Abstract

Recent studies have shown that people with poor early growth have an increased risk of sarcopenia. Sarcopenia is an important risk factor for falls but it is not known whether poor early growth is related to falls. We investigated this in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study where 2148 participants completed a falls history. Grip strength was used as a marker of sarcopenia. Birth weight, weight at one year and conditional infant growth were analysed in relation to falls history. The prevalence of any fall in the last year was 14.3% for men and 22.5% for women. Falls in the last year were inversely related to adult grip strength, height and walking speed in men and women as well as to lower conditional infant growth in men (OR 1.27 [95% CI 1.04, 1.56] per SD decrease in conditional infant growth, p=0.02). This association was attenuated after adjustment for grip strength. Our findings support an association between poor early growth and falls in older men which appears to be mediated partly through sarcopenia. The lack of relationship with birth weight suggests that postnatal rather than prenatal influences on muscle growth and development may be important for risk of falls in later life.

Keywords: Falls accidental, muscle skeletal, muscle development, frail older adults, geriatrics, epidemiology, cohort studies

The high prevalence and incidence of falls in community dwelling older people has been reported for many years(1) and there is growing recognition of the serious consequences for health in terms of disability, morbidity and mortality as well as economic cost(2-5). Over 400 potential risk factors for falling have been identified but a consistent finding is the link with sarcopenia; loss of muscle mass and strength with age(6;7). This has led to the inclusion of targeted exercise programmes in multi-factorial interventions to reduce the risk of falling by maximising muscle function in older people(8-13). However there remain some difficulties in implementing effective secondary prevention programmes and progress with primary prevention both in terms of developing suitable screening tools and effective interventions has been slower(14;15). At present the best predictor of having a fall is having had one previously.

Investigating the risk factors for sarcopenia is one approach to the primary prevention of falls. The most important modifiable influence is level of physical activity but it is of note that muscle loss occurs even in elite athletes who maintain high levels of exercise in later life(16). There have been estimates of moderate heritability(17) with a number of candidate genes proposed(18-20) but there remains considerable unexplained variation in both the muscle mass and strength of men and women in later life. Recent work has shifted attention away from adult influences on muscle and focused on factors operating earlier in the life course(21). A number of epidemiological studies have now shown that men and women who grew less well in early life have lower adult muscle mass and strength independent of adult size(21-26). The underlying mechanism is not known but may reflect persisting altered muscle fibre type, proportion or quality.

It is not known whether poor early growth is related to falls in later life. We have investigated the inter-relationship between early growth, sarcopenia and falls in a group of older men and women participating in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study.

METHODS

Study population

The Hertfordshire Cohort Study has been described in detail previously including comparison with the nationally representative Health Survey for England(27). This demonstrated broad similarities between the two cohorts, for example with regard to socioeconomic, anthropometric, medical and functional characteristics of the participants, although there was some evidence of a ‘healthy subject’ effect. The historical background to the study originates in the period between 1911 and 1948 when midwives recorded information on birth weight and weight at one year on infants born in the English county of Hertfordshire. The records for people born 1911-1930 have been used in a series of studies linking early growth to health in later life. In 1998, a younger cohort was recruited to participate in studies examining the interactions between early life, diet, adult lifestyle and genetic factors as determinants of adult disease. 3822 men and 3284 women born in Hertfordshire between 1931 and 1939 and still living in the county were traced with the aid of the NHS central registry in Southport and confirmed as currently registered with a General Practitioner in Hertfordshire. Fieldwork was conducted over a period of five years phased by region of Hertfordshire (East, North, West). Initial findings from this study were based on participants from East Hertfordshire(21;22); this study includes participants from the whole county.

Permission to contact 3126 (82%) men and 2973 (91%) women was obtained from their General Practitioners as registration with a state General Practitioner is near universal in England. 1684 (54%) men and 1541 (52%) women aged 59-73 years agreed to take part in a home interview where trained nurses collected information on their medical and social history including self-reported walking speed (six categories: unable to walk, very slow, stroll at an easy pace, normal speed, fairly brisk and fast), alcohol intake (units per week), smoking habit (three categories: never, ex and current smoker), and social class (classified using the 1990 OPCS Standard Occupational Classification scheme for occupation and social class where social class was identified on the basis of own current or most recent full-time occupation for men and never-married women, and on the basis of the husband’s occupation for ever-married women). A question about having had any falls in the past year was included in the home interview part way through the study; falls data were therefore only available for 941 men and 1398 women. 866 (92%) of these men and 1282 (92%) of these women subsequently attended a clinic for a number of investigations (median time between home interview and clinic was 5 weeks). Anthropometry included measurement of height and weight(28). Skinfold thickness (SFT) was measured with Harpenden skinfold calipers in triplicate at the triceps, biceps, sub-scapular and supra-iliac sites on the non-dominant side(29). Grip strength was measured three times on each side using a Jamar handgrip dynamometer(30) as a marker of sarcopenia(31). Intra-observer and inter-observer studies were carried out at regular intervals during the fieldwork to ensure comparability of measurements within and between observers. The study had ethical approval from the Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire Local Research Ethics Committee and all subjects gave written informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

The best of the six grip measurements was coded for analyses. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2. The averages of the triplicate skinfold measures at each site were taken and body fat percentage was derived from the four average skinfold measurements according to the method proposed by Durnin and Womersley(32). Fat mass was derived by multiplying body weight by body fat percentage. Non-fat mass was estimated by subtracting fat mass from body weight. Normality of variables was assessed and BMI and fat mass were loge transformed.

Sex-specific standard deviation (SD) scores were calculated for birth weight, weight at one year and conditional infant growth (equivalent to an SD score for weight at one year independent of birth weight)(33). The SD score for conditional infant growth was free of the artefactual effects of regression to the mean and enabled the effects of birth weight and infant weight gain on falls risk to be clearly distinguished.

All analyses were carried out for men and women separately using the Stata statistical software package, release 8.0 (Stata Corporation 2003). The genders were analysed separately because of a priori knowledge that both rate of falls and patterns of early growth differ between men and women although there was no statistical evidence of an interaction between gender and early growth on falls history in this data.

Subject characteristics were summarised for fallers and non-fallers using means and standard deviations, or frequency and percentage distributions. Two-sample t-tests and Chi-squared tests were used to test univariate relationships between each subject characteristic and falls history. Characteristics significantly associated with falls history in univariate analyses were subsequently included in multivariate logistic regression models; results were presented as odds ratios (OR) for falls history with associated 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) and p-values. However odds ratios were likely to overestimate the relative risk in this study because falls were common.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the 2148 study participants are shown in Table 1 according to falls history. The prevalence of having had a fall in the past year was 14.3% in men and 22.5% in women (odds ratio for falls history in women compared with men: 1.74 [95%CI 1.38, 2.19], p<0.001). Men who had fallen in the past year had lower weight at one year and conditional infant growth, lower grip strength, shorter stature and were more likely to report slower walking speeds. Women who had fallen in the past year had lower grip strength, shorter stature, greater body mass index, and were more likely to report slower walking speeds. Birth weight, adult weight, fat-mass and non-fat mass, social class, smoking habit and alcohol consumption were not related to falls history in men or women and were not considered further in analyses. Chronological age was not associated with falls history in men or women but this variable was included in mutually adjusted analyses. Conditional infant growth was more strongly related to falls history in men than weight at one year and was therefore included in mutually adjusted analyses. Conditional infant growth was also included in mutually adjusted models for women owing to a priori interest in its relationship with falls risk in adulthood.

Table 1.

Hertfordshire Cohort Study: subject characteristics according to gender and falls history

| MEN (n=866) | WOMEN (n=1282) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fall in the past year |

Fall in the past year |

|||||

| Mean (SD) | No (n=742) | Yes (n=124) | p-value* | No (n=993) | Yes (n=289) | p-value* |

| Birth weight (lb) | 7.7 (1.2) | 7.7 (1.2) | 0.86 | 7.4 (1.1) | 7.4 (1.2) | 0.97 |

| Weight at one year (lb) | 22.7 (2.3) | 22.2 (2.2) | 0.04 | 21.5 (2.2) | 21.3 (2.3) | 0.15 |

| Conditional infant growth (SD-score) | 0.12 (0.97) | -0.10 (0.97) | 0.02 | 0.09 (0.98) | -0.01 (1.00) | 0.13 |

| Age (yrs) | 66.8 (2.6) | 66.9 (2.6) | 0.72 | 66.8 (2.6) | 66.9 (2.9) | 0.48 |

| Grip strength (kg) | 44.3 (7.6) | 41.8 (8.0) | 0.009 | 26.7 (5.8) | 25.7 (5.8) | 0.01 |

| Height (cm) | 174.4 (6.3) | 173.2 (6.3) | 0.05 | 161.0 (5.8) | 160.2 (6.0) | 0.06 |

| Weight (kg) | 82.8 (12.6) | 82.3 (14.6) | 0.70 | 71.1 (13.3) | 72.5 (13.5) | 0.11 |

| Fat mass (kg)** | 23.2 (1.4) | 22.4 (1.4) | 0.27 | 27.5 (1.3) | 28.4 (1.3) | 0.12 |

| Non-fat mass (kg) | 58.5 (6.9) | 58.7 (8.2) | 0.81 | 42.3 (5.9) | 42.9 (6.0) | 0.13 |

| BMI (kg/m2)** | 27.0 (1.10 | 27.1 (1.2) | 0.73 | 27.0 (1.2) | 27.7 (1.2) | 0.01 |

| Frequency (%) | ||||||

| Walking speed: Very slow | 26 (3.5) | 13 (10.6) | 54 (5.4) | 36 (12.5) | ||

| Stroll at an easy pace | 174 (23.5) | 37 (30.1) | 182 (18.3) | 74 (25.6) | ||

| Normal speed | 300 (40.4) | 35 (28.5) | 0.001 | 467 (47.0) | 110 (38.1) | <0.001 |

| Fairly brisk | 212 (28.6) | 35 (28.5) | 231 (23.3) | 57 (19.7) | ||

| Fast | 30 (4.0) | 3 (2.4) | 59 (5.9) | 12 (4.2) | ||

| Social class at birth: I-IIINM | 107 (14.4) | 20 (16.1) | 144 (14.5) | 50 (17.3) | ||

| IIIM-V | 594 (80.1) | 96 (77.4) | 0.79 | 788 (79.4) | 215 (74.4) | 0.18 |

| Forces/unclassified | 41 (5.5) | 8 (6.5) | 61 (6.1) | 24 (8.3) | ||

| Adult social class: I-IIINM | 308 (41.5) | 55 (44.4) | 430 (43.3) | 113 (39.1) | ||

| IIIM-V | 427 (57.6) | 68 (54.8) | 0.83 | 562 (56.6) | 176 (60.9) | 0.38 |

| Smoker status: Never | 254 (34.2) | 41 (33.1) | 627 (63.3) | 169 (58.5) | ||

| Ex | 385 (51.9) | 67 (54.0) | 268 (27.0) | 95 (32.9) | ||

| Current | 103 (13.9) | 16 (12.9) | 0.90 | 96 (9.7) | 25 (8.7) | 0.15 |

| Alcohol: ≤ 21/ ≤ 14 units per week men/women | 549 (80.8) | 95 (76.6) | 943 (95.0) | 271 (93.8) | ||

| >21/>14 units per week men/women | 142 (19.2) | 29 (23.4) | 0.27 | 50 (5.0) | 18 (6.2) | 0.43 |

P-values for differences in characteristics according to falls history obtained from 2-sample t-tests (for continuously distributed variables) or Chi-squared tests (for categorical variables).

Geometric means and SDs

Grip strength data missing for two men and three women. Height data missing for one man and two women.

Weight data missing for two men and one woman. Walking speed missing for one man. Adult social class unclassified for eight men and one woman. Smoking data missing for one woman. Alcohol data missing for one man.

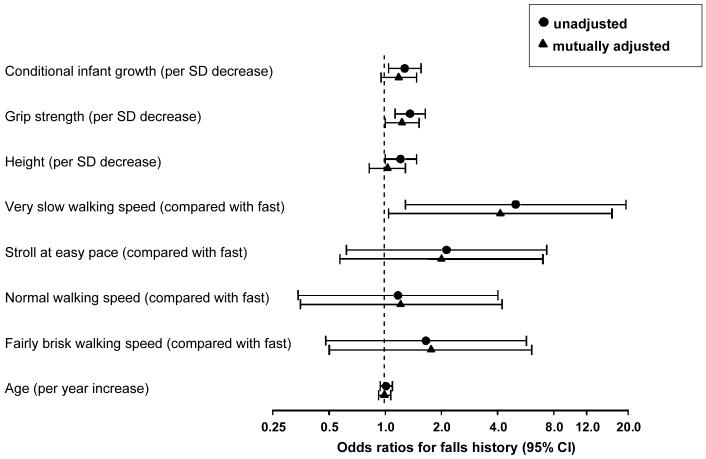

Multivariate analyses were used to investigate the relationship between falls history and conditional infant growth after adjustment for adult grip strength, height, age and walking speed in men, and after adjustment for adult grip strength, height, age, walking speed and body mass index in women. Among men, grip strength and walking speed remained strongly associated with a history of falls, but the relationships between conditional infant growth or adult height and falls history were attenuated (Table 2). Walking speed was the only characteristic associated with falls history in the mutually adjusted model for women (Table 2). Figure 1 displays the univariate and mutually adjusted odds ratios for falls history in men. Consideration of effect size in a sequence of three separate multivariate models for men (for conditional infant growth and grip strength, conditional infant growth and walking speed, and finally conditional infant growth and adult height as predictors of falls history) suggested that attenuation of the association between conditional infant growth and falls history was slightly greater after adjusting for grip strength than after adjusting for walking speed or adult height although all factors reduced the effect size (odds ratios for falls history per SD decrease in conditional infant growth were: 1.21 (95%CI 0.98, 1.48) p=0.08 adjusted for grip strength; 1.24 (95%CI 1.00, 1.52) p=0.05 adjusted for walking speed; and 1.23 (95%CI 0.99, 1.52) p=0.06 adjusted for adult height). There were no quadratic relationships between early growth and falls.

Table 2.

Hertfordshire Cohort Study: odds ratios for falls history in the past year in relation to early life and adult characteristics

| MEN | WOMEN | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Falls history in relation to: | Univariate OR | (95% CI) | p value | Mutually adjusted OR | (95% CI) | p value | Univariate OR | (95%CI) | p value | Mutually adjusted OR | (95% CI) | p value |

| Conditional infant growth (per SD decrease) | 1.27 | (1.04, 1.56) | p=0.02 | 1.18 | (0.95, 1.47) | p=0.13 | 1.11 | (0.97, 1.27) | p=0.13 | 1.08 | (0.94, 1.25) | p=0.27 |

| Grip strength (per SD decrease) | 1.36 | (1.13, 1.64) | p=0.001 | 1.23 | (1.00, 1.52) | p=0.05 | 1.18 | (1.04, 1.34) | p=0.01 | 1.06 | (0.92, 1.22) | p=0.43 |

| Height (per SD decrease) | 1.21 | (1.00, 1.47) | p=0.05 | 1.03 | (0.82, 1.28) | p=0.81 | 1.14 | (0.99, 1.30) | p=0.06 | 1.07 | (0.93, 1.24) | p=0.35 |

| BMI (per SD decrease) | not included | 1.17 | (1.03, 1.33) | p=0.02 | 1.06 | (0.92, 1.22) | p=0.43 | |||||

| Walking speed: | ||||||||||||

| Very slow | 5.00 | (1.28, 19.50) | 4.13 | (1.04, 16.43) | 3.28 | (1.55, 6.94) | 2.76 | (1.24, 6.14) | ||||

| Stroll at an easy pace | 2.13 | (0.62, 7.34) | 2.00 | (0.57, 6.99) | 2.00 | (1.02, 3.93) | 1.81 | (0.90, 3.66) | ||||

| Normal speed | 1.17 | (0.34, 4.02) | 1.21 | (0.35, 4.22) | 1.16 | (0.60, 2.23) | 1.08 | (0.56, 2.10) | ||||

| Fairly brisk | 1.65 | (0.48, 5.70) | 1.76 | (0.50, 6.10) | 1.21 | (0.61, 2.41) | 1.18 | (0.59, 2.35) | ||||

| Fast | Baseline p=0.008 for trend | Baseline p=0.05 for trend | Baseline p<0.001 for trend | Baseline p=0.001 for trend | ||||||||

| Age (per year increase) | 1.01 | (0.94, 1.09) | p=0.72 | 0.99 | (0.92, 1.07) | p=0.88 | 1.02 | (0.97, 1.07) | p=0.48 | 1.00 | (0.95, 1.05) | p=0.95 |

Figure 1.

Falls history in men in relation to conditional infant growth, adult grip strength, height, walking speed and age. Hertfordshire Cohort Study, 1998-2004. (CI - confidence interval, SD - standard deviation.)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an association between poor growth in early life and falls in older people. We have shown that lower conditional infant growth is significantly associated with a history of falls in older men. There was a similar but non-significant relationship in the women. However there was no relationship between birth weight and falls in either men or women. The other significant predictors of falls in this population were gender, height, grip strength, and walking speed. BMI was only associated with falling in the women and neither fat mass nor non-fat mass were related to falls in either gender. Age within the narrow range studied was not significantly associated with falls history in men or women.

Multivariate analyses allowed further investigation of the relationship between conditional infant growth and history of falls in the men. In particular, low social class was a potential alternative explanation for the relationship between poor early growth and increased falls. However social class, ascertained either at birth or in adulthood, was not related to history of falls and furthermore social class was not significantly associated with infant growth although there was a relationship with adult walking speed. The association was also not explained by height but was attenuated after adjustment for grip strength and walking speed. The contribution of low grip strength to the relationship between poor conditional infant growth and falls is consistent with findings from previous studies demonstrating a relationship between poor early growth and reduced adult muscle strength(21;23;24). It suggests that early environmental influences may not only result in long term impaired muscle function but also impact on the important clinical sequelae of falls. Supportive evidence for the link with falls comes from a study reporting an association between poor childhood growth and risk of hip fracture in later life(34). Sarcopenia and increased falls risk, as well as reduced bone mass, may lie on the causal pathway.

Associations between early growth and adult health have been explained by the phenomenon of programming which is the persisting influence of exposures occurring at critical periods of early development on long-term organ structure, function and regulation(35). Programming is an example of developmental plasticity which is the ability of a single phenotype to produce more than one alternative form of structure, physiological state or behaviour in response to environmental conditions(36). This enables the production of phenotypes that are better suited to their environment than would be possible if the same phenotype was produced regardless of environmental conditions(37). The consequences of developmental plasticity for human health were the subject of a recent paper(38).

Programming of muscle has been documented in animal models, for example in the field of animal husbandry where prenatal nutritional manipulation of muscle growth and quality is of particular interest to the meat industry. Prenatal undernutrition has been associated with reduced neonatal muscle weight but not fibre number in the sheep(39) and a reduction in postnatal muscle fibre number in the pig(40), guinea pig(41) and rat(42). There is evidence that these effects persist (43). There is evidence that the muscle phenotype can also be influenced by postnatal nutrition(44) and the observations from this study linking falls history with conditional infant growth rather than birth weight suggests that postnatal rather than prenatal influences on muscle growth and development may be more important for risk of falls in later life.

The relationship between conditional infant growth and falls appeared to be stronger in the men than in the women although there was no statistical evidence for different associations between the genders. Health care utilization is known to differ between men and women but the use of self-reported fall data in this study avoided information bias due to differential recording of falls in medical records. Gender differences in programming have been described previously, associated with differing growth trajectories and susceptibility to environmental influences between male and female fetuses (45). However there are also differences in adult body composition that may be relevant. Women have a lower muscle to fat ratio than men and the relatively lower proportion of muscle may attenuate associations between growth in early life and adult muscle function in women. The weaker although still significant relationship between grip strength and falls in women supports the concept that gender differences in body composition are relevant in understanding the differing patterns of associations.

There are a number of potential caveats to the interpretation of our findings. We did not have prospective falls data and had to use history of falls in the last year to characterise fallers. This approach can lead to under-reporting because of problems with recall but is unlikely to have affected differentially those with different patterns of early growth, so no observation bias should have been introduced. In contrast, response bias may have occurred because of losses to follow up which occurred during tracing and in gaining consent to participate. However we were able to address this by characterising those who did not take part in the study in a number of ways. There were no substantial differences in birth weight, weight at one year or conditional infant growth between subjects who were traced and eligible to participate in the study but did not, and those who had a home interview. Furthermore, there were no major differences in age, social class, alcohol consumption or activity level, between interviewed subjects who did or did not attend clinic.

The proportion of current smokers was lower among interview subjects who did come to clinic than those who declined suggesting that there may have been a ‘healthy subject’ effect in this study. However our comparisons were internal, therefore unless the relationship between early size and falls history differed between those who did and did not come to clinic, no bias should have been introduced(27). We used muscle strength rather than muscle mass to define sarcopenia. The latter approach has been reported more commonly in the literature but there is growing support for the use of strength because of its greater functional relevance to physical performance in older people(31).

The potential relevance of these findings to clinical practice needs to be considered. At the population level, poor early growth appears to be a risk factor for falls. Knowledge of early growth and muscle strength may contribute to risk stratification tools for the primary prevention of falls in the future. Greater understanding of the mechanisms underlying the association between early growth, sarcopenia and increased falls risk may also facilitate the development of beneficial interventions across the life course to preserve muscle function and prevent falls. Our findings support an association between poor growth in early life and falls in older men. This relationship appears to be mediated partly through sarcopenia. The weaker, non-significant association in women may reflect gender differences in body composition. The absence of a relationship with birth weight suggests that postnatal rather than prenatal influences on muscle growth and development may be important for risk of falls in later life.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N.Engl.J Med. 1988;319:1701–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masud T, Morris RO. Epidemiology of falls. Age Ageing. 2001;30:3–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.suppl_4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stel VS, Smit JH, Pluijm SM, Lips P. Consequences of falling in older men and women and risk factors for health service use and functional decline. Age Ageing. 2004;33:58–65. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scuffham P, Chaplin S, Legood R. Incidence and costs of unintentional falls in older people in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol.Community Health. 2003;57:740–4. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.9.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kannus P, Parkkari J, Niemi S, Palvanen M. Fall-induced deaths among elderly people. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:422–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention. J Am Geriatr.Soc. 2001;49:664–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wickham C, Cooper C, Margetts BM, Barker DJ. Muscle strength, activity, housing and the risk of falls in elderly people. Age Ageing. 1989;18:47–51. doi: 10.1093/ageing/18.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ory MG, Schechtman KB, Miller JP, et al. Frailty and injuries in later life: the FICSIT trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:283–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G, et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community [see comments] N Engl J Med. 1994;331:821–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinetti ME. Preventing falls in elderly persons. NEJM. 2003;348:42–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp020719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang JT, Morton SC, Rubenstein LZ, et al. Interventions for the prevention of falls in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 2004;328:680. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, Glucksman E, Jackson S, Swift C. Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial [see comments] Lancet. 1999;353:93–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregg EW, Pereira MA, Caspersen CJ. Physical activity, falls, and fractures among older adults: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:883–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kannus P, Khan KM. Prevention of falls and subsequent injuries in elderly people: a long way to go in both research and practice. CMAJ. 2001;165:587–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillespie L. Preventing falls in elderly people. BMJ. 2004;328:653–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiswell RA, Hawkins SA, Jaque SV, et al. Relationship between physiological loss, performance decrement, and age in master athletes. J Gerontol A Biol.Sci.Med Sci. 2001;56:M618–M626. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.10.m618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arden NK, Spector TD. Genetic influences on muscle strength, lean body mass, and bone mineral density: a twin study. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:2076–81. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.12.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seibert MJ, Xue QL, Fried LP, Walston JD. Polymorphic variation in the human myostatin (GDF-8) gene and association with strength measures in the Women’s Health and Aging Study II cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1093–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth SM, Schrager MA, Ferrell RE, et al. CNTF genotype is associated with muscular strength and quality in humans across the adult age span. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1205–10. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.4.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geusens P, Vandevyver C, Vanhoof J, Cassiman JJ, Boonen S, Raus J. Quadriceps and grip strength are related to vitamin D receptor genotype in elderly nonobese women. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:2082–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.12.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sayer AA, Syddall HE, Gilbody HJ, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Does sarcopenia originate in early life? Findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. J Gerontol. 2004;59A:930–4. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.9.m930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sayer AA, Syddall HE, Dennison EM, et al. Birth weight, weight at one year and body composition in older men: findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:199–203. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuh D, Bassey J, Hardy R, Aihie Sayer A, Wadsworth M, Cooper C. Birth weight, childhood size, and muscle strength in adult life: evidence from a birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:627–33. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sayer AA, Cooper C, Evans JR, et al. Are rates of ageing determined in utero? Age Ageing. 1998;27:579–83. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gale CR, Martyn CN, Kellingray S, Eastell R, Cooper C. Intrauterine programming of adult body composition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:267–72. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips DIW. Relation of fetal growth to adult muscle mass and glucose tolerance. Diab Med. 1995;12:686–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1995.tb00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syddall HE, Sayer AA, Dennison EM, Martin HJ, Barker DJ, Cooper C. Cohort Profile: The Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Int.J Epidemiol. 2005 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R, editors. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fidanza F. Anthropometric methodology. In: Fidanza F, editor. Nutritional status assessment. London: Chapman Hall; 1991. pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiner JS, Lourie JA, editors. International biology: a guide to field methods. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lauretani F, Russo CR, Bandinelli S, et al. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility: an operational diagnosis of sarcopenia. J.Appl.Physiol. 2003;95:1851–60. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00246.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durnin JV, Womersley J. Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: measurements on 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years. Br J Nutr. 1974;32:77–97. doi: 10.1079/bjn19740060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cole TJ. Conditional reference charts to assess weight gain in British infants. Arch.Dis.Child. 1995;73:8–16. doi: 10.1136/adc.73.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper C, Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Osmond C, Tuomilehto J, Barker DJP. Maternal height, childhood growth and risk of hip fracture in later life: a longitudinal study. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:623–9. doi: 10.1007/s001980170061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucas A. Programming by early nutrition in man. In: Bock GR, Whelan J, editors. The childhood environment and adult disease. Chichester: John Wiley; 1991. pp. 38–50. (Ciba Foundation Symposium 156). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aihie Sayer A, Barker D. The early environment, developmental plasiticity and aging. Rev Clin Geront. 2003;12:205–11. [Google Scholar]

- 37.West-Eberhard MJ. Phenotypic plasticity and the origins of diversity. Ann Rev Ecol Syst. 1989;20:249–78. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bateson P, Barker D, Clutton-Brock T, et al. Developmental plasticity and human health. Nature. 2004;430:419–21. doi: 10.1038/nature02725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenwood PL, Hunt AS, Hermanson JW, Bell AW. Effects of birth weight and postnatal nutrition on neonatal sheep: II. Skeletal muscle growth and development. J Anim Sci. 2000;78:50–61. doi: 10.2527/2000.78150x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dwyer CM, Stickland NC, Fletcher JM. The influence of maternal nutrition on muscle fiber number development in the porcine fetus and on subsequent postnatal growth. J Anim Sci. 1994;72:911–7. doi: 10.2527/1994.724911x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dwyer CM, Madgwick AJ, Ward SS, Stickland NC. Effect of maternal undernutrition in early gestation on the development of fetal myofibres in the guinea-pig. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1995;7:1285–92. doi: 10.1071/rd9951285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson SJ, Ross JJ, Harris AJ. A critical period for formation of secondary myotubes defined by prenatal undernourishment in rats. Development. 1988;102:815–21. doi: 10.1242/dev.102.4.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pond WG, Yen JT, Mersmann HJ, Maurer RR. Reduced mature size in progeny of swine severely restricted in protein intake during pregnancy. Growth Dev.Aging. 1990;54:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White P, Cattaneo D, Dauncey MJ. Postnatal regulation of myosin heavy chain isoform expression and metabolic enzyme activity by nutrition. Br J Nutr. 2000;84:185–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barker DJP. Mothers, babies and health in later life. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998. [Google Scholar]