Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine how accurately preventive care reported in the medical record reflects actual physician practice or competence.

DESIGN

Scoring criteria based on national guidelines were developed for 7 separate items of preventive care. The preventive care provided by randomly selected physicians was measured prospectively for each of the 7 items. Three measurement methods were used for comparison: (1) the abstracted medical record from a standardized patient (SP) visit; (2) explicit reports of physician practice during those visits from the SPs, who were actors trained to present undetected as patients; and (3) physician responses to written case scenarios (vignettes) identical to the SP presentations.

SETTING

The general medicine primary care clinics of two university-affiliated VA medical centers.

PARTICIPANTS

Twenty randomly selected physicians (10 at each site) from among eligible second- and third-year general internal medicine residents and attending physicians.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Physicians saw 160 SPs (8 cases × 20 physicians). We calculated the percentage of visits in which each prevention item was recorded in the chart, determined the marginal percentage improvement of SP checklists and vignettes over chart abstraction alone, and compared the three methods using an analysis-of-variance model. We found that chart abstraction underestimated overall prevention compliance by 16% (P < .01) compared with SP checklists. Chart abstraction scores were lower than SP checklists for all seven items and lower than vignettes for four items. The marginal percentage improvement of SP checklists and vignettes to performance as measured by chart abstraction was significant for all seven prevention items and raised the overall prevention scores from 46% to 72% (P < .0001).

CONCLUSIONS

These data indicate that physicians perform more preventive care than they report in the medical record. Thus, benchmarks of preventive care by individual physicians and institutions that rely solely on the medical record may be misleading, at best.

Keywords: compliance, preventive care guidelines, physician practice

It is widely accepted that preventive care is an effective strategy to promote health and a priority intervention that should be made available to everyone. The benefits of prevention—reduced morbidity and mortality—depend upon changing patient behavior and on early intervention to detect disease.1,2 Because physicians are uniquely positioned to perform clinical preventive care by virtue of their training and special access to the population,3 patients and payers expect them not only to provide such care but also to document the delivery of preventive services. The Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) has taken the initiative in these data collection efforts, developing explicit criteria and prescribing data-gathering methods to ascertain the compliance of providers and organizations with performance standards.4,5 The National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) has likewise incorporated measures of prevention in its health employer data and information set (HEDIS) measures as indicators of quality.6

Despite the recognized importance of capturing preventive services provided by physicians, the unanswered question is, how can such activity best be measured? Chart abstraction has been the method of choice for assessing preventive care and has been relied upon by agencies such as HCFA and NCQA.7–10 However, chart abstraction is expensive to perform and, importantly, subject to false negative results because of recording bias (physicians may not write down all they do) or incomplete, illegible, or unavailable medical records.5 Recording bias, in particular, may contribute to the high false negative rate in capturing quality of care.11 Claims data may be also used to document prevention but likewise lack sensitivity and tend not to capture the texture and richness of the process of care, particularly of process elements which do not result in a claim.11 An alternative approach is to survey patients, who offer a comparatively inexpensive source of information regarding technical quality of care, including delivery of preventive services.12 Patient-focused surveys to measure preventive care show excellent measurement properties and have recently been used by the VA to report compliance with prevention standards.13

Studies using chart abstraction to measure the quality of preventive care consistently show disappointing physician performance.14–16 In audits of medical records, physicians perform not only below externally developed criteria but also below criteria they set for themselves.14 This pattern has been explained in terms of lack of knowledge on the part of physicians, conflict over the content of guidelines, or inadequate time to perform preventive care.17 However, if charts are subject to recording bias, the actual practices of physicians may be better than the data suggest. Faulty data capture may contribute substantially to this apparent performance gap.18

This study evaluated the effectiveness of chart abstraction to measure the provision of clinical preventive services by physicians. We conducted a prospective assessment by randomly selecting general internists from two primary care outpatient clinics. Experienced actor patients presented unannounced at the two clinics and reported on the process of care they received, including administration of seven clinical preventive services focused on health-related behaviors. Our analysis makes a comparison between physicians' chart records from those visits, reports by the standardized patients (SPs), and physicians' responses to clinical vignettes.

We also compared chart abstraction with patient self-reports of preventive care from a representative sample of the corresponding patient population at both sites. In addition, we present a framework for conceptualizing the gap between evidence-based standards for providing preventive care and physicians' documented performance.

METHODS

Data for these comparisons were obtained from two sources: (1) primary data collected prospectively in the outpatient clinics of two VA medical centers, and (2) self-reports of preventive care from representative patient surveys previously administered at the two study sites.

Primary Data

Primary data were collected in the general internal medicine primary care clinics of two urban VA medical centers between December 1996 and August 1997. All second- and third-year residents and attending physicians assigned to these clinics were eligible to participate in the study. Informed consent was obtained, and 97% of eligible physicians agreed to participate (three refusals).

From these subjects, we randomly selected 20 physicians (10 at each site). The probability of selection was proportional to the number of physicians at each level of training in the pool of consenting subjects, yielding a total sample of 6 attending faculty, 7 second-year residents, and 7 third-year residents. We then used three methods to obtain data on preventive care provided by these physicians: (1) structured reports by SPs who presented unannounced to the physicians' clinics; (2) the medical records generated from these visits; and (3) written case scenarios (vignettes) identical in content to the clinical presentations of the SPs. The SP checklists were the gold standard measurement.

Preventive care scoring criteria were developed from national guidelines and a modified Delphi technique, generating seven preventive care items: tobacco screening, advice regarding smoking cessation (all cases were smokers), past performance of prevention measures (immunization and cancer screening), alcohol screening, diet evaluation, assessment of exercise, and counseling on physical activity. The scoring criteria were designed to be inclusive (i.e., set at thresholds that were not too restrictive). For example, credit was given for alcohol screening if the physician asked specifically about whether the patient drinks, not whether frequency was assessed or the CAGE protocol was observed.

We recruited 27 experienced actors to serve as SPs. They were trained by university-based educators to simulate one of four common conditions (low back pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes) and to complete a checklist, which included preventive care criteria, immediately following the visit. Standardized patient scripts also included details necessary for the realistic portrayal of a veteran, such as branch, duration, and location of military service. To assure the reliability of the SPs, we videotaped training sessions, compared SP scores with those of the coordinator, and arranged visits by the SPs with physician members of the research team, according to established practices for SP patient training.19–23

The SPs presented unannounced to scheduled appointments with physician subjects for initial primary care evaluations. Blinded to the identity of the patients as actors, physicians in these settings assumed responsibility for the longitudinal care of the patients, including preventive care. On average, study physicians saw one or two actor patients per month during regularly scheduled continuity clinic sessions. After each visit, the SP completed a checklist indicating the physician's performance on the seven preventive care items. Charts generated at each SP visit were retrieved from the clinic and abstracted by an expert nurse abstractor to generate scores for the same seven items.

We also gave the physicians clinical vignettes designed to recreate the sequence of a typical patient visit. First, the physicians were given the presenting problem and asked to provide open-ended responses identifying the most relevant history questions to be asked. A similar stepwise process was repeated for the physical examination, diagnostic testing, and finally the treatment plan. Since new information was provided at each stage, physicians were not allowed to go backward to modify their responses to previously completed stages of the vignette. The information presented in the vignettes corresponded exactly to the clinical presentations of the SPs. The same nurse abstractor then scored physicians' responses to the vignettes using the same explicit quality criteria that were in the SP checklist and the chart abstraction form.24,25

Physician subjects completed 160 evaluations of SPs (8 cases × 20 physicians). Initial visits occurred more than 3 months after informed consent was given to diminish physician recall of the study at the time of its onset and minimize actor patient detection. In only five instances were SPs detected by providers.

Secondary Data

We used existing data from the Veterans Health Survey, performed annually by the VA National Center for Health Promotion for the purpose of reporting to Congress the rates of health promotion and disease prevention services delivered to veterans. The Veterans Health Survey includes self-reports by patients of the preventive care given by their providers over the course of a year; for our study, data from fiscal year 1997 (October 1996 through September 1997) was used. All patients enrolled in primary care clinics were eligible for participation. For each VA facility, questionnaires were mailed to a random sample of 300 men and 150 women; an overall response rate of 67% was achieved. Three measures—advice regarding smoking cessation, alcohol screening, and activity counseling—were available from both of our study sites for the purpose of comparison. Comparisons were made between the scores provided by patients and the primary data from SP checklists to evaluate the face validity of our findings.

Analysis

Using the primary data, six to seven preventive care items were scored for each of the 160 physician patient visits. To generate percentile scores for each method, we calculated the percentage of visits in which the prevention practice occurred. We also calculated the marginal percentile improvement of SP checklists and vignettes over the chart abstraction score alone. Comparison between methods was done using a 3-way analysis-of-variance (ANOVA) model, which accounted for the design of the experiment. Two-way comparisons between methods used the Student-Neuman-Keuls method, which accommodates multiple comparisons and adjusts the pairwise significance accordingly. For the marginal contribution of SPs and vignettes to the chart abstraction scores, a 1-way ANOVA was performed comparing (chart) to (chart + SP) to (chart + SP + vignette). This model was used for descriptive purposes because the groups are not independent of one another.

In addition, we compared scores by site and by training level of subjects (second postgraduate year, third postgraduate year, attending) using the aforementioned ANOVA model along with the Student-Neuman-Keuls procedure to subanalyze significant main effects.

The statistical significance of the difference in mean scores between SP scores and Veterans Health Survey scores for each site was calculated by means of a 2-tailed t test.

RESULTS

Relative to our gold standard of SP checklists, medical record abstraction underestimated overall compliance with preventive measures by 16%(Table 1). Total chart abstraction scores for the seven prevention items (45.8% ± 14.4%) were lower than scores for both SPs (61.7% ± 12.9%) and clinical vignettes (48.3% ± 10.4%), although the difference between chart scores and vignettes was not significant.

Table 1.

Scores by Prevention Item for Chart Abstraction, Standardized Patient Checklists, and Vignettes

| Preventive Measure | Chart Abstraction* | Standardized Patient Checklists* | Vignettes* | P Value† | % Difference (Checklist-Chart) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco screening | 93.1 ± 12.5 | 94.4 ± 9.5 | 90.0 ± 13.8 | .36 | 1.3 |

| Advice regarding smoking cessation | 41.3 ± 28.4 | 60.6 ± 24.8 | 35.6 ± 15.9 | <.01 | 19.3 |

| Past performance of prevention measures | 43.8 ± 35.5 | 65.0 ± 25.5 | 1.9 ± 4.6 | <.01 | 21.2 |

| Alcohol screening | 72.5 ± 31.3 | 85.6 ± 21.9 | 75.0 ± 24.7 | .11 | 13.1 |

| Diet evaluation | 23.1 ± 15.9 | 35.0 ± 18.0 | 39.4 ± 20.8 | .02 | 11.9 |

| Assessment of exercise | 29.4 ± 14.2 | 56.3 ± 22.4 | 47.5 ± 28.3 | <.01 | 26.9 |

| Activity counseling | 17.5 ± 20.0 | 35.0 ± 22.1 | 48.8 ± 32.9 | <.01 | 17.5 |

| Total | 45.8 ± 14.4 | 61.7 ± 12.9 | 48.3 ± 10.4 | <.01 | 15.9 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation.

P values from 3-way analysis of variance comparing methods.

Chart abstraction underestimated compliance with preventive measures for all seven items when compared with SPs and for four items when compared with vignettes. For example, an assessment of exercise was reported in 56% of encounters by the actor patient and 48% of encounters by vignettes, but only 29% of encounters by chart abstraction. Percentage differences across the three methods were significant for five of seven individual prevention items and for the total of all items.

In a pairwise comparison between methods, SPs were consistently highest or statistically not significantly different from the other methods for the seven prevention items (Table 2). For all but one measure (past performance of prevention measures), vignettes were also superior to or no different from chart abstraction.

Table 2.

Ranking of Methods Across Prevention Items*

| Preventive Measure | Ranking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco screening | SP | = | Vignette | = | Chart |

| Advice regarding smoking cessation | SP | > | Vignette | = | Chart |

| Past performance of prevention measures | SP | > | Chart | > | Vignette |

| Alcohol screening | SP | = | Vignette | = | Chart |

| Diet evaluation | SP | = | Vignette | > | Chart |

| Assessment of excercise | SP | = | Vignette | > | Chart |

| Activity counseling | SP | = | Vignette | > | Chart |

| Total | SP | > | Vignette | = | Chart |

Two-way comparisons using Student-Neuman-Keuls method (P < .05). SP indicates standardized patient.

The marginal contribution of SP checklists and vignettes to performance as measured by chart abstraction was significant for all seven prevention items (Fig. 1). Each bar in Figure 1 is the composite of three components. The lowest shaded region of each bar is the score for chart abstraction alone; the middle region represents the addition, or marginal contribution, to the score when the SP checklist and chart abstraction are combined; and the upper region represents the increment when all three methods were combined. For example, the addition of checklist data increased the score for exercise assessment from 29% (chart abstraction alone) to 60%. The addition of vignettes further raised the score to 75% (P < .0001). Overall, the addition of the SP checklist and vignettes increased prevention scores from 46% to 72% (P < .0001).

FIGURE 1.

Marginal contribution of standardized patient checklists and vignettes to chart abstraction.

Significant differences between methods persisted when prevention scores were evaluated by site (Table 3). At both sites, the SP scores were superior to or not different from the scores for both vignettes and chart abstraction. Further, we observe a consistent difference in the performance of site A relative to site B, a difference seen across methods. When these data were analyzed by training level, the SP scores were again higher than charts or vignettes for each training level, although not all differences were statistically significant. Interestingly, no clear correlation between average score and training level was demonstrated.

Table 3.

Prevention Scores by Site and Physician Training Level

| Site | Physician Training Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | PGY-2 | PGY-3 | Attending | |

| Chart abstraction* | 56.4 ± 9.0 | 35.1 ± 10.4 | 49.3 ± 9.2 | 42.4 ± 14.2 | 45.5 ± 20.4 |

| SPs* | 70.3 ± 9.3 | 53.2 ± 10.2 | 63.4 ± 8.9 | 57.4 ± 16.7 | 64.8 ± 12.8 |

| Vignettes* | 49.6 ± 11.9 | 46.7 ± 9.0 | 42.3 ± 12.7 | 54.4 ± 5.3 | 47.7 ± 8.8 |

| P value† | .0004 | .001 | .004 | .10 | .08 |

| Ranking‡ | SP > vignette = | SP = vignette > | SP > vignette = | SP = vignette = | SP = vignette = |

| chart | chart | chart | chart | chart | |

Values are mean ± standard deviation.

P values from one-way analysis of variance comparing the three methods.

Two-way comparisons using Student-Neuman-Keuls method ( P < .05).

PGY-2 indicates postgraduate year 2; PGY-3, postgraduate year 3; SP, standardized patient.

We also compared the SP scores for three prevention items with self-reports by patients from the study sites (Table 4). For two of the prevention items (counseling on physical activity and advice regarding smoking cessation), patients reported more prevention services than did SPs at both sites. For example, patients reported receiving activity counseling in 60% of cases at site A and 64% of cases at site B, compared with SP scores of 40% (site A) and 30% (site B). Conversely, less alcohol screening was reported by patients at both sites compared with the alcohol screening reported by SPs.

Table 4.

Comparison of Standardized Patients to Veterans Health Survey

| Site A | Site B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preventive Measure | Standardized Patient Checklist, % | Veterans Health Survey, % | Standardized Patient Checklist, % | Veterans Health Survey, % |

| Advice regarding smoking cessation | 75 | 77 | 46* | 69* |

| Alcohol screening | 94* | 31* | 78* | 27* |

| Activity counseling | 40† | 58† | 30* | 64* |

P < .05.

P < .01.

DISCUSSION

These data indicate that physicians perform more clinical preventive services than they report in the medical record. Compared with chart abstraction, the gold standard measurement of SP checklists captured significantly more preventive care during clinical encounters, with the difference ranging from 12% to 26% for six of the seven measured items. Considered alone, the medical record seriously underestimated the actual quality of preventive services rendered by physician subjects. Recording bias made an important contribution to the performance gap of subject physicians, a bias previously observed for other elements of care.11,24

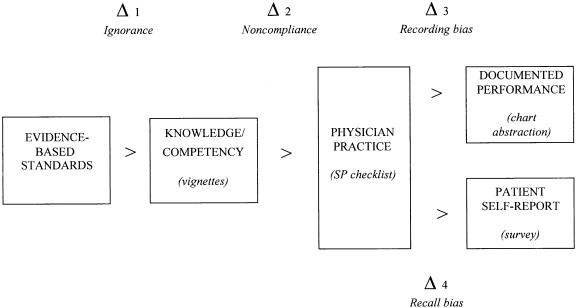

We developed a conceptual framework to understand the sources of the differences we observed between measurement methods and, more broadly, to explain the gap between desired performance of preventive care according to evidence-based guidelines and documented performance as captured by chart abstraction (Fig. 2). Physician practice—the actual encounter directly recorded by our SPs—is the key event that triggers a change in patient behavior. Provider practice is based on evidence standards that the physician knows or has learned. Patient self-reports and written clinical notes by contrast come after practice.

FIGURE 2.

Conceptualization of the prevention-performance gap.

The first difference occurs when the expectation according to evidence-based standards (e.g., those found in guidelines) exceeds the clinician's competency, which we define as knowledge (Δ1). A second occurs between the clinician's knowledge and actual practice (Δ2). This may result from time constraints, environmental concerns (e.g., lack of privacy), or organizational issues that lead to noncompliance with recommended practices. The final difference between actual practice and observed or documented performance is attributable to recording bias, chart illegibility, or other factors that produce false negatives (Δ3).

A parallel gap between actual practice and self-reporting involves the patient (Δ4). When the physician performs a prevention measure in clinical practice, the patient reports receiving less service because of recall bias (Δ4), just as the physician may record less than is performed because of recording bias (Δ3). This gap (Δ4) is critical, because the patient's failure to retain advice or counseling inevitably inhibits the behavior change required to improve health outcomes.

We observed all these gaps in our study. The magnitude of the recording bias (Δ3) (i.e., the marginal contribution of the SP checklist score to the chart abstraction score) was 17% overall. The addition of vignettes added 9% to the overall score, reflecting areas in which competency exceeded practice (Δ2). Together, correction of noncompliance (Δ2) and recording bias (Δ3) would have added at least 26% to the score of physician subjects in this study. The magnitude of reporting bias on the part of patients (Δ4) is not measured precisely in this study; however, our comparison of chart abstraction with patient self-reports suggests the possibility that such bias may also be important to consider.

This conceptualization suggests a broader approach to correcting the poor performance of clinical preventive services than evaluations based solely on misleading record reviews. Achieving expectations for the delivery of preventive care requires targeted strategies to correct each performance gap: education to improve the knowledge of physicians (Δ1), quality improvement efforts and practice support to enhance compliance with explicit standards (Δ2), and, as highlighted by these results, development of alternatives to chart abstraction that more accurately capture prevention services (Δ3). Minimal effort has been given to improving data capture despite the growing awareness of the recording bias inherent in chart abstraction. We must return to the question asked at the outset: How should we measure the provision of preventive care?

Standardized patient checklists, our gold standard method, provide reliable measurement of clinical practice but are expensive and impractical for routine use. Conversely, surveys of actual patients are a comparatively inexpensive and potentially rich source of information on the process of care, including health promotion and disease prevention.12 In our study, such data showed higher rates of preventive care than standardized patients for two of three available measures. The benefits of this approach include patients' ability to integrate services rendered over time by multiple providers or different members of multidisciplinary care teams, a perspective not available from analysis of single encounters.17,26 Patient self-reports may also capture information not readily abstracted from the medical record, such as behavioral counseling and education. Perhaps most important, self-reports of health behavioral interventions serve as relevant indicators of the effective delivery of health messages.12

Clinical vignettes may also be a useful way to measure the quality of preventive care. In our study, vignettes were comparable, if not superior, to charts for measuring such care. Vignettes are also responsive to actual differences in quality, as seen between sites in our data. A relatively inexpensive method, vignettes also provide a case-mix–controlled method for measuring preventive care provided by individuals or groups of physicians.24

Claims data are useful in documenting other kinds of preventive care, such as imaging studies (e.g., mammography for breast cancer screening), laboratory tests (e.g., low-density lipoprotein cholesterol measurement), or medications (e.g., β-blockers for coronary artery disease).26 The development of electronic versions of the medical record may resolve certain limitations of charts, including illegibility and unavailability.27 However, the electronic medical record is still subject to recording bias for preventive care or counseling that does not result in immediate medication prescriptions or orders for tests or imaging studies.28

The development of new measurement methods must also take into consideration the role of organizational factors in the delivery of clinical preventive services. Our study examined individual provider behavior, which we believe to be central to this process. However, the observed underperformance of preventive measures may relate to dynamics common to the institutions participating in this evaluation, such as the quality of ancillary support or time constraints. Further research is needed to determine the interactions between individual provider performance of prevention on the one hand and systems level variables on the other. Also, additional evaluations are needed to determine if these results generalize to other settings.

In summary, chart abstraction, the current standard method of measuring preventive care, seriously underestimates the quality of care being delivered by physicians. Benchmarks of individual and institutional performance that rely solely on the medical record are misleading, at best. Efforts to improve the delivery of preventive care must focus on enhancing physician knowledge and performance while recognizing that medical records do not always capture adequate practice. To improve the measurement of preventive care delivery, alternative strategies, such as clinical vignettes, should be used more widely.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Steven Asch and Leonard Kleinman for their helpful comments on the draft manuscript.

Dr. Peabody is supported by an Advanced Research Career Development Award for the Health Services Research and Development Service in the Department of Veterans Affairs.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGinnis JM, Lee PR. Healthy people 2000 at mid decade. JAMA. 1995;273:1123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson V, Marano MA. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1994. Vital Health Statistics 10 (189). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Audet AM, Scott HD. The uniform clinical data set: an evaluation of the proposed national database for Medicare's quality review program. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:1209–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-12-199312150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawthers AG, Palmer RH, Edwards JE, et al. Developing and evaluating performance measures for ambulatory care quality: a preliminary report of the DEMPAQ project. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1993;19:552–65. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGlynn EA. Six challenges in measuring the quality of health care. Health Aff. 1997;16:7–21. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leshan LA, Fitzsimmons M, Marbella A, Gottlieb M. Increasing clinical prevention efforts in a family practice residency program through CQI methods. Jt Comm Qual Improv. 1997;23:391–400. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanazaro PJ, Worth RM. Measuring clinical performance of individual internists in office and hospital practice. Med Care. 1985;23:1097–114. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietrich AJ, Goldberg H. Preventive content of adult primary care: do generalists and subspecialists differ? Am J Public Health. 1984;74:223–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.3.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey TS, Levis D, Pickard CG, Bernstein J. Development of a model quality-of-care assessment program for adult preventive care in rural medical practices. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1991;17:54–9. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garnick DW, Fowles J, Lawthers AG, et al. Focus on quality: profiling physicians' practice patterns. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 1994;17:44–75. doi: 10.1097/00004479-199407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies AR, Ware JE. Involving consumers in quality of care assessment. Health Aff. 1988;7(1):33–48. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.7.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36:728–39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woo B, Woo B, Cook EF, Weisberg M, Goldman L. Screening procedures in the asymptomatic adult: comparison of physicians' recommendations, patients' desires, published guidelines, and actual practice. JAMA. 1985;254:1480–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.254.11.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romm FJ, Fletcher SW, Hulks BS. The periodic health examination: comparison of recommendations and internists' performance. South Med J. 1981;74:265–71. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McPhee SJ, Richard RJ, Solkowitz SN. Performance of cancer screening in a university general internal medicine practice: comparison with the 1980 American Cancer Society Guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 1986;1:275–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02596202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hershey CO, Karuza J. Assessment of preventive health care. Design considerations. Prev Med. 1997;26:59–67. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawthers AG, Palmer RH, Banks N, Garnick DW, Fowles J, Weiner JP. Designing and using measures of quality based on physician office records. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 1995;18:56–72. doi: 10.1097/00004479-199501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beullens J, Rethans JJ, Goedhuys J, Buntinx F. The use of standardized patients in research in general practice. Fam Pract. 1997;14:58–62. doi: 10.1093/fampra/14.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vu NV, Marcy MM, Colliver JA, Verhulst SJ, Travis TA, Barrows HS. Standardized (simulated) patients' accuracy in recording clinical performance check-list items. Med Educ. 1992;26:99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1992.tb00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz MH, Colliver JA. Using standardized patients for assessing clinical performance: an overview. Mt Sinai J Med. 1996;63:241–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrell BG. Clinical performance assessment using standardized patients. A primer. Special series: core concepts in family medicine education. Fam Med. 1995;27:14–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinnersley P, Pill R. Potential of using simulated patients to study the performance of general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43:297–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of three methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283:1715–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luck J, Peabody JW, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M, Glassman P. How well does chart abstraction measure quality? A prospective comparison of quality between standardized patients and the medical record. Am J Med. 2000;108:642–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerbert B, Hargreaves WA. Measuring physician behavior. Med Care. 1986;24:838. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198609000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bates DW, Pappius E, Kuperman GJ, et al. Using information systems to measure and improve quality. Int J Med Inf. 1999;53:115–24. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(98)00152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bates DW, Kuperman G, Teich JM. Computerized physician order entry and quality of care. Quality Manag Health Care. 1994;2:18–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]