Summary

After years of banishment from mainstream immunology, the notion that one subset of T cells can exert regulatory effects on other T lymphocytes is back in fashion. Recent work in knockout and transgenic mice has begun to bring molecular definition to our understanding of immunoregulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells (Treg/Th3/Tr1). The identification of the glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor family-related gene (GITR, also known as TNFRSF18) expressed on T regulatory cells might afford new therapeutic opportunities. Another possible therapeutic intervention could be the blockade of signaling through the molecular pair of tumor necrosis factor-related activation induced cytokine (TRANCE) and receptor activator of NF-[kappa]B (RANK). Based on the available evidence from experimental mouse tumor models, however, it seems that simply blocking or even eliminating T regulatory function will not be enough to manage established tumors. The challenge for immunotherapists now is to overcome immunosuppression using the knowledge gained through the understanding of T regulatory cell function.

It is now well established in the scientific literature that immunoregulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells control key aspects of immunologic tolerance to self-antigens. These cells constitutively express CD25 (interleukin [IL]-2 receptor [alpha] chain) on their surface and constitute 5%–10% of CD4+ T cells in humans and rodents (1–4). Many models show that removal of this subset of cells can accelerate diabetes in NOD mice (5) and lead to an enhanced state of auto-reactivity in a variety of tissues including the ovaries, thyroid gland, salivary glands, and the mucosal linings of the stomach and small intestine (6,7). Reconstitution of these same animals with CD4+CD25+ T cells prevents autoimmunity.

It is becoming clear that the antigens recognized by CD4+CD25+ cells are “self,” tissue-specific antigens. The selection of regulatory CD4+CD25+ cells in the thymus may be viewed as an altered negative selection (8,9), where T cell receptors (TCR) on CD4+CD25+ cells bind with high affinity to self-antigens in the thymus and are not deleted. Instead, in murine models, they emerge as potent suppressors into the periphery after day three of life. If neonatal rodents are thymectomized on day three or before, T regulatory cells never emerge and organ-specific autoimmunity is observed (10).

It is also becoming more evident that most tumor-associated antigens are self-antigens (11). In the past decade, researchers sought to find unique tumor-specific antigens; however, most were discovered to be expressed either during development or in normal adult tissue (12). With this in mind, some thought that by removing tissue-specific CD4+CD25+ cells, antitumor immunity could be enhanced (13–16).

In the current issue of the Journal of Immunotherapy, Tanaka et al. find that immunotherapy can be enhanced by depletion of CD4+CD25+ cells even in a difficult tumor model such as B16 melanoma. Although the mice eventually succumb to tumor, the authors show that the antitumor response was tumor specific. Another paper by Sutmuller et al. shows that depletion of CD4+CD25+ cells plus injection of an antibody capable of blocking cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) can enhance reactivity to known tumor-associated antigens, tyrosinase-related protein-2 (TRP-2), in B16 melanoma (17). This significant finding shows for the first time that reactivity against a self/tumor antigen can be enhanced by abrogating these regulatory mechanisms.

Antibody depletion of CD25+ cells in vivo has its disadvantages, because it can potentially deplete recently activated CD8+CD25+ effector cells. Sutmuller et al. show that depleting CD25+ cells in pre-vaccinated mice decreases the efficacy of treatment versus treating before vaccination (17). Similar results have been confirmed by unpublished data from our laboratory. Tanaka et al. also show that the CD4+CD25+ cells that emerge after an initial depletion with 0.4 mg of PC61 Ab (Rat antimouse CD25; IgG1) are resistant to subsequent depletions. It is possible that these mice may have become resistant to depletion because they were immunized by unpurified ascites. Such a preparation could be more immunogenic than purified material. Onizuka et al. have shown that by repeated depletions of CD4+CD25+ cells with 2.0 mg of purified PC61 antibody every other day, mice developed autoimmune disease after 1 month (13), potentially indicating that there was no resistance to multiple depletions. If the reemerged cells are truly different from the original population, then functional studies of these cells could provide additional information.

A possible way around this predicament may lie in pre-depleting CD4+CD25+ cells before adoptive cell transfer. Tanaka et al. approach this by using tumor draining lymph node cells that have been pre-depleted of CD4+CD25+ cells and then activated ex vivo. This maneuver enhances proliferation by two–three folds, although it does not result in an improvement in therapeutic efficacy. This practical approach could be applied to tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) from patients with melanoma. Recently, acquired TIL could be pre-depleted of CD4+CD25+ cells and expanded with anti-CD3/IL-2 or specific peptides from melanoma such as gp100, MART1, TRP-1, TRP-2, or tyrosinase—potentially leading to enhanced proliferation and higher reactivity against melanoma. Another alternative solution, at least in rodents, may be to use mice already deficient of CD25+ cells such as in recombinase activating gene knockout mice or nude mice. Cells of interest could then be adoptively transferred, thus, avoiding antibody-mediated depletion of effector cells.

Although CD25 seems to be a unique marker associated with these cells, it represents a poor candidate for target depletions. Another potentially more promising molecule is CTLA-4. Antibody blockade of CTLA-4 has previously been shown to augment antitumor immunity and, as mentioned above, also synergizes with CD25 depletion (17–19). Because CD4+CD25+ cells constitutively express CTLA-4 (19), some have proposed that it plays a major role in T regulatory activation, and/or in their enforcement of T cell-mediated suppression (20). However, recent evidence suggests that cells sorted from CTLA-4 knockout mice still suppress T-cell responses albeit at a lower level (19).

Based on the available evidence from experimental mouse tumor models, it seems that early therapeutic strategies designed to eliminate T cells expressing CD25 from the body will not be enough to manage established tumors. Ultimately, CD4+CD25+ cell depletion may be useful in conjunction with other therapeutic modalities. However, one side effect of depletion may be the induction of autoimmune disease. In the case of metastatic malignant melanoma, many complete responders to tumor immunotherapy develop vitiligo, an autoimmune destruction of melanocytes (11). We have found that successful therapeutic antitumor vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TRP-1) generally is accompanied by autoimmune vitiligo (21). Treatment with CTLA-4 Ab also causes autoimmune vitiligo in mice vaccinated with B16.GM-CSF (22,23). Therefore, antitumor immunity and autoimmunity are closely linked.

A potential way to avoid autoimmune disease and to protect tissues is to find the specificity of regulatory cells. Therapeutic specific regulatory cells could be transferred to protect against autoimmune disease or graft rejection (as shown in [24]). Identification of the specificity of regulatory cells has been limited, but data from many animal models suggest that tissue-specific suppression does exist and may be dependent on the continuous presence of the antigen. One such model uses the Zona Pellucida 3 (ZP3) antigen from ovarian tissue to demonstrate tissue-specific tolerance induction. Tung et al. show that the presence of the ovaries maintains tolerance to the ZP3 Ag and that upon oophorectomy tolerance is reversed (25). When CD4+CD25+ cells were sorted from male mice, they were less effective at suppression of ovarian autoimmune disease caused by day-three thymectomy than female CD4+CD25+ cells. In another model, mice expressing T cells that express a major histocompatability complex Class II-restricted TCR specific for the influenza hemagglutinin (TCR-HA) antigen were crossed with mice expressing HA in hematopoietic cells under the Ig[kappa] promoter (IG-HA). CD4+ cells from a cross between TCR-HA and IG-HA mice were tolerant to antigen in vivo (as measured by the onset of diabetes) and in vitro (as measured by antigenic stimulation). However, T cells from TCR-HA mice caused fulminant diabetes in vivo and were reactive to antigen in vitro. The CD4+ cells from the TCR-HA X IG-HA mice were anergic, IL-10 secreting cells with regulatory properties similar to that of CD4+CD25+ cells (26). This suggests that IL-10 may play a role in T regulatory function, and that antigen needs to be present to keep them activated.

In other CD4+ transgenic models, T regulatory cells appear to be the result of “leak through” of T cell receptors expressing endogenous TCR-[alpha] and -[beta] chains (27). Mice expressing the transgenic TCR for myelin basic protein rarely develop experimental autoimmune encephalitis, an experimental form of multiple sclerosis in mice, but once mice were crossed with TCR-[alpha] or -[beta] knockouts, they became more susceptible to disease. If both endogenous TCR-[alpha] and -[beta] chains were removed by crossing mice onto a recombinase activating gene deficient background, all mice developed experimental autoimmune encephalitis (28). The onset of experimental autoimmune encephalitis could be prevented by reconstituting recipient mice with CD4+ T cells from healthy mice, but only before the disease manifested. Therefore, one could speculate that the endogenous repertoire contains a population of cells that plays a role in self-tolerance induction, and for this repertoire to be active, antigen must be present. However, how these cells are activated is largely unknown.

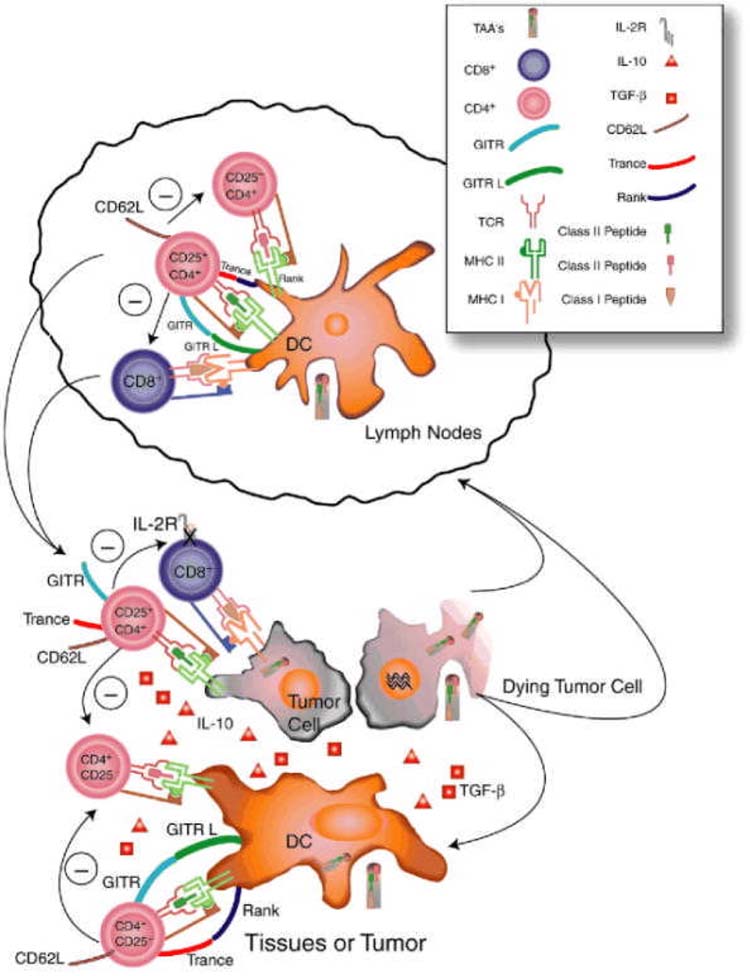

It has been postulated that the continuous presence of self-antigen activates tissue-specific regulatory cells via dendritic cells (29). In the presence of progressing tumors, tumor-associated antigens could be constitutively presented by dendritic cells to tissue regulatory cells and tumor-reactive CTL, activating the former and suppressing the latter, tipping the balance in favor of self-tolerance (Fig. 1). Recent evidence to support this hypothesis shows that regulatory cells were present in high numbers in tumors isolated from humans (30) and mouse (31). Human tumors had a high predominance of CD4+CD25+ cells as well as CD8+CD25− cells, suggesting, as Piccirillo et al. show, that IL-2R[alpha] chain is downregulated on CD8+ cells in the presence of CD4+CD25+ cells (32). In the mouse tumor model, large numbers of CD4+CD25+ cells were also found in day 20 B16 melanoma lesions and had IL-10 and TGF-[beta] mRNA in higher quantities as shown by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. When the authors looked more closely at the CD4+ TIL subsets, they found that CD4+/Th3/Tr1 TIL cells were anergic compared with CD4+/Th1 cells. Injection of recombinant IL-10 into the progressing tumor made tumors grow faster and neutralizing IL-10 with anti-IL-10 antibody slowed tumor growth. Upon adoptive cell transfer of the CD4+/Th3/Tr1 TIL cells, antitumor effect was diminished versus no treatment controls, but transfer of CD4+/Th1 TIL had the same antitumor effect as CD8+ TIL. Previously, we have shown that adoptive transfer of a CD4+ clone-specific for [beta]-galactosidase ([beta]-gal) activated endogenous CD8+ tumor-specific cells that treated [beta]-gal-expressing tumors (33). These findings support the idea that CD4+ cells can treat tumors, but that a subset of CD4+ self-regulating cells may be hindering antitumor immunity. Finding a practical way to remove CD4+ tumor-specific regulatory cells or to shut them off may be one way to prevent tolerance induction and increase antitumor immunity.

FIG. 1.

Activation of regulatory T cells. Immature dendritic cells pick up self-or tumor-associated antigens from the tissues and present them constitutively to the immune system to self-reactive tissue-specific CD4+CD25+ cells in draining lymph nodes (LN). T regulatory CD4+CD25+ cells travel continuously throughout the body via lymphatics and blood via high expression of CD62L and reactive with self-antigens. In their activating environment, they suppress any self-reactive T cell they encounter either in the LN, tissue, or tumor, keeping the suppression limited to that site. They downregulate IL-2 production in CD4+ T cells and decrease IL-2R[alpha] expression on CD8+ T cells. Suppression is mediated by cell–cell contact, but cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-[beta] may be involved. TRANCE, GITR, and other unknown molecules are upregulated and involved in T regulatory function.

Recently, two molecules have been identified on these cells that may be involved in their activation and regulation (Fig. 1). The first molecule, glucocorticoid induced TNF receptor family-related gene (GITR, also known as TNFRSF18) has been described on these cells. Stimulating GITR through an activating antibody reversed induction of suppression (34,35). The second, TNF-related activation induced cytokine (TRANCE) and receptor activator of NF-[kappa]B (RANK) has been shown to be involved in activating signaling pathways in CD4+CD25+ cells (36). Blockade of this molecular pair caused a decrease in frequency of these cells in pancreatic lymph node cells, which lead to a rapid onset of diabetes (36). It would be interesting to see what effect these antibodies have on tumor management, because activating GITR and blocking TRANCE-RANK interactions leads to autoimmunity. Finding ways to interrupt these interactions may allow turning on or off T regulatory cells at will.

The vision for immunotherapy of tumors then depends on disrupting the processes that activate immunosuppression. From previous studies, we know that we can activate tumor-specific CTL and that certain tumors are amenable to treatment with IL-2 or immunization with peptides made from tumor-associated antigens (11). Most of these studies involved CD8+ cells with relatively little focus on the CD4+ T-cell population. As seen in the literature recently, this population is more complex than previously thought. Originally Th0/Th1/Th2 and memory phenotypes were used to describe the different properties of CD4+ T cells. Eventually, Th3 (37) emerged, and finally, Tr1 or CD4+CD25+ cells have become the new family member, once thought not to exist. Because immunotherapy can work, knowing the role of CD4+ T cells, their antigens, and how they orchestrate and enhance CD8+ CTL function will help us understand the mechanisms involved in tumor establishment and maintenance as well as how to invoke potent antitumor immunity without autoimmunity. The future may lie in discovering ways to circumvent immunosuppression by tumors, regardless of how it is maintained, to tip the balance towards effective antitumor immunity.

References

- 1.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, et al. Immunological self-tolerance maintained by activated T-cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chain (CD25): breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune-diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–64. [Context Link] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suri-Payer E, Amar AZ, Thornton AM, et al. CD4+CD25+ T cells inhibit both the induction and effector function of autoreactive T cells and represent a unique lineage of immunoregulatory cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:1212–8. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Stassen M, et al. Identification and functional characterization of human CD4+CD25+ T cells with regulatory properties isolated from peripheral blood. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1285–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1285. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dieckmann D, Plottner H, Berchtold S, et al. Ex vivo isolation and characterization of CD4+CD25+ T cells with regulatory properties from human blood. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1303–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1303. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salomon B, Lenschow DJ, Rhee L, et al. B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 2000;12:431–40. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80195-8. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asano M, Toda M, Sakaguchi N, et al. Autoimmune disease as a consequence of developmental abnormality of a T cell subpopulation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:387–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.387. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shevach EM. Regulatory T cells in autoimmmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:423–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.423. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordan MS, Boesteanu A, Reed AJ, et al. Thymic selection of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by an agonist self-peptide. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:301–6. doi: 10.1038/86302. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pacholczyk R, Kraj P, Ignatowicz L. Peptide specificity of thymic selection of CD4+CD25+T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:613–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.613. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shevach EM. Suppressor T cells: Rebirth, function, and homeostasis. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R572–5. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00617-5. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature. 2001;411:380–4. doi: 10.1038/35077246. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Pel A, van der BP, Coulie PG, et al. Genes coding for tumor antigens recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes. Immunol Rev. 1995;145:229–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00084.x. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onizuka S, Tawara I, Shimizu J, et al. Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor alpha) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3128–33. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Sakaguchi S. Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Immunol. 1999;163:5211–8. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.North RJ, Awwad M. Elimination of cycling CD4+ suppressor T-cells with an anti-mitotic drug releases non-cycling CD8+ T-cells to cause regression of an advanced lymphoma. Immunology. 1990;71:90–5. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.North RJ. Cyclophosphamide-facilitated adoptive immunotherapy of an established tumor depends on elimination of tumor-induced suppressor T-cells. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1063–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.4.1063. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutmuller RP, van Duivenvoorde LM, van Elsas A, et al. Synergism of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and depletion of CD25+ regulatory T cells in antitumor therapy reveals alternative pathways for suppression of autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 2001;194:823–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.823. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Read S, Malmstrom V, Powrie F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25+CD4+ regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:295–302. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.295. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi T, Tagami T, Yamazaki S, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Exp Med. 2000;192:303–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.303. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambers CA, Sullivan TJ, Allison JP, et al. Lymphoproliferation in CTLA-4-deficient mice is mediated by costimulation-dependent activation of CD4+. T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:885–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80406-9. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overwijk WW, Lee DS, Surman DR, et al. Vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding a ‘self’ antigen induces autoimmune vitiligo and tumor cell destruction in mice: requirement for CD4+ T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2982–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2982. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Elsas A, Hurwitz AA, Allison JP. Combination immunotherapy of B16 melanoma using anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-producing vaccines induces rejection of subcutaneous and metastatic tumors accompanied by autoimmune depigmentation. J Exp Med. 1999;190:355–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.355. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colella TA, Bullock TN, Russell LB, et al. Self-tolerance to the murine homologue of a tyrosinase-derived melanoma antigen: implications for tumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1221–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1221. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kingsley CI, Karim M, Bushell AR, et al. CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells prevent graft rejection: CTLA-4-and IL-10-dependent immunoregulation of alloresponses. J Immunol. 2002;168:1080–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1080. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garza KM, Agersborg SS, Baker E, et al. Persistence of physiological self-antigen is required for the regulation of self-tolerance. J Immunol. 2000;164:3982–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.3982. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buer J, Lanoue A, Franzke A, et al. Interleukin 10 secretion and impaired effector function of major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted T cells anergized in vivo. J Exp Med. 1998;187:177–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.177. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olivares-Villagomez D, Wang YJ, Lafaille JJ. Regulatory CD4+ T cells expressing endogenous T cell receptor chains protect myelin basic protein-specific transgenic mice from spontaneous autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1883–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.10.1883. Bibliographic Links [Context Link] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van de Keere F, Tonegawa S. CD4+ T cells prevent spontaneous experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in anti-myelin basic protein T cell receptor transgenic [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]