Abstract

Objective:

To discuss the association between 2 unreported episodes of head trauma and an acute subdural hematoma in a high school football player; to address the role of the sport health care team in secondary schools when caring for an athlete with head trauma; and to recognize the importance of educating athletes and coaches about this condition.

Background:

A previously healthy athlete experienced 2 unreported episodes of head trauma during a single game. The athlete was conscious and oriented to person, time, and place, but he vomited and complained of severe headache, nausea, and vertigo. During transfer, the athlete appeared to have a seizure.

Differential Diagnosis:

Subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, intracerebral hemorrhage, second-impact syndrome, cervical spine injury, or epilepsy.

Treatment:

Computed tomography scan indicated fluid over the left frontal temporal fossa. Conservative treatment was begun, and the fluid resolved without incident.

Uniqueness:

A single episode of blunt trauma has been thought to cause an acute subdural hematoma. However, multiple concussions can also result in this condition.

Conclusion:

Single or multiple episodes of head trauma can lead to an acute subdural hematoma. This case study reflects the importance of proper education in the recognition and care of head trauma and return-to-play guidelines for athletes and coaches. A sport health care team in all secondary schools can provide the immediate and appropriate intervention for such injuries.

Keywords: second-impact syndrome, head injury, concussion, seizure

In football alone, an estimated 1 in 5 high school athletes will experience a concussion each year. Overall, 250 000 concussions are observed in football, with head injuries being the leading cause of death in sports.1 In 2000, the National Collegiate Athletic Association2 reported a continuing increase in the concussion rate, which was significantly higher by 4.2% than previous averages. In a 3-year study of mild traumatic brain injury of 10 high school sports by Powell and Barber-Foss,3 football accounted for the highest proportion of such injuries (63.4%).

In general, a concussion can be defined as a traumatic alteration in mental status, commonly followed by confusion and amnesia.4 Severe head impact occurs with a concussion, and an individual may develop or be predisposed to severe traumatic brain injury, such as a cerebral, epidural, or subdural hematoma, which is a medical emergency.5 Second-impact syndrome, a subsequent and possibly fatal brain injury that can occur when a second head injury is received before the initial head injury has resolved, can be associated with a concussion. This syndrome is important because an athlete may present with a seemingly mild concussion; however, within seconds, the athlete may develop symptoms of second-impact syndrome. Second-impact syndrome has a mortality rate of up to 50%,6 and therefore, it must be prevented whenever possible and recognized early when it occurs.

In 1984, Albright7 reported 16 intracranial hematomas in high school football athletes, leading to 6 deaths. The most common cause of head injury death is a subdural hematoma, which results most often from a rupture of the veins in the subdural space, leading to slow venous bleeding between the dura and brain parenchyma. If the parenchyma is ruptured, arterial bleeding may also contribute to this pathologic condition.8,9 Between 1984 and 1988, the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research10 reported 18 incidences of subdural hematomas in athletes at various levels of football.

A football player who has received a minor head injury is 4 times as likely to sustain a subsequent head injury.1 The following case study reveals how 2 unreported episodes of head trauma can lead to a subdural hematoma, a potentially life-threatening head injury.

CASE REPORT

The patient was an 18-year-old high school football player, with an unremarkable medical history, who was 181 cm tall and weighed 84 kg. While walking toward the sideline, the athlete took off his helmet and appeared confused. Falling to his knees, he began to vomit. However, the patient was oriented to time, person, and place. His immediate complaints included severe head pain, nausea, and vertigo. No neck pain or any lower or upper extremity paresthesias were present.

The specific head injury or head contact that precipitated this event could not be identified. However, the athlete recalled being hit on 2 separate occasions during the game, although he did not report the incidents to the coaching staff or certified athletic trainer. The patient stated that he had a headache and nausea, but he continued to participate in the game.

To prevent a catastrophic outcome, even though loss of consciousness was not witnessed, paramedics were summoned on the field for transfer because of the patient's 2 unreported episodes of head trauma and symptoms associated with a concussion. While he was being prepared for transfer, the patient's level of consciousness decreased, and he became less responsive. The neck was stabilized with a cervical collar to prevent further injury, although there was no cervical spine tenderness, and the patient appeared to have a mild seizure, becoming temporarily unresponsive to stimuli. In the ambulance during transport, the patient had a witnessed seizure and was incontinent of urine. Attempts to intubate him were unsuccessful due to his resistance.

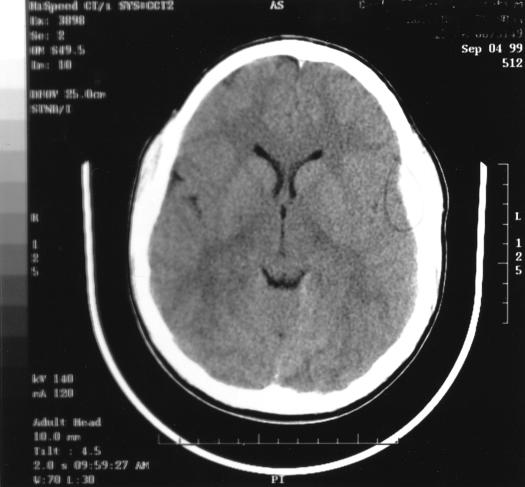

On arrival at the emergency department, the athlete was oriented to time, person, and place. He complained of severe headache, nausea, and retching. He denied any neck or back pain or paresthesias. Mannitol, 80 g, was given to reduce intracranial pressure. The neurologic examination revealed a Glasgow coma scale score of 15. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. No nystagmus or periorbital or retroauricular ecchymosis existed, and extraocular function was intact. Reflexes and sensation were normal. Cervical, thoracic, and lumbosacral x-ray films were normal. An immediate computed tomographic (CT) scan suggested a left frontal-temporal acute subdural hematoma that measured 1.2 cm, with an equivalent left-to-right shift (Figure), although the images were not particularly remarkable.

CT scan suggesting left-temporal acute subdural hematoma measuring 1.2 cm with an equivalent left-to-right shift.

The patient was given phenytoin (dosage was not stated in the patient's record) for prophylaxis of seizures, which were thought to be a possible result of the subdural bleeding. He was admitted to the surgical intensive care unit for monitoring of his neurologic status and for an additional CT scan, if his condition worsened during the night, to assess the need for neurosurgical intervention. Additional CT scans and examinations throughout the night did not indicate the need for surgical intervention. Approximately 24 hours later, the CT scan revealed a significantly smaller amount of blood than on the previous examination, with no additional subdural collections or mass effects. The athlete was released under his parents' care. He complained of a headache and inability to recall specific events involving his transport to the emergency department (anterograde amnesia). The parents were instructed not to let the patient participate in any activities, such as school or sports, until he was cleared by the physician and follow-up CT scan.

One week later, the patient returned for a follow-up CT scan and electroencephalography. The CT scan revealed that the subdural hematoma had resolved. The athlete complained of severe headache and nausea, not uncommon after such an injury. Acetaminophen was prescribed for pain and headache and trimethobenzamide for nausea (medication dosages were not stated in the patient's chart). The electroencephalogram revealed abnormal sharp waves, consistent with seizure activity, and therefore, phenytoin was prescribed for 6 months. The patient was instructed not to participate in football for the remainder of the season or drive for 6 months and was withheld from school for 2 weeks.

Twelve days after the initial head injury, the patient complained of continued headaches and nocturnal neck pain. Clinical examination by the physician revealed an area of marked tenderness that measured 1 to 2 cm in diameter beneath the left occipital protuberance and increased pain when the patient turned his head to the right. No cervical spine radiographs were taken during the evaluation. The clinical impression was a cervical ligament strain from the previous injury. A prescription for ketorolac, 10 mg/d, was given in conjunction with diazepam, 5 to 10 mg/d.

One month later, the patient was progressing well and able to increase daily activities. The nocturnal neck pain from the cervical ligament sprain had ceased. The athlete was restricted from physical education class until fully asymptomatic and cleared by the physician. He was able to complete a full day at school but still had mild headaches at the end of the day or after walking to classes and excessive activity in class. The patient's restrictions included no contact sports, such as football, for at least 1 year. However, depending on recovery, he might be able to participate in the upcoming high school baseball season with the use of special protective equipment at all times, such as a helmet, and clearance from the physician. Nonetheless, the sport health care team must make a careful decision in allowing the athlete to participate in the baseball season. Although a protective helmet would be used, requirements for participation would include sprinting, base running, and sliding, all of which could result in contact or collision.

DISCUSSION

Cantu and Mueller11 reported the number of catastrophic and fatal injuries in high school football, including head injuries, had decreased dramatically between 1982 and 1996. The authors noted 1.76 fatalities per 100 000 high school football participants, with a low of 0 in 1990.11 However, to prevent possible catastrophic outcomes, health care professionals must immediately recognize, evaluate, and manage athletes with head injuries. First, to successfully care for head injuries, both players and coaches need to understand the risks of multiple head injuries and how return-to-play guidelines guide decision making. Players often decide to return to play after a head injury without seeking medical attention. This action is at times motivated by the fear of ridicule from the coaching staff and fellow players. Also, players often are ignorant of the possible life-threatening consequences of returning to play without proper medical attention.1

Second, according to Ransone and Dunn-Bennett,12 coaches alone did not meet adequate first-aid standards in dealing with injuries and may make decisions that exceed their training. To date, sport first-aid and safety training for high school coaches is only required in 28 states.13 Certified athletic trainers can not only provide proper recognition and care of athletic injuries but also play an important liaison role among the team physician, coaches, and athletes.14

Concussions

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention15 recently reported that approximately 300 000 general sports concussions occur per year in the United States. Although no universally accepted definition of a concussion exists, this condition was previously defined as “a clinical syndrome characterized by immediate or transient posttraumatic impairment of neural function, such as alteration of consciousness and disturbance of vision or equilibrium, due to brainstem involvement.”16 However, in 1997, Kelly and Rosenberg17 concisely defined a concussion as “an alteration in mental status due to biomechanical forces that affect the brain that may or may not cause the loss of consciousness.” The hallmarks of a concussion are confusion and amnesia, although signs and symptoms vary with each individual.4 A recent study by Collins et al18 revealed that most sport-related concussions do not result in loss of consciousness. However, we must remember that loss of consciousness may be transient or missed.19

Acute Subdural Hematoma

According to Powell and Barber-Foss,3 4 cases of subdural hematomas in high school football were identified during a 3-year period. The individual with a subdural hematoma typically presents with loss of consciousness. Focal neurologic findings include pupillary asymmetry. Individuals need immediate medical attention and transport for a CT scan.20

Subdural hematoma, the most common cause of head injury death,7 can be divided into 2 categories. A simple subdural hematoma presents without cerebral contusion or edema. The mortality rate for a simple subdural hematoma is approximately 20%. The second category consists of brain contusion with hemispheric swelling or bleeding. The mortality rate for this subdural hematoma is 50%.21 Severe damage is caused by swelling or bleeding, typically due to venous rupture, which results in herniation of brain tissue and cerebral ischemia, potentially causing death.9 Although a subdural hematoma may be caused by a single incident, there are patients in whom this severe head injury resulted from repeated head injuries.9,22

Concussion Grading Scales and Return-to-Play Guidelines

Various grading and guidelines exist (Table 1),4,23–25 and confusion or miscommunication among the physician, athletic trainer, coaches, and players may occur as to when the athlete can safely return to competition.

Table 1.

Concussion Grading Scales

Our patient presented with no loss of consciousness, symptoms lasting for more than 15 minutes, confusion, and delayed posttraumatic amnesia. Interestingly, according to Cantu25 and the Colorado Medical Society,24 our patient would have been classified as having a grade I (mild) concussion. However, the American Academy of Neurology4 and Bruno et al23 would have classified him as having a grade II (moderate) concussion. Although each of these classifications is correct according to the patient's presentation, these variances reiterate the importance of establishing communication and guidelines among the sport health care team regarding recognition, evaluation, and treatment of head injuries and concussions.

In conjunction with the various concussion grading guidelines, athletes and the sport health care team must understand and comply with return-to-play guidelines4,24,25 adopted by the physician, athletic trainer, coaching staff, and athletes (Table 2). For this patient, the physician conservatively decided on no contact sports for at least 1 year. However, the patient might be able to participate in the upcoming baseball season with clearance and wearing protective equipment, such as a helmet, at all times. Nevertheless, the final decision as to when the patient may return to play is a clinical judgment by the patient's physician.4 If surgical intervention is required, such as in removal of a blood clot or posttraumatic hydrocephalus, the athlete should not be allowed to return to contact sports.25

Table 2.

Return-to-Play (RTP) Guidelines

CONCLUSION

This case report reveals how 2 unreported episodes of head trauma can be associated with an acute subdural hematoma, a potentially life-threatening condition. Although an athlete who has been unconscious may, in some instances, be able to return to play safely, an athlete who has remained conscious may, in fact, be developing a subdural hematoma or other severe traumatic brain injury.26 Loss of consciousness is used in all the current guidelines; however, Collins et al,27 using neuropsychological measures, demonstrated that the presence or absence of consciousness does not predict severity of injury.27 Although our patient sustained no distinct loss of consciousness, his severe head injury needed to be recognized and evaluated to prevent a catastrophic outcome.

Appropriate education and training for players and coaches regarding the care of head injuries is needed to prevent potentially catastrophic events. According to a recent report from the Scientific Affairs Council of the American Medical Association,14 certified athletic trainers are proposed to be present in secondary schools to provide proper recognition, care, and management of athletic injuries in conjunction with the team physician. Finally, within the sport health care team, agreement is needed before the season on which concussion grading and return-to-play guidelines will be used. Also, there should be agreement that the sport health care team will make all on-field and off-field decisions on the evaluation and treatment of head injuries. Compliance by the team physician, athletic trainer, coaching staff, and players is needed at all times to prevent catastrophic outcomes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gerberich SG, Priest JD, Boen JR, Straub CP, Maxwell RE. Concussion incidences and severity in secondary school varsity football players. Am J Public Health. 1983;73:1370–1375. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.12.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCAA News. News and features. 2000. Feb 28, Available at: www.ncaa.org. Accessed May 22, 2000.

- 3.Powell JW, Barber-Foss KD. Traumatic brain injury in high school athletes. JAMA. 1999;282:958–963. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.10.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly JP, Nichols JS, Filley CM, Lillehei KO, Rubinstein D, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Concussion in sports: guidelines for prevention of catastrophic outcomes. JAMA. 1991;266:2867–2869. doi: 10.1001/jama.266.20.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narayan RK, Willberger JE Jr, Povilishock JT, editors. Neurotrauma. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantu RC, Voy R. Second-impact syndrome: a risk in any contact sport. Physician Sportsmed. 1995;20(12):27–34. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1995.11947799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albright L American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Sports Medicine. Health Care in Young Athletes. Evanston, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1983. Head and neck injuries (revised) pp. 263–281. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson W, Gieck J, Jane J, Hawthorne P. Athletic head injuries. J Athl Train. 1984;19:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shell D, Carico GA, Patton RM. Can subdural hematoma result from repeated minor head trauma? Physician Sportsmed. 1993;21(4):74–84. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1993.11710364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller FO, Cantu RC. The annual survey of catastrophic football injuries: 1977–1988. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1991;19:261–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantu RC, Mueller FO. Fatalities and catastrophic injuries in high school and college sports, 1982–1997. Physician Sportsmed. 1999;27(8):35–48. doi: 10.3810/psm.1999.08.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ransone J, Dunn-Bennett LR. Assessment of first-aid knowledge and decision making of high school athletic coaches. J Athl Train. 1999;34:267–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Sport Education Program, National Federation of State High School Associations. Raising the Standard: The 1998 National Interscholastic Coaching Requirements Report. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyznicki JM, Riggs JA, Champion HC. Certified athletic trainers in secondary schools: report of the Scientific Affairs Council, American Medical Association. J Athl Train. 1999;34:272–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sports-related recurrent brain injuries: United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:224–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Committee on Head Injury Nomenclature of Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Glossary of head injury, including some definitions of injury to the cervical spine. Clin Neurol. 1966;12:386–394. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly JP, Rosenberg JS. Diagnosis and management of concussion in sport. Neurology. 1997;48:575–580. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins MW, Grindel SH, Lovell MR, et al. Relationship between concussion and neurophysical performance in college football players. JAMA. 1999;282:964–970. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.10.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sturmi JE, Smith C, Lombardo JA. Mild brain trauma in sports: diagnosis and treatment guidelines. Sports Med. 1998;25:351–358. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199825060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warren WL, Jr, Bailes JE. On field evaluation of head injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1998;17:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torg JS. Athletic Injuries to the Head and Neck. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kersey RD. Acute subdural hematoma after a reported mild concussion: a case report. J Athl Train. 1998;33:264–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruno LA, Gennarelli TA, Torg JS. Management guidelines for head injuries in athletics. Clin Sports Med. 1987;6:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guidelines for the Management of Concussion in Sports. Denver, CO: Colorado Medical Society; 1990. Report of the Sports Medicine Committee. revised 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantu RC. Return to play guidelines after head injury. Clin Sports Med. 1998;17:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLatchie G, Jennett B. Head injury in sport. BMJ. 1994;308:1624–1627. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6944.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins M, Lovell M, Mckeag D. Current issues in managing sports-related concussion. JAMA. 1999;24:2283–2285. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]