Abstract

SUMMARY

Conclusions regarding the contribution of low molecular weight secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) enzymes in eicosanoid generation have relied on data obtained from transfected cells or the use of inhibitors that fail to discriminate between individual members of the large family of mammalian sPLA2 enzymes. To elucidate the role of group V sPLA2, we used targeted gene disruption to generate mice lacking this enzyme. Zymosan-induced generation of leukotriene C4 and prostaglandin E2 was attenuated ~50% in peritoneal macrophages from group V sPLA2-null mice compared to macrophages from wild-type littermates. Furthermore, the early phase of plasma exudation in response to intraperitoneal injection of zymosan and the accompanying in vivo generation of cysteinyl leukotrienes were markedly attenuated in group V sPLA2-null mice compared to wild-type controls. These data provide clear evidence of a role for group V sPLA2 in regulating eicosanoid generation in response to an acute innate stimulus of the immune response both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting a role for this enzyme in innate immunity.

INTRODUCTION

The first step in the biosynthesis of eicosanoids is the release of arachidonic acid from cell membrane phospholipids by phospholipase A2 (PLA2). Several classes of PLA2 have been described in mammals (1;2). Cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2) α is an 85-kDa cytosolic enzyme that uses a catalytic serine residue and preferentially cleaves arachidonic acid from cell membrane phospholipids (3). The Ca2+-dependent translocation of cPLA2α from the cytosol to the nuclear envelope (4), a prominent site of eicosanoid biosynthesis, is dependent on a Ca2+-dependent lipid binding (C2) domain. Paralogues of cPLA2α (cPLA2β and cPLA2γ) have been described (5;6). cPLA2β has a Mr of 110,000 and shares 30% identity with cPLA2α, including a functional C-2 domain. cPLA2γ has a Mr of 61,000, shares 29% sequence identity with cPLA2α, lacks a C-2 domain, and is Ca2+-independent. Mammalian low molecular weight secretory PLA2 (sPLA2) enzymes, which are now 10 in number, are characterized by a conserved motif containing a catalytic histidine residue, by their relatively small size of ~14 kDa, and by their highly disulfide-linked tertiary structures (1;7). They are distinguished from one another by their structure, their biochemical properties, and their tissue distribution. Calcium-independent PLA2 enzymes have been described in myocardium and in leukocytes (8;9). They have been implicated in membrane remodeling, regulation of store operated calcium channels , apoptosis, and release of arachidonic acid. The fourth group of PLA2 enzymes comprises the acetyl hydrolases of platelet activating factor (10).

Given the complexity and size of the PLA2 family, targeted gene disruption is a suitable approach to elucidating the role(s) of individual enzymes and proved fruitful in determining to role of cPLA2α in regulating eicosanoid biosynthesis. Disruption of the gene encoding cPLA2α led to almost complete abrogation of the rapid generation of prostaglandin (PG) E2, leukotriene (LT) C4, and LTB4 from peritoneal macrophages in response to A23187 and of the more delayed generation of PGE2 in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (11;12). Separate studies demonstrated a marked attenuation of the release of labeled arachidonic acid from cPLA2-α -null peritoneal macrophages in response to zymosan, A23187, phorbol myristate acetate, and okadaic acid (13), and the critical role of this enzyme in immediate and delayed phases of eicosanoid generation by mouse bone marrow culture-derived mast cells (14;15).

While these data demonstrate the essential function of cPLA2-α in supplying arachidonic acid for leukotriene and prostaglandin biosynthesis, several lines of evidence have suggested that low molecular weight sPLA2 enzymes amplify the actions of cPLA2-α in eicosanoid generation. Transfection of HEK 293 cells with the heparin-binding group IIA sPLA2, group V sPLA2, or group IID sPLA2 amplified the cPLA2-α -dependent release of arachidonic acid and PGE2 generation in response to A23187 or to LPS and IL-1β (16;17). The action of these enzymes was attributed to their ability to bind to glypican in caveoli, leading to internalization and co-localization with prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase (PGHS) enzymes (16). Similarly, adenoviral transfection of group V sPLA2 or group IIA sPLA2 into mouse mesangial cells amplified H2O2-induced release of arachidonic acid. This was observed only in cPLA2-α sufficient and not in cPLA2-α -null cells (18). When P388D1 macrophages were primed with LPS for one hour and then activated with platelet activating factor, there was biphasic release of labeled arachidonic acid (19). Studies with pharmacologic inhibitors and with antisense oligonucleotides suggested that the initial intracellular release of arachidonic acid was dependent upon cPLA2-α, whereas the subsequent extracellular release was dependent upon group V sPLA2 that was dependent upon the initial action of cPLA2-α (20;21). In certain subclones of the P388D1 macrophage, LPS stimulation alone elicited a delayed phase of arachidonic acid release and PGHS-2-dependent PGE2 generation. Both cPLA2-α and group V sPLA2 were required, but, in contrast to the primed-immediate response to LPS and platelet activating factor, activation of cPLA2-α led to induction of group V sPLA2 expression that in turn induced PGHS-2 (22).

The data implicating low molecular weight sPLA2 enzymes in eicosanoid generation have thus relied on either transfection experiments or upon pharmacological and antisense inhibition experiments. The former, while informative as to the potential functions of a sPLA2, fail to address the role of the endogenous enzymes. The latter have lacked specificity (19;21), failed to discriminate between individual low molecular weight PLA2 enzymes (23), or have yielded conflicting data (24;25). To definitively test the role of group V sPLA2 in vivo and in vitro we have generated mice with targeted disruption of its gene.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Restriction enzymes were from Roche, Mannheim, Germany. Human serum albumin, zymosan A, Evans blue dye, paraformaldehyde were from Sigma, St, Louis, MO.

Targeted disruption of the gene for group V sPLA2 -

We used a group V sPLA2 cDNA (26) to screen a 129 mouse genomic DNA library in Lambda FIX II (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). An ~11 kb portion of the group V sPLA2 gene, composed of two contiguous Sac I restriction fragments, was isolated and was used to construct a targeting vector in pBluescript (Fig. 1A) in which the fourth exon was excised with Bcl I and replaced with a neomycin resistance gene that lacked a polyadenylylation signal. This leads to loss of the histidine residue essential for the catalytic function of the sPLA2 enzymes (27) and will lead to a premature stop codon if exons III and V are spliced. A thymidine kinase gene was inserted at a Sal I site within pBluescript upstream of the Bam HI site.

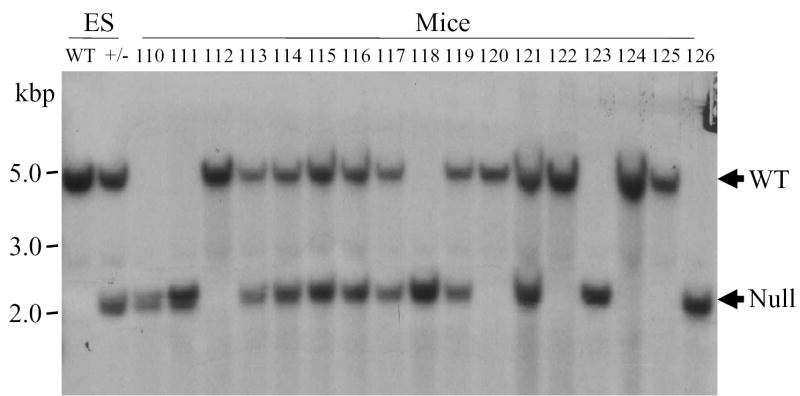

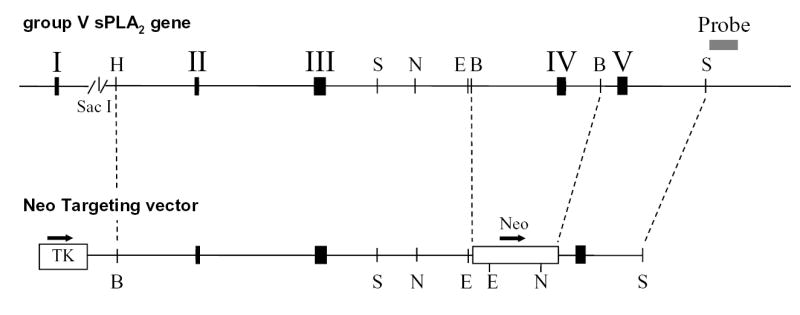

Figure 1. Targeted disruption of the gene encoding group V sPLA2.

A. Schematic diagram of the group V sPLA2 gene and the targeting vector. The black solid boxes with roman numerals denote exons. Arrows show the orientation of the thymidine kinase gene (TK), and the neomycin (Neo) resistance gene. Relevant restriction enzyme sites are indicated; H, Bam HI; S, Sac I; N, Nco I; E, Eco RI; B, Bcl I. The gray box represents the probe used in Southern blotting. B. Genomic Southern blotting of mouse tail DNA. Numbers designate DNA from individual mice. DNA from wild-type (WT) 129 embryonic stem (ES) cells and from 129 ES cells transfected with the neomycin-resistance targeting vector(+/−) served as controls. kbp, kilobase pairs. Arrows indicate the migration of WT and null alleles. C. RNA blot analysis of hearts from the hearts of mice genotyped in Figure 1B. Kb, kilobases. D. RT-PCR analysis of heart RNA from the same mice. S, DNA ladder

Embryonic stem cells were transfected with the linearized targeting construct. Clones with homologous recombination of the targeting vector were selected in gancyclovir and neomycin according to established protocols and were identified by genomic Southern blotting. Two 129 embryonic stem cell clones, heterozygous for disruption of the group V sPLA2 gene were injected separately into blastocysts from C57BL/6 mice and transferred to the uteri of C57BL/6 pseudopregnant females. Pups that were chimeric for 129 and C57BL/6 cells were detected by coat color. Five mice, three males and two females, with >50% chimerism were obtained. Two of the males, each derived from different ES cell clones, were bred back to C57BL/6 mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Offspring were screened for transmission of the disrupted allele of group V sPLA2 by Southern blotting of DNA derived from tail snips. Breeding pairs from this F1 generation of group V sPLA2 +/− mice were established and their F2 group V sPLA2-null and group V sPLA2-wild type progeny were used in subsequent experiments.

Southern blotting

DNA, extracted from mouse tail snips was digested with Nco I or Eco RI, resolved in separate lanes of 1 % agarose gels, transferred to Immobilon NY membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and probed with a [32P]dCTP random prime-labeled (Stratagene) 306 base-pair portion of DNA from the 3′ untranslated region of the group V sPLA2 gene that lies outside the targeting construct (Fig. 1A).

Northern Blotting

Mouse hearts were homogenized in Tri Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, Ohio) and RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 10 μg of RNA from each heart were resolved in separate lanes of 1.2% agarose formaldehyde gels, blotted to Immobilon-N (Millipore), and probed with a [32P]dCTP-labeled cDNA spanning the open reading frame of group V sPLA2 as described (28).

RT-PCR

Expression of transcripts for group V sPLA2 was also analyzed by RT-PCR. 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using MMLV reverse transcriptase and the Advantage RT for PCR kit (Clontech, La Jolla, CA) for 1 h at 42°C. 5 μl of the resulting reaction mixture was used in a PCR reaction with Taq Gold polymerase (Perkin Elmer, Torrance, CA), using the following primers that span the open-reading frame: forward - 5′ACACTGGCTTGGTTCCTGGC3′ in exon II, and reverse - 5′GACATTAGCAGAGAAGTTGGGG3′ in exon V. PCR conditions were a denaturing step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 45 sec, 65°C for 45 sec, and 72°C for 90 sec, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. Primers for S15 ribosomal protein (Ambion, Austin, TX) were used as a positive control. Products were resolved on 2% agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide.

Immunofluorescence analysis of group V sPLA2 expression

The peritoneal cavities of mice were flushed with 5 ml of ice-cold PCG buffer (25 mM Pipes, 110 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1mM CaCl2, 1 g/L glucose, pH 7.4). After washing, 3.3x105 cells were plated on glass cover slips in 24-well tissue culture plates in 500 μl of PCG buffer, 10 % FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and incubated overnight at 37ºC with 5% CO2. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing three times with PCG buffer. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min at room temperature, washed once in Hanks’ balanced salt solution without Mg2+ or Ca2+ (HBSS–) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (HBA), permeabilized with 0.025% saponin (Sigma) in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, and washed twice with HBA. Macrophages were then blocked in HBA containing 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml rabbit anti-mouse group V PLA2 (26) in blocking buffer for 2 h at room temperature, washed extensively with HBA, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (heavy and light chains, Jackson ImmunoResearch), diluted 1:400. Cells were washed five times with HBA, mounted in Vectashield™ mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and imaged with a Nikon Eclipse TE2000U microscope coupled with a Spot-RT Digital Camera.

Isolation and activation of mouse peritoneal macrophages

The peritoneal cavities of mice, sacrificed by CO2 inhalation, were flushed with 5 ml of ice-cold Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Life Sciences, Rockville, MD) containing 10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 U/ml heparin. After two washes in HBSS–, 3.75 x 105 cells in 500 μl DMEM,10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin were placed in individual wells of a 48-well tissue culture plate and were incubated for 3 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing with HBSS–. Non-adherent cells from each mouse were pooled and counted to determine the fraction of adherent cells, which was not different between group V sPLA2-null cells and wild-type cells. 200 μl of DMEM containing 0.1% human serum albumin were added to each well, and adherent cells were stimulated in a dose and time-dependent manner with zymosan A (29) (0 to 100 particles per cell; 0 to 6 h). Supernatants were collected for measurements of cysteinyl leukotrienes and PGE2 by enzyme-linked immunoassays (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). In some experiments supernatants were analyzed for cysteinyl leukotriene content by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC).

Zymosan-induced peritonitis

Each mouse received an injection of 0.5% Evans blue dye in PBS into the tail vein (100 μg of dye per gram of body weight) immediately before injection of 1 ml of zymosan A (1 mg/ml in PBS) into the peritoneal cavity (30). At selected times, up to 2 h later, the mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and the peritoneal cavity was lavaged with 4 ml of ice-cold PBS. The peritoneal lavage fluid was centrifuged at 500 x g for 5 min and the optical density of the supernatant was measured at 610 nm to assess extravasation of Evans blue dye. In some experiments 4 volumes of ethanol and 60 ng of PGB2 (as internal standard for RP-HPLC) were added to the lavage fluid, mixed well, incubated on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were then dried by vacuum centrifugation, resuspended in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, methanol: 1:2 w/v and analyzed for cysteinyl leukotriene content by RP-HPLC.

RP-HPLC analysis of cysteinyl leukotrienes

Cysteinyl leukotrienes were measured by RP-HPLC as described (30;31). Briefly, samples were applied to a 5 μm, 4.6 x 250 mm C18, Ultrasphere RP column (Beckman, Palo Alto, CA) equilibrated with a solvent of methanol/acetonitrile/water/acetic acid (10:15:100:0.2, v/v), pH 6.0 (solvent A). After injection of the sample, the column was eluted at a flow rate of 1 ml/min with a programmed concave gradient to 55% of solvent A and 45% methanol over 2.5 min. After 5 min, methanol was increased linearly to 75% over 15 min and was maintained at this level for an additional 15 min. The UV absorbance at 280 nM was recorded. The retention times for PGB2, LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4 were 21.4, 22.2, 23.7, and 25.1 min, respectively. Quantities of cysteinyl leukotrienes were calculated from the ratio of the peak area of each leukotriene to the peak area of the PGB2 internal standard after correction for the differences in molar extinction coefficients.

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as arithmetic means and standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical differences between groups were calculated using Student’s t test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Generation of mice lacking group V sPLA2

To generate mice lacking group V sPLA2 we used targeted gene disruption. Southern blotting of wild-type genomic DNA for group V sPLA2 yielded bands of ~5 kb and ~3.7 kb with Nco I (Fig. 1B) and Eco RI (not shown) digestion, respectively. Southern blotting of DNA from animals with disruption of the group V sPLA2 gene yielded bands 2.6 kb and 0.8 kb smaller than wild-type DNA with Nco I (Fig. 1B) and Eco RI digestion (data not shown), respectively, as predicted from restriction enzyme mapping of wild-type and mutated alleles (Fig. 1A). The mouse heart is rich in transcripts for group V sPLA2 (32). To confirm that incorporation of the disrupted allele for group V sPLA2 led to loss of normal transcripts, RNA was extracted from the hearts of mice born to the F1 intercrosses and analyzed for group V sPLA2 transcripts by RNA blotting (Fig. 1C) and RT-PCR (Fig. 1D). RNA from hearts of wild-type mice and BALB/c mice yielded a band of ~2 kb on Northern analysis (Fig. 1C) whereas RNA from mice genotyped as having no wild-type allele for the group V sPLA2 gene yielded only aberrant transcripts of ~ 4kb and lacked a transcript of the appropriate size on Northern analysis (Fig. 1C). That the aberrant transcripts observed in group V sPLA2-null hearts were non-productive is revealed by RT-PCR. RT-PCR analysis of wild-type hearts yielded a product of the expected size (~400 bp) and also a smaller product that on sequencing was shown to lack exon IV, indicative of alternate splicing, as previously described for group V sPLA2 (33). RT-PCR analysis of RNA from group V sPLA2-null hearts failed to yield a product in RT-PCR (Fig. 1D).

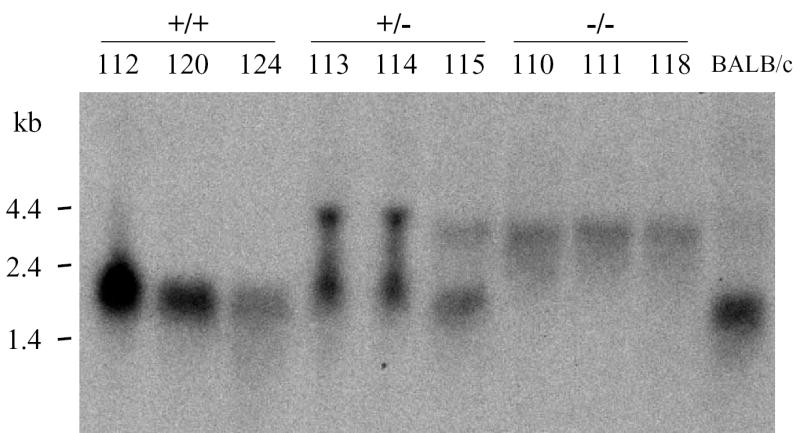

Immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 2) confirmed the lack of expression of group V sPLA2 in peritoneal macrophages from group V sPLA2-null mice. By comparison, peritoneal macrophages from wild-type littermates revealed cytoplasmic staining for group V sPLA2 with perinuclear accentuation, similar to the pattern we previously reported for mouse BMMC (26).

Figure 2. Immunofluorescence staining for group V sPLA2.

Peritoneal macrophages from group V sPLA2 wild-type (A) and group V sPLA2-null (B) mice were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.025% saponin, and stained with affinity purified rabbit IgG anti-mouse group V sPLA2, followed by FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG. Nuclei were stained blue with Hoechst stain.

Breeding of mice heterozygous for the disrupted allele of group V sPLA2 produced approximately equal numbers of male and female mice with a Mendelian pattern of inheritance of the disrupted allele. Group V sPLA2-null mice were healthy to at least 6 months of age, indicating that group V sPLA2 is not required for normal growth and development of mice.

Peritoneal macrophages have been used extensively to study eicosanoid generation (11–13;34), and they express group V sPLA2 (Fig. 2). As phagocytes, they are an integral part of the innate immune response. They respond to ingestion of zymosan particles, extracted from yeast, with robust eicosanoid generation in vitro (35–37), and in vivo administration of zymosan to the peritoneal cavity elicits an inflammatory response with plasma exudation that is in part dependant on the release of cysteinyl leukotrienes acting through the cysteinyl leukotriene type 1 receptor (CysLT1R) (30;38). We therefore studied eicosanoid generation in peritoneal macrophages from group V sPLA2-null mice in vitro and cysteinyl leukotriene generation and plasma extravasation in response to intraperitoneal injection of zymosan in vivo.

Zymosan-induced eicosanoid generation by mouse peritoneal macrophages

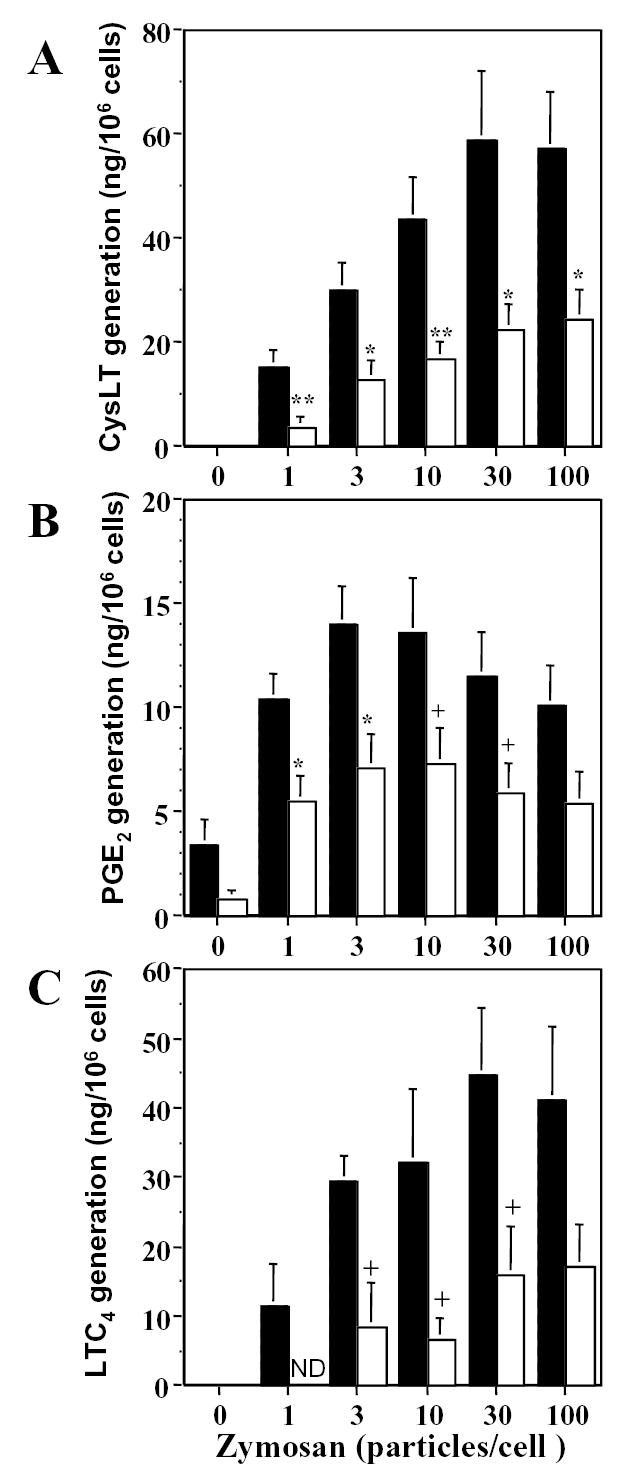

Stimulation of group V sPLA2-null and wild-type macrophages with unopsonized zymosan particles elicited maximum cysteinyl leukotriene and PGE2 generation at 3 h (Data not shown). Cysteinyl leukotriene generation plateaued at 30 to 100 zymosan particles per cell, whereas PGE2 generation plateaued with a maximal response at 3 to 10 particles per cell (figure 3, A & B). Both cysteinyl leukotriene and PGE2 generation were attenuated at all doses of zymosan in group V sPLA2-null peritoneal macrophages compared to wild-type control cells with no change in the position of the dose-response curves (Fig. 3, A & B). Cysteinyl leukotriene generation in response to 100 zymosan particles per cell was attenuated 58% in group V sPLA2-null macrophages (24.6 ± 5.7 ng/106 cells compared to 57.4 ± 10.7 ng/106 wild-type cells, n=9, p=0.01). PGE2 generation in response to 3 zymosan particles per cell was attenuated 49% in group V sPLA2-null macrophages (7.1 ± 1.6 ng/106 cells compared to 14.1 ± 1.8 ng/106 wild-type cells, n=9, p=0.01). Reverse phase HPLC analysis revealed the identity of the cysteinyl leukotrienes in the cell supernatants as LTC4 with no detectable extracellular conversion to LTD4 or LTE4 (data not shown) and confirmed the attenuation of LTC4 generation in group V sPLA2-null macrophages compared to wild-type macrophages (Fig. 3C). Attenuation of eicosanoid generation in zymosan-stimulated group V sPLA2-null peritoneal macrophages was demonstrated for macrophages obtained from mice derived from two separate ES cell clones.

Figure 3. Eicosanoid generation by peritoneal macrophages in response to zymosan particles in vitro.

Peritoneal macrophages from group V sPLA2-null (open bars) and wild-type control mice (shaded bars) were stimulated for 3 h in a dose-dependent manner. Supernatants were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunoassays for cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLT) (A) and for PGE2 (B) (n = 9), and were analyzed for CysLT generation by RP-HPLC (C) (n=6). ND, not detected. + p<0.05, * p<0.02, ** p<0.01

The role of group V sPLA2 in eicosanoid generation by zymosan-stimulated peritoneal macrophages was not predicted by prior studies. Indeed, there was complete abrogation of the release of arachidonic acid in response to zymosan in peritoneal macrophages derived from mice lacking cPLA2α (13). Combined with our data, this suggests an absolute requirement for cPLA2α in eicosanoid generation by zymosan-stimulated peritoneal macrophages and an amplifying role for group V sPLA2. This is consistent with the conclusions obtained in other cells. In HEK293 cells the function of transfected group V sPLA2 in supplying arachidonic acid for eicosanoid generation was abolished by pharmacological inhibition of cPLA2α (16). In primary cultures of mouse mesangial cells adenoviral transfection with group V sPLA2 augmented arachidonic acid release in response to H2O2 by cells obtained from cPLA2α -sufficient mice but not from cPLA2α -null mice (18). The precise mechanism by which group V sPLA2 amplifies the essential function of cPLA2α is unknown and is the subject of ongoing experiments.

Our findings were also not predicted by studies in the mouse P388D1 macrophage, in which zymosan-induced release of arachidonic acid was inhibited by methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP), an inhibitor of cPLA2α, and not by LY311717, an inhibitor of group V sPLA2 (39). The discrepancies between our data and that obtained with the P388D1 cell line may be due to the transformed nature of P388D1 cells, may relate to the observation that release of arachidonic acid in response to zymosan was only observed in the MAB clone of this cell line (39), and/or to the observation that these cells have low levels of esterified arachidonic acid compared to primary cultures of mouse macrophages (40).

Zymosan-induced peritonitis

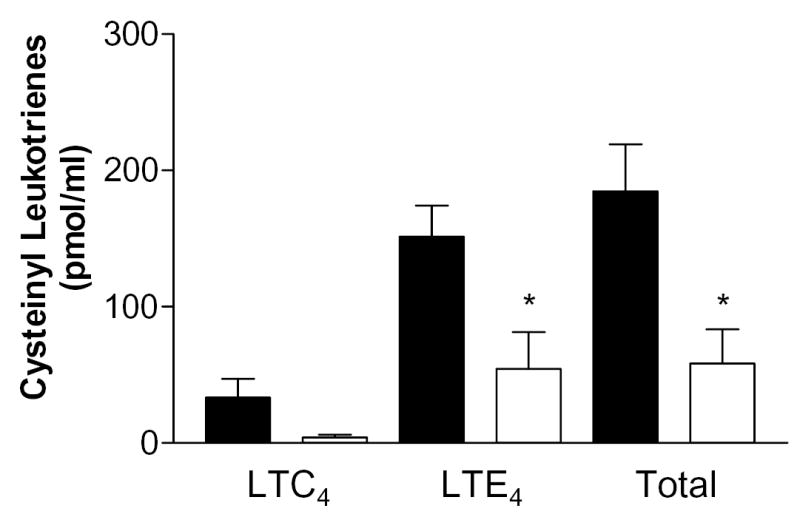

Disruption of the genes encoding LTC4 synthase (38) and of CysLT1R (30), revealed the contribution of the cysteinyl leukotrienes, acting through CysLT1R, to plasma exudation in zymosan-induced peritonitis. We therefore assessed cysteinyl leukotriene generation (by reverse phase HPLC) and plasma exudation (by leak of Evans blue dye) in group V sPLA2-null and wild type mice in response to intraperitoneal injection of a suspension of zymosan A. There was a significant ~50% attenuation of the leak of Evans blue dye 15 and 30 min after injection of zymosan in mice lacking group V sPLA2 compared to that observed in wild-type littermates (Fig. 4). No difference in plasma exudation was apparent at 60 and 120 min. We measured cysteinyl leukotrienes in the peritoneal lavage fluid 30 min after intraperitoneal injection of zymosan when there was significant attenuation of plasma extravasation. LTE4 was the predominant cysteinyl leukotriene present in the lavage fluid, as previously reported (38), and its generation was attenuated in group V sPLA2-null animals compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Plasma exudation is response to intraperitoneal injection of zymosan A.

Group V sPLA2-null (open symbols) and wild type (closed symbols) mice were injected with 1 mg/ml zymosan A and plasma exudation was assessed by the leak of Evans blue dye as described in the Experimental Procedures. Data is reported as absorbance of the peritoneal exudates at 610 nm for individual mice (A) and as the means ± SEM for each group of mice (B). * p<0.005

Figure 5. Leukotriene generation in the peritoneal exudates of mice injected with zymosan A.

Group V sPLA2-null (open symbols, n = 3) and wild type (closed symbols, n = 4) mice were injected with 1 mg/ml zymosan A. The cysteinyl leukotriene content of the exudate was measured by RP-HPLC as described in the Experimental Procedures. Data is provided separately for LTC4, LTE4, and total cysteinyl leuktoriene generation. No LTD4 was detected. * p<0.05

The attenuation of enhanced vascular permeability in response to zymosan A in group V sPLA2-null mice at early but not at later time points is somewhat distinct from the findings in mice lacking LTC4 synthase or CysLT1R (30;38). In the former, attenuated vascular permeability was observed up to one hour after intraperitoneal injection of zymosan, and in the latter it extended to 4 h. Nevertheless, the greatest attenuation of plasma exudation in both strains of mice was observed at early time points and was less marked at 2 h and 4 h, consistent with our findings in group V sPLA2-null mice and indicating a significant role for other vasoactive mediators as would be expected. Further, the attenuation of cysteinyl leukotriene generation in group V sPLA2-null mice in vivo, as in vitro, was partial allowing significant occupancy of CysLT1R as cysteinyl leukotriene generation proceeded, even in the face of attenuated leukotriene production.

Whilst our findings, using targeted gene disruption, clearly identify a role for group V sPLA2 in eicosanoid generation by peritoneal macrophages and in leukotriene-dependent plasma exudation, the mechanism(s) of action of group V sPLA2 are unclear. Our data, in the context of the existing literature, are consistent with a role for group V sPLA2 in amplifying the response to cPLA2α (16;18;21). Nevertheless, the nature of this interaction is poorly defined. It may involve secretion of group V sPLA2 from the cell with subsequent internalization through binding to caveoli (16). It might be due to the capacity of group V sPLA2 for interfacial binding to phosphatidylcholine, providing direct release of arachidonic acid from cell membrane phospholipids (41). Or, as recently described for human eosinophils (42), group V sPLA2 may be internalized for direct action at the perinuclear membrane. However, each of these postulated mechanisms of action requires the prior secretion of the enzyme and its subsequent internalization for action in an autocrine or paracrine manner. Our immunofluorescence data indicates prominent perinuclear accentuation of staining for group V sPLA2 (Fig. 2). The perinuclear region is a prominent location for enzymes of eicosanoid biosynthesis, either constitutively (43;44) or after translocation in response to calcium flux (4;45;46). Thus, group V sPLA2 may act intracellularly, without a requirement for prior secretion, to amplify the effects of translocated cPLA2α.

In summary, this is the first report of mice with targeted disruption of group V sPLA2. Our studies reveal the participation of the enzyme in zymosan-induced eicosanoid generation both in vitro and in vivo and suggest a role for the enzyme in acute innate immune responses.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Luis A. Sanchez-Perez for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grants HL36110, HL070946, HL07718, and AI40171; an award to MJG from The Sandler Family Supporting Foundation; an American Lung Association Clinical Investigator Award, CI-011-N; Programa de Fixação de Pesquisadores, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico-PROFIX/CNPq, Brazil; an International Research Grant from the Japan Eye Bank and by the Kowa Life Science Foundation; and the NATO Advanced Fellowship Program.

Abbreviations used: DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; HBSS–, Hanks’ balanced salt solution without Mg2+ or Ca2+; HBA, HBSS– containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin; LT, leukotriene; PCG buffer, 25 mM Pipes, 110 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1mM CaCl2, 1 g/L glucose, pH 7.4; PGHS, prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase; PLA2, phospholipase A2; cPLA2, cytosolic phospholipase A2; sPLA2, secretory phospholipase A2; PG, prostaglandin.

References

- 1.Six AD, Dennis EA. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2000;1488:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz BL, Arm JP. Prostaglandins Leukot.Essent.Fatty Acids. 2003;69:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(03)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark JD, Lin LL, Kriz RW, Ramesha CS, Sultzman LA, Lin AY, Milona N, Knopf JL. Cell. 1991;65:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90556-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNish RW, Peters-Golden M. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 1993;196:147–153. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Underwood KW, Sung C, Kriz RW, Chang XJ, Knopf JL, Lin L-L. J.Biol.Chem. 1998;273:21926–21932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickard RT, Strifler BA, Kramer RM, Sharp JD. J.Biol.Chem. 1999;274:8823–8831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valentin E, Lambeau G. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2000;1488:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross RW. Journal of Lipid Mediators & Cell Signalling. 1995;12:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0929-7855(95)00014-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ackermann EJ, Dennis EA. J.Biol.Chem. 1994;269:9227–9233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tjoelker LW, Stafforini DM. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2000;1488:102–123. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uozumi N, Kume K, Nagase T, Nakatani N, shii S, Tashiro F, Komagata Y, Maki K, kuta K, Ouchi Y, Miyazaki J, Shimizu T. Nature. 1997;390:618–622. doi: 10.1038/37622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonventre JV, Huang Z, Taheri MR, O’Leary E, Li E, Moskowitz MA, Sapirstein A. Nature. 1997;390:622–625. doi: 10.1038/37635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gijon MA, Spencer DM, Siddiq AR, Bonventre JV, Leslie CC. J.Biol.Chem. 2000;275:20146–20156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908941199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujishima H, Sanchez Meija R, Bingham CO, III, Lam BK, Sapirstein A, Bonventre JV, Austen KF, Arm, J. P. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1999;96:4803–4807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakatani N, Uozumi N, Kume K, Murakami M, Kudo I, Shimizu T. Biochem.J. 2000;352:311–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murakami M, Shimbara S, Kambe T, Kuwata H, Winstead MV, Tischfield JA, Kudo I. J.Biol.Chem. 1998;273:14411–14423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami M, Koduri RS, Enomoto A, Shimbara S, Seki M, Yoshihara K, Singer A, Valentin E, Ghomashchi F, Lambeau G, Gelb MH, Kudo I. J.Biol.Chem. 2001;276:10083–10096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han WK, Sapirstein A, Hung CC, Alessandrini A, Bonventre JV. J.Biol.Chem. 2003;278:24153–24163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300424200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balsinde J, Barbour SE, Bianco ID, Dennis EA. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1994;91:11060–11064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balboa MA, Balsinde J, Winstead MV, Tischfield JA, Dennis EA. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:32381–32384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balsinde J, Dennis EA. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:6758–6765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shinohara H, Johnson CA, Balsinde J, Dennis EA. J.Biol.Chem. 2000;274:12263–12268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tischfield JA. J.Biol.Chem. 1997;272:17247–17250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reddy ST, Herschman HR. J.Biol.Chem. 1997;272:3231–3237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bingham CO, III, Murakami M, Fujishima H, Hunt JE, Austen KF, Arm JP. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:25936–25944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.25936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bingham CO, III, Fijneman RJA, Friend DS, Goddeau RP, Rogers RA, Austen KF, Arm JP. J.Biol.Chem. 1999;274:31476–31484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dennis EA. J.Biol.Chem. 1994;269:13057–13061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arm JP, Nwankwo C, Austen KF. J.Immunol. 1997;159:2342–2349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiu ZH, de Carvalho MS, Leslie CC. J.Biol.Chem. 1993;268:24506–24513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maekawa A, Austen KF, Kanaoka Y. J.Biol.Chem. 2002;277:20820–20824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanchez Meija RO, Lam BK, Arm JP. Am.J.Respir.Cell Mol.Biol. 2000;22:557–565. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.5.3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, Engle SJ, Seilhamer JJ, Tischfield JA. J.Biol.Chem. 1994;269:2365–2368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Degousee N, Ghomashchi F, Stefanski E, Singer A, Smart BP, Borregaard N, Reithmeier R, Lindsay TF, Lichtenberger C, Reinisch W, Lambeau G, Arm J, Tischfield J, Gelb MH, Rubin BB. J.Biol.Chem. 2002;277:5061–5073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu ZH, Gijon MA, de Carvalho MS, Spencer DM, Leslie CC. J.Biol.Chem. 1998;273:8203–8211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rouzer CA, Scott WA, Cohn ZA, Blackburn P, Manning JM. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1980;77:4928–4932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouzer CA, Scott WA, Kempe J, Cohn ZA. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1980;77:4279–4282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doherty NS, Poubelle P, Borgeat P, Beaver TH, Westrich GL, Schrader NL. pg. 1985;30:769–789. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(85)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanaoka Y, Maekawa A, Penrose JF, Austen KF, Lam BK. J.Biol.Chem. 2001;276:22608–22613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balsinde J, Balboa MA, Dennis EA. J.Biol.Chem. 2000;275:22544–22549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910163199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balsinde J, Dennis EA. EurJBiochem. 1996;235:480–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han SK, Kim KP, Koduri R, Bittova L, Munoz NM, Leff AR, Wilton DC, Gelb MH, Cho W. J.Biol.Chem. 1999;274:11881–11888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munoz NM, Kim YJ, Meliton AY, Kim KP, Han SK, Boetticher E, O’Leary E, Myou S, Zhu X, Bonventre JV, Leff AR, Cho W. J.Biol.Chem. 2003;278:38813–38820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penrose JF, Spector J, Lam BK, Friend DS, Xu K, Jack RM, Austen KF. Am.J.Respir.Cell Mol.Biol. 1995;152:283–289. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.1.7599836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woods JW, Evans JF, Ethier D, Scott S, Vickers PJ, Hearn L, Heibein JA, Charleson S, Singer II. J.Exp.Med. 1993;178:1935–1946. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans JH, Spencer DM, Zweifach A, Leslie CC. J.Biol.Chem. 2001;276:30150–30160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glover S, Bayburt T, Jonas M, Chi E, Gelb MH. J.Biol.Chem. 1995;270:15359–15367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]