Abstract

Bullous Pemphigoid Antigen 1 (BPAG1) is a member of the plakin family of proteins. The plakins are multi-domain proteins that have been shown to interact with microtubules, actin filaments and intermediate filaments, as well as proteins found in cellular junctions. These interactions are mediated through different domains on the plakins. The interactions between plakins and components of specialized cell junctions such as desmosomes and hemidesmosomes are mediated through the so-called plakin domain, which is a common feature of the plakins. In this study, we report the crystal structure of a stable fragment from BPAG1, residues 226-448, defined by limited proteolysis of the whole plakin domain. The structure, determined by single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) phasing from a selenomethionine-substituted crystal at 3.0 Å resolution, reveals a tandem pair of triple helical bundles closely related to spectrin repeats. Based on this structure and analysis of sequence conservation, we propose that the architecture of plakin domains is defined by two pairs of spectrin repeats interrupted by a putative Src-Homology 3 (SH3) domain.

Introduction

BPAG1 belongs to the plakin family of proteins that crosslinks the cytoskeleton to each other and connects it to cell junctions1. Plakins constitute a family of large-size proteins expressed in a wide variety of tissues and includes plectin, desmoplakin, MACF1, envoplakin and periplakin in mammals. There are also invertebrate homologs that have been well characterized such as VAB10 and Shortstop in C. elegans and D. melanogaster respectively. Understanding the function of plakins is important because they are associated with several skin and muscle disorders in humans such as bullous pemphigoid, paraneoplastic pemphigus, striate palmoplantar keratoderma and epidermolysis bullosa simplex with muscular dystrophy2. Autoantibodies against one or more plakins are frequently found in the affected individuals, but their role in the pathogenicity of the disorder is not completely understood. Deletions of BPAG1 in mice caused multiple defects, including skin fragility and muscle defects, but the predominant phenotype was sensory neuron degeneration resulting in severe loss of coordination. This phenotype is identical to a naturally occurring mouse mutant called dystonia musculorum, which was subsequently shown to be due to mutations at the BPAG1 locus.

BPAG1 is alternatively spliced leading to three major isoforms, namely BPAG1e, BPAG1a and BPAG1b3. BPAG1e has little in common with BPAG1a and BPAG1b except for a globular domain called the plakin domain that is thought to be an important platform for interactions with proteins in the cell membrane. BPAG1e was first identified as an autoantigen in patients with bullous pemphigoid, a skin blistering disease. BPAG1e connects the keratin intermediate filaments to specialized cell-matrix junctions found in the epithelial tissues called hemidesomosomes. The domain architecture of BPAG1e is tripartite in nature and consists of globular head and tail domains flanking a central coiled coil region. The tail domain of BPAG1e interacts with the intermediate filaments and consists of a series of plakin (or plectin) repeats that folds into multiple plakin repeat domains (PRD). Crystal structures have been determined for the PRDs of desmoplakin, a related epithelial plakin4. The central coiled coil region is thought to enable dimerization of BPAG1e. The globular head domain of BPAG1e encompasses the plakin domain that interacts with proteins associated with hemidesmosomes. BPAG1a and BPAG1b have a common N-terminus that contains a calponin-homology type actin-binding domain (ABD) in front of the plakin domain. These two proteins are missing the central coiled-coil rod domain and the C-terminal PRDs. Instead BPAG1b has a unique PRD region and both proteins have a series of spectrin repeats, followed by a calmodulin-like EF hand and a microtubule-binding domain.

The plakin domain is a common feature of the plakins and serves as an important platform for protein-protein interactions. The binding partners for the plakin domain have been extensively studied in epithelial plakins. For example, the plakin domain of desmoplakin interacts with proteins associated with desmosomes (epithelial cell-cell junctions), such as plakoglobin (γ-catenin), plakophilin-1 and -2, and desmosomal cadherins 5. The plakin domains of plectin and BPAG1 have been shown to interact with proteins associated with hemidesmosomes (epithelial cell-matrix junctions), such as β4 integrin and BPAG26. From secondary structure predictions, the plakin domain of desmoplakin has been suggested to be globular in nature and composed of a series of subdomains, which in turn were predicted to form alpha-helical bundles7. This feature has been suggested to be common among the plakin domains of the entire family of proteins8. Electron microscopic observations and circular dichroism studies of purified fractions of either full-length proteins or fragments of BPAG1e and plectin have confirmed the predicted globular nature of the plakin domain and its predominantly alpha-helical content9; 10. However, there have been no published studies describing the structure of the plakin domain at an atomic scale of resolution.

In this study, we report the crystal structure for a protease resistant fragment of the plakin domain of BPAG1. The overall fold of this structure consists of a triple helical bundle characteristic of spectrin repeats. The fragment consists of two repeats connected by an α-helical linker region. Based on these results, the conservation of key residues important for the folding and stability of spectrin repeats, as well as domain prediction algorithms, we propose that the plakin domains of BPAG1, as well as other plakins include two pairs of spectrin repeats interrupted by a putative SH3 domain. As a result, we suggest that the plakins are members of the spectrin superfamily of proteins that have diverged to attain specific cytolinker functions.

Results

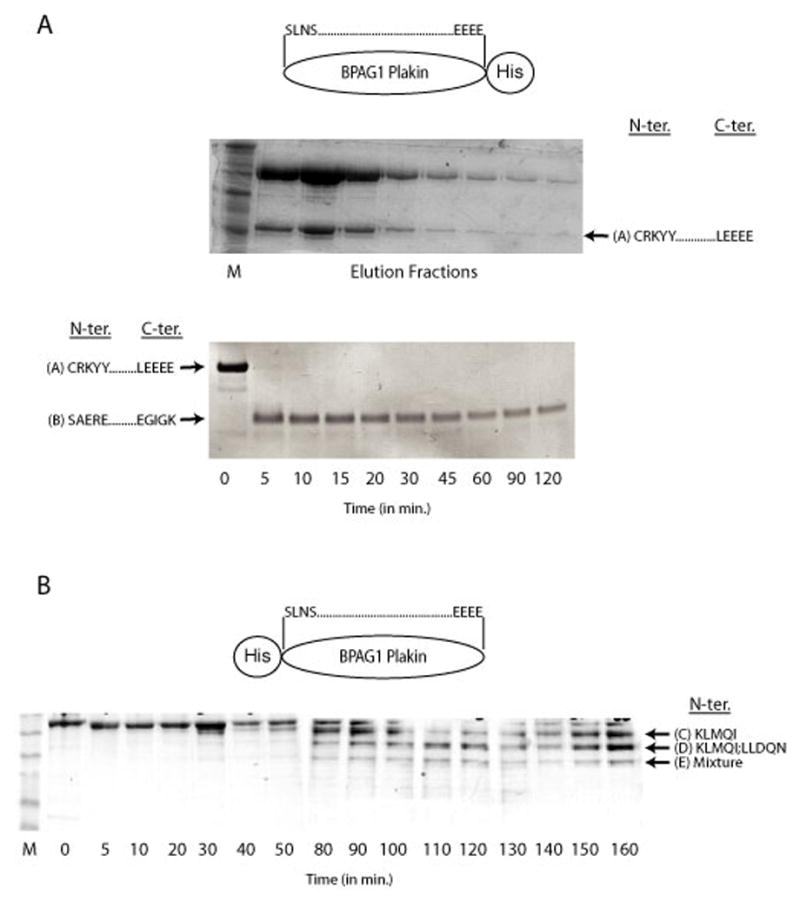

In this study, we solved the crystal structure of an amino-terminal fragment (NT-BP-PKN) of the plakin domain of mouse BPAG1. In order to identify regions that are conducive to form crystals, we sought to identify protease-stable fragments within the plakin domain of BPAG1. Towards this end, constructs encoding the plakin domain of BPAG1 (residues 163–1077 of BPAG1e; Accession No. NP_034211) containing a His-tag at either the N-terminus (N-His BP-PKN) or C-terminus (C-His BP-PKN) were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified. A stable fragment, referred to as A, co-eluted with C-His BP-PKN during the final steps of the purification (Fig. 1A, top). N-terminal sequencing showed that fragment A started with the sequence CRKYY, indicating that fragment A corresponded to the C-terminal half of the plakin domain (Fig. 1C; Table 1). Attempts to produce crystals of fragment A were unsuccessful and it was therefore subjected to further limited proteolysis. Fragment A yielded a smaller fragment, referred to as B, within 5 minutes of digestion with trypsin (Fig. 1A; bottom). This fragment remained resistant to further proteolysis for up to 2 hours. The N-terminus of fragment B was determined by microsequencing and the C-terminus was deduced from its molecular weight (Table 1; Fig. 1C). Fragment B produced micro-crystals, however attempts to improve the size of the crystals were unsuccessful. We therefore decided to identify stable fragments of N-His BP-PKN (Fig. 1B). Limited proteolysis of N-His BP-PKN with proteinase K yielded 3 bands on SDS-PAGE termed C, D and E. (Fig. 1B). N-terminal sequencing showed that C was a single peptide starting with the sequence KLMQI, D contained two peptides (one starting with KMLQI and the other with LLDQN), whereas E consisted of a mixture of peptides. We designed three constructs starting with the sequence KLMQI and ending at different points based on the predicted molecular weight of the proteolytic fragments (C and D) and a third one that went to the end of the plakin domain (see Table 1 and Fig. 1C). Only one of these constructs, termed NT-BP-PKN (amino acids 226–448 of BPAG1e; Accession No. NP_034211) produced a peptide that resulted in suitable crystals, which enabled us to solve its structure (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. (A) Purification of fragments of the C-terminal His-tagged Plakin Domain of BPAG1.

SDS-PAGE of the final step of purification of the C-terminal tagged plakin domain of BPAG1 also yields a proteolytic fragment referred to as A (top gel). Limited proteolysis of fragment A by trypsin produced another fragment, referred to as B (bottom gel). The boundaries of the fragments based on N-terminal sequencing results and mass spectrometry are also shown. (B) Limited Proteolysis of the N-terminal His-tagged Plakin Domain of BPAG1. SDS-PAGE of a time course of a limited Proteinase K digest of the plakin domain of BPAG1with an N-terminal His-tag is shown. The first five N-terminal residues of the various fragments (C and D) are also shown. D contained 2 distinct peptides, whereas E consisted of a mixture of peptides whose identities could not be assigned with certainty. (C) Primary Sequence of the Plakin Domain of BPAG1. The N- and C-terminal amino acids identified in (A) and (B) are indicated in bold. The fragment that produced crystals is underlined. All the fragments used for crystallization experiments are enclosed in brackets and also summarized in Table 1. The first pair of identified spectrin repeats (Repeat 1 and 2), the predicted repeats (Repeat 3 and 4) and the putative SH3 domain are boxed. The alpha-helical regions designated as Z,Y,X,W and V based on the nomenclature of the plakin domain of desmoplakin by Green and colleagues7; 44 are also illustrated (arrows).

Table 1.

Summary of the Fragments Used for Crystallization Experiments. The first 5 residues at the N- and C- terminus of each fragment (see Fig.1A,B) and the result of crystallization screens is shown. Alphabets and numbers in brackets correspond to the identity of the fragments with reference to the primary sequence of the plakin domain of BPAG1 shown in Fig.1C.

| Fragment | Crystals | |

|---|---|---|

| N-terminus | C-terminus | |

| CRKYY (A) | LEEEE (A) | - |

| SAERE (B) | EGIGK (B) | Micro |

| KLMQI (C) | QHIQE (1) | + |

| KLMQI (C) | NKEAV (2) | - |

| KLMQI (C) | LEEEE (3) | - |

The structure of NT-BP-PKN was solved by SAD phasing from a selenomethionine-substituted protein crystal and was refined to a final Rwork of 0.226 and Rfree of 0.266 at 3.0 Å resolution (Table 2). There is one molecule in the asymmetric unit and the final molecule includes 198 residues, 10 water molecules, and 2 sulphate ions. The model has good stereochemistry and most residues occupy allowed regions in the Ramachandran plot. Some regions of the model were built as poly-alanine (residues 141-145 and 161-174), because the side-chains could not be assigned with certainty. There are also regions at both ends (residues 1–4 and 146–160) of the molecule that were not found in the electron density map.

Table 2.

Statistics from Crystallographic Analysis

| Diffraction Data | Se-Met | Native |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | I4132 | I4132 |

| Unit-cell parameters | a=b=c=195.8 Å

α=β=γ=90º |

a=b=c=195.8 Å

α=β=γ=90º |

| Molecules per asymmetric unit | 1 | 1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9791 | 0.9791 |

| Resolution limit (Å) | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Unique Reflections | 24,211 | 13,069 |

| Redundancy | 11.5 | 4.4 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.6 (100) | 98.5 (98.2) |

| Average I/σ (I) | 12.8 (6.7) | 9.9 (3.4) |

| Rmerge (%) | 21.7 (48.9) | 11.9 (35.5) |

| Refinement | ||

| Rwork (%) | 22.6 | |

| Rfree (%) | 26.6 | |

| Rmsd Bonds(Å) | 0.018 | |

| Rmsd Angles(º) | 1.890 | |

| Overall B factor | 41 | |

| No. of residues | 198 | |

| No. of waters | 10 | |

| No. of sulphates | 2 | |

| Ramachandran Plot Regions | ||

| Most favored (%) | 94.2 | |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 4.8 | |

| Generously allowed (%) | 0.5 | |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.5 | |

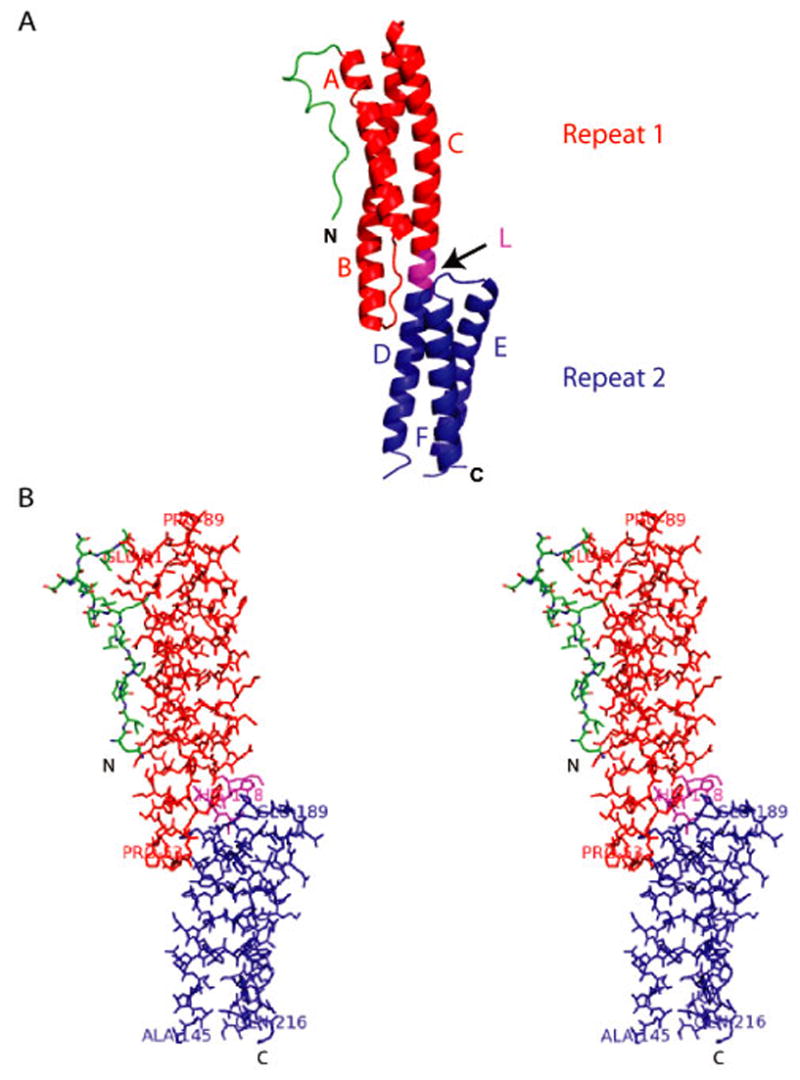

The initial 16 residues at the N-terminus adopt a long loop-like structure followed by a pair of triple helical bundles connected by an α-helical linker region (Fig. 2A,B). The helices are slightly curved and interact with each other to form a characteristic left-handed twist creating a tightly packed core region. This overall fold closely resembles the structure of a spectrin repeat, a hallmark of spectrin superfamily proteins11. The tandem pair of triple helical bundles observed in the structure is therefore designated as spectrin repeat 1 and spectrin repeat 2. The N-terminal repeat (Spectrin Repeat 1) consist of helices A, B and C linked by the AB and the BC loops. The C-terminal repeat (Spectrin Repeat 2) consist of helices D, E and F linked by the DE and the EF loops. Repeat 2 is disordered at one end and as a result, the C-terminus of helix F, the DE loop and parts of helix D and E in proximity to the loop are missing. Helices C and D constitute a single long helix, since the linker connecting the two repeats is itself α-helical in structure. Overall, the molecule has an elongated shape and the dimensions of one complete repeat (Repeat 1) approximate a length of 55 Å and a width of 17 Å.

Figure 2. Structure of the Spectrin Repeats Identified within the Plakin Domain of BPAG1. (A).

A cartoon representation of the structure showing a loop-like region (in green) at the extreme N-terminus followed by a pair of spectrin repeats (Repeat 1 in red and Repeat 2 in blue) in tandem connected by a linker region (L in magenta) that is also helical in nature. The structure consists of helices A, B and C (Repeat 1) and helices D, E and F (Repeat 2). (B) Stereo diagram showing all atoms of the structure shown in (A).

The crystal structures of repeats 15, 16 and 17 of chicken brain α-spectrin, repeats 8 and 9 of human erythroid spectrin and the central spectrin-like repeats of the rod domain of α-actinin12; 13; 14 have been described. All these structures consist of triple helical bundles connected by an extended helical linker region similar to the overall fold of the structure reported here (Fig. 3A). Superposition of spectrin repeat 1 of BPAG1 with repeat 16 of chicken brain α-spectrin shows that the backbones are very similar (rmsd is 1.45 Å for 91 alpha carbon atoms), except in the loops connecting the helices (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, sequence comparison of the spectrin repeats found in BPAG1 with the repeats found in spectrin shows very low sequence identity (less than 30%), although some of the residues important for the stability of the repeats are conserved (Fig. 3A). One of the distinguishing characteristics of spectrin repeats is an extended α-helical linker region connecting two repeats. The margins of the linker regions are not obvious from the structure, however, they can be recognized by a break in the heptad periodicity of helix 3 of Repeat 1 and the beginning of the periodicity of the helix 1 of Repeat 2. This dissociation of heptad periodicity in the linker region places helices A-B and helices E-F on opposite sides of the CD helix, thereby changing the relative orientation of the repeats.

Figure 3. Comparison of Spectrin Repeats of BPAG1 and Spectrin. (A).

Amino-acid sequence alignment of spectrin repeats (Repeat 1 and Repeat 2) identified within the plakin domain of BPAG1 with the representative spectrin repeats of known structure. The residues involved in the stacking interactions are shown (arrows). Conserved residues are highlighted in red and boxed in blue. SR-Spectrin repeat; HuEry-Human Erythroid; ChBr-Chicken Brain; AlphaAct-Alpha Actinin. (B) Stereoview of a superposition of spectrin repeat 1 of BPAG1 (red) with repeat 16 of chicken brain α-spectrin (blue). Rmsd=1.49Å for 91 alpha carbon atoms. (C) Inter-helical stacking interactions that are highly conserved in spectrin repeats involving a residue in each of the three helices constituting a repeat is illustrated.

Spectrin repeats have highly conserved tryptophan residues in the first and third helices, which have been shown to contribute to the conformational stability of the helical bundles15; 16. There is a highly conserved tryptophan (W35) in the first helix and a tyrosine (Y105) replacing the conserved tryptophan in the third helix of Repeat 1 of BPAG1. These two residues are involved in stacking interactions along with a phenylalanine (F72) residue present in the second helix (Fig. 3C). There are equivalent interactions in Repeat 16 of chicken brain α-spectrin involving W21, H58 and W94 (Fig. 3C). It is also important to point out that the change in the phasing of the heptad pattern due to missing residues in Repeats 16 and 17 of chicken brain α-spectrin (referred to as a ‘stammer’), is also present in the spectrin repeats of BPAG1, illustrating a close similarity in the basic architecture of the repeats 17.

The main difference between the structure of NT-BP-PKN and the spectrin repeats of the spectrin family is in the initial segment of ~20 residues. This region is non-helical in nature, even though secondary structure predictions suggest a helical region. There are certain interactions between this region and helix 1 of Repeat 1, such as the ionic interaction between R6 and D31 and the hydrophobic interaction between P8 and W35 that are important for the observed conformation (Fig. 2B).

To determine whether the spectrin repeats identified within the plakin domain of BPAG1 might be a general feature of the entire plakin family, we performed a multiple sequence alignment of NT-BP-PKN with equivalent regions from other plakins (Fig. 4). NT-BP-PKN is highly conserved (> 90% identity) between mouse and human. NT-BP-PKN also shows 50% identity with mouse MACF except for the first 5 residues that are dissimilar. However, the initial 16 residues constituting the loop-like structure (green in Fig. 2) is highly divergent between BPAG1 and all the other plakins, potentially contributing to specificity of biological function. The spectrin repeats of BPAG1 are 50% identical to a similar region in plectin and around 35% identical to desmoplakin, periplakin, and the invertebrate plakins, shortstop and VAB10. The conservation with envoplakin, one of the plakin found in the corneal envelope, is the lowest (around 25%). Although the overall sequence identities of the spectrin repeats are not always very high, certain hydrophobic residues are highly conserved among all the plakins, including the tryptophan in helix 1 that forms stacking interactions with residues in helix 2 and 3. The initial segment of NT-BP-PKN that is non-helical and adopts a loop like structure, comprising around 20 residues, appears to be unique to the plakin family. Based on sequence similarities with the spectrin repeat of BPAG1 and conservation of predominantly hydrophobic residues presumably important for the stability and folding of the repeats, it is likely that the plakin domains of all the plakin family of proteins consist of at least two spectrin repeats in the N-terminus of the domain.

Figure 4. BPAG1 and Other Plakins.

Amino-acid sequence alignment of the fragment of BPAG1 (NT-BP-PKN) that produced crystals with other plakins is shown. The N-terminal region that forms a loop like structure is not conserved except with human BPAG1 where the overall conservation is high (>90%). The hydrophobic residues that form stacking interactions to stabilize the repeat are highly conserved in most plakins (arrows). Conserved residues are highlighted in red and boxed in blue. h-Homo sapiens; m-Mus musculus.

The long isoforms of certain plakins, such as BPAG1a, BPAG1b, MACF1a, MACF1b, Shot I, Shot II and VAB-10 B are predicted to contain long stretches of spectrin repeats and were therefore referred to as ‘spectraplakins’22. The role of these numerous spectrin repeats in the spectraplakins is not completely understood. In the original report describing the cloning and characterization of the major isoforms of BPAG1, 23 repeats were predicted outside the plakin domain3. We have identified 32 predicted spectrin repeats in the BPAG1a/b isoforms, including the 4 repeats found within the plakin domain. The deduction of the other five repeats not previously identified reflects improvements in prediction algorithms. Amino acid sequence comparisons of the spectrin repeats in the plakin domain of BPAG1 with the C-terminal spectrin repeats of the BPAG1a/b isoforms do not show a high degree of conservation (less than 30%). However, there are 19 residues that are highly conserved and all except one are hydrophobic suggesting that they might be involved in the core interactions important for the stability of the repeat (Fig. 5). The highly conserved tryptophan in helix 1, shown experimentally to be important for the stability of the repeat, is present in most, but not all repeats15; 16. There is also a high degree of variability in the loops connecting the three helices of the different repeats. There are gaps in the alignment suggesting that the helices differ in their lengths. The putative repeats 3, 7 and 32 are unusual in that they contain additional residues in the predicted loop regions connecting helix B and C.

Figure 5. Comparison of Spectrin Repeats Within and Outside of the Plakin Domain of BPAG1.

Amino-acid sequence alignment of the two spectrin repeats (R1 and R2) identified within the plakin domain of BPAG1 and the other spectrin repeats predicted outside the plakin domain of larger isoforms such as BPAG1a and BPAG1b. Conserved residues are highlighted in red and boxed in blue. Also included are additional repeats (R3 and R4) predicted within the plakin domain. Overall, there are 4 spectrin repeats in BPAG1e and 32 spectrin repeats in BPAG1a and BPAG1b. SR-spectrin repeat. The number following the prefix, SR, indicates the position of the spectrin repeat in sequential order.

In addition to the first pair of spectrin repeats identified by the crystal structure, domain prediction algorithms suggest that the plakin domains of BPAG1, as well as the other plakins, contain a second pair of spectrin repeats, as well as a central SH3 domain with intervening alpha helical regions18; 19; 20. Using 3D-JIGSAW, an automated system that builds three-dimensional models of proteins based on homologues of known structure, we built a model of the SH3 domain of BPAG1 (left; Fig. 6A)21. Superposition of the model of the SH3 domains of BPAG1 and the crystal structure of the SH3 domain of alpha-spectrin (right; Fig. 6A) indicates that the major difference lies in the RT-loop due to the presence of three extra residues in alpha-spectrin. The degree of conservation (identical amino acids) between the SH3 domain of BPAG1 and alpha-spectrin is around 25% and between 15–25 % with representative proteins containing the SH3 domain (Fig. 6B). The binding pockets of SH3 domains consists of highly conserved aromatic and hydrophobic residues on the surface that could interact with proline rich sequences bearing the “PXXP” motif. Based on the model of the SH3 domain of BPAG1, two of the exposed aromatic residues in this binding pocket have been replaced by cysteines in most plakins (8 and 52 in Fig. 6B). The biological significance of this substitution is not clear. The presence of a SH3 domain in the midst of spectrin repeats also occurs in other members of the spectrin family of proteins. Based on predictions, the SH3 domain of alpha-spectrin is confined to repeat 9, situated between helix 2 and helix 3 of the repeat. In contrast, domain prediction algorithms18 do not show spectrin repeats in the region encompassing the SH3 domain of the plakin domain of BPAG1, suggesting that it is not placed in the midst of an interrupted repeat. Structural studies of this region should determine whether this prediction is correct.

Figure 6. Putative SH3 domain of BPAG1. (A).

Model of the SH3 domain of BPAG1 (in red; on top left) is shown. Superposition (on top right) of the crystal structure of SH3 domain of alpha-spectrin (in green) with the model of the SH3 domain of BPAG1 shows that the RT loop is larger in alpha-spectrin due to the presence of three extra residues. (B) Structure based amino-acid sequence alignment of the putative SH3 domain of BPAG1 with equivalent regions from other plakins, the SH3 domain of alpha-spectrin and representative Src family of proteins. The five anti-parallel beta-strands (β-1 to β-5) forming the SH3 domain of alpha-spectrin are indicated (horizontal arrows on top). The five residues important for interactions, based on the structural analysis of the complexes between SH3 domain and proline-rich ligands, are also shown (vertical arrows at the bottom). m-Mus musculus

Since the crystal structure solved in this study revealed the presence of a pair of spectrin repeats and structure prediction algorithms indicated another pair of repeats within the plakin domain of BPAG1, we wanted to understand the evolutionary relationship of the plakin family of proteins to the spectrin superfamily. A phylogenetic tree constructed on the basis of the sequence of the very first pair of repeats showed interesting features (Fig. 7C). Not surprisingly, the plakins are more closely related to each other than to the spectrins. Within the plakin family, proteins that have similar functions are clustered together. BPAG1 is very closely related to its homologue, MACF1, with which it shares the highest percentage of sequence identity (Fig. 4). BPAG1 is also closer to plectin, both of which are components of hemidesmosomes, than to desmoplakin that is found in desmosomes. Epiplakin and periplakin, epithelial plakins that are both found in the cornified envelope, are related to each other and are further divergent from BPAG1. Invertebrate plakins are the most divergent from BPAG1.

Figure 7. (A) Nomenclature of the Plakin Domain.

The spectrin repeats identified within the plakin domain of BPAG1 are shown in the context of the old nomenclature of the plakin domain of desmoplakin 7, which were predicted to consist of a series of alpha helical bundles termed - Z, Y, X, W and V. The pair of repeats includes the entire Z domain and most of the Y domain. Also shown is the proposed domain architecture of the entire plakin domain of BPAG1, based on the crystal structure reported in this study and domain prediction algorithms.

(B) Domain Architecture of Plakins and Spectrins. A schematic of the major isoforms of BPAG1 and the alpha- and beta- subunits of erythroid spectrin is shown to highlight the similarities between the plakin and spectrin family of proteins. PRD-plakin repeat domains; ABD-actin binding domain; MTBD-microtubule binding domain. Whereas the amino-terminal ends are similar consisting of either the ABD or spectrin repeats in both families, the carboxyl-terminal ends are divergent. Plakins consist of domains that can interact directly with either microtubules or intermediate filaments extending their cytolinker functions to all the three major cytoskeletal networks in the cell.

(C) Evolutionary Relationship Between Plakins and Spectrins. The phylogenetic tree of plakins and spectrins based on the percent identity of the first pair of spectrin repeats is shown. Members of the plakin family included are BPAG1 and its close homologue MACF, plakins found in desmosomes and hemidesmosomes, plectin and desmoplakin and those present in the cornified envelope of skin, periplakin and envoplakin. Shortstop and VAB10 are plakin family orthologs found in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans, respectively. Members of the spectrin family included are alpha-actinin, alpha- and beta- chains of erythroid spectrin, dystrophin, utrophin and nesprin. d-Drosophila melanogaster; h-Homo sapiens; m-Mus musculus

Discussion

We have reported the crystal structure of a part of the plakin domain of BPAG1 at 3.0 Å resolution. The boundaries of this fragment (NT-BP-PKN) were designed on the basis of limited proteolysis experiments. The structure consists of a pair of triple helical bundles composed of slightly curved anti-parallel α-helices separated by two loops that wrap around each other into a left-handed supercoil and connected by a helical linker region. This overall fold of the helices resembles a pair of spectrin repeats that is an important feature found in the spectrin family of proteins.

The epithelial plakins are thought to adopt characteristic tripartite dumbbell shaped structures with globular head and tail domains flanking a central coiled coil region7. Desmoplakin is a classic epithelial plakin and its overall domain architecture resembles other epithelial plakins, such as BPAG1e and plectin (Fig. 7A). The crystal structure of the tail domain (PRD B and C) of desmoplakin has been determined and shows a globular fold 4. The head domain of desmoplakin encompassing the plakin domain has been shown to be important for localizing to the junctions by interacting with the armadillo proteins and desmosomal cadherins. Sequence-based structure predictions of desmoplakin by Green and colleagues suggested that the plakin domain consists of a series of α-helical bundles – termed Z,Y,X,W and V, which folds into the putative N-terminal globular domain5; 23. The spectrin repeat domains, which are essentially triple helical bundles, identified within the plakin domain of BPAG1 in this study, are out of register with these predicted helical bundles. Based on sequence alignment, the two spectrin repeats includes the entire Z domain and most of the Y domain (Figs. 1C and 7A). Domain prediction algorithms predicted a second pair of spectrin repeats and a putative SH3 domain within the plakin domain18; 19; 20. Specific functions and ligands of the SH3 domain of spectrin have been identified24; 25; 26; 27; 28; 29. It is therefore likely that interactions associated with the plakin domain of BPAG1 (and other plakins) either to known and/or yet to be identified ligands are mediated in part by these putative SH3 domains. Interestingly, the minimal region of Erbin that was shown to be sufficient to interact with the plakin domain of BPAG1 contains proline rich signature sequences characteristic of SH3 domain binding ligands30. Interactions of the N-terminus of BPAG1 with the cytoplasmic region of hemidesmosomal proteins, BPAG2 and β4 integrin have been studied extensively6. Interaction with β4 integrin requires the extreme N-terminus that is unique to BPAG1e, however additional regions within the plakin domain are also involved. The minimal region of BPAG1 required to interact with BPAG2 include the region that contains the spectrin repeats in the plakin domain. However, the fragment used for crystallization in this study was not sufficient to interact with either BPAG2 or β4 integrin (data not shown). It is possible that the interaction of BPAG2 with these repeats are weak and/or the repeats have only indirect effects on binding. In utrophin, the spectrin repeats regulate the binding of the CH domains to actin by affecting the affinity and stoichiometry of interaction31.

The spectrin superfamily of proteins are actin cross-linking proteins that contain a calponin-type ABD at their N-termini followed by multiple spectrin repeats that could specify characteristic actin cross linking distance. There are 4 repeats in α-actinin, 20 in α-spectrin, 17 in β-spectrin, 24 in dystrophin and 20 in utrophin. Whether the presence of the large number of spectrin repeats at one end of the plakin isoforms designated as ‘spectraplakins’ imparts flexibility relevant to their biological functions remains an intriguing possibility22. The presence of spectrin repeats within the plakin domain, common to all plakins (except epiplakin), suggests that the domain organization of the entire plakin family is similar to the spectrin superfamily (Fig. 7B). The N-terminal halves of both spectrins and plakins generally consist in part of combinations of ABDs, spectrin repeats and SH3 domains. The plakins diverge from other spectrins in their C-terminal ends conferring on the plakins the ability to interact directly with either intermediate filaments or microtubules. The results presented in this report suggest that plakins are members of the spectrin superfamily of proteins that have evolved new functions over time such as their ability to organize the intricate network of intermediate filaments and microtubules within the cell, through the acquisition of additional domains to allow for additional interactions with these other cytoskeletal elements.

Materials and Methods

The plakin domain of BPAG1 (BP-PKN; encoding residues 163–1077 of BPAG1e; Accession No. NP_034211) was initially cloned into pET-16d and pET-21b (Novagen) to produce a Histidine tagged fusion protein at the N-terminus (N-His BP-PKN) and C-terminus (C-His BP-PKN) respectively, using Nde1 and Xho1 restriction sites. Subsequently, the construct was overexpressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) and purified by affinity chromatography on a HisBind Resin (Novagen). A stable fragment co-eluted with the full-length C-His BP-PKN during the final steps of purification. The protein samples were subsequently run on SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (BioRad) for N-terminal sequencing.

Purified aliquots (1mg/ml) of N-His BP-PKN was subject to limited proteolysis by Proteinase K (10mg/ml) at 37 º C under different enzyme substrate concentrations (1:100 – 1:1000000). The reactions were stopped by heat inactivation every 10 minutes for 120 minutes and the reaction mixtures were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by transfer to a PVDF membrane (BioRad) for N-terminal sequencing of the resulting fragments. The C-termini were deduced empirically based on the approximate molecular weight of the fragments. One of the fragments referred to as NT-BP-PKN (encoding residues 226–448 of BPAG1e; Accession No. NP_034211) was cloned into a pET-SUMO vector (Invitrogen), overexpressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) and induced with 1 mM isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside at 18º C for 12–18 hours. Expression of selenomethionine substituted NT-BP-PKN was achieved using M9 medium supplemented with selenomethionine (Sigma)32. The protein was initially purified by affinity chromatography using Ni Sepharose ™ High Performance (Amersham Biosciences) resin and the tag was removed by incubating the elution fraction with Ulp protease at 4 ºC for 3-4 hours. The protein was further purified by ion-exchange and gel filtration chromatography using a Q Sepharose and S-75 column (Amersham Biosciences) respectively. Purified protein was concentrated to 40 mg/ml in 20mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0) using Amicon centrifugation filters (Bio Rad) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Crystals were obtained by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method using multiple commercially available screens (Hampton Research). The crystallization conditions were optimized to improve the size and the largest crystals were obtained in 1.6 M ammonium sulphate, 50 mM 3-(cyclohexylamino)-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonic Acid (pH 9.2) and 5 mM dithiothreitol at 20º C. Crystals grew to approximately 0.08 x 0.08 x 0.08 mm3 overnight. All the data were collected at National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) beamline X29A at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) with cryocooled crystals in a mother liquor solution supplemented with 30% glycerol. The data was integrated and scaled with the program XDS33 and CCP4 program suites34; 35. The crystals belong to cubic space group I4132, with a=b=c=195.8Å, with one molecule per asymmetric unit and 57 % solvent content.

The structure was determined by a SAD experiment using data from a selenomethionine substituted protein crystal collected to 3.0 Šresolution. Of the six possible selenium sites, four sites were found with the program SHELXD36. The phases were further improved using the density modification program PIRATE37. Since most of the structure was helical in nature, the resulting electron density map was sufficient to build more than 90% of the model automatically using BUCCANEER38. Non-helical regions were built manually using the program COOT39. The model was refined using native data to 3.0 ź resolution with the program CNS40 and REFMAC41. One overall anisotropic temperature factor was refined together with 4 TLS groups41. Ordered water molecules were identified in fo-fc difference map using COOT and checked manually for proximity to hydrogen bonding partners. Two unexplained electron density peaks were modeled as sulphate ions based on the number of electrons, proximity to positively charged groups and the conditions used for crystallization. Predictions of secondary structure were carried out using Predict Protein 42 and multiple sources were used for predictions of domain architecture of the plakin domain of BPAG1 18; 19; 20. Model of the SH3 domain of BPAG1 was built using 3D-JIGSAW21 and superposition with the SH3 domain of spectrin (PDB ID:1SHG) was done using the program PyMol. All the figures were produced using PyMOL43 and CCP4mg34.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Jamie Schwartz for her assistance in preparing some of the constructs and members of the Shapiro lab for their expertise and suggestions. We also thank the staff of NSLS at the X-29 beam line, Brookhaven National Laboratory for their assistance. This work was supported by grants NS47711 and GM62270 from the National Institutes of Health. LS is partly supported by a grant from the RPB foundation.

Footnotes

Protein Data Bank accession number

The coordinates and structure factors for the structure of BP-NT-PKN described in this study have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the accession number 2IAK.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jefferson JJ, Leung CL, Liem RK. Plakins: goliaths that link cell junctions and the cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:542–53. doi: 10.1038/nrm1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung CL, Green KJ, Liem RK. Plakins: a family of versatile cytolinker proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung CL, Zheng M, Prater SM, Liem RK. The BPAG1 locus: Alternative splicing produces multiple isoforms with distinct cytoskeletal linker domains, including predominant isoforms in neurons and muscles. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:691–7. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200012098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi HJ, Park-Snyder S, Pascoe LT, Green KJ, Weis WI. Structures of two intermediate filament-binding fragments of desmoplakin reveal a unique repeat motif structure. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:612–20. doi: 10.1038/nsb818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Getsios S, Huen AC, Green KJ. Working out the strength and flexibility of desmosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:271–81. doi: 10.1038/nrm1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koster J, Geerts D, Favre B, Borradori L, Sonnenberg A. Analysis of the interactions between BP180, BP230, plectin and the integrin alpha6beta4 important for hemidesmosome assembly. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:387–99. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virata ML, Wagner RM, Parry DA, Green KJ. Molecular structure of the human desmoplakin I and II amino terminus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:544–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green KJ, Bohringer M, Gocken T, Jones JC. Intermediate filament associated proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;70:143–202. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foisner R, Wiche G. Structure and hydrodynamic properties of plectin molecules. J Mol Biol. 1987;198:515–31. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang HY, Chaffotte AF, Thacher SM. Structural analysis of the predicted coiled-coil rod domain of the cytoplasmic bullous pemphigoid antigen (BPAG1). Empirical localization of the N-terminal globular domain-rod boundary. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9716–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broderick MJ, Winder SJ. Spectrin, alpha-actinin, and dystrophin. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;70:203–46. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusunoki H, MacDonald RI, Mondragon A. Structural insights into the stability and flexibility of unusual erythroid spectrin repeats. Structure. 2004;12:645–56. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ylanne J, Scheffzek K, Young P, Saraste M. Crystal Structure of the alpha-Actinin Rod: Four Spectrin Repeats Forming a Thight Dimer. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2001;6:234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grum VL, Li D, MacDonald RI, Mondragon A. Structures of two repeats of spectrin suggest models of flexibility. Cell. 1999;98:523–35. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81980-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pantazatos DP, MacDonald RI. Site-directed mutagenesis of either the highly conserved Trp-22 or the moderately conserved Trp-95 to a large, hydrophobic residue reduces the thermodynamic stability of a spectrin repeating unit. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21052–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacDonald RI, Musacchio A, Holmgren RA, Saraste M. Invariant tryptophan at a shielded site promotes folding of the conformational unit of spectrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1299–303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown JH, Cohen C, Parry DA. Heptad breaks in alpha-helical coiled coils: stutters and stammers. Proteins. 1996;26:134–45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199610)26:2<134::AID-PROT3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Letunic I, Copley RR, Pils B, Pinkert S, Schultz J, Bork P. SMART 5: domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D257–60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finn RD, Mistry J, Schuster-Bockler B, Griffiths-Jones S, Hollich V, Lassmann T, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Durbin R, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer EL, Bateman A. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Cherukuri PF, DeWeese-Scott C, Geer LY, Gwadz M, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Lanczycki CJ, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Shoemaker BA, Simonyan V, Song JS, Thiessen PA, Yamashita RA, Yin JJ, Zhang D, Bryant SH. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for protein classification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D192–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bates PA, Kelley LA, MacCallum RM, Sternberg MJ. Enhancement of protein modeling by human intervention in applying the automatic programs 3D-JIGSAW and 3D-PSSM. Proteins Suppl. 2001;5:39–46. doi: 10.1002/prot.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roper K, Gregory SL, Brown NH. The 'spectraplakins': cytoskeletal giants with characteristics of both spectrin and plakin families. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4215–25. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green KJ, Gaudry CA. Are desmosomes more than tethers for intermediate filaments? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:208–16. doi: 10.1038/35043032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nedrelow JH, Cianci CD, Morrow JS. c-Src binds alpha II spectrin's Src homology 3 (SH3) domain and blocks calpain susceptibility by phosphorylating Tyr1176. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7735–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chow CW, Woodside M, Demaurex N, Yu FH, Plant P, Rotin D, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Proline-rich motifs of the Na+/H+ exchanger 2 isoform. Binding of Src homology domain 3 and role in apical targeting in epithelia. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10481–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rotin D, Bar-Sagi D, O'Brodovich H, Merilainen J, Lehto VP, Canessa CM, Rossier BC, Downey GP. An SH3 binding region in the epithelial Na+ channel (alpha rENaC) mediates its localization at the apical membrane. Embo J. 1994;13:4440–50. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolas G, Fournier CM, Galand C, Malbert-Colas L, Bournier O, Kroviarski Y, Bourgeois M, Camonis JH, Dhermy D, Grandchamp B, Lecomte MC. Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates alpha II spectrin cleavage by calpain. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3527–36. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3527-3536.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziemnicka-Kotula D, Xu J, Gu H, Potempska A, Kim KS, Jenkins EC, Trenkner E, Kotula L. Identification of a candidate human spectrin Src homology 3 domain-binding protein suggests a general mechanism of association of tyrosine kinases with the spectrin-based membrane skeleton. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13681–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bialkowska K, Saido TC, Fox JE. SH3 domain of spectrin participates in the activation of Rac in specialized calpain-induced integrin signaling complexes. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:381–95. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Favre B, Fontao L, Koster J, Shafaatian R, Jaunin F, Saurat JH, Sonnenberg A, Borradori L. The hemidesmosomal protein bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 and the integrin beta 4 subunit bind to ERBIN. Molecular cloning of multiple alternative splice variants of ERBIN and analysis of their tissue expression. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32427–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rybakova IN, Ervasti JM. Identification of spectrin-like repeats required for high affinity utrophinactin interaction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23018–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doublie S. Methods in Enzymology. In: Carter CW, Sweet RM, editors. Macromolecular Crystallography, Part A. Vol. 276. Academic Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabsch W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Cryst. 1993;21:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potterton L, McNicholas S, Krissinel E, Gruber J, Cowtan K, Emsley P, Murshudov GN, Cohen S, Perrakis A, Noble M. Developments in the CCP4 molecular-graphics project. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2288–94. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–3. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1772–9. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cowtan K. General quadratic functions in real and reciprocal space and their application to likelihood phasing. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:1612–21. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900013263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cowtan K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1002–11. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906022116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–21. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winn MD, Murshudov GN, Papiz MZ. Macromolecular TLS refinement in REFMAC at moderate resolutions. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:300–21. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rost B, Liu J. The PredictProtein server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3300–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; San Carlos, CA, USA: 2002. http://www.pymol.org. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green KJ, Virata ML, Elgart GW, Stanley JR, Parry DA. Comparative structural analysis of desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigen and plectin: members of a new gene family involved in organization of intermediate filaments. Int J Biol Macromol. 1992;14:145–53. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(05)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]