein fluorescence signals. J Biol Chem. 1979 Jun 10;254(11):4764–4771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross A. R., Henderson L., Jones O. T., Delpiano M. A., Hentschel J., Acker H. Involvement of an NAD(P)H oxidase as a pO2 sensor protein in the rat carotid body. Biochem J. 1990 Dec 15;272(3):743–747. doi: 10.1042/bj2720743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE BURGH DALY M., LAMBERTSEN C. J., SCHWEITZER A. Observations on the volume of blood flow and oxygen utilization of the carotid body in the cat. J Physiol. 1954 Jul 28;125(1):67–89. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpiano M. A., Hescheler J. Evidence for a PO2-sensitive K+ channel in the type-I cell of the rabbit carotid body. FEBS Lett. 1989 Jun 5;249(2):195–198. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80623-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen M. R., Biscoe T. J. Relative mitochondrial membrane potential and [Ca2+]i in type I cells isolated from the rabbit carotid body. J Physiol. 1992 May;450:33–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen M. R., Caddy K. W., Kirby G. C., Patterson D. L., Ponte J., Biscoe T. J. Biophysical studies of the cellular elements of the rabbit carotid body. Neuroscience. 1988 Jul;26(1):291–311. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen M. R. Effects of metabolic inhibition on the membrane properties of isolated mouse primary sensory neurones. J Physiol. 1990 May;424:387–409. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. W., Hallett M. B., Lloyd D., Campbell A. K. Decrease in apparent Km for oxygen after stimulation of respiration of rat polymorphonuclear leukocytes. FEBS Lett. 1983 Sep 5;161(1):60–64. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80730-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emaus R. K., Grunwald R., Lemasters J. J. Rhodamine 123 as a probe of transmembrane potential in isolated rat-liver mitochondria: spectral and metabolic properties. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986 Jul 23;850(3):436–448. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(86)90112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng J., Lynch R. M., Balaban R. S. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide fluorescence spectroscopy and imaging of isolated cardiac myocytes. Biophys J. 1989 Apr;55(4):621–630. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82859-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erecińska M., Wilson D. F. Regulation of cellular energy metabolism. J Membr Biol. 1982;70(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF01871584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganfornina M. D., López-Barneo J. Single K+ channels in membrane patches of arterial chemoreceptor cells are modulated by O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Apr 1;88(7):2927–2930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatley S. J., Sherratt S. A. The effects of diphenyleneiodonium on mitochondrial reactions. Relation of binding of diphenylene[125I]iodonium to mitochondria to the extent of inhibition of oxygen uptake. Biochem J. 1976 Aug 15;158(2):307–315. doi: 10.1042/bj1580307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansford R. G. Relation between mitochondrial calcium transport and control of energy metabolism. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1985;102:1–72. doi: 10.1007/BFb0034084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek J. B., Rydström J. Physiological roles of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase. Biochem J. 1988 Aug 15;254(1):1–10. doi: 10.1042/bj2540001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. P. Effect of mitochondrial clustering on O2 supply in hepatocytes. Am J Physiol. 1984 Jul;247(1 Pt 1):C83–C89. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1984.247.1.C83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson S. N., Biscoe T. J. Electrophysiological observations on immature rat nerve cells grown in tissue culture. J Cell Physiol. 1973 Oct;82(2):285–297. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040820217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-López J., González C., Ureña J., López-Barneo J. Low pO2 selectively inhibits K channel activity in chemoreceptor cells of the mammalian carotid body. J Gen Physiol. 1989 May;93(5):1001–1015. doi: 10.1085/jgp.93.5.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack J. G., Denton R. M. Role of Ca2+ ions in the regulation of intramitochondrial metabolism in rat heart. Evidence from studies with isolated mitochondria that adrenaline activates the pyruvate dehydrogenase and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complexes by increasing the intramitochondrial concentration of Ca2+. Biochem J. 1984 Feb 15;218(1):235–247. doi: 10.1042/bj2180235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills E., Jöbsis F. F. Mitochondrial respiratory chain of carotid body and chemoreceptor response to changes in oxygen tension. J Neurophysiol. 1972 Jul;35(4):405–428. doi: 10.1152/jn.1972.35.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills E., Jöbsis F. F. Simultaneous measurement of cytochrome a3 reduction and chemoreceptor afferent activity in the carotid body. Nature. 1970 Mar 21;225(5238):1147–1149. doi: 10.1038/2251147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan E., Lahiri S., Storey B. T. Carotid body O2 chemoreception and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1981 Aug;51(2):438–446. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.51.2.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair P. K., Buerk D. G., Whalen W. J. Cat carotid body oxygen metabolism and chemoreception described by a two-cytochrome model. Am J Physiol. 1986 Feb;250(2 Pt 2):H202–H207. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.2.H202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair P., Whalen W. J., Buerk D. PO2 of cat cerebral cortex: response to breathing N2 and 100 per cent O21. Microvasc Res. 1975 Mar;9(2):158–165. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(75)90077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peers C. Hypoxic suppression of K+ currents in type I carotid body cells: selective effect on the Ca2(+)-activated K+ current. Neurosci Lett. 1990 Nov 13;119(2):253–256. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SBARRA A. J., KARNOVSKY M. L. The biochemical basis of phagocytosis. I. Metabolic changes during the ingestion of particles by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1959 Jun;234(6):1355–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver I. A. Some observations on the cerebral cortex with an ultramicro, membrane-covered, oxygen electrode. Med Electron Biol Eng. 1965 Oct;3(4):377–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02476132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea A., Nurse C. A. Whole-cell and perforated-patch recordings from O2-sensitive rat carotid body cells grown in short- and long-term culture. Pflugers Arch. 1991 Mar;418(1-2):93–101. doi: 10.1007/BF00370457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. F., Erecińska M. The oxygen dependence of cellular energy metabolism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1986;194:229–239. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5107-8_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]