Abstract

Promyelocytic leukemia (PML) is the organizer of nuclear matrix domains, PML nuclear bodies (NBs), with a proposed role in apoptosis control. In acute promyelocytic leukemia, PML/retinoic acid receptor (RAR) α expression disrupts NBs, but therapies such as retinoic acid or arsenic trioxide (As2O3) restore them. PML is conjugated by the ubiquitin-related peptide SUMO-1, a process enhanced by As2O3 and proposed to target PML to the nuclear matrix. We demonstrate that As2O3 triggers the proteasome-dependent degradation of PML and PML/RARα and that this process requires a specific sumolation site in PML, K160. PML sumolation is dispensable for its As2O3-induced matrix targeting and formation of primary nuclear aggregates, but is required for the formation of secondary shell-like NBs. Interestingly, only these mature NBs harbor 11S proteasome components, which are further recruited upon As2O3 exposure. Proteasome recruitment by sumolated PML only likely accounts for the failure of PML-K160R to be degraded. Therefore, studying the basis of As2O3-induced PML/RARα degradation we show that PML sumolation directly or indirectly promotes its catabolism, suggesting that mature NBs could be sites of intranuclear proteolysis and opening new insights into NB alterations found in viral infections or transformation.

Keywords: leukemia, interferon, ubiquitin, nuclear matrix, arsenic

Introduction

The promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene was initially characterized through its implication in the t(15;17) translocation specific for acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), which yields a PML/retinoic acid receptor (RAR) α fusion protein 1. A member of the RING-B-box-coiled-coil (RBCC) protein family, PML contains three zinc finger-like domains (a RING finger and two B boxes) and a coiled–coil dimerization domain. Although RBCC proteins have features of molecular adaptors, they have not been assigned a common function. Yet, the presence of a RING finger could point to an implication in ubiquitin conjugation 2. PML knockout mice are viable but susceptible to some infections and tumor development, possibly as the consequence of their apoptosis resistance 3 4. Conversely, PML overexpression was shown to induce growth arrest, apoptosis, or senescence 5 6 7 8. PML was proposed to modulate transcription through a direct interaction with CBP, Daxx, and/or another RBCC family member, TIF1α 9 10 11 12. A number of PML isoforms are generated through alternative splicing in the 3′ region mRNA 13.

A fraction of PML is nucleoplasmic, the rest being located on discrete subnuclear matrix-associated structures, the PML nuclear bodies (NBs; 14 15 16 17 18). PML appears to be the organizer for NBs, targeting proteins such as Sp100, CBP, or Daxx onto these domains 19 20. Disruption of PML NBs has been observed in a variety of disease processes such as neurodegenerative disorders, virus infections, or APL 18. In the latter, PML/RARα expression dominantly delocalizes NB-associated proteins towards microspeckles. Exposure to two therapeutic agents, retinoic acid (RA) or arsenic trioxide (As2O3), results in the degradation of the PML/RARα fusion and accordingly restores NB structure, linking NBs integrity to disease status. PML delocalization by PML/RARα promotes apoptosis resistance, while NB targeting of PML favors cell death 5 8. Similarly, the wild-type PML alleles oppose leukemogenesis in PML/RARα transgenic mice 21.

PML is covalently modified by SUMO-1, a ubiquitin-like polypeptide also known as sentrin-1, UBL-1, or PIC-1. SUMO-1 can be conjugated onto a variety of proteins including p53, IκB, Sp100, PML, and RanGAP. Like ubiquitin, SUMO-1 covalently binds lysine residues of target proteins in an ATP-dependent reaction requiring the E2-conjugating enzyme UBC9. In the case of RanGAP-1, the unmodified protein is cytoplasmic, while sumolated RanGAP-1 binds to the nuclear pore 22. For IκB, SUMO-1 appears to compete with ubiquitin for modification of the same target lysine, inhibiting proteasome-dependent IκB degradation 23. Thus, SUMO-1 seems to modulate the conformation of its target proteins rather than induce their degradation. Three major sites of SUMO-1 modification were identified in PML: K65 in the RING finger; K160 in the first B-box; and K490 in the nuclear localization signal (NLS; references 24 and 25). It was strongly suggested that these modifications, which are rapidly enhanced by As2O3, are critical for PML targeting onto the nuclear matrix and recruitment of NB-associated proteins 10 20 26, which in turn, was suggested to contribute to apoptosis induction 27 or transcriptional regulation 28.

As2O3-induced PML/RARα degradation is the likely basis of its clinical efficacy in APL. We demonstrate that As2O3 induces sumolation and proteasome-dependent degradation of PML or PML/RARα. A single SUMO conjugation site in PML is required for the formation of “mature” shell-like bodies and proteasome recruitment as well as PML degradation, providing the first examples of both SUMO-promoted degradation and NB-associated proteolysis.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Mutagenesis.

His tag (C ATG CAT CAC CAC CAT CAC CAT TC) and SV40-NLS (C ATG GCGCT CCC AAA AAG AAA AGA AAG GT) annealed oligonucleotides were cloned into the ATG-NcoI site of PML-pSG5 plasmid. K-A(65/67) and K-R(487/490) PML mutants were cloned into His-(NLS)-PML-pSG5 plasmids. COOH-terminal deletions and mutagenesis were performed on His-(NLS)-PML-pSG5 plasmids using a pfuTurbo DNA polymerase mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Wild-type K-R(160), K-R(160/490) (2K), and K-R(65/160/490) (3K) PML mutants were cloned in pcDNA4 (Invitrogen) for tetracycline inducible PML−/− cell transfection and in MSCVneo plasmid for retroviral infections. Ubiquitin gene was tagged by influenza hemagglutinin (HA) in pSG5 plasmid.

Cell Lines, Cell Culture, and Transfections.

Cells were cultured in 10% FCS DMEM media (GIBCO BRL) with an appropriate selection of G418, hygromycin, zeomycin, and blasticidine. Transfection assays were performed with fugene 6 liposomes (Roche). Mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from PML−/− animals were immortalized with a plasmid expressing SV40 large T antigen. A stable cell line expressing PML under the transcriptional dependence of the Tet-on system (Invitrogen) was then derived by successive expression of the hybrid Tet repressor (pcDNA6/TR) (coupled to blasticidin resistance) and pcDNA4/PML (coupled to zeocin resistance). A 280-mM As2O3 stock (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared by dissolving the powder in 1 M NaOH, then 1 mM solution was prepared in Tris-buffered saline. Lactacystin (Affiniti Research Products) was used at 10 μM overnight, while leptomycin B (LMB) was used at 2 μM. Recombinant retroviruses expressing PML or PML/RARα were produced by transient transfection of BOSC packaging cells. Then, filtered supernatant was used for infection of NIH3T3 cells or PML−/− MEF cells followed by neomycin selection.

Antibodies, Western Blot Analysis, Immunofluorescence, and Electron Microscopy.

A mix of 5E10 and PG-M3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) monoclonal antibodies was used for immunofluorescence. The monoclonal anti–SUMO-1 antibodies (mouse monoclonal anti–GMP-1 antibody) was obtained from Zymed Laboratories, while anti–SUMO-2 was a gift from M. Matunis (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). The monoclonal anti-Ha used is the clone 16B12 (Babco). The rabbit polyclonal antibody against proteasome 20S “core” and against 11S regulator subunit α and β (PA28) are produced by Affiniti Research Products. One anti-Daxx monoclonal antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (M-112 clone) and the other was provided by G. Grosveld (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN). The A-22 anti-CBP polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was used in immunofluorescence assay and C-20 for Western blot analysis.

For immunofluorescence analysis, cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde for anti-PML, anti–SUMO, anti-HA, anti-CBP, anti-Daxx antibodies, and in acetone for anti-proteasome 20S and 11S. Cell extracts were prepared by boiling PBS-washed cells in Laemmli buffer. Proteins were separated by 8–10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, blocked in 10% milk for 2 h, and then incubated overnight with the first antibody at 4°C and 1 h with the second antibody at room temperature. For electron microscopy, cells were fixed at 4°C in 1.6% glutaraldheyde or 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and then extensively washed in 0.1 M phosphate Sörensen buffer, pH 7.2–7.3. The fixed material was embedded in Lowricryl K4M as described previously.

Immunoprecipitation, His Purification, and Cell Fractionation.

His-tagged PML proteins were purified using Talon metal affinity resin (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) in denaturing conditions, as suggested by the manufacturer. For cell fractionation, cells were lysed in RIPA. After brief sonication and centrifugation, Laemmli buffer was added to the supernatant (RIPA fraction), and the pellet was washed twice and resuspended by boiling in Laemmli buffer (pellet fraction).

Results

Arsenic Triggers both SUMO Conjugation and Proteasome-dependent Degradation of PML within the Nucleus.

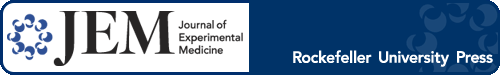

PML/RARα degradation by As2O3 is dependent on its PML moiety 29. PML can undergo a variable degree of SUMO-1 modification 25 26 30. We confirm that in cells stably overexpressing a specific PML isoform 1 at least three distinct proteins reactive with PML and SUMO-1, as well as SUMO-2, were found above the 90-kD parental PML band (Fig. 1 a). A 1-h treatment with 10−6 M As2O3 induce a dramatic shift towards the SUMO reactive PML proteins, accompanied by a corresponding decrease in unmodified PML 26 29. A longer As2O3 treatment (8–24 h) of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, HeLa, U373, or MEF cells overexpressing PML leads to a drastic decrease in the total amount of PML proteins. Unmodified PML disappear and only high molecular mass SUMO-modified species (∼220 kD) remain (Fig. 1 b, and data not shown). This reflects PML degradation rather than the inefficient detection of high molecular weight PML–SUMO complexes because in some experiments the abundance of these complexes also decreases after As2O3 exposure (Fig. 1 c and 2 b, and data not shown). Such loss of PML can be reversed by the proteasome inhibitors lactacystin (Fig. 1 b) or MG132, neither of which interfere with the sumolation process (data not shown), implicating proteasomes in As2O3-induced PML degradation.

Figure 1.

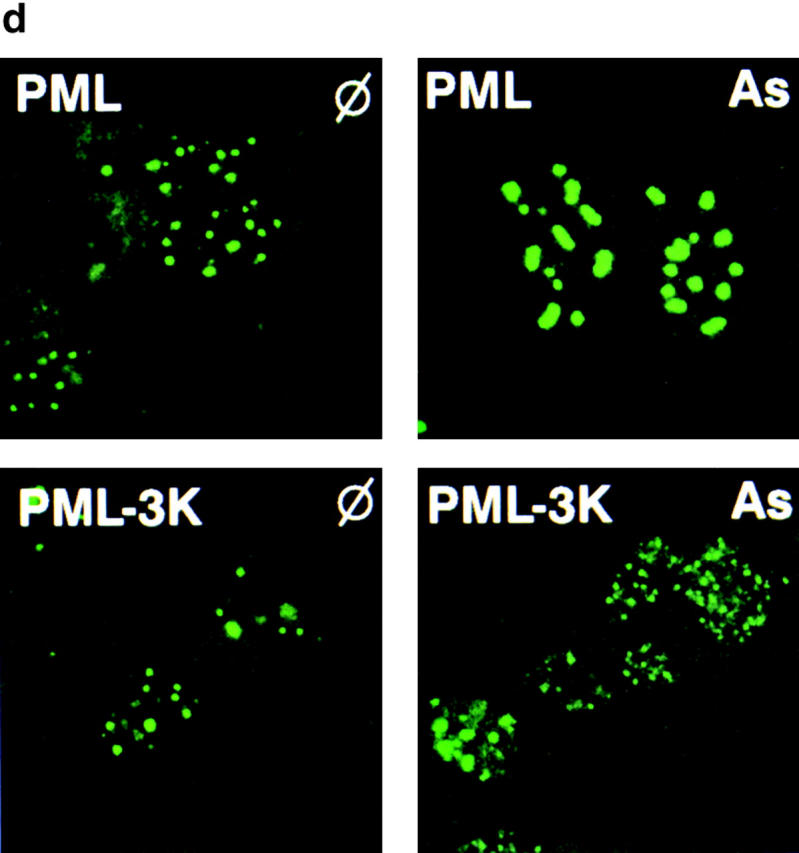

Arsenic induces SUMO modification and proteasome-dependant degradation of PML. (a) Western blot analysis of His-purified proteins from His-PML-CHO cells treated or not with 1 μM As2O3 overnight and revealed with anti-PML antibodies (left), with anti–SUMO-1 antibodies (middle), or anti–SUMO-2 antibodies (right). (b) Western blot analysis performed on whole CHO–PML extract revealed with anti-PML and anti-actin antibodies. Cells were treated overnight with 1 μM As2O3, 10 μM lactacystin (L), both (L/As), or none (φ). SUMO-modified PML species are indicated. (c) HeLa cells were treated for 48 h with IFN-α or -γ, with or without an overnight As2O3 treatment. PML isoforms induced by IFN are degraded after As2O3 treatment (top), whereas Sp100 isoforms are not degraded (bottom). (d) PML–CHO cells were treated or not with 1 μM As2O3 and 10 nM LMB for 12 h.

PML and Sp100 genes are primary IFN-inducible target genes 31. As for the specific PML isoform studied above, all endogenous PML isoforms expressed in IFN-treated HeLa cells were degraded upon an overnight As2O3 treatment, while Sp100 was not (Fig. 1 c). Some nuclear proteins are degraded in the cytoplasm. PML has been shown to undergo exportin 1–mediated export 32. CHO–PML cells were thus exposed to As2O3 and/or to the nuclear export inhibitor LMB for 12 h. LMB increased PML NB-associated fluorescence (data not shown) but did not block (and even enhanced) As2O3-induced PML degradation (Fig. 1 d). Therefore, As2O3 treatment triggers PML sumolation coupled to its proteasome-dependent catabolism within the nucleus.

Distinct Isoform-specific Sequences Are Required for As2O3-triggered PML Degradation.

In our working isoform 1, deletion analysis showed that five repeats of a LASPL motif (amino acid 594–615), a COOH-terminal sequence, are required for As2O3-induced degradation (Fig. 2). Mutants without these repeats were consistently expressed at a higher level than the parental protein (Fig. 2 b), suggesting that this sequence acts as both a constitutive and an As2O3-dependent degradation signal. The core common to all isoforms (PML1-571) is not degraded upon As2O3 exposure (Fig. 2 b), while all endogenous PML isoforms (Fig. 1 c) or overexpressed ones (PML-4 [13], Fig. 2 b, and PML-1, -2, -3 not shown) are degraded. In one of these isoforms a LASPL repeat is required for PML catabolism, but we have not pinpointed the residues required for degradation of the other isoforms. Many RBCC proteins contain specific interaction domains in their COOH terminus (see Discussion). Sensitivity to As2O3-triggered degradation conferred by distinct isoform-specific sequences could suggest that their common function is to interact with proteins involved in PML catabolism.

Figure 2.

The COOH terminal part of PML proteins is required for their As2O3-induced degradation. (a) Schematic representation of As2O3-induced degradation of different PML mutants and another isoform (PML-4). (b) Western blot analysis of some of the mutants depicted above with or without an overnight 1 μM As2O3 treatment. Unsumolated PML proteins are indicated by arrows. PML mutants were stably expressed in CHO cells from pSG5 expression vectors.

As2O3-induced Catabolism of PML or PML/RARα Requires the K160 Sumolation Site.

Arsenic promotes both PML sumolation and its degradation. To address the role of sumolation in degradation, we mutated the three target lysines K65, K160, and K490 of PML, yielding the PML-3K mutant. Since K490 is essential for NLS function 25, the SV40 NLS was fused to the NH2-terminal end of PML. No evidence for the formation SUMO-modified PML-3K could be obtained by Western blots or fluorescence, even upon As2O3 treatment (Fig. 3 a, and data not shown). PML-3K was stably expressed either in CHO cells or in SV40(T)-immortalized PML−/− fibroblasts under the transcriptional control of a tetracycline-on promoter. Strikingly, in both systems, As2O3 treatment no longer induced the degradation of PML-3K (Fig. 3 a). However, a clear increase in PML-3K expression was observed upon lactacystin exposure (Fig. 3 a), suggesting that these three lysines are not major ubiquitination sites. Therefore, PML-3K can still be targeted by the ubiquitin/proteasome system in contrast to the sumolation mutant of IκBα.

Figure 3.

SUMO modification of K160 is required for As2O3-induced PML and PML/RARα degradation. (a) When stably expressed in CHO cells, PML-3K is not degraded upon an overnight As2O3 (As) exposure but upregulated by lactacystin (L) treatment. (b) SUMO modification of K160R and K490R PML mutants stably overexpressed in CHO treated with 1 μM As2O3 for 1 h were analyzed by Western blot analysis. (c) A longer As2O3 exposure (12 h) induces degradation of wild-type PML and K490R mutant, but not K160R. (d) Mutation of K160 in PML/RARα abolishes As2O3-induced degradation (12-h treatment) in retrovirally transduced NIH3T3 cells. This Western blot was revealed with an anti-RARα antibody.

Mutation of K490 shifted the SUMO ladder towards lower molecular weights with the loss of a single SUMO conjugate. Mutation of K65 did not change the pattern of PML conjugation before or after As2O3 exposure (data not shown). Since K65 is not part of a SUMO modification consensus sequence 25, it is unlikely to be a SUMO conjugation site. In contrast, when K160 was mutated, a single SUMO conjugate remained and PML sumolation became completely As2O3 insensitive (Fig. 3 b). This single sumolated PML protein is modified on K490 since it was lost upon mutation of this site (data not shown). We conclude that PML harbors two independent sumolation sites with distinct properties, with only SUMO conjugation of K160 triggering the formation of higher molecular mass PML adducts. Then, we examined the effect of an overnight As2O3 exposure (Fig. 3 c). Mutation of K160, but not that of K65 or K490, abolished PML degradation linking the presence of high molecular weight PML adducts with its catabolism. Ubiquitin could never be detected in these complexes, even after As2O3 treatment, lactacystin exposure, and adduct purification under denaturing conditions (data not shown). Moreover, these complexes are highly reactive with SUMO-1 and -2 suggesting that they may contain more than two SUMO molecules.

As2O3 induces the degradation of the APL-specific PML/RARα oncoprotein 26 29 33 in a lactacytin or MG132 reversible manner 34. To test the hypothesis that this sumolation site plays a role in PML/RARα degradation, we stably expressed in NIH3T3 cells PML/RARα or a mutant bearing a K to R mutation on K160 using retroviral transfer (Fig. 3 d). Mutation of K160 modified the sumolation pattern of PML/RARα and abolished its As2O3-induced degradation, strongly suggesting that the molecular mechanisms involved are similar to those outlined for PML.

Resistance of PML-3K to As2O3-induced Catabolism Does Not Reflect Its Inability to be Targeted to the Nuclear Matrix.

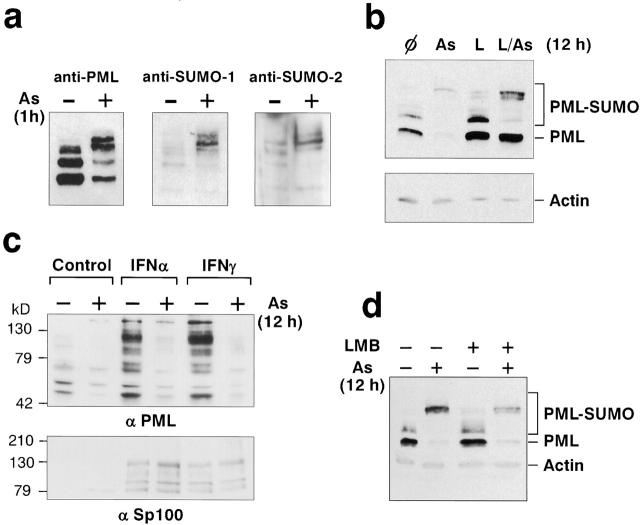

Arsenic exposure shifts PML towards the matrix (assessed by the RIPA insoluble fraction) as early as 1 h (Fig. 4 a, lane 4; references 26 and 29). After 12 h, only a small amount of the SUMO-modified PML remains in the matrix as the consequence of As2O3-triggered degradation (Fig. 4 a, lane 6). Combining lactacystin to As2O3 led to a sharp increase in the amount of matrix-bound PML (Fig. 4 a, lane 10) consistent with the idea that degradation occurs on the nuclear matrix.

Figure 4.

SUMO modification of PML is dispensable for PML matrix transfer induced by As2O3. (a) CHO–PML were treated with As2O3 for 1 h (As1h), for 12 h (As), and/or with lactacystin for 12 h (L and L/As). Proteins were fractionated into RIPA (R) or pellet (P) fractions before Western blot analysis (lanes are indicated). (b–d) PML−/− MEF stably transfected wild-type PML or PML-3K mutant were analyzed after a 1-h As2O3 treatment. (b) Note the As2O3-induced matrix transfer of PML-3K. (c) As2O3-induced matrix targeting of PML-3K is blocked by pretreatment with okadaic acid. Okadaic acid induces an additional, likely a phosphorylated, PML species. (d) Immunofluorescence analysis of in situ nuclear matrix preparation from PML−/− cells stably expressing wild-type PML or PML-3K mutant. Note the As2O3-induced aggregation of NBs for PML, but not for the PML-3K mutant, which remains in distinctly smaller aggregates.

Since SUMO conjugation of PML was proposed to trigger its matrix association 26, failure of PML-3K to degrade may reflect its inability to be matrix targeted. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the matrix association of PML-3K in both CHO and PML−/− cells. Upon a 1-h As2O3 exposure, a sharp transfer was observed from the RIPA soluble fraction to the insoluble one, for both PML and PML-3K (Fig. 4b and Fig. c, and data not shown). Using a more stringent criteria of nuclear matrix association (nuclear matrix preparations in situ; reference 35), we demonstrate that the PML-3K mutant localized to the nuclear matrix even before As2O3 exposure and is further shifted to the matrix after As2O3 treatment (Fig. 4 d). Therefore, PML binding to the nuclear matrix does not depend on SUMO, and the failure of PML-3K to be degraded upon As2O3 exposure is not the consequence of a defective matrix transfer.

Since sumolation is not implicated in matrix association, As2O3 could target PML to the matrix by modulating its phosphorylation. To test this hypothesis, PML-3K–expressing cells were exposed to As2O3 with or without the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid. Remarkably, okadaic acid could abrogate As2O3-induced matrix targeting of PML-3K (Fig. 4 c), strongly suggesting that PML dephosphorylation controls its matrix association. Since PML sumolation is influenced by its phosphorylation status 26 36 As2O3 could control PML sumolation indirectly through its phosphorylation.

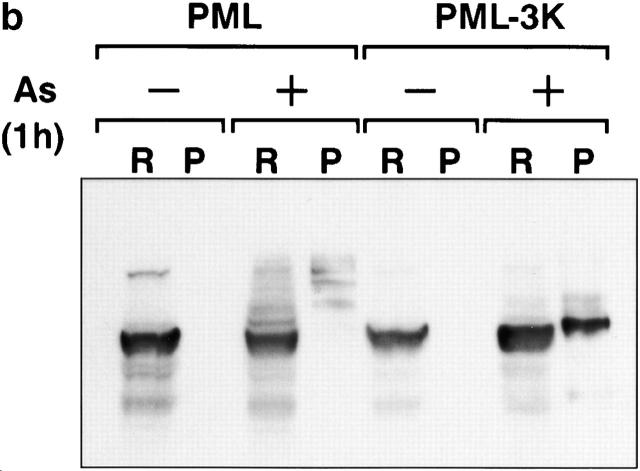

Role of Sumolation in As2O3-induced Changes in PML or PML/RARα Localization.

Then we analyzed NB formation in cell lines stably expressing PML-3K in a CHO or MEF(T)PML−/− background. Compared with wild-type PML, structures formed by PML-3K tend to be smaller and heterogeneous in size but otherwise appear normal in their number and distribution (Fig. 4 d). However, electron microscopic examination revealed a striking difference between the structures formed by PML and PML-3K. In the absence of sumolation, NBs never appeared as empty spheres with a PML-negative, electron light core 14, but rather as dense aggregates dispersed through the nucleoplasm (Fig. 5). When cells expressing PML-3K were treated with As2O3, no major qualitative change was observed but the number of aggregates increased (Fig. 4 d). This is in sharp contrast to structures formed by PML, which upon As2O3 treatment become very large bodies (Fig. 4 d) consisting of concentric circles of fibrillar material 29. We conclude that while SUMO-1 modification is dispensable for the formation of primary nuclear matrix aggregates, it is required for the formation of mature NBs and implicated in their morphological changes induced by As2O3. When expressed in NIH3T3 cells, both PML/RARα and PML/RARα–K160R displayed the same microspeckled pattern (data not shown), demonstrating that sumolation is not important for the localization of PML/RARα. As expected, As2O3 exposure did not affect the localization of PML/RARα–K160R, whereas PML/RARα was shifted towards NBs.

Figure 5.

SUMO modification of PML is required for mature NBs formation. Electronic microscopy examination of PML−/− MEF stably expressing PML (a) or PML-3K mutant (b). Note that small dense aggregates are formed by PML-3K, whereas standard PML empty structures where PML forms a distinct outer rim are observed upon expression of wild-type PML (reference 14).

PML Recruitment of the 11S Proteasome Complex Is SUMO Dependent.

Since As2O3-triggered PML degradation is coupled to its NB targeting and appears to be proteasome dependent, we analyzed the localization of the proteasome in this setting. In CHO–PML cells, PML partially colocalized with the α and β subunits of 11S, the regulatory complex of the proteasome (Fig. 6, and data not shown). Strikingly, As2O3 or lactacystin greatly increased this colocalization on larger speckles, and lactacystin/As2O3 combination induced the formation of very large and bright 11Sα- and β-positive speckles (Fig. 6, and data not shown). Colocalization of PML and the 20S core was observed in rare cells only after As2O3 exposure (Fig. 6). In untransfected CHO cells, little or no effect of these two drugs on 11S proteasome localization was observed (data not shown) implying a direct role of PML to recruit this complex.

Figure 6.

11S proteasome is recruited by PML onto NBs. Confocal analysis of PML and various proteasome components were realized on PML overexpressing CHO treated for 1 h by As2O3 (As), lactacystin (L), none (φ), or both (L/As). Localization of the endogenous 20S core and 11Sα, or β regulatory subunits of the proteasome are compared with that of PML as indicated.

Then we examined the sumolation requirements for proteasome recruitment onto NBs. Importantly, stably expressed PML-K160R failed to recruit the 11S proteasome components upon As2O3 exposure, whereas PML-K490R did (Fig. 7, and data not shown). This is consistent with the requirement of the K160 conjugation site for As2O3-induced degradation. As previously shown, PML-3K was unable to recruit Daxx or Sp100 19 20, but both PML and PML-3K similarly recruited CBP (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

PML-3K still recruits CBP, but not Daxx or Sp100, while PML-K160R fails to recruit 11Sα proteasome upon As2O3 exposure. Immuno-fluorescences were performed on PML−/− MEFs transiently transfected with wild-type PML or PML-3K mutant, stained with anti-PML, anti-Sp100, anti-Daxx, and monoclonal anti-CBP antibodies (top). PML−/− MEF cells infected with a PML or PML-K160R–expressing retrovirus were treated with As2O3 for 1 h and stained with PML or anti-11Sα antibodies as indicated (bottom). Note that 11Sα does not colocalize with PML-K160R.

Accumulation of PML fluorescence on nuclear dots when As2O3-induced PML degradation was blocked by lactacystin could suggest that degradation occurs on NBs. Similarly, when NB4 APL cells were exposed to As2O3, RARα fluorescence was detected on NB-like structures and was greatly enhanced by pretreatment with lactacystin (Fig. 8, and data not shown). These observations imply that As2O3 triggered PML/RARα degradation also occurs on NBs, in contrast to that induced by RA (Fig. 8; reference 37). Altogether, mature PML NBs appear to be the sites of PML and PML/RARα degradation, most likely through the SUMO-dependent recruitment of proteasome components.

Figure 8.

As2O3 targets PML/RARα onto NBs during As2O3-induced but not RA-induced degradation. NB4 cells were exposed to 1 μM As2O3 or RA for 6 and 24 h, respectively, before immunofluorescence, as indicated.

Discussion

Genesis of PML NBs.

The dramatic effect of As2O3 to recruit PML onto NBs lends considerable support to the idea that most of PML is not NB bound 26 29 38. Contrasting with previous proposals 26, we demonstrate that PML targeting onto the nuclear matrix is not SUMO dependent. Rather, PML traffic from the nucleoplasm to NBs involves two distinct steps that can be separated by both morphological and biochemical criteria: formation of primary nuclear matrix–associated bodies and NB maturation (Fig. 9). The matrix targeting of PML or PML-3K is likely regulated by a dephosphorylation event. PML dephosphorylation could trigger PML multimerization and promote the formation of the primary aggregates. Two previous studies had linked PML sumolation to its phosphorylation: calyculin A, another phosphatase inhibitor, was shown to block As2O3-triggered PML sumolation 26; and in the M phase of the cell cycle, PML is specifically phosphorylated and completely desumolated (36, and unpublished results). The major difference between PML and PML–SUMO bodies is their “apparent content” as detected by electron microscopy. Interestingly, in mature PML NBs, PML forms the outer shell and many proteins (Sp100, CBP) are found within its electron clear core (39, and unpublished results). Therefore, the SUMO-mediated maturation process is coupled to the recruitment of interacting proteins and their internalization. In conclusion, PML traffic from the nucleoplasm to mature NBs involves two distinct steps: an As2O3-triggered and phosphorylation-dependent aggregation on the matrix, followed by a SUMO-dependent maturation with protein recruitment (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of PML traffic onto NBs. Under our working model, PML is initially dispersed in the nucleoplasm possibly in the chromatin. A specific dephosphorylation event triggered by As2O3 targets PML to the nuclear matrix on primary PML bodies. Sumolation then induces the maturation to secondary PML bodies that contain the 11S proteasome subunits α and β, Daxx, and Sp100, where PML would be degraded.

Molecular Determinants of PML and PML/RARα Degradation.

Of the three putative SUMO binding sites, only two (K160 and K490) fit the (I/L)KXE consensus 25. These two sites are independent and appear not to play similar roles. Sumolation of K490 may play a role in PML nuclear import, while K160 controls 11S αβ proteasome recruitment and As2O3-induced PML degradation. Sumolation of K160, but not K490, triggers a set of covalent modifications that yields high molecular weight PML complexes whose presence is consistently associated with PML degradation. Several hypotheses can be put forward as to the mechanism of degradation. Either catabolism is the direct consequence of K160 sumolation or competition exists between SUMO and ubiquitin for this site. Under this last hypothesis, unsumolated PML would be the target for degradation, which could be consistent with its stabilization by lactacystin (Fig. 1 b). Yet, the kinetics of PML degradation do not favor this model because massive sumolation precedes degradation (Fig. 1, Fig. 3, and Fig. 4). Sumolation of K160 may also trigger PML ubiquitination elsewhere, but our attempts to identify ubiquitin in PML–SUMO complexes have been repeatedly unsuccessful. The transient presence of 20S and the accumulation of PML or PML/RARα on NBs upon As2O3/lactacystin exposure, as well as the failure of PML-K160R to recruit the proteasome and be degraded, are all consistent with the idea that degradation occurs on mature NBs. Altogether, our data provide the first example where sumolation directly or indirectly promotes protein degradation in a defined subnuclear compartment.

All PML isoforms are degraded in response to As2O3, yet their common moiety is not. With the restriction that the latter is consistently expressed at higher levels than the full-size isoforms and might saturate a rate-limiting degradation pathway, we conclude that isoform-specific sequences convey sensitivity to As2O3. Some well-characterized domains have been identified in the COOH terminus of RBCC proteins (such as the PHD/TTC or bromodomain in TIF1 or the butyrophylin domain in RFP), which are lost in oncogenic fusions. Therefore, ability to promote PML degradation in the presence of As2O3 constitutes the first common property of these regions. In PML/RARα, the RARα moiety, which was shown to specifically bind a 19S proteasome component SUG-1 40, may substitute for the PML COOH termini to confer sensitivity to As2O3-induced degradation.

PML/RARα degradations induced by As2O3 or RA, while both proteasome dependent, have distinct mechanisms. RA-induced degradation is dependent on RARα AF2, occurs on microspeckles (Fig. 8; reference 37), and likely is a postactivation mechanism 34. Arsenic-induced PML/RARα degradation is SUMO dependent, occurs on NBs, and is a very early effect. Since As2O3, in contrast to RA, does not activate transcription through PML/RARα, degradation of the fusion protein could account for its therapeutic effect. Therefore, it would be most interesting to test both the leukemogenic potential of PML/RARα-K160R and a putative response to As2O3.

Are NBs General Sites of Intranuclear Proteolysis?

RING finger proteins are proposed to act as E3 ubiquitin ligases and hence participate in protein degradation 2. Mature NBs whose formation is dependent on a RING-containing protein, namely PML, and interact with a proteasome complex, could be sites of protein degradation. The function of the 11S complex is ill-understood. It seems to play a role both in feeding the 20S proteasome core–misfolded proteins for degradation in a ubiquitin-independent manner and in proteolysis before MHC presentation. A role of the 11Sαβ complex in Hsp90-dependent protein refolding was also proposed 41. Through either of these functions, the 11S complex could play a role in the recruitment of the NB-associated proteins and account for their number and surprising variety. Sumolation of PML induces proteasome recruitment. In that respect, the function of several proteins involved in degradation complexes is enhanced when they become modified by SUMO or Nedd8 42.

The α and β components of the 11S complex are, like PML and several NB-associated proteins, direct transcriptional targets of IFN-γ. A link between immunoproteasome and PML NBs has very recently been proposed 43. In that sense, the highest levels of PML expression are found in macrophages, cells specialized in antigen presentation 15 44. A chimeric protein known to be misfolded has been shown to accumulate in PML NBs in a lactacystin-dependent manner and after lactacystin retrieval, the cleaved peptides became exposed on the MHC 45. That a PML mutant suppresses CTL-dependent tumor rejection 46 and PML−/− animals show an immune defect 4 could all be consistent with a functional relation between PML and antigen presentation.

A number of transcription factors can be targeted onto NBs upon PML expression. CBP could mediate recruitment of these factors onto NBs, possibly through tripartite CBP/PML/X complexes. Like MDM2, which uses CBP to target p53 for degradation 47, PML and CBP could cooperate to enhance both transcription and catabolism. Similarly, the immediate early HSV-1 ICP0 gene localizes to NBs, enhances transcription, and induces proteasome-dependent degradation of specific cellular proteins 48 49 50, providing another intriguing association between NBs, proteolysis, and transcriptional activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Melchior and L. Gerace for providing us with anti–SUMO-1 antibodies at the early stages of this project, M. Matunis for anti–SUMO-2 antibodies, and A. Guiochon-Mantel for advice. We thank the Lab Photo Hemato for their help with the figures, C. Lavau for material and advice on retroviral vectors, M. Yoshida (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan) for LMB, M. Gianni for the first experiments on proteasome inhibitors, M. Schmitt for confocal microscopy, and Z. Doubeikovsky for antibody purification.

This work was supported by grants from the Fondation St. Louis and the European Economic Community. J. Zhu was supported by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer and Fondation de France, and V. Lallemand-Breitenbach by the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer and the French Ministry of Research.

Footnotes

V. Lallemand-Breitenbach and J. Zhu contributed equally to this work.

This work was presented at the Cold Spring Harbor meeting on “Dynamic Organization of Nuclear Function” on September 13–17, 2000.

Abbreviations used in this paper: APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; HA, hemagglutinin; LMB, leptomycin B; MEF, mouse embryo fibroblast; NB, nuclear body; NLS, nuclear localization signal; PML, promyelocytic leukemia; RA, retinoic acid; RAR, RA receptor; RBCC, RING-B-box-coiled-coil.

References

- de Thé H., Lavau C., Marchio A., Chomienne C., Degos L., Dejean A. The PML-RARα fusion mRNA generated by the t(15;17) translocation in acute promyelocytic leukemia encodes a functionally altered RAR. Cell. 1991;66:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90113-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freemont P.S. RING for destruction? Curr. Biol. 2000;10:R84–R87. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.-G., Ruggero D., Ronchetti S., Zhong S., Gaboli M., Rivi R., Pandolfi P.P. PML is essential for multiple apoptotic pathways. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:266–272. doi: 10.1038/3073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.G., Delva L., Gaboli M., Rivi R., Giorgio M., Cordon-Cardo C., Grosveld F., Pandolfi P.P. Role of PML in cell growth and the retinoic acid pathway. Science. 1998;279:1547–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quignon F., de Bels F., Koken M., Feunteun J., Ameisen J.-C., de Thé H. PML induces a caspase-independent cell death process. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:259–265. doi: 10.1038/3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson M., Carbone R., Sebastiani C., Cioce M., Fagioli M., Saito S., Higashimoto Y., Appella E., Minucci S., Pandolfi P.P., Pelicci P.G. PML regulates p53 acetylation and premature senescence induced by oncogenic Ras. Nature. 2000;406:207–210. doi: 10.1038/35018127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbeyre G., de Stanchina E., Querido E., Baptiste N., Prives C., Lowe S.W. PML is induced by oncogenic ras and promotes premature senescence. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2015–2027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S., Salomoni P., Ronchetti S., Guo A., Ruggero D., Pandolfi P.P. Promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) and Daxx participate in a novel nuclear pathway for apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:631–639. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiochon-Mantel A., Savouret J.F., Quignon F., Delabre K., Milgrom E., de Thé H. Effect of PML and PML-RAR on the transactivation properties and subcellular distribution of steroid hormone receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 1995;9:1791–1803. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.12.8614415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S., Delva L., Rachez C., Cenciarelli C., Gandini D., Zhang H., Kalantry S., Freedman L.P., Pandolfi P.P. A RA-dependent, tumour-growth suppressive transcription complex is the target of the PML-RARα and T18 oncoproteins. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:287–295. doi: 10.1038/15463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Leo C., Zhu J., Wu X., O'Neil J., Park E.J., Chen J.D. Sequestration and inhibition of daxx-mediated transcriptional repression by PML. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:1784–1796. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1784-1796.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucas V., Tini M., Egan D.A., Evans R.M. Modulation of CREB binding protein function by the promyelocytic (PML) oncoprotein suggests a role for nuclear bodies in hormone signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2627–2632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi P.P., Alcalay M., Fagioli M., Zangrilli D., Mencarelli A., Diverio D., Biondi A., Lo Coco F., Rambaldi A. Genomic variability and alternative splicing generate multiple PML/RARα transcripts that encode aberrant PML proteins and PML/RARα isoforms in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. EMBO J. 1992;11:1397–1407. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koken M.H.M., Puvion-Dutilleul F., Guillemin M.C., Viron A., Linares-Cruz G., Stuurman N., de Jong L., Szostecki C., Calvo F., Chomienne C. The t(15;17) translocation alters a nuclear body in a RA-reversible fashion. EMBO J. 1994;13:1073–1083. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel M.-T., Koken M., Romagné O., Barbey S., Bazarbachi A., Stadler M., Guillemin M.-C., Degos L., Chomienne C., de Thé H. PML protein expression in hematopoietic and acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 1993;82:1858–1867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck J.A., Maul G.G., Miller W.H., Chen J.D., Kakizuka A., Evans R.M. A novel macromolecular structure is a target of the promyelocyte-retinoic acid receptor oncoprotein. Cell. 1994;76:333–343. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis K., Rambaud S., Lavau C., Jansen J., Carvalho T., Carmo-Fonseca M., Lamond A., Dejean A. Retinoic acid regulates aberrant nuclear localization of PML/RARα in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cell. 1994;76:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matera A.G. Nuclear bodiesmultifaceted subdomains of the interchromatin space. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:302–309. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S., Muller S., Ronchetti S., Freemont P.S., Dejean A., Pandolfi P.P. Role of SUMO-1-modified PML in nuclear body formation. Blood. 2000;95:2748–2752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishov A.M., Sotnikov A.G., Negorev D., Vladimirova O.V., Neff N., Kamitani T., Yeh E., Strauss J., Maul G. PML is critical for ND10 formation and recruits the PML-interacting protein Daxx to this nuclear structure when modified by SUMO-1. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:221–234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rego E., Wang Z.G., Peruzzi D., He L.Z., Cordon-Cardo C., Pandolfi P.P. Role of promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) in tumor supression. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:1–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan R., Delphin C., Guan T., Gerace L., Melchior F. A small ubiquitin-related polypeptide involved in targeting RanGAP1 to nuclear pore complex protein RanBP2. Cell. 1997;88:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81862-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desterro J.M.P., Rodriguez M.S., Hay R.T. SUMO-1 modification of IκBα inhibits NF-κB activation. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitani T., Kito K., Nguyen H.P., Wada H., Fukuda-Kamitani T., Yeh E.T.H. Identification of three major sentrinization sites in PML. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;41:26675–26682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprez E., Saurin A.J., Desterro J.M., Lallemand-Breitenbach V., Howe K., Boddy M.N., Solomon E., de Thé H., Hay R.T., Freemont P.S. SUMO-1 modification of the acute promyelocytic leukaemia protein PMLimplications for nuclear localization. J. Cell. Sci. 1999;112:381–393. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S., Matunis M.J., Dejean A. Conjugation with the ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO-1 regulates the partitioning of PML within the nucleus. EMBO J. 1998;17:61–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii S., Egan D.A., Evans R.A., Reed J.C. Human Daxx regulates Fas-induced apoptosis from nuclear PML oncogenic domains (PODs) EMBO J. 1999;18:6037–6049. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehembre F., Muller S., Pandolfi P.P., Dejean A. Regulation of Pax3 transcriptional activity by SUMO-modified PML. Oncogene. 2001;20:1–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Koken M.H.M., Quignon F., Chelbi-Alix M.K., Degos L., Wang Z.Y., Chen Z., de The H. Arsenic-induced PML targeting onto nuclear bodiesimplications for the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:3978–3983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitani T., Nguyen H.P., Kito K., Fukuda-Kamitani T., Yeh E.T.H. Covalent modification of PML by the sentrin family of ubiquitin-like proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3117–3120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler M., Chelbi-Alix M.K., Koken M.H.M., Venturini L., Lee C., Saïb A., Quignon F., Pelicano L., Guillemin M.-C., Schindler C., de Thé H. Transcriptional induction of the PML growth suppressor gene by interferons is mediated through an ISRE and a GAS element. Oncogene. 1995;11:2565–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B.R., Eleftheriou A. A comparison of the activity, sequence specificity, and CRM1-dependence of different nuclear export signals. Exp. Cell. Res. 2000;256:213–224. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao W., Fanelli M., Ferrara F.F., Riccioni R., Rosenauer A., Davison K., Lamph W.W., Waxman S., Pelicci P.G., Lo Coco F. Arsenic trioxide as an inducer of apoptosis and loss of PML/RARα protein in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998;90:124–133. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Gianni M., Kopf E., Honore N., Chelbi-Alix M., Koken M., Quignon F., Rochette-Egly C., de The H. Retinoic acid induces proteasome-dependent degradation of retinoic acid receptor α (RARα) and oncogenic RARα fusion proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:14807–14812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuurman N., de Graaf A., Floore A., Josso A., Humbel B., de Jong L., van Driel R. A monoclonal antibody recognizing nuclear matrix-associated nuclear bodies. J. Cell. Sci. 1992;101:773–784. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.4.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett R.D., Lomonte P., Sternsdorf T., van Driel R., Orr A. Cell cycle regulation of PML modification and ND10 composition. J. Cell. Sci. 1999;112:4581–4588. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.24.4581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nervi C., Ferrara F.F., Fanelli M., Rippo M.R., Tomassini B., Ferrucci P.F., Ruthardt M., Gelmetti V., Gambacorti-Passerini C., Diverio D. Caspases mediate retinoic acid-induced degradation of the acute promyelocytic leukemia PML/RARα fusion protein. Blood. 1998;92:2244–2251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam Y.W., Ammerlaan W., Kroese F., Opstelten D. Cell type- and differentiation stage-dependent expression of PML domains in rat, detected by monoclonal antibody HIS55. Exp. Cell Res. 1995;221:344–356. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMorte V.J., Dyck J.A., Ochs R.L., Evans R.M. Localization of nascent RNA and CREB binding protein with the PML-containing nuclear body. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:4991–4996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vom Baur E., Zechel C., Heery D., Heine M.J.S., Garnier J.M., Vivat V., Le Douarin B., Gronemeyer H., Chambon P., Losson R. Differential ligand-dependent interactions between the AF-2 activating domain of nuclear receptors and the putative transcriptional intermediary factors mSUG1 and TIF1. EMBO J. 1996;15:110–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami Y., Kawasaki H., Minami M., Tanahashi N., Tanaka K., Yahara I. A critical role for the proteasome activator PA28 in the HSP90-dependent protein refolding. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9055–9061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.9055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joazeiro C., Weissman A. RING finger proteinsmediators of ubiquitin ligase activity. Cell. 2000;102:549–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabunmi R., Wigley C., Thomas P., De Martino G. Interferonγ regulates accumulation of the proteasome activator PA28 and immunoproteasome at nuclear PML bodies. J. Cell. Sci. 2001;114:24–36. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flenghi L., Fagioli M., Tomassoni L., Pileri S., Gambacorta M., Pacini R., Grignani F., Casini T., Ferrucci P.F., Martelli M.F. Characterization of a new monoclonal antibody (PG-M3) directed against the aminoterminal portion of the PML gene productimmunocytochemical evidence for high expression of PML proteins on activated macrophages, endothelial cells, and epithelia. Blood. 1995;85:1871–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton L.C., Schubert U., Bacik I., Princiotta M.F., Wearsch P.A., Gibbs J., Day P., Realini C., Rechsteiner M., Bennink J., Yewdell J. Intracellular localization of proteasomal degradation of a viral antigen. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:113–124. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P., Guo Y., Niu Q., Levy D.E., Dyck J.A., Lu S., Sheiman L.A., Liu Y. Proto-oncogene PML controls genes devoted to MHC class I antigen presentation. Nature. 1998;396:373–376. doi: 10.1038/24628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman S.R., Perez M., Kung A.L., Joseph M., Mansur C., Xiao Z.X., Kumar S., Howley P.M., Livingston D.M. p300/MDM2 complexes participate in MDM2-mediated p53 degradation. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:405–415. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelbi-Alix M.K., de The H. Herpes virus induced proteasome-dependent degradation of the nuclear bodies-associated PML and Sp100 proteins. Oncogene. 1999;18:935–941. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett R.D., Freemont P., Saitoh H., Dasso M., Orr A., Kathoria M., Parkinson J. The disruption of ND10 during herpes simplex virus infection correlates with the VmW110- and proteasome-dependent loss of several PML isoforms. J. Virol. 1998;72:6581–6591. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6581-6591.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S., Dejean A. Viral immediate-early proteins abrogate the modification by SUMO-1 of PML and Sp100 proteins, correlating with nuclear body disruption. J. Virol. 1999;73:5137–5143. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.5137-5143.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]