Abstract

We demonstrate quantitative vibrational imaging of specific lipid molecules in single bilayers using laser-scanning coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) microscopy with a lateral resolution of 0.25 μm. A lipid is spectrally separated from other molecules by using deuterated acyl chains that provide a large CARS signal from the symmetric CD2 stretch vibration around 2100 cm−1. Our temperature control experiments show that d62-DPPC has similar bilayer phase segregation property as DPPC when mixing with DOPC. By using epi-detection and optimizing excitation and detection conditions, we are able to generate a clear vibrational contrast from d62-DPPC of 10% molar fraction in a single bilayer of DPPC/d62-DPPC mixture. We have developed and experimentally verified an image analysis model that can derive the relative molecular concentration from the difference of the two CARS intensities measured at the peak and dip frequencies of a CARS band. With the above strategies, we have measured the molar density of d62-DPPC in the coexisting domains inside the DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) supported bilayers incorporated with 0–40% cholesterol. The observed interesting changes of phospholipid organization upon addition of cholesterol to the bilayer are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Lateral heterogeneity of lipid distribution in biological membranes plays a critical role in signal transduction, membrane transportation, and diseases (1–6). Because of the complexity of biological membranes, monolayers and bilayers of binary or ternary lipid mixtures have been extensively investigated to characterize the interactions responsible for phase segregation. Coexisting domains in lipid monolayers and bilayers have been observed by different techniques (7–12). Among these, fluorescence microscopy is widely used for visualizing domains in model and cellular membranes with the aid of various probes that preferentially partition into specific phases (7–13).

A key step in deepening our understanding of lipid organization is to probe the composition of these domains. Of the currently used techniques, AFM offers nanoscale resolution but lacks chemical selectivity (14–16). In fluorescence microscopy, the properties of fluorescent lipid probes could be quite different from the lipids being labeled, making it difficult to derive the molecular composition of the domains based on the partitions of the probes. Several methods for probing the membrane composition have been reported recently. By using multilamellar vesicles, NMR spectroscopy has been applied to analyze the fraction of specific deuterated lipids in different domains (17). Neutron reflection has been used to determine the composition of a supported bilayer during its formation from a surfactant/lipid mixture (18). Nevertheless, these techniques lack the spatial resolution to resolve the domains. Moreover, multilamellar vesicles might have different phase behaviors from single bilayers (19) because of the interbilayer interactions (20). Secondary ion mass spectrometry has been applied to analyze the composition of isotope-labeled supported membranes with high lateral resolution, but it is invasive and needs frozen and dehydrated samples under ultrahigh vacuum (21).

Microscopy tools based on molecular vibration signals permit noninvasive molecular imaging. Spontaneous Raman spectroscopy is a powerful tool for the study of bilayer conformation (22,23). Raman microspectroscopy has been used to map specific molecules in cells and tissues (24–26), but imaging single membranes is far beyond the sensitivity of Raman microscopy. Attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy has been used to probe conformational changes in a stack of membranes (27) and monolayer films (28). However, because the infrared technique uses longer excitation wavelengths (a few micrometers), its spatial resolution is not sufficient to map domains of a few micrometers in size (29).

The above problems encountered in linear vibration microscopy is circumvented by the development of coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) microscopy (30). CARS is a four-wave mixing process in which the interaction of a pump field  and a Stokes field

and a Stokes field  with a sample generates an anti-Stokes field

with a sample generates an anti-Stokes field  at the frequency

at the frequency  (31,32). The vibrational contrast in CARS microscopy arises from the signal enhancement when

(31,32). The vibrational contrast in CARS microscopy arises from the signal enhancement when  is tuned to a Raman-active vibrational band. The first CARS microscope was constructed with a non-collinear beam geometry (33). The use of collinear and tightly focused laser beams significantly improved the image quality (34). The major drawback of CARS microscopy is the existence of a nonresonant background that is mainly from the medium surrounding the object. A variety of methods (35–39) including epi-detection (36) have been developed to suppress the nonresonant background in a CARS image. CARS microscopy has been used to image proteins (37), liposomes (40,41), nucleic acids (42), biological water (43,44), polymer films (45), myelin figures (46), and myelin sheath (47). This technique is very sensitive to lipid membranes because the coherent addition of CARS from the large number of CH2 groups in a phospholipid membrane leads to a considerable signal (34). Detection of model and cellular membranes has been demonstrated (42,48,49). CARS microscopy has been used to probe lipid domains in giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) (50).

is tuned to a Raman-active vibrational band. The first CARS microscope was constructed with a non-collinear beam geometry (33). The use of collinear and tightly focused laser beams significantly improved the image quality (34). The major drawback of CARS microscopy is the existence of a nonresonant background that is mainly from the medium surrounding the object. A variety of methods (35–39) including epi-detection (36) have been developed to suppress the nonresonant background in a CARS image. CARS microscopy has been used to image proteins (37), liposomes (40,41), nucleic acids (42), biological water (43,44), polymer films (45), myelin figures (46), and myelin sheath (47). This technique is very sensitive to lipid membranes because the coherent addition of CARS from the large number of CH2 groups in a phospholipid membrane leads to a considerable signal (34). Detection of model and cellular membranes has been demonstrated (42,48,49). CARS microscopy has been used to probe lipid domains in giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) (50).

To fully appreciate the capability of CARS microscopy, it is important to develop strategies for acquiring quantitative information about lipid distribution in different membrane domains. In this article, we present our approaches to overcome the following technical challenges and demonstrate quantitative CARS imaging of lipid domains in single bilayers.

How to probe a specific molecule? To spectrally separate different lipid molecules, we make use of deuteration that changes the Raman shift but does not alter the molecular structure. Isotope-labeled lipids including chain-deuterated lipids have been recently used to investigate lipid organization with NMR spectroscopy (16,17,51). The abundant CD2 groups in lipid molecules with fully deuterated acyl chains (e.g., d62-DPPC) produce a large CARS signal. The symmetric CD2 stretch vibration band located around 2100 cm−1 is isolated from any Raman band of natural biological molecules, including the C-H vibration bands in the region of 2800–3000 cm−1. Unlike fluorescent lipid probes used as a marker of domains, d62-DPPC is directly used as a component of the bilayer in our CARS imaging experiments. To evaluate the effect of deuteration on lipid organization, we compared the formation of domains and their miscibility transition temperatures between the two-component GUVs composed of DOPC/DPPC and DOPC/d62-DPPC. The domains display the same pattern in both GUV samples. The only difference lies in that GUVs composed of d62-DPPC/DOPC have a 4°C lower miscibility transition temperature than GUVs composed of DPPC/DOPC. Therefore, our CARS measurements are able to reflect the nature of lipid organization.

How to achieve subbilayer sensitivity? We have pushed the sensitivity limit to probe a specific component in a single bilayer of lipid mixtures. The excitation is optimized by using 2.5-ps excitation pulses that match the line widths of the CH2 and CD2 stretch Raman bands. Epi-detection is used to avoid the forward-going nonresonant background that is mainly contributed by the bulk medium (35,36). The residual nonresonant background is removed by comparing the difference between two CARS images taken at the peak and dip of a CARS band. We have also built an external detection channel using a photomultiplier tube with high quantum efficiency at the CARS wavelengths. With the above efforts, we have been able to obtain a high vibrational contrast from 10% d62-DPPC in a single DPPC/d62-DPPC bilayer.

How to convert the CARS intensity into molecular concentration? We have demonstrated theoretically and experimentally an image analysis model that linearly relates the number of vibrational oscillators in the excitation volume to the difference between the CARS intensity measured at the peak and that at the dip frequency of a CARS band.

After a systematic characterization of our method, we present an imaging study of the planar bilayers of DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) mixtures containing 0, 10, 20, 30, and 40% (molar percentage) cholesterol. An ideal system for testing our method would be a single bilayer with determined lipid compositions in different domains. Unfortunately, such information has not been obtained by other existing techniques. We choose the binary mixture of DOPC/d62-DPPC and the ternary mixture of DOPC/d62-DPPC/cholesterol for the following reasons. First, Lentz et al. have obtained the phase diagram of DOPC/DPPC mixtures in multilamellar liposomes and small unilamellar vesicles using fluorescence depolarization measurements (19). They have shown that DOPC and DPPC are not miscible at room temperature. Second, Keller and co-workers have systematically studied the miscibility of the ternary mixture of DOPC, DPPC, and cholesterol in GUVs (12). Coexisting gel and liquid domains were observed in GUVs of DOPC/DPPC, whereas coexisting liquid-ordered (Lo) and liquid-disordered (Ld) domains were observed in the ternary mixture. Third, using NMR spectroscopy, Veatch et al. have obtained the fraction of d62-DPPC in the Lo and Ld phases of multilamellar liposomes composed of DOPC, d62-DPPC, and cholesterol (17). These studies make the bilayers composed of DOPC/d62-DPPC/cholesterol a good system for us to evaluate the CARS imaging method.

Domains in GUVs have been observed using CARS microscopy (50). However, we do not use GUVs for quantitative CARS imaging measurements because of their translation and undulation motions. We use supported bilayers because their planar geometry facilitates image acquisition and interpretation. To prepare planar lipid domains, we first make GUVs of certain lipid compositions using the electroformation method (52), and then rupture the GUVs to a cleaned coverslip and form bilayer patches. The domains become static in the supported bilayer patches (53), facilitating CARS imaging of the same sample at different Raman shifts. We present quantitative measurements of the partition of d62-DPPC between the two coexisting domains in single DOPC/d62-DPPC bilayers at different levels of cholesterol. The roles of cholesterol in lipid bilayer organization are discussed on the basis of our CARS imaging results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Lipids

DOPC, DPPC, d62-DPPC, and cholesterol were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) and used without further purification. BODIPY PC was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Preparation of supported lipid bilayers

Homogeneous supported bilayers are prepared by the small unilamellar vesicle (SUV) fusion method (54). A chloroform solution of a lipid mixture of desired molar ratio is evaporated under a nitrogen stream and then vacuumed for 3 h. The lipid mixture is rehydrated with a HEPES buffer (50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH = 7.0). The suspension is sonicated in an ultrasonic cleaner (No. G112SP1, Laboratory Supplies, Hicksville, NY) for 10 min and then centrifuged at 13200 rpm for 5 min. The SUV solution is mixed with an equal amount of HEPES buffer, which has a higher concentration of NaCl (250 mM) to increase the vesicle fusion speed. The mixed solution is immediately dropped in a perfusion chamber attached on a coverslip. The coverslips have been cleaned with a 7× detergent (No. IC7667094, ICN, Irvine, CA) and then baked at 600°C for 6 h. The DPPC and d62-DPPC samples are incubated at 60°C for 1 h and then cooled slowly down to room temperature at an average cooling rate of 0.3°C/min. The DOPC sample is directly incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The residual SUVs are washed away using the same buffer.

Preparation of giant unilamellar vesicles and planar bilayer patches

Giant unilamellar vesicles are prepared using the electroformation method (52). The total concentration of the lipid mixtures in a chloroform solution is 0.2 μmol/mL, containing 0.4 molar percent of BODIPY PC. A 10-μL glass syringe is used to add 6 μL of the mixture solution onto each of the two parallel Pt wires. After 1 h vacuum, the wires are inserted into a glass cell (No. 83301-01, Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) filled with milli-Q water. The cell is then sealed with wax. Electroformation is carried out by using a 10-Hz sine wave with a Vpeak-peak of 3 V for 2 h at 50°C. After that a 4-Hz sine wave at the same voltage is applied to dislodge the GUVs from the Pt wires. Lipid domains are formed after the GUVs are cooled slowly down to the room temperature. To make bilayer patches, the GUV solution is mixed with an equal amount of the HEPES buffer (100 mM NaCl) to assist fusion of GUVs to the glass substrate (53). After at least 1 h incubation at room temperature, the adjacent GUVs are fused and then rupture onto the coverslip to form planar bilayer patches.

CARS imaging

A schematic of our CARS microscope is shown elsewhere (47). Two co-linearly combined 2.5-ps pulse trains at frequencies ωp and ωs are generated from two synchronized Ti:sapphire oscillators (Mira 900, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA). A Pockels' cell (No. 350-160, Conoptics, Danbury, CT) is used to lower the repetition rate to 3.8 MHz. CARS images are acquired by raster scanning the two laser beams using a confocal microscope (FV300/IX70, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). A water immersion objective with 1.2 N.A. is used to focus the laser beams into the sample. The confocal pinhole is not used for CARS imaging, which has a lateral resolution of 0.23 μm and an axial resolution of 0.75 μm (42). The forward and backward CARS signals around 600 nm are collected by an air condenser (N.A. = 0.55) and the water objective, respectively, and are simultaneously detected by two photomultiplier tubes (R3896 and H7422-40, Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan) with a quantum efficiency of 0.15 and 0.4, respectively.

The large forward-detected CARS (F-CARS) signal is dominated by the nonresonant background from glass and water. The epi-detected CARS (E-CARS) images display high vibrational contrast because the nonresonant CARS background from the surrounding medium is mostly canceled out by the destructive interference among the backward CARS fields (36). Due to the refractive index mismatch between water and the coverslip, the forward CARS field generated from glass is partially reflected and coherently mixed with the backward resonant CARS field from the bilayer (30). It should be noted that the back-reflection amplitude highly depends on the axial position of the foci relative to the water/glass interface. To record the CARS images at the same focal depth, we carefully adjust the height of the objective lens to keep the F-CARS/E-CARS intensity ratio in a bare glass area to be the same. We also realize that both F-CARS and E-CARS intensities change with the detector efficiency at different wavelengths. To perform quantitative analysis, we normalize the E-CARS image intensity by the nonresonant F-CARS intensity from the glass/water interface. This preserves the vibrational contrast but rules out the signal change due to other factors.

The ratio of the pump to Stokes beam power was set as 2:1 to maximize the CARS signal at a certain excitation power. The pulse duration is very repeatable when we tune the laser wavelengths back and forth. We have been able to reproduce the CARS data owing to the high stability of Ti:Sapphire lasers.

CARS image analysis

We have developed a model for calculating the density of a specific vibrational oscillator in the excitation volume from the CARS intensities based on the following assumptions: 1), the resonant CARS signal arises from an isolated Raman band. This assumption is not valid for the symmetric CH2 stretch vibration that is spectrally overlapped with the antisymmetric CH2 stretch band and the CH3 stretch bands. However, it holds for the symmetric CD2 stretch band of d62-DPPC. 2), The nonresonant background from the scatterer is negligible compared to that from the surrounding medium. We have observed that the contrast for a bilayer patch on a coverslip is negligible when  is tuned away from Raman resonance. Therefore, this assumption is valid for either forward- or epi-detected CARS signals from a single bilayer. 3), The resonant CARS signal is much smaller than the nonresonant background (

is tuned away from Raman resonance. Therefore, this assumption is valid for either forward- or epi-detected CARS signals from a single bilayer. 3), The resonant CARS signal is much smaller than the nonresonant background ( ). For a supported bilayer of pure d62-DPPC, the contrast, ICARS(bilayer) / ICARS(no bilayer) − 1, is measured to be 0.15 (see Fig. 1 A). Therefore, this assumption holds for the epi-detected resonant CARS signal from CD2 groups in a single bilayer.

). For a supported bilayer of pure d62-DPPC, the contrast, ICARS(bilayer) / ICARS(no bilayer) − 1, is measured to be 0.15 (see Fig. 1 A). Therefore, this assumption holds for the epi-detected resonant CARS signal from CD2 groups in a single bilayer.

FIGURE 1.

CARS (•, solid line) spectra of a single supported bilayer of d62-DPPC (A) and DOPC (B). The CARS spectra were obtained from a series of epi-detected CARS images taken at the room temperature of 23°C. The pump beam wavelength was fixed at 709.8 nm whereas the Stokes beam wavelength was tuned to generate different Raman shifts. The interference between the resonant signal from the bilayer and the nonresonant background results in the dispersive spectral profiles. Spontaneous Raman spectra (dashed lines) of d62-DPPC and DOPC multilamellar liposomes were recorded on a homebuilt portable Raman imaging system equipped with a 632.8-nm He-Ne laser. The CARS images taken at the peak and the dip position are shown on the right side. The image brightness scales with the CARS intensity. The image size is 50 μm.

The CARS signal arises from the third-order susceptibility,  of a material (55). When one Raman band is involved,

of a material (55). When one Raman band is involved,  can be written as

can be written as

|

(1) |

where δ represents the detuning,  Ω is the vibrational frequency. Γ is the halfwidth at half maximum of an isolated Raman line. A is a constant representing the Raman scattering strength; n is the number of oscillators with the vibrational frequency Ω.

Ω is the vibrational frequency. Γ is the halfwidth at half maximum of an isolated Raman line. A is a constant representing the Raman scattering strength; n is the number of oscillators with the vibrational frequency Ω.  represents the nonresonant contribution and is a constant in the absence of electronic resonance (32).

represents the nonresonant contribution and is a constant in the absence of electronic resonance (32).

We consider a Raman scatterer (e.g., a lipid bilayer) surrounded by a medium that only contributes to the nonresonant background ( ). Assuming that the nonresonant background from the scatterer is negligible, the CARS intensity can be written as

). Assuming that the nonresonant background from the scatterer is negligible, the CARS intensity can be written as

|

(2) |

The second item in the right side of Eq. 2 contributes to a constant background. The third term disperses the CARS spectral profile (32) and results in a peak (ω+) and dip (ω−) at

|

(3) |

For a weak Raman scatterer ( ), the difference (

), the difference ( ) between the intensities near the peak position (

) between the intensities near the peak position ( ) and the dip position (

) and the dip position ( ) is proportional to

) is proportional to  The nonresonant background from surrounding medium, Ibg, is proportional to

The nonresonant background from surrounding medium, Ibg, is proportional to  We have

We have

|

(4) |

The value of  is proportional to the number of specific vibrational oscillators (e.g., the CD2 groups) in the excitation volume. The above model can be applied to both F-CARS and E-CARS. In our experiment, Ibg is measured as the E-CARS intensity from the bare coverslip part of the CARS images. Because the excitation area is much smaller than the domain sizes,

is proportional to the number of specific vibrational oscillators (e.g., the CD2 groups) in the excitation volume. The above model can be applied to both F-CARS and E-CARS. In our experiment, Ibg is measured as the E-CARS intensity from the bare coverslip part of the CARS images. Because the excitation area is much smaller than the domain sizes,  is proportional to the density of specific vibrational oscillators in a membrane domain. CARS intensities averaged over a constant area in a certain domain are used in our calculation.

is proportional to the density of specific vibrational oscillators in a membrane domain. CARS intensities averaged over a constant area in a certain domain are used in our calculation.

Laser scanning fluorescence imaging

To correlate the CARS images with the membrane phases, we have labeled the bilayers with BODIPY PC that preferentially partitions into the more disordered phase (56,57). The peak emission wavelength of BODIPY PC at 510 nm is spectrally separated from the CARS wavelengths around 600 nm. Laser-scanning fluorescence imaging is carried out using the same microscope. A 488-nm Ar+ laser is used to excite BODIPY PC. For each bilayer sample, a fluorescence image is acquired before the CARS images. The fluorescent probe is quickly bleached by the picosecond excitation pulses and does not contribute to any contrast in the CARS images. Fluorescence images of GUVs and bilayer patches at different temperatures are acquired using a homebuilt temperature-controlled chamber.

RESULTS

CARS spectra of single lipid bilayers

Because of the interference between the vibrationally resonant CARS signal and the nonresonant background, the spectral profile of a CARS band differs from the corresponding Raman band (32). To identify the optimal wavelength for CARS imaging, we have recorded the CARS contrast spectra of a single DOPC bilayer and a single d62-DPPC bilayer. The CARS spectra shown in Fig. 1 were obtained from a series of epi-detected CARS images at different Raman shifts. Each image covers a bilayer part and a bare coverslip part. The CARS contrast was calculated as the signal difference between the bilayer and the bare coverslip part divided by the signal from the bare coverslip. Because of the interference between the resonant signal from the bilayer and the back-reflected nonresonant background, the peak positions for the CARS bands of symmetric CH2 and CD2 stretch vibration appear at 2840 and 2080 cm−1, red-shifted from the center vibration frequencies at 2850 and 2100 cm−1, respectively. Meanwhile, a dip is observed around 3000 and 2125 cm−1 for the CH2 and CD2 vibration, respectively. Accordingly, we observed a positive contrast at the peak frequency and a negative contrast at the dip frequency in the CARS images shown beside the spectra. It should be noted that the spectral profiles in Fig. 1, A and B, are quite different. The CH2 stretch vibration spectrum in the 2700–3100-cm−1 region is complicated by several spectrally overlapped vibrational bands (48,49), whereas the CD2 vibrational band exhibits a much simpler profile in the 2000–2200-cm−1 region for the following reasons. The 2700–3100-cm−1 region contains the Raman bands of symmetric and antisymmetric CH2 and CH3 stretch vibration (23). The Raman cross section for the antisymmetric CH2 vibration is comparable to that for the symmetric CH2 vibration. The CH3 groups that are mainly located in the choline region have higher stretch vibration frequencies. The antisymmetric CH2 vibration and the CH3 vibration cancel the dip of the symmetric CH2 stretch band and create a new dip around 3000 cm−1. On the other hand, the antisymmetric CD2 stretch band around 2200 cm−1 is much weaker than the symmetric CD2 stretch band around 2100 cm−1. Additionally, the polar head of d62-DPPC is not deuterated. Only the stretch vibrational bands of the two CD3 groups in the deuterated acyl chains could interfere with the 2100-cm−1 band. Therefore, the CD2 symmetric stretch vibration band can be treated as an isolated Raman band that exhibits a symmetrically dispersed CARS spectral profile (Fig. 1 A).

CARS intensity versus d62-DPPC molar fraction

Supported bilayers composed of different molar fractions of DPPC and d62-DPPC were used to test the sensitivity and the image analysis model. Fig. 2 A shows the CARS images of a bilayer composed of 10% d62-DPPC and 90% DPPC taken at room temperature. The nonresonant background is removed by subtracting the image at the dip frequency from the image at the peak frequency. In the difference image (Fig. 2 A, right), we observed a clear vibrational contrast from the 10% d62-DPPC in the bilayer whereas only noise in the bare coverslip part. Such sensitivity permits the detection of specific lipid molecules in different domains.

FIGURE 2.

(A) CARS images of a bilayer composed of 90% DPPC and 10% d62-DPPC taken at 2080 cm−1 (left) and 2125 cm−1 (middle), respectively. The right image is the difference image obtained by subtracting the image at 2080 cm−1 from that at 2125 cm−1. The straight edge of the bilayer was created by drawing the bilayer through the air/water interface (54). (B) The difference CARS images of DPPC/d62-DPPC bilayers. The molar percentages of d62-DPPC are marked above each image. (C and D) The solid circles with error bars show the  values of CD2 and CH2 groups as a function of the molar percentages of d62-DPPC and DPPC. The linear fit equations and results (solid lines) are also shown.

values of CD2 and CH2 groups as a function of the molar percentages of d62-DPPC and DPPC. The linear fit equations and results (solid lines) are also shown.

Fig. 2 B shows the difference CARS images between 2080 and 2125 cm−1 for bilayers at different d62-DPPC molar percentages. The gel phase bilayers are homogeneous judging from the CARS contrast. We have calculated the values of  for the CD2 groups from the CARS intensity difference between 2080 and 2125 cm−1. The validity of our model (Eq. 4) can be seen from the linear relationship between the measured

for the CD2 groups from the CARS intensity difference between 2080 and 2125 cm−1. The validity of our model (Eq. 4) can be seen from the linear relationship between the measured  value and the molar fraction of d62-DPPC in the sample (Fig. 2 C). With 0% d62-DPPC, we can hardly see any contrast (Fig. 2 B), indicating that the nonresonant background is completely removed in the difference images.

value and the molar fraction of d62-DPPC in the sample (Fig. 2 C). With 0% d62-DPPC, we can hardly see any contrast (Fig. 2 B), indicating that the nonresonant background is completely removed in the difference images.

We have also taken the CARS images of the same samples at 2840 and 3000 cm−1 and performed the same calculation for the CH2 stretch band. As shown in Fig. 2 D, the obtained  value is still linear with respect to the molar fraction of DPPC although several spectrally overlapped Raman bands are located in the CH2 vibration region. The ratio of

value is still linear with respect to the molar fraction of DPPC although several spectrally overlapped Raman bands are located in the CH2 vibration region. The ratio of  at CH2 vibration for 100% DPPC to that for 100% d62-DPPC (0% DPPC) is 17.8/2.1 = 8.5. This value agrees with the 8:1 ratio between the 32 CH2 groups in DPPC and the four CH2 groups in the polar head of d62-DPPC.

at CH2 vibration for 100% DPPC to that for 100% d62-DPPC (0% DPPC) is 17.8/2.1 = 8.5. This value agrees with the 8:1 ratio between the 32 CH2 groups in DPPC and the four CH2 groups in the polar head of d62-DPPC.

Comparison of phase segregation in d62-DPPC-containing and DPPC-containing bilayers

Before we study the lipid domains with CARS microscopy, we have evaluated the effect of chain deuteration on the bilayer phase segregation. The chain melting temperature (Tm) of DPPC is 42°C. The Tm of d62-DPPC is lowered to 37.75°C due to the chain deuteration (58,59). Fig. 3, A and B, display the fluorescence images of the GUVs composed of DOPC/DPPC (1:1) and DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) taken at different temperatures. The DOPC/d62-DPPC GUVs are segregated into coexisting liquid and gel phases at room temperature as the DOPC/DPPC GUVs, with the liquid phase labeled by BODIPY PC. The miscibility temperature for the DOPC/DPPC GUVs is 35°C, consistent with previous measurement (60). The miscibility temperature for the DOPC/d62-DPPC GUVs is lowered by 4°C because of the deuteration.

FIGURE 3.

Fluorescence images of DOPC/DPPC (1:1) GUVs (A), DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) GUVs (B), and DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) bilayer patches (C) measured with a homebuilt temperature-controlled chamber. Bar length = 20 μm.

When the GUVs rupture into bilayer patches, the lipid domains become nearly immobile in the bilayer patches as shown in previous studies (53). Only two BODIPY PC fluorescence intensities were observed, indicating that the patches were single bilayers and the domains symmetrically occupy both leaflets (11). To evaluate the effect of the glass substrate on the miscibility temperature of bilayers, we have monitored a single DOPC/DPPC (1:1) patch in a temperature-controlled chamber. As shown in Fig. 3 C, the domains become smaller with increasing sample temperature and eventually disappear at 37°. The higher miscibility temperature for supported bilayer patches is likely due to the stabilizing effect of the substrate (15). In summary, deuteration of hydrocarbon chains lowers the miscibility temperature between DPPC and DOPC by 4°C, but the domain pattern is the same in the GUVs containing deuterated and nondeuterated lipids.

Two-component bilayers

After a systematic characterization of the method, we studied the DOPC/d62-DPPC bilayer patches prepared by rupturing GUVs on a chambered coverslip. Fig. 4, A–D, shows the E-CARS images of the DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) bilayer at the peak and dip positions of CH2 and CD2 vibration, respectively. Similar to the bilayers of DOPC and d62-DPPC shown in Fig. 1, we observed an inversion of the CARS contrast when  was tuned from the peak to the dip position for both CH2 and CD2 stretch bands. The bright CD2 vibration contrast shown in the difference CARS image (Fig. 4 F) demonstrates that d62-DPPC is highly concentrated in the gel phase that is not labeled by BODIPY PC (Fig. 4 E). Noting that the CARS signal is affected by molecular orientation (44), we monitored the CARS signal while rotating the excitation polarization direction in the x-y plane. The CARS signal is invariant, indicating that the ordered phase is likely in the Pβ′ phase but not in the tilted Lβ′ phase. The Pβ′ phase has been observed as a rippled phase in AFM studies (61). The molecular axis in the Pβ′ phase is vertical to the substrate, thus the CARS intensities reflect the density of specific molecules in the excitation volumes. It is interesting that the bilayer patch displays little contrast at the CH2 stretch vibration frequency (Fig. 4 A). The resonant CH2 signal from the liquid phase is mainly contributed by the abundant DOPC molecules. The resonant CH2 signal from the gel phase could be contributed by the d62-DPPC molecules that have CH2 groups in the head region and also by the DOPC molecules that are incorporated into the gel phase. A quantitative analysis is presented below.

was tuned from the peak to the dip position for both CH2 and CD2 stretch bands. The bright CD2 vibration contrast shown in the difference CARS image (Fig. 4 F) demonstrates that d62-DPPC is highly concentrated in the gel phase that is not labeled by BODIPY PC (Fig. 4 E). Noting that the CARS signal is affected by molecular orientation (44), we monitored the CARS signal while rotating the excitation polarization direction in the x-y plane. The CARS signal is invariant, indicating that the ordered phase is likely in the Pβ′ phase but not in the tilted Lβ′ phase. The Pβ′ phase has been observed as a rippled phase in AFM studies (61). The molecular axis in the Pβ′ phase is vertical to the substrate, thus the CARS intensities reflect the density of specific molecules in the excitation volumes. It is interesting that the bilayer patch displays little contrast at the CH2 stretch vibration frequency (Fig. 4 A). The resonant CH2 signal from the liquid phase is mainly contributed by the abundant DOPC molecules. The resonant CH2 signal from the gel phase could be contributed by the d62-DPPC molecules that have CH2 groups in the head region and also by the DOPC molecules that are incorporated into the gel phase. A quantitative analysis is presented below.

FIGURE 4.

E-CARS (A–D) and fluorescence (E) images of a DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) bilayer patch acquired at the room temperature of 23°C. (F) The difference image obtained by subtracting image D from image C. Each CARS image was an average of 40 frames. The acquisition time was 0.44 s for each frame of 256 × 256 pixels. The wavelength of the pump beam was fixed at 709.8 nm. The pump and Stokes power at the sample was 3.0 and 1.4 mW, respectively, at a repetition rate of 2.56 MHz. The parameters are applicable to other CARS images. No photodamage of the bilayer was observed. The fluorescent probe BODIPY PC labels the Ld phase of the bilayers. The small dots in the images are fused vesicles. Bar length = 10 μm.

Using Eq. 4 and the CARS images shown in Fig. 4, we have calculated the values of  for the CD2 and CH2 groups in the gel and liquid domains. The results are illustrated in Fig. 5. For the DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) bilayer, the

for the CD2 and CH2 groups in the gel and liquid domains. The results are illustrated in Fig. 5. For the DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) bilayer, the  value of CD2 is 8.40 and 0.96 for the gel and liquid phase, respectively. The

value of CD2 is 8.40 and 0.96 for the gel and liquid phase, respectively. The  value of CD2 for pure d62-DPPC bilayers is measured to be 11.41.

value of CD2 for pure d62-DPPC bilayers is measured to be 11.41.

FIGURE 5.

The values of  for the CH2 (A) and the CD2 group (B) in the Lo (or gel) and Ld domains. The error bar represents the standard deviation of five different patches of each sample. The bilayer compositions are marked below the histograms. The bilayers labeled with cholesterol percentages contain 1:1 DOPC/d62-DPPC. The bilayer with 10% cholesterol is in a fluid ordered phase. See text for details.

for the CH2 (A) and the CD2 group (B) in the Lo (or gel) and Ld domains. The error bar represents the standard deviation of five different patches of each sample. The bilayer compositions are marked below the histograms. The bilayers labeled with cholesterol percentages contain 1:1 DOPC/d62-DPPC. The bilayer with 10% cholesterol is in a fluid ordered phase. See text for details.

In our temperature-control experiment of the pure d62-DPPC bilayer patch, we have observed that the  value decreases by two times when the temperature is increased from 23 to 46°C. This implies that d62-DPPC in the gel and liquid phase has different configuration and gives different CARS intensities. To evaluate the molar density of d62-DPPC and DOPC in each domain, we make two assumptions. First, d62-DPPC in the gel (or Ld) domains has the same configuration as in the pure d62-DPPC bilayer in the gel (or Ld) phases, respectively. The same assumption is made for DOPC. Second, d62-DPPC and DOPC have the same area per molecules in either the gel or the liquid domain. This assumption is supported by the x-ray measurements of pure lipid bilayers (62). Based on the above assumptions, the molar density of d62-DPPC in the gel phase is calculated to be 8.40/11.41 = 0.74. The molar density of DOPC in the gel phase is 1.0 − 0.74 = 0.26.

value decreases by two times when the temperature is increased from 23 to 46°C. This implies that d62-DPPC in the gel and liquid phase has different configuration and gives different CARS intensities. To evaluate the molar density of d62-DPPC and DOPC in each domain, we make two assumptions. First, d62-DPPC in the gel (or Ld) domains has the same configuration as in the pure d62-DPPC bilayer in the gel (or Ld) phases, respectively. The same assumption is made for DOPC. Second, d62-DPPC and DOPC have the same area per molecules in either the gel or the liquid domain. This assumption is supported by the x-ray measurements of pure lipid bilayers (62). Based on the above assumptions, the molar density of d62-DPPC in the gel phase is calculated to be 8.40/11.41 = 0.74. The molar density of DOPC in the gel phase is 1.0 − 0.74 = 0.26.

Analysis for the CH2 group is complicated because both DOPC and d62-DPPC contribute to the CH2 signal. The  value for CH2 in a pure DOPC bilayer is 9.73. We measured the d62-DPPC bilayer at 46°C and obtained the

value for CH2 in a pure DOPC bilayer is 9.73. We measured the d62-DPPC bilayer at 46°C and obtained the  value to be 1.02. The

value to be 1.02. The  value for the Ld phase of the DOPC/d62-DPPC bilayer is measured to be 8.03. Assume the molar fraction of DOPC is y, we have the following equation,

value for the Ld phase of the DOPC/d62-DPPC bilayer is measured to be 8.03. Assume the molar fraction of DOPC is y, we have the following equation,

|

The molar density of DOPC and d62-DPPC in the Ld domain is found to be 0.80 and 0.20, respectively.

Three-component bilayers

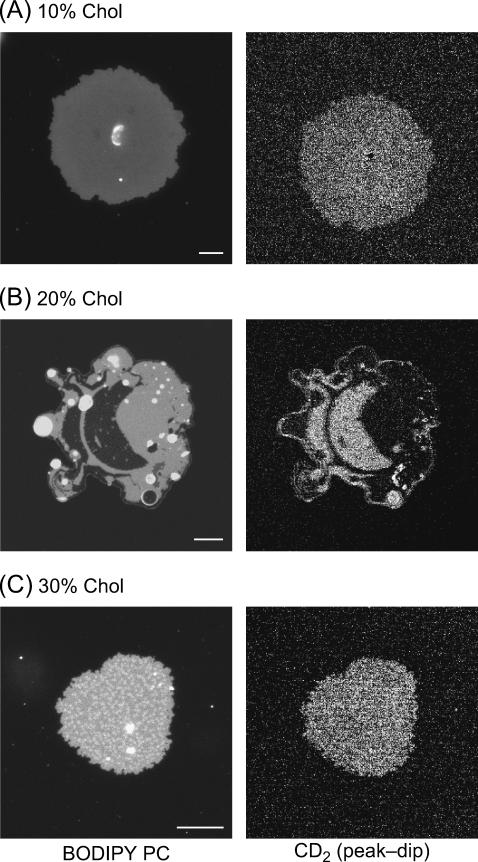

In GUVs composed of DOPC, cholesterol, and DPPC, Lo domains have been observed in fluorescence microscopy (12,63). Using CARS microscopy, we have studied the DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) bilayers incorporated with 10, 20, 30, and 40% cholesterol. At 10% cholesterol level, we did not observe large-scale domains in either GUVs or bilayer patches (see Fig. 6 A). For the 20% cholesterol sample, round Lo domains were observed in the percolating Ld domain in the GUV fluorescence images. The domains became static and exhibited irregular shapes after we ruptured the GUVs onto a coverslip (see Fig. 6 B), but the individual lipids in the bilayer patch were shown to be mobile in a fluorescence recovery after photobleaching study by Kaizuka et al. (53). For convenience, we call the observed domains in the bilayer patches as coexisting Lo and Ld domains. For the 30% cholesterol samples, the Lo phase becomes the percolating domain in some GUVs. In the bilayer patches containing 30% cholesterol, the Lo phase appears as the percolating domain (Fig. 6 C).

FIGURE 6.

E-CARS (right) and fluorescence (left) images of the DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) bilayer patches containing 10 (A), 20 (B), and 30% (C) Cholesterol. The E-CARS images are difference images obtained by subtracting the image taken at 2125 cm−1 from the image taken at 2080 cm−1. Bar length = 10 μm.

The CARS images of the DOPC/d62-DPPC(1:1)/cholesterol bilayer patches allow us to quantify the role of cholesterol in lipid organization in the bilayer patches. Quantitative analysis (see Fig. 5) was carried out in a similar way. At 10% cholesterol level, the  value for CD2 is measured to be 2.29 for the whole bilayer. For the 20% cholesterol sample, the positive contrast at the CD2 stretch vibration frequency of 2080 cm−1 (Fig. 6 B) demonstrates that d62-DPPC preferentially partitions into the Lo domain that is not labeled by BODIPY PC. The smallest domain we can identify is 0.25 μm in width, corresponding to the lateral resolution of our setup. With 20% cholesterol incorporated into the bilayer, the

value for CD2 is measured to be 2.29 for the whole bilayer. For the 20% cholesterol sample, the positive contrast at the CD2 stretch vibration frequency of 2080 cm−1 (Fig. 6 B) demonstrates that d62-DPPC preferentially partitions into the Lo domain that is not labeled by BODIPY PC. The smallest domain we can identify is 0.25 μm in width, corresponding to the lateral resolution of our setup. With 20% cholesterol incorporated into the bilayer, the  value for CD2 drops from 8.40 in the gel phase to 7.07 in the Lo phase, corresponding to a decrease of the d62-DPPC molar density from 0.74 to 0.62. Meanwhile, we find an increase of the

value for CD2 drops from 8.40 in the gel phase to 7.07 in the Lo phase, corresponding to a decrease of the d62-DPPC molar density from 0.74 to 0.62. Meanwhile, we find an increase of the  value from 0.96 to 1.32 in the Ld phase. Our observation suggests that cholesterol “drives” some d62-DPPC molecules from the more-ordered phase to the less-ordered phase. The observed change in d62-DPPC partition is accompanied by the change of the

value from 0.96 to 1.32 in the Ld phase. Our observation suggests that cholesterol “drives” some d62-DPPC molecules from the more-ordered phase to the less-ordered phase. The observed change in d62-DPPC partition is accompanied by the change of the  values for CH2. In the DOPC/DPPC (1:1) bilayer, the CH2 concentration in the gel phase is lower than that in the Ld phase. With 20% cholesterol, we observed a slightly higher CH2 concentration in the Lo phase than in the Ld phase (Fig. 5 A), indicating a larger partition of DOPC into the Lo than the gel phase.

values for CH2. In the DOPC/DPPC (1:1) bilayer, the CH2 concentration in the gel phase is lower than that in the Ld phase. With 20% cholesterol, we observed a slightly higher CH2 concentration in the Lo phase than in the Ld phase (Fig. 5 A), indicating a larger partition of DOPC into the Lo than the gel phase.

When the cholesterol level is increased to 30%, we observed a uniform CARS intensity in the whole bilayer (see Fig. 6 C). Because the BODIPY PC labeled Ld domain is ∼1 μm in size, we should be able to resolve them in the CARS image. Thus, the uniform CARS intensity indicates that the concentration difference of d62-DPPC between the Lo and Ld phase is below 10%, our detection sensitivity. With 30 and 40% cholesterol incorporated into the bilayer, the  value of CD2 for the whole bilayer is measured to be 3.28 and 2.88, respectively. The molar density is calculated to be 0.29 and 0.25, close to the molar fraction of d62-DPPC (0.35 and 0.30). This supports that the d62-DPPC/DOPC bilayers are highly compact in the presence of high-level cholesterol.

value of CD2 for the whole bilayer is measured to be 3.28 and 2.88, respectively. The molar density is calculated to be 0.29 and 0.25, close to the molar fraction of d62-DPPC (0.35 and 0.30). This supports that the d62-DPPC/DOPC bilayers are highly compact in the presence of high-level cholesterol.

DISCUSSION

Evaluation of CARS microscopy for studies of membrane organization

The major advantage of CARS is its chemical selectivity without fluorophore labeling. In our experiments, we have used the CH2 and CD2 stretch Raman bands because coherent addition of CARS radiations from the large number of CH2 or CD2 groups builds up a large signal, allowing us to probe a specific lipid with a molar concentration as low as 10% in a single bilayer. With the improvement of CARS imaging sensitivity on the basis of new generations of lasers and detectors, one will be able to use the weaker Raman bands from the polar head region to distinguish different lipid molecules without any labeling. In comparison with secondary ion mass spectrometry that probes dehydrated samples under high vacuum (21), CARS microscopy is superior in that it is noninvasive and can probe membrane samples under physiological conditions. Recently, CARS microscopy has been applied to image myelin sheath in live spinal tissues with three-dimensional spatial resolution and a penetration depth >250 μm (47).

Several strategies have been combined to push the sensitivity limit in the current work. First, we use two synchronized picosecond lasers to generate the CARS signal. Because the spectral profile of a picoseond pulse matches with the line width of most Raman bands, all the energy can be used to drive a single molecular vibration, providing much higher sensitivity than excitations with femtosecond pulses (35). Second, instead of using amplified laser pulses at low repetition rates, we use synchronized Ti:sapphire oscillators and pulse picking devices to generate two pulse trains with pulse energy of a few nanojoules and repetition rate of a few megahertz. This excitation scheme not only avoids nonlinear photodamage, but also permits high-speed imaging. Third, we make use of epi-detection that avoids the forward-going nonresonant background arising from the solvent and the glass substrate. Fourth, by measuring the intensity difference at the peak and the dip positions, we have not only removed the back-reflected nonresonant background from glass/water interface, but also utilized the dispersive feature of a CARS band to further increase the resonant signal. This is superior over other methods such as polarization CARS imaging wherein the resonant signal can be significantly reduced by polarization sensitive detection (37). These careful designs allowed us to generate a clear vibration contrast from d62-DPPC with a 10% molar concentration in a single bilayer (see Fig. 2). We should note that with picosecond excitation, two images need to be acquired to derive quantitative concentration information. This can be avoided by multiplex CARS microscopy that uses a narrowband pump beam and a broadband Stokes beam (40,41,64), providing that the CARS spectral imaging sensitivity will be significantly improved with new generations of electron multiplying CCDs. In addition to molecular mapping, the polarization sensitivity (44) and the spectral characterization capability (40,41,65) can be applied to study the ordering degree and conformation of lipid molecules without any labeling. Finally, the lateral resolution of far-field CARS microscopy is ∼0.25 μm. Thus, we could not probe the nanoscale domains that have been observed by AFM (15). This problem could be solved by using near-field CARS microscopy (66).

Implications of the role of cholesterol in bilayer organization

It is known that cholesterol broadens the gel to liquid phase transition of saturated lipids (67) and creates the Lo phase in the bilayer (68). It is generally believed that cholesterol associates strongly with saturated lipid and poorly with the unsaturated lipids (69). However, cholesterol may have complicated interactions with phospholipids as reviewed in a number of articles (69–73). The information about d62-DPPC distribution obtained from our CARS images allows a better understanding of the role of cholesterol in a three-component bilayer, as discussed below.

In the DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) bilayer patches, we have shown that the Ld domain contains ∼80% DOPC and 20% d62-DPPC. This result is supported by our observation that no domains are formed in the bilayer patches when the molar percentage of d62-DPPC is below 25%. The gel domain contains ∼74% d62-DPPC and 26% DOPC, indicating that the phase segregation is induced by hydrophobic interactions that aggregate saturated lipids in the ordered gel phase.

With 10% cholesterol added to the 1:1 DOPC/d62-DPPC mixture, the domains disappear as reported before (63). As shown in Fig. 6 A, d62-DPPC is uniformly distributed in the whole bilayer on the scale of our 250-nm spatial resolution. A similar observation has been reported by Feigenson and Buboltz in the DPPC/DLPC/cholesterol GUVs (74). They suggested that a three-component bilayer at a certain level of cholesterol could form a fluid ordered phase. The fluid ordered phase provides PC molecules with a larger capacity to shield cholesterol from bulk water than the Ld phase. The  value of CD2 for the 10% cholesterol bilayer is measured as 2.29, much smaller than 8.40 (gel phase in DOPC/d62-DPPC bilayer) but higher than 0.96 (Ld phase in DOPC/d62-DPPC bilayer). This supports that the bilayer is in a fluid ordered phase.

value of CD2 for the 10% cholesterol bilayer is measured as 2.29, much smaller than 8.40 (gel phase in DOPC/d62-DPPC bilayer) but higher than 0.96 (Ld phase in DOPC/d62-DPPC bilayer). This supports that the bilayer is in a fluid ordered phase.

Interestingly, the addition of 20% cholesterol causes the formation of percolating Ld and circular Lo domains in GUVs. Our CARS data show that d62-DPPC is enriched in the Lo domain. Meanwhile, cholesterol increases the partition of d62-DPPC into the DOPC-enriched phase, with a decrease of the partition ratio between the ordered and disordered domains from 8.7 at 0% cholesterol level to 5.4 at 20% cholesterol level (see Fig. 5 B). Our observation can be interpreted as an interplay of different types of lipid-lipid interactions. On one hand, cholesterol tends to have a uniform distribution due to long-range repulsive forces (71). On the other hand, hydrophobic interactions associate cholesterol with d62-DPPC in the form of molecular complex (73).

When the level of cholesterol is increased to 30 and 40%, d62-DPPC becomes homogeneously distributed in the whole bilayer. The homogenization effect of high-level cholesterol has been qualitatively observed in fluorescence imaging studies. The whole bilayer becomes homogeneous when the cholesterol molar ratio exceeds a certain value (12,63,74), while depleting cholesterol leads to phase separation in the plasma membrane (75).

Keller and co-workers have measured the fraction of d62-DPPC in the coexisting domains using NMR spectroscopy (17). For multilamellar vesicles composed of DOPC/d62-DPPC (1:1) and 30% cholesterol at 25°C, the fraction of d62-DPPC in the Lo and Ld phases is 53 and 18%, respectively (17). This is quite different from our measurements of single bilayers shown in Fig. 5. The difference could be due to the interbilayer interactions. The domain sizes of their sample were ∼80 nm. As the authors have suggested, those nanoscale organizations could be molecular complexes instead of separate phases (17).

CONCLUSIONS

We have presented a quantitative CARS imaging method that measures the lipid composition in supported bilayers. We have shown that partition of a specific lipid between coexisting domains can be determined from the difference of the CARS intensities measured at the peak and dip frequencies of a CARS band. Our CARS images of the DOPC/d62-DPPC/cholesterol bilayer patches revealed profound interactions between cholesterol and phospholipids. The image acquisition and data analysis method reported here can be applied to quantitative vibrational imaging of weak Raman scatterers in other heterogeneous systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Liz Gamble in Hovis group and Alan Kennedy for their kind help in preparing the supported bilayers and GUVs.

This work is supported by a National Science Foundation grant (0416785-MCB).

Abbreviations used: AFM, atomic force microscopy; DOPC, dioleoyl phosphatidylcholine; DPPC, dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine; d62-DPPC, DPPC with fully deuterated acyl chains; BODIPY PC, 2-(BODIPY-3-pentanoyl)-1-hexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; CARS, coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering; GUV, giant unilamellar vesicle; SUV, small unilamellar vesicle.

References

- 1.Simons, K., and E. Ikonen. 1997. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 387:569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown, D. A., and E. London. 1998. Functions of lipid rafts in biological membranes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14:111–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edidin, M. 2003. The state of lipid rafts: from model membranes to cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 32:257–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikonen, E. 2001. Roles of lipid rafts in membrane transport. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13:470–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukherjee, S., and F. R. Maxfield. 2004. Membrane domains. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20:839–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattson, M. P. 2005. Membrane Microdomain Signaling: Lipid Rafts in Biology and Medicine. M. P. Mattson, editor. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ.

- 7.Hwang, J., L. K. Tamm, C. Böhm, T. S. Ramalingam, E. Betzig, and M. Edidin. 1995. Nanoscale complexity of phospholipid monolayers investigated by near-field scanning optical microscopy. Science. 270:610–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich, C., L. A. Bagatolli, Z. N. Volovyk, N. L. Thompson, M. Levi, K. Jacobson, and E. Gratton. 2000. Lipid rafts reconstituted in model membranes. Biophys. J. 80:1417–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietrich, C., Z. N. Volovyk, M. Levi, N. L. Thompson, and K. Jacobson. 2001. Partitioning of Thy-1, GM1, and cross-linked phospholipid analogs into lipid rafts reconstituted in supported model membrane monolayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:10642–10647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McConnell, H. M., and M. Vrljic. 2003. Liquid-liquid immiscibility in membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 32:469–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korlach, J., P. Schwille, W. W. Webb, and G. W. Feigenson. 1999. Characterization of lipid bilayer phases by confocal microscopy and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:8461–8466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veatch, S. L., and S. L. Keller. 2003. Separation of liquid phases in giant vesicles of ternary mixtures of phospholipids and cholesterol. Biophys. J. 85:3074–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaus, K., E. Gratton, E. P. W. Kable, A. S. Jones, I. Gelissen, L. Kritharides, and W. Jessup. 2003. Visualizing lipid structure and raft domains in living cells with two-photon microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:15554–15559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinia, H. A., and B. de Kruijff. 2001. Imaging domains in model membranes with atomic force microscopy. FEBS Lett. 504:194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tokumasu, F., A. J. Jin, G. W. Feigenson, and J. A. Dvorak. 2003. Nanoscopic lipid domain dynamics revealed by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 84:2609–2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Duyl, B. Y., D. Ganchev, V. Chupin, B. de Kruijff, and J. A. Killian. 2003. Sphingomyelin is much more effective than saturated phosphatidylcholine in excluding unsaturated phosphatidylcholine from domains formed with cholesterol. FEBS Lett. 547:101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veatch, S. L., I. V. Polozov, K. Gawrisch, and S. L. Keller. 2004. Liquid domains in vesicles by NMR and fluorescence microscopy. Biophys. J. 86:2910–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vacklin, H. P., F. Tiberg, G. Fragneto, and R. K. Thomas. 2005. Composition of supported model membranes determined by neutron reflection. Langmuir. 21:2827–2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lentz, B. R., Y. Barenholz, and T. E. Thompson. 1976. Fluorescence depolarization studies of phase transition and fluidity in phospholipid bilayers. 2. Two-component phosphatidylcholine liposomes. Biochemistry. 15:4529–4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrache, H. I., H. Gouliaev, S. Tristram-Nagle, R. Zhang, R. M. Suter, and J. F. Nagle. 1998. Interbilayer interactions from high-resolution x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. E. 57:7014–7024. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marxer, C. G., M. L. Kraft, P. K. Weber, I. D. Hutcheon, and S. G. Boxer. 2005. Supported membrane composition analysis by secondary ion mass spectrometry with high lateral resolution. Biophys. J. 88:2965–2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verma, S. P., and D. F. H. Wallach. 1984. Raman spectroscopy of lipids and biomembranes. In Biomembrane Structure and Function. D. Chapman, editor. Verlag Chemie. Basel, Switzerland. 167–198.

- 23.Levin, I. W. 1984. Vibrational spectroscopy of membrane assembles. In Advances in Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy. R. J. H. Clark and R. E. Hester, editors. Wiley Heyden. New York, NY. 1–48.

- 24.Caspers, P. J., G. W. Lucassen, and G. J. Puppels. 2003. Combined in vivo confocal Raman spectroscopy and confocal microscopy of human skin. Biophys. J. 85:572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Percot, A., and M. Lafleur. 2001. Direct observation of domains in model stratum corneum lipid mixtures by Raman microspectroscopy. Biophys. J. 81:2144–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uzunbajakava, N., A. Lenferink, Y. Kraan, E. Volokhina, G. Vrensen, J. Greve, and C. Otto. 2003. Nonresonant confocal Raman imaging of DNA and protein distribution in apoptotic cells. Biophys. J. 84:3968–3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Saux, A., J. M. Ruysschaert, and E. Goormaghtigh. 2001. Membrane molecule reorientation in an electric field recorded by attenuated total reflection Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 80:324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendelsohn, R., J. W. Brauner, and A. Gericke. 1995. External infrared reflection absorption spectrometry of monolayer films at the air-water interface. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 46:305–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holman, H. N., M. C. Martin, E. A. Blakely, K. Bjornstad, and W. R. Mckinney. 2000. IR spectroscopic characteristics of cell cycle and cell death probed by synchrotron radiation based Fourier Transform IR spectromicroscopy. Biopolymers. 57:329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng, J. X., and X. S. Xie. 2004. Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy: instrumentation, theory, and applications. J. Phys. Chem. B. 108:827–840. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levenson, M. D., and J. J. Song. 1980. Coherent Raman spectroscopy. In Coherent Nonlinear Optics: Recent Advances. M. S. Feld and V. S. Letokhov, editors. Springer-Verlag. Berlin, Germany. 293.

- 32.Shen, Y. R. 1984. The Principles of Nonlinear Optics. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY.

- 33.Duncan, M. D., J. Reintjes, and T. J. Manuccia. 1982. Scanning coherent anti-Stokes Raman microscope. Opt. Lett. 7:350–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zumbusch, A., G. R. Holtom, and X. S. Xie. 1999. Three-dimensional vibrational imaging by coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82:4142–4145. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng, J. X., A. Volkmer, L. D. Book, and X. S. Xie. 2001. An epi-detected coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (E-CARS) microscope with high spectral resolution and high sensitivity. J. Phys. Chem. B. 105:1277–1280. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volkmer, A., J. X. Cheng, and X. S. Xie. 2001. Vibrational imaging with high sensitivity via epi-detected coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87:023901. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng, J. X., L. D. Book, and X. S. Xie. 2001. Polarization coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Opt. Lett. 26:1341–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volkmer, A., L. D. Book, and X. S. Xie. 2002. Time-resolved coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy: imaging based on Raman free induction decay. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80:1505–1507. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dudovich, N., D. Oron, and Y. Silberberg. 2002. Single-pulse coherently controlled nonlinear Raman spectroscopy and microscopy. Nature. 418:512–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng, J. X., A. Volkmer, L. D. Book, and X. S. Xie. 2002. Multiplex coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microspectroscopy and study of lipid vesicles. J. Phys. Chem. 106:8493–8498. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Müller, M., and J. M. Schins. 2002. Imaging the thermodynamics state of lipid membranes with multiplex CARS microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 106:3715–3723. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng, J. X., Y. K. Jia, G. Zheng, and X. S. Xie. 2002. Laser-scanning coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy and applications to cell biology. Biophys. J. 83:502–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potma, E. O., W. P. de Boeij, P. J. van Haastert, and D. A. Wiersma. 2001. Real-time visualization of intracellular hydrodynamics in single living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:1577–1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng, J. X., S. Pautot, D. A. Weitz, and X. S. Xie. 2003. Ordering of water molecules between phospholipid bilayers visualized by coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:9826–9830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Potma, E. O., X. S. Xie, L. Muntean, J. Preusser, D. Jones, J. Ye, S. R. Leone, W. D. Hinsberg, and W. Schade. 2004. Chemical imaging of photoresists with coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. 108:1296–1301. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kennedy, A. P., J. Sutcliffe, and J. X. Cheng. 2005. Molecular composition and orientation of myelin figures characterized by coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Langmuir. 21:6478–6486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, H., Y. Fu, R. Shi, and J. X. Cheng. 2005. Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering imaging of live spinal tissues. Biophys. J. 89:581–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Potma, E. O., and X. S. Xie. 2003. Detection of single lipid bilayers in coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) microscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 34:642–650. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wurpel, G. W. H., J. M. Schins, and M. Müller. 2004. Direct measurement of chain order in single phospholipid mono- and bilayers with multiplex CARS. J. Phys. Chem. 2004:3400–3403. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Potma, E. O., and X. S. Xie. 2005. Direct visualization of lipid phase segregation in single lipid bilayers with coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Chemphyschem. 6:77–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aussenac, F., M. Tavares, and E. J. Dufourc. 2003. Cholesterol dynamics in membranes of raft composition: a molecular point of view from 2H and 31P solid-state NMR. Biochemistry. 42:1383–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Angelova, M. I., S. Soleau, P. Meleard, J. F. Faucon, and P. Bothorel. 1992. Preparation of giant vesicles by external AC electric fields. Kinetics and applications. Prog. Colloid Polym. Sci. 89:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaizuka, Y., and J. T. Groves. 2004. Structure and dynamics of supported intermembrane junctions. Biophys. J. 86:905–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cremer, P. S., and S. G. Boxer. 1999. Formation and spreading of lipid bilayers on planar glass supports. J. Phys. Chem. 103:2554–2559. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lotem, H., J. R. T. Lynch, and N. Bloembergen. 1976. Interference between Raman resonances in four-wave difference mixing. Phys. Rev. A. 14:1748–1755. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang, N., K. Florine-Casteel, G. W. Feigenson, and C. Spink. 1988. Effect of fluorophore linkage position of n-(9-anthroyloxy) fatty acids on probe distribution between coexisting gel and fluid phospholipid phases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 939:124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dahim, M., N. K. Mizuno, X. M. Li, W. E. Momsen, M. M. Momsen, and H. L. Brockman. 2002. Physical and photophysical characterization of a BODIPY phosphatidylcholine as a membrane probe. Biophys. J. 83:1511–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis, J. H. 1979. Deuterium magnetic resonance study of the gel and liquid crystalline phases of dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine. Biophys. J. 27:339–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vist, M. R., and J. H. Davis. 1990. Phase equilibrium of cholesterol/dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine mixtures: 2H nuclear magnetic resonance and differential scanning calorimetry. Biochemistry. 29:451–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Veatch, S. L., and S. L. Keller. 2002. Organization in lipid membranes containing cholesterol. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89:268101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leidy, C., T. Kaasgaard, J. H. Crowe, O. G. Mouritsen, and K. Jorgensen. 2002. Ripples and the formation of anisotropic lipid domains: imaging two-component supported double bilayers by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 83:2625–2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nagle, J. F., and S. Tristram-Nagle. 2000. Structure of lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1469:159–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scherfeld, D., N. Kahya, and P. Schwille. 2003. Lipid dynamics and domain formation in model membranes composed of ternary mixtures of unsaturated and saturated phosphatidylcholines and cholesterol. Biophys. J. 85:3758–3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kee, T. W., and M. T. Cicerone. 2004. Simple approach to one-laser, broadband coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Opt. Lett. 29:2701–2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Otto, C., A. Voroshilov, S. G. Kruglik, and J. Greve. 2001. Vibrational bands of luminescent zinc(II)-octaethylporphyrin using a polarization-sensitive “microscopic” multiplex CARS technique. J. Raman Spectrosc. 32:495–501. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ichimura, T., N. Hayazawa, M. Hashimoto, Y. Inouye, and S. Kawata. 2004. Tip-enhanced coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering for vibrational nanoimaging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92:220801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mabrey, S., P. I. Mateo, and J. M. Sturtevant. 1978. High-sensitivity scanning calorimetric study of mixtures of cholesterol with dimyristoyl-and dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholines. Biochemistry. 17:2464–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ipsen, J. H., G. Karlström, O. G. Mourtisen, H. Wennerström, and M. J. Zuckermann. 1987. Phase equilibria in the phosphatidylcholine-cholesterol system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 905:162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finegold, L., editor. 1993. Cholesterol in Membrane Models. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 70.McMullen, T., and R. N. McElhaney. 1996. Physical studies of cholesterol-phospholipid interactions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 1:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Somerharju, P., J. A. Virtanen, and K. H. Cheng. 1999. Lateral organization of membrane lipids. The superlattice view. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1440:32–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ohvo-Rekilä, H., B. Ramstedt, P. Leppimäki, and J. P. Slotte. 2002. Cholesterol interaction with phospholipids in membranes. Prog. Lipid Res. 41:66–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McConnell, H. M., and A. Radhakrishnan. 2003. Condensed complexes of cholesterol and phospholipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1610:159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feigenson, G. W., and J. T. Buboltz. 2001. Ternary phase diagram of dipalmitoyl-PC/dilauroyl-PC/cholesterol: nanoscopic domain formation driven by cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2775:2775–2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hao, M., S. Mukherjee, and F. R. Maxfield. 2001. Cholesterol depletion induces large scale domain segregation in living cell membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:13072–13077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]