Abstract

We have studied the effect of patch excision on the gating kinetics of muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors transiently expressed in HEK 293 cells. The experiments were performed on embryonic and adult wild-type, and several mutated, receptors using acetylcholine, carbamylcholine and tetramethylammonium as agonists.

We show that patch excision of cell-attached patches into the inside-out configuration led to a reduction of mean open duration in receptors containing a γ-subunit (embryonic) but not an ɛ-subunit (adult receptors).

Kinetic analysis of an embryonic receptor containing a mutated residue, αY93F, showed that the reduction in the mean open duration upon patch excision was mainly caused by an increase in the channel closing rate constant. This was confirmed by experiments on embryonic wild-type receptors using carbamylcholine as an agonist with low efficacy.

By expressing receptors containing chimeric γ-ɛ subunits we found that segments of the γ-subunit corresponding to a region within the M3-M4 linker (the amphipathic helix, HA) and the M4 transmembrane domain were required for the reduction in channel open duration after excision.

The results indicate that particular residues in both M4 and HA are required to allow the change in open time after excision. This finding suggests that there is an interaction between these two regions in determining the modulation of gating kinetics.

The nicotinic receptor found at the skeletal muscle neuromuscular junction is among the best studied of the ligand-gated ion channels. The receptor is a pentamer. It occurs in two forms: embryonic receptors are composed of two α-subunits, and one each of β-, δ- and γ-subunits; in the adult receptor, the γ-subunit is replaced by a homologous ɛ-subunit. The activation kinetics of the two types of receptors have been extensively studied (Sine et al. 1990; Auerbach, 1993; Aylwin & White, 1994; Zhang et al. 1995; Akk & Auerbach, 1996; Maconochie & Steinbach, 1998), and a major difference between the two has been shown to occur in the channel closing rate. This rate is about 4-fold larger in the adult form.

The rates for steps in the activation of both types of muscle nicotinic receptors depend on the structure of the subunits, and can be altered by mutations in several regions (Sine et al. 1995; Wang et al. 1997; Akk et al. 1999). However, activation steps do not seem to be affected by post-translational manipulations such as phosphorylation. One exception is the report that the mean open time for embryonic receptors changes after excision of the patch (Trautmann & Siegelbaum, 1983; Covarrubias & Steinbach, 1990). The mean apparent open time is reduced by 2- to 3-fold following excision, over a period of about 10 min (Covarrubias & Steinbach, 1990). It was concluded that an increase in the channel closing rate was the major reason for the change, although possible changes in the channel opening rate or acetylcholine dissociation rate were not ruled out as less important contributors (Covarrubias & Steinbach, 1990).

We are interested in this observation for two reasons. The first is that understanding the basis for the change may provide some insight into the mechanisms by which receptor activation is controlled. The second is that the influence of patch configuration on activation rate constants may explain some of the variability in kinetic estimates which have been made in various studies. For example, according to Aylwin & White (1994), the channel closing rate constant of mouse embryonic wild-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) is 886 s−1 while Zhang et al. (1995) found it to be almost 4-fold lower (240 s−1). This difference is likely to arise from the different patch-clamp configurations used –Aylwin & White (1994) worked on outside-out patches, Zhang et al. (1995) used cell-attached patch clamp.

In the present work, we have demonstrated that the influence of patch excision persists when embryonic receptors are expressed in non-muscle-derived cells. We have used both mutated subunits and low efficacy agonists to directly examine the kinetic alterations which result in the reduction of burst duration. Both approaches allow the separation of any kinetic effects into affinity- and efficacy-based components. This is so because the channel opening is slowed when the receptors are activated by carbamylcholine or tetramethylammonium (Akk & Auerbach 1996, 1999). Similarly, a mutant receptor used in the present study has a channel opening rate constant which is ∼50-fold lower compared to the wild-type receptor, making a direct determination of the channel opening rate constant technically feasible (αY93F, Auerbach et al. 1996). We used both approaches to eliminate the possibility that wild-type receptors activated by carbamylcholine (CCh) or tetramethylammonium (TMA), or mutant receptors activated by ACh, behave qualitatively differently from ACh-activated wild-type receptors. Both approaches confirmed that an increase in the channel closing rate is the major underlying cause for excision-elicited shortening of burst durations.

We have extended the observations by demonstrating that there is no apparent effect of excision on adult receptors. Finally, by use of chimeric subunits formed from γ- and ɛ-subunits, we have established that regions near the carboxy terminus of the subunits are required for the effect of excision. Specific residues in both the amphipathic helix (HA) region of the major cytoplasmic loop of the subunit and the M4 membrane spanning region must be present for excision to have an effect. It is interesting that these regions are the same as those shown earlier (Bouzat et al. 1994) to underlie the characteristic difference in burst durations seen for adult and embryonic receptors activated by acetylcholine.

METHODS

Expression systems and electrophysiology

Mouse muscle-type nAChR subunit cDNAs (α, β, γ, δ, ɛ) originally came from the laboratories of the late Dr John Merlie and Dr Norman Davidson, and were subcloned into a CMV promoter-based expression vector pcDNAIII (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA) or pRBG4 (Sine, 1993). The α-subunit differed from the sequence in the GenBank database (accession X03986) by having an alanine rather than valine at position 433 (Salamone et al. 1999). The αY93F and all chimeric mutant clones were generously provided by Dr Steven Sine. The descriptions of chimeric subunits are given in Results. The exact positions of chimeras are as follows: χ9: γ424ɛ454γ, i.e. a γ-subunit with a region between residues 424 and 454 replaced by a homologous region from the ɛ-subunit; χ19: ɛ397γ427ɛ; χ32: an ɛ-subunit with two point mutations, W439L, A441M; χGINE: ɛ397γ427ɛ plus two point mutations, W439L, A441M; γWA: a γ-subunit with two point mutations, L457W, M459A. The nAChRs were expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells using transient transfection based on calcium phosphate precipitation (Ausubel et al. 1992). A total of 3.5 μg of DNA per 35 mm culture dish in the ratio 2:1:1:1 (α:β:δ:γ/ɛ) was used. The DNA was added to the cells for 12–24 h, after which the medium was changed. Electrophysiological recordings were performed 24–48 h later.

Electrophysiology was performed using the patch-clamp technique in the cell-attached and inside-out configurations (Hamill et al. 1981). The bath and pipette solutions contained (mm): 142 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.7 MgCl2, 5.4 NaCl, 10 Hepes, pH 7.4. In addition, the pipette solution contained the indicated concentration of ACh, CCh or TMA. All experiments were performed at 22–24°C. In most experiments, the membrane potential was held at values between −80 and −60 mV. For each data point in Table 2, we recorded channel activity at four to ten different membrane potentials (usually between −100 and −20 mV). In the case of inside-out patches, we waited at least 10 min after patch excision to reach equilibrium before starting the recordings (Covarrubias & Steinbach, 1990).

Table 2. The effect of patch excision on the channel open duration and voltage sensitivity.

| Cell attached | Inside out | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor | Agonist | τo (ms) | f | n | τo (ms) | f | n | Ratio τo i/o:c/a |

| αβγδ | ACh | 4.4 | 0.20 | 1 | 2.11 | 0.28 | 1 | 0.48 |

| αβγδ | CCh | 1.32 ± 0.37 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 5 | 0.67 ± 0.17 | 0.37 ± 0.08 | 4 | 0.51* |

| αY93Fβγδ | ACh | 1.04 ± 0.06 | 0.27 ± 0.16 | 2 | 0.52 ± 0.09 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 3 | 0.50* |

| αβδε | ACh | 0.39 ± 0.09 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 2 | 0.52 ± 0.12 | 0.23 ± 0.11 | 3 | 1.33 |

| αβδε | CCh | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 2 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 2 | 1.0 |

| αβδε | TMA | 0.25 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 1 | 1.04 |

| αY93Fβδε | ACh | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 3 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.006 | 3 | 0.80 |

| αY93Fβδχ9 | ACh | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 2 | 0.73 ± 0.08 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 2 | 1.40* |

| αβδχ19 | TMA | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.006 | 3 | 0.26 ± 0.0 | 0.31 ± 0.007 | 2 | 0.81 |

| αβδχ32 | TMA | 0.27 ± 0.11 | 0.28 ± 0.07 | 3 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.006 | 3 | 1.07 |

| αβδχGINE | TMA | 0.57 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 3 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.05 | 3 | 0.51* |

| αβδγWA | TMA | 1.36 ± 0.07 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 3 | 1.43 ± 0.05 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 3 | 1.05 |

The channel open duration at 0 mV membrane potential (τo) and voltage sensitivity (f) were calculated using eqn (1) (see Methods). Values are shown as means ±s.d.from n experiments. The structures of the constructs used are given in Methods and Fig. 5. The degree of voltage sensitivity (f) can be converted to mV per e-fold change by dividing 25 mV by f. Asterisks in column ‘ratio τo’ denote statistically significant (P < 0.05) changes.

Kinetic analysis

Most experiments were performed using low, non-desensitizing concentrations of agonists. At such concentrations (for wild-type receptors, [ACh]≤ 10 μm, [CCh]≤ 100 μm, [TMA]≤ 200 μm), receptor activity takes place as isolated bursts or openings without condensing into clusters (Sakmann et al. 1980). The advantage of using low concentrations of agonists is the lack of agonist-caused channel block which may result in reduced apparent single-channel amplitude and increased apparent open times. Single-channel currents were amplified with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments), digitized at 50 kHz, and saved on a PC hard disk using a Digidata 1200 series interface (Axon Instruments). For event detection, the data were low-pass filtered at 2–5 kHz and idealized using the segmented-k-means algorithm (program SKM, Qin et al. 1996, 1997). Mean open and closed interval durations were estimated from the histograms of interval dwell times. For Table 2, the data recorded at different voltages were fitted using the following equation:

| (1) |

where τ is the mean open duration at membrane voltage V (in mV), τ0 is the mean open duration at V = 0 mV, f is the fraction of the electric field that would be traversed by a single positive charge to produce the observed voltage dependence, and kT = 25 mV. This equation describes the increase in the mean open duration as the electrical potential becomes more negative. Mean open times were estimated from a single exponential fit to the data set, with a correction for missed brief events (Qin et al. 1997). However, it should be noted that in a few cases (e.g. embryonic wild-type receptors at 100 μm ACh), a better fit was obtained using a sum of two exponentials. Due to the scarcity of such occasions, we used single exponential fits for all data sets.

Concentration-response relationship for receptors containing the αY93F subunit

Receptors containing the αY93F subunit were used to characterize channel activation by ACh at multiple concentrations, in both the cell-attached and excised patch configuration. Two kinds of concentration-response curves were constructed. First, the probability of being open within a cluster (Po) was determined as a function of ACh concentration. This curve is similar to a whole-cell concentration-response curve, freed from the effects of desensitization (Sine & Steinbach, 1987; Colquhoun & Ogden, 1988). At the single-channel level, desensitization of nicotinic receptors is manifest as the termination of the cluster. We only analysed intracluster events, and thus desensitization did not influence the Po estimate.

For the second concentration-response profile, the slowest component of the intracluster closed interval duration distribution was measured as a function of ACh concentration. The inverse of this duration was defined as the effective opening rate, β′. As the agonist concentration increases, the closed intervals within clusters become briefer, and β′ increases. At very high agonist concentrations Model 1 (see below) reduces to: A2C ⇌ A2O, and the effective opening rate will approach the intrinsic opening rate constant (β) of the receptor.

(Model 1).

Both Po and β′vs.[agonist] curves were fitted by an empirical equation (the Hill equation):

| (2) |

where the response (Po or β′) is at agonist concentration A, EC50 is the concentration that produces a half-maximal response, and n is the Hill coefficient. It was necessary to use a high concentration of ACh to observe saturation of the effects (highest concentration 8 mm). At this concentration, ACh is known to produce open channel block of receptors containing αY93F (Auerbach & Akk, 1998). For our measurements, block would be manifest as a prolongation of apparent open times and an increase in apparent Po. The prolongation of open times appears relatively small (see Results), and we have made no correction for block in the analysis.

Finally, a full kinetic analysis was performed on results obtained for receptors containing the αY93F subunit. The analysis was restricted to clusters of channel openings that each reflects the activity of a single nAChR (Sakmann et al. 1980). Clusters were defined as series of openings separated by closed intervals shorter than some critical duration (τcrit). The value of τcrit depended on the concentration of agonist, but was always at least five times longer than the slowest (and main) component of closed intervals within clusters that scaled with the agonist concentration. For example, τcrit was 200 ms in the presence of 500 μm ACh, and 100 ms in the presence of 8 mm ACh (for both adult and embryonic receptors). The definition of clusters was usually not sensitive to the value of τcrit because this component of closures and the component associated with desensitization typically were well separated. The data used for the analysis were obtained using ACh concentrations of 500 μm or 1 mm, to reduce the contribution of block to the data. Accordingly, a blocking step was not included in the kinetic scheme used in the analysis and no corrections were applied to the parameter estimates.

The following kinetic scheme was used to describe the interval durations in the αY93F receptor. A closed, unoccupied receptor (C) binds two agonist molecules (A) and eventually becomes a doubly liganded, open receptor (A2O) (Katz & Thesleff, 1957): where k+ 1 and k+ 2 are the agonist association rate constants, k−1 and k−2 are the agonist dissociation rate constants, β is the channel opening rate constant, and α is the channel closing rate constant. If the agonist-binding properties of the two transmitter docking sites are equivalent, then k+ 1 = 2k+ 2, k−2 = 2k−1 and the microscopic dissociation equilibrium constant of each site (Kd) is k−1/k+ 2. The gating equilibrium constant (Θ) is β/α. The rate constants for agonist association, agonist dissociation and channel closing were determined from the analysis of idealized intracluster interval durations using Q-matrix methods (program MIL). A maximum-likelihood method was employed that incorporated a correction for missed events (Qin et al. 1996). The rate constants were optimized using interval durations combined from files obtained at ACh concentrations of 500 μm and 1 mm. The minimal duration (dead time) was set to 45 μs. Standard deviations for the rate constants were estimated from the curvature of the likelihood surface at its maximum using the approximation of parabolic shape (Qin et al. 1996). The channel opening rate constant was constrained to the value obtained from fitting the β′ curve. This was done in order to reduce the number of free parameters.

Drugs

Acetylcholine chloride, carbamylcholine chloride and tetramethylammonium chloride were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company.

RESULTS

Wild-type embryonic receptors activated by ACh and CCh

We have examined the effect of patch excision on the resolved open duration of muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors transiently expressed in HEK 293 cells. Figures 1 and 2 show the effect of excision on ACh-activated wild-type receptors. When the embryonic receptor was activated by 5 μm ACh (Fig. 1A), the mean apparent open duration decreased 2-fold, from 6 to 3 ms after excision of the patch. At such low agonist concentration, openings take place in bursts separated from each other by closed intervals which depend on both the kinetic properties of the receptor and the number of channels in the patch. Bursts contain an average of 2–3 openings, the number dependent on the ratio of the channel opening rate to the agonist dissociation rate (the ‘re-opening ratio’, β/k−2 in Model 1, see Methods). The openings are separated by gaps shorter than the recording resolution, and therefore the mean apparent open time measured is the lifetime of a burst rather than of an opening. Since the lifetime of a burst is dependent on both the channel closing rate constant (α) and the β/k−2 ratio, the reduction in the open duration can result from changes in any of the three rate constants.

Figure 1. The effect of patch excision on single-channel activity from embryonic wild-type receptors.

A, single-channel openings elicited by 5 μm ACh in cell-attached and inside-out configurations, and their respective open interval duration histograms (different patches; 1899 and 1459, events, respectively). B, single-channel clusters elicited by 100 μm ACh in cell-attached and inside-out configurations, and their respective closed and open interval duration histograms (different patches; 1730 and 3586 events, respectively). The membrane potential was −70 mV; inward current is downward. Open time histograms were fitted with a single exponential, and the time constants are given in the figure. The closed time histograms were fitted with the sum of two exponentials, and the time constants are given in the figure.

Figure 2. The effect of patch excision on single-channel activity from adult wild-type receptors.

A, single-channel openings elicited by 5 μm ACh in cell-attached and inside-out configurations, and their respective open interval duration histograms (different patches; 694 and 440 events, respectively). B, single-channel openings elicited by 50 μm CCh in cell-attached and inside-out configurations, and their respective open interval duration histograms (different patches; 703 and 664 events, respectively). The membrane potential was −70 mV; inward current is downward. The histograms were fitted with a single exponential, and the time constants are given in the figure.

A similar effect of excision was seen when embryonic wild-type receptors were activated by a higher concentration of ACh (100 μm, Fig. 1B; see also Covarrubias & Steinbach, 1990). The mean apparent open duration was reduced >2-fold. At such high agonist concentrations channel openings take place in clusters. The duration and relative abundance of the components in the closed interval distributions within a cluster depend on several rates, including those for agonist dissociation and subsequent re-binding and channel re-opening. Comparison of closed interval durations gives a rough estimate of the effects that patch excision has on agonist association and dissociation. Our results show little difference in the closed time histograms suggesting that the receptor affinity for ACh is relatively unaffected by the patch configuration. The results obtained using ACh as an agonist confirm the observations of Covarrubias & Steinbach (1990), and demonstrate that similar effects are seen when embryonic receptors are transiently expressed in non-muscle cells.

To extend the analysis, we examined the effect of excision on receptors activated by the low efficacy agonists carbamylcholine (CCh) or tetramethylammonium (TMA). When a low efficacy agonist is used, the apparent open time actually measures the true open time, rather than the burst duration. This is so because the channel re-opening ratio, β/k−2, is greatly reduced compared to that for ACh. Accordingly, once the channel closes, the ligand dissociates and only a single open dwell results (Zhang et al. 1995). We found that there was a very similar effect of excision on the mean open times for embryonic receptors activated by CCh (Fig. 6, lane 2) as for activation by ACh (Fig. 6, lane 1; see also Table 2). Accordingly, patch excision mainly affects the channel closing rate constant.

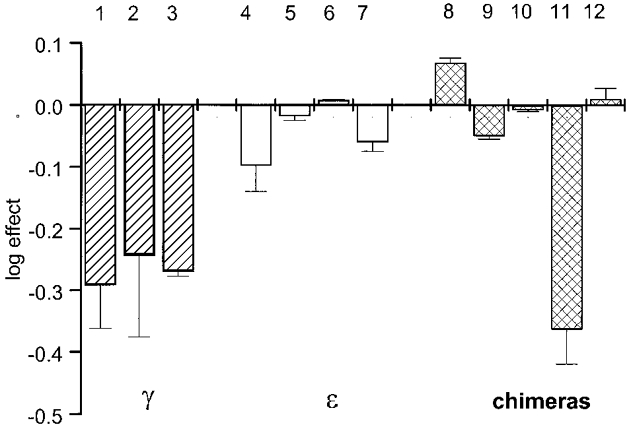

Figure 6. Summary of the effects of patch excision on the open duration of single-channel openings measured at membrane potentials between −80 and −60 mV.

The change in the apparent open duration (shown as log effect) is calculated as the mean effect from 2–6 experiments (±s.d.). The columns show data from the following constructs and agonists: embryonic receptors (1–3): 1, αβγδ (ACh); 2, αβγδ (CCh); 3, αY93Fβγδ (ACh); adult receptors (4–7): 4, αβδɛ (ACh); 5, αβδɛ (CCh); 6, αβδɛ (TMA); 7, αY93Fβδɛ (ACh); chimeric receptors (8–12): 8, αY93Fβδχ9 (ACh); 9, αβδχ19 (TMA); 10, αβδχ32 (TMA); 11, αβδχGINE (TMA); 12, αβδγWA (TMA). For all agonists, non-desensitizing concentrations were used (see Methods). The effects of patch excision were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in lanes 1, 2, 3 and 11.

Wild-type adult receptors activated by ACh, CCh and TMA

Surprisingly, when similar experiments were performed on the adult wild-type receptor, patch excision did not result in changes in channel open duration. Figure 2A shows channel activity elicited by 5 μm ACh in cell-attached and inside-out configurations. The apparent open durations are shorter than in embryonic receptors due to a severalfold faster channel closing rate constant. The results show little effect of excision (Fig. 6 and Table 2). However, as for the embryonic receptor, the burst duration is actually measured when ACh is used as agonist, each a series of two to three openings (Akk & Auerbach, 1996).

We used two low efficacy agonists to activate adult receptors, CCh and TMA. In each case, bursts contain only a single opening (due to a low β/k−2 ratio), and so the apparent open time measures the true duration of single openings (Akk & Auerbach, 1996; Akk & Auerbach, 1999). In each case, the results showed no effect of excision on the open times for adult receptors (Fig. 6 and Table 2).

Analysis of the receptor containing the mutated subunit, αY93F

We further investigated the effect of patch excision on the kinetic properties of nicotinic receptors, utilizing a receptor containing a mutated α-subunit in which a conserved tyrosine residue at position 93 is replaced by phenylalanine (αY93F). This residue has been shown to be involved in agonist binding, and mutations of the residue affect the apparent affinity as judged from binding studies and whole-cell concentration-response curves which are shifted towards higher agonist concentrations (Sine et al. 1994; Kearney et al. 1996). In addition to changes in agonist affinity, the mutation slows channel opening ∼60-fold in receptors containing an ɛ-subunit (Auerbach et al. 1996). Use of this mutant receptor permitted us to study channel kinetics in detail as the opening rate constant can be obtained directly from the saturation of the effective opening rate for both cell-attached and excised patches. This makes the analysis more direct compared to using a wild-type receptor where the opening rate constant is too fast to be measured from single-channel currents and is usually determined by other methods (Maconochie & Steinbach, 1998).

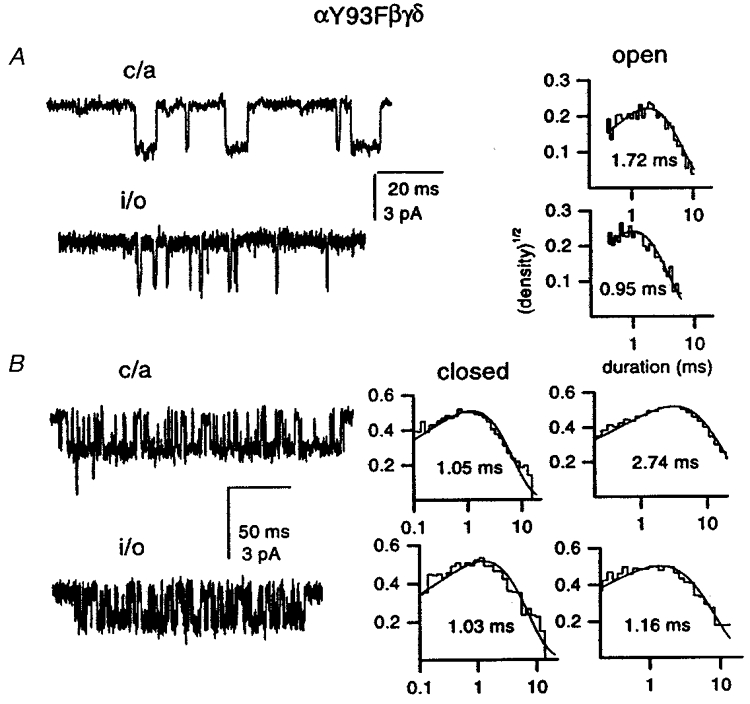

Figure 3 shows single-channel currents from αY93Fβγδ receptors elicited by 50 μm and 8 mm ACh in cell-attached and inside-out configurations. At 50 μm ACh, patch excision caused an almost 2-fold decrease in the mean open duration. The changes in closed interval durations could not be studied because the openings did not take place in clusters at this concentration of ACh, and the mean closed interval duration within a patch is dependent on the number of active receptors in the patch. However, in the presence of 8 mm ACh, channel activity occurred in clusters. The open durations were somewhat prolonged compared to those at 50 μm ACh. This is likely to be the result of channel block by ACh (see Methods). However, patch excision caused a reduction in the open time as shown above for lower agonist concentrations. Comparison of closed interval duration histograms shows that the closed times are similar in cell-attached and inside-out configurations (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. The effect of patch excision on single-channel activity from Y93Fβγδ receptors.

A, single-channel openings elicited by 50 μm ACh in cell-attached and inside-out configurations, and their respective open interval duration histograms (different patches; 422 and 389 events, respectively). B, single-channel clusters elicited by 8 mm ACh in cell-attached and inside-out configurations, and their respective closed and open interval duration histograms (different patches; 10606 and 3920 events, respectively). The membrane potential was −70 mV; inward current is downward. The closed and open time histograms were fitted with a single exponential, and the time constants are given in the figure.

Figure 4A shows the effective opening and closing rates, and Po curves for the αY93Fβγδ receptor in cell-attached and inside-out configurations. The data show that the channel opening rate constant was not affected by patch excision. The channel closing rate constant was approximately 2-fold faster in the inside-out than in the cell-attached configuration leading to a reduction in the maximal Po.

Figure 4. Concentration-response parameters for the αY93Fβγδ and αY93Fβδɛ mutant receptors.

A, effective opening rate, effective closing rate and Po for αY93Fβγδ receptors as a function of [ACh]. Open symbols are for cell-attached, filled symbols for inside-out patches. Each symbol shows data from one patch. Continuous lines are from fits to the Hill equation. For cell-attached patches: β = 1016 s−1, α’ = 401 s−1, Po,max = 0.76, EC50 = 631 μm, n = 1.3. For inside-out patches: β = 1078 s−1, α’ = 822 s−1, Po,max = 0.55, EC50 = 701 μm, n = 2.2. B, effective opening, effective closing rate and Po of αY93Fβδɛ as a function of [ACh]. For cell-attached patches: β = 1220 s−1, α’ = 1708 s−1, Po,max = 0.38, EC50 = 1145 μm, n = 1.8. For inside-out patches: β = 1097 s−1, α’ = 1866 s−1, Po,max = 0.35, EC50 = 1424 μm, n = 1.6.

We further examined the effect of patch excision on channel kinetics by estimating the channel activation rate constants in cell-attached and inside-out configurations. We used Model 1 in which the channel opening rate constant was constrained to a value obtained from the saturation of the β′ curves (1016 or 1078 s−1, respectively). We imposed an additional constraint, for the agonist binding sites to be of identical affinity. Relaxation of this constraint caused only a marginal improvement of the fit (log-likelihood improved by 5 units with the addition of 2 free parameters), suggesting that the affinities are too similar to be reliably separated. The results are summarized in Table 1, and show that patch excision has a major effect on channel gating mediated exclusively by an increase in the channel closing rate constant. In addition, patch excision may cause a slight reduction in affinity with effects on both agonist association and dissociation rate constants.

Table 1. The effect of patch excision on the activation by ACh of receptors containing the αY93F subunit.

| αY93Fβγδ | αY93Fβδε | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c/a | i/o | c/a | i/o | |

| A. Kinetic analysis | ||||

| k+ (μm−1 s−1) | 14.1 ± 4.4 | 19.5 ± 11.6 | 8.2 ± 1.2 | 7.6 ± 1.5 |

| k− (s−1) | 7061 ± 2260 | 12 184 ± 7413 | 5153 ± 763 | 6560 ± 1357 |

| Kd (μm) | 501 ± 223 | 625 ± 532 | 628 ± 93 | 863 ± 247 |

| β (s−1) | (1016 ± 99) | (1078 ± 144) | (1220 ± 269) | (1097 ± 258) |

| α (s−1) | 436 ± 11 | 777 ± 23 | 2919 ± 65 | 2434 ± 49 |

| β/α | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 0.45 ± 0.11 |

| B. Concentration response | ||||

| Po,max | 0.76 ± 0.12 | 0.55 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.01 |

| Po EC50 (μm) | 631 ± 182 | 701 ± 49 | 1145 ± 170 | 1424 ± 66 |

| β (s−1) | 1016 ± 99 | 1078 ± 129 | 1220 ± 269 | 1097 ± 258 |

| α (s−1) | 401 ± 54 | 822 ± 84 | 1708 ± 353 | 1866 ± 252 |

A. Parameter estimates from the analysis of singlechannel activity within clusters. Rate constants were calculated using the programs SKM and MIL as described in Methods. Data were filtered at 4 kHz; dead time was set at 45 μs. For αY93βγδ receptors the data for cellattached patches consisted of results from 2 patches (1 with 0.5 mm ACh, 1 with 1 mm ACh, 3212 events total) while the data for insideout patches were obtained from two different patches (1 with 0.5 mm ACh, 1 with 1 mm ACh, 2382 events total). For αY93βδε receptors the data for cellattached patches consisted of results from 1 patch (0.5 mm ACh, 3924 events) while the data for insideout patches were obtained from two different patches (1 with 0.5 mm ACh, 1 with 1 mm ACh, 5288 events total). Both data sets were analysed assuming identical agonist binding sites. The channel opening rate constant (β) was constrained to the value obtained from the saturation of the effective opening rate curve (Fig. 4). Values are given as best fit ±s.d. B. Parameter estimates from the concentration–response curves (see Fig. 4). Values are given as best fit ±s.d. Abbreviations: c/a, cellattached; i/o, insideout.

We also studied the activation of αY93Fβδɛ receptors. Figure 4B shows the effective opening and closing rates, and Po curves for the adult mutant receptor in cell-attached and inside-out patches. Similar to the adult wild-type receptors, patch excision had little effect on channel kinetics. Thus, the activation of embryonic but not adult-type mutant receptors is affected by patch configuration. This is supported by a detailed activation rate constant analysis on the αY93Fβδɛ receptor currents. Table 1 shows the agonist association and dissociation, and channel opening and closing rate constants obtained from the analysis. The results show that neither α nor β is significantly affected by patch excision, although there may be a slight reduction in affinity.

Localization of the critical region

By using wild-type and mutant nicotinic receptors, we have shown that an excision-dependent increase in the channel closing rate is evident in embryonic (γ-subunit containing) but not in adult (ɛ-subunit containing) receptors. We decided to investigate the structural requirements for this phenomenon. We reasoned that the critical structures were likely to be in the major cytoplasmic loop region of the subunit (between the membrane spanning regions M3 and M4), since it seemed possible that the effect of excision might reflect loss of an interaction with a cytoplasmic component. Previous work by others (Bouzat et al. 1994) had found that a region at the C-terminal portion of the cytoplasmic loop (termed the amphipathic helix or HA region) is critically involved in determining the difference in burst durations elicited by ACh from embryonic and adult receptors. Accordingly, it seemed appropriate to determine whether this region was also of importance in the subunit-specific effect of excision which we were studying.

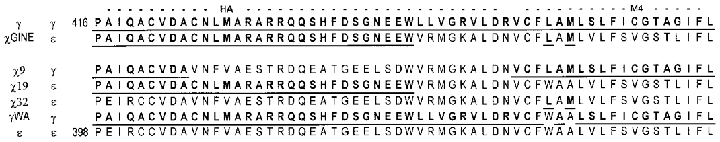

We used a set of five altered subunits, which were also studied by Bouzat et al. (1994). In all cases the residues affected were towards the carboxy terminus of the subunits, in the regions of the amphipathic helix (HA) and the M4 membrane spanning region. When possible, the constructs are identified with the notation of the original paper (χGINE and γWA were not named in the original report). The structures of the constructs are summarized in Fig. 5 (see also Methods). The observations are summarized in Fig. 6 and Table 2.

Figure 5. The aligned sequences of the constructs.

The portion of the sequences shown begins near the start of the HA region (indicated above the top line) and ends in the M4 region. The sequences starting at position 416 (γ-subunit, top line) or position 398 (ɛ-subunit, bottom line) are shown. Residues derived from the γ-subunit are shown in bold and underlined. The construct is identified in the left-most column. The second column gives the source of the sequence preceeding and following the portion shown (the backbone of the construct) – for example χ9 has residues from the γ-subunit before and after the region shown, whereas χGINE has residues from the ɛ-subunit.

We first examined the activation of a receptor containing χ9 co-expressed with αY93F, β- and δ-subunits. Chimeric subunit χ9 is based on the γ-subunit which has its HA domain replaced by the homologous region from the ɛ-subunit. Bouzat et al. (1994) found that this replacement produced a receptor having ɛ-like kinetics, that is, a brief burst duration. Our results show that patch excision does not result in a reduction of the mean open duration of the αY93Fβδχ9 receptor. In fact, the mean open time was slightly greater in excised than in cell-attached patches (cell-attached 1.11 ± 0.08 ms, n = 2; inside-out 1.30 ± 0.11 ms, n = 2). This suggests that at least some of the structural elements necessary for the excision-caused effect on channel closing rate constant are located in the HA region of the γ-subunit.

Next, we studied receptors containing chimeric subunits based on the ɛ-subunit in which different regions are replaced with equivalent domains from the γ-subunit. The χ19 is an ɛ-subunit that contains a γ-subunit HA domain, this is the inverse of the χ9 subunit. It has been shown previously that receptors containing a χ19-subunit have a burst duration intermediate between those of the adult and embryonic wild-type receptors (Bouzat et al. 1994). If the origin of the HA domain defines which receptors are affected by patch excision, then χ19-containing receptors should behave like embryonic receptors, and the closing rate constant should be increased in inside-out patches. However, we detected no such effect. Using TMA as a low efficacy agonist the mean open times were similar (cell-attached 0.75 ± 0.08 ms, n = 3; inside-out 0.67 ± 0.02 ms, n = 3). This suggests that the HA portion of the main cytoplasmic loop is not, in itself, sufficient to confer an excision-induced change in closing rate.

We then examined the effect of patch excision on an αβδχ32 receptor activated by TMA. The chimeric subunit χ32 is based on an ɛ-subunit and contains a double mutation in the M4 domain in which a tryptophan residue in position 439 is replaced by leucine and an alanine in position 441 is replaced by methionine (as in γ-subunit). Similar to χ19-containing channels, this receptor has a burst duration intermediate between adult and embryonic receptors (Bouzat et al. 1994). Our experiments showed that patch excision has no effect on mean open duration (mean open times for events elicited by TMA were: cell-attached 0.55 ± 0.11 ms, n = 3; inside-out 0.54 ± 0.11 ms, n = 3).

Next, we examined channel openings of the αβδχGINE receptor. The χGINE subunit is based on the ɛ-subunit, but contains two mutated regions: the HA domain is replaced by one from the γ-subunit (as in χ19), and the M4 domain contains two point mutations (as in χ32). This receptor has a long burst duration similar to the embryonic wild-type receptor (Bouzat et al. 1994). We found there was a clear decrease in the mean open duration following excision for receptors containing this chimera (mean open times for events elicited by TMA were: cell-attached 1.29 ± 0.12 ms, n = 3; inside-out 0.56 ± 0.07 ms, n = 3).

These results suggest that residues from the γ-subunit in both the HA and M4 regions are required for the effect of excision. However, a possible alternative interpretation is that the effect of excision is seen only when the closing rate is slower than some critical value. We distinguished these alternatives by examining the γWA construct which has two point mutations in its M4 region, L457W and M459A. These mutations are reciprocal to the ones found in χ32. Receptors containing the γWA subunit have long burst durations, as seen for the wild-type embryonic receptor (Bouzat et al. 1994). We found that the mean open duration of the mutant receptor, activated with TMA, was long and that there was no effect of excision (cell-attached 3.1 ± 0.46 ms, n = 3; inside-out 3.2 ± 0.5 ms, n = 3). Thus, the effect of excision clearly does not depend on the value for the channel closing rate. These results also confirm that specific residues in both the HA and M4 domains are required for the excision-elicited increase in the channel closing rate constant.

Voltage dependence of the mean open duration

It has been shown previously for nicotinic receptors that the mean open duration is dependent on the membrane potential (Magleby & Stevens, 1972; Neher & Sakmann, 1976; Colquhoun & Sakmann, 1985; Sine & Steinbach, 1986; Auerbach et al. 1996). Thus, changes in voltage sensitivity could produce a change in the mean open time or channel closing rate.

Therefore, we recorded channel activity at different voltages in cell-attached and inside-out configurations. Activity was recorded at four or more membrane potentials, and the mean open durations were fitted using eqn (1). An example of the analysis is shown in Fig. 7. Single-channel activity elicited by 5–50 μm CCh was recorded from embryonic and adult wild-type receptors. The data are plotted as the relationship between the mean open time and the amplitude of single-channel openings. The latter is related to membrane potential simply by Ohm >s law (assuming a linear I-V relationship). The data show that patch excision results in a reduction of open time durations recorded at the same membrane potential in the embryonic receptor but not in the adult-type receptor. Comparison of open durations at 0 membrane potential (τ0) shows the extent by which single-channel openings in inside-out patches are briefer than those in cell-attached patches. Table 2 presents values for τ0 and f (voltage sensitivity; see Methods) for the receptors we have studied, for data from cell-attached and inside-out patches. Even though there is some variability in the f values, we observed no systematic differences in voltage sensitivity in inside-out compared to cell-attached patches. Accordingly, the effect of excision does not result from a change in voltage dependence of the closing rate.

Figure 7. The relationship between mean open interval duration and amplitude of single-channel openings elicited by 5–50 μm CCh.

Circles: embryonic wild-type receptors (○, cell attached; •, inside-out); squares: adult wild-type receptors (□, cell attached, ▪, inside-out). The data were fitted using eqn (1). For embryonic receptors, τ0 = 1.8 ms and f = 0.33 for the cell-attached configuration, τ0 = 0.8 ms and f = 0.31 for the inside-out configuration. For adult receptors, τ0 = 0.19 ms and f = 0.29 for the cell-attached configuration, τ0 = 0.16 ms and f = 0.33 for the inside-out configuration.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that patch excision results in a reduction in the mean open time in embryonic but not in adult-type nicotinic receptors. This phenomenon is caused by an increase in the channel closing rate constant. The effect is mediated by two regions within the γ-subunit: the HA domain and two amino acid residues within the M4 region.

This is the first comparative study on cell-attached and inside-out recordings of nicotinic receptors utilizing advanced kinetic analysis. By using different agonists and mutant receptors we have shown that patch excision predominantly affects the channel closing rate constant. It is not trivial to account for a reduction in the mean burst duration observed in ACh-activated wild-type receptors. The burst duration at low ACh concentration is dependent on two kinetic processes (ligand binding and channel gating) which involve multiple kinetic parameters, including the agonist dissociation rate constant, and the channel opening and closing rate constants. Among these, the first two are very fast in ACh-activated receptors (β = 60000–80000 s−1, k−2 = 36000 s−1; Akk & Auerbach, 1996; Maconochie & Steinbach, 1998), making it close to impossible to evaluate them independently. We therefore used CCh and TMA, which have much lower channel opening rate constants (Akk & Auerbach, 1996; Akk & Auerbach, 1999). In addition, the agonist dissociation rate constant, k−2, is severalfold higher than the channel opening rate constant for CCh and TMA. Because of the low β/k−2 ratio, a burst is terminated after a single opening, and any changes in the observed open duration can be attributed to changes in the channel closing rate constant.

We have confirmed this by using a mutated receptor, αY93F. Here, the channel opening rate constant and ACh dissociation rate are low while the ratio of β/k−2 is <0.1. This ensures that the number of openings per burst is low even in the presence of ACh, and any changes in observed open durations can be accounted for by changes in the channel closing rate constant. Our results using wild-type receptors activated by CCh and TMA and mutated receptors activated by ACh demonstrate that patch excision affects the channel closing rate constant. We also found that the effect is not the result of altered voltage dependence, but results from a change in the intrinsic closing rate.

We performed a full kinetic analysis on αY93Fβγδ receptors. This analysis showed that in addition to a faster channel closing rate constant, patch excision may slightly affect agonist affinity. Small increases in both agonist association and dissociation rate constants led to a decrease in affinity for ACh (from 501 to 625 μm). This is consistent with the suggestion by Covarrubias & Steinbach (1990) that in addition to an increase in the channel closing rate constant, the β/k−2 ratio may be decreased in inside-out patches. The analysis of data from αY93Fβδɛ receptors showed no change in the channel closing rate, but, again, a slight reduction in affinity for ACh. The change in affinity is small, but is also apparent in the concentration-response curve for Po (Fig. 4). Accordingly, the major effect of excision is clearly on the channel closing rate, but there may also be a small reduction in the ratio β/k−2.

By using γ-ɛ chimeric subunits we have established that residues in two domains are required for the excision-caused decrease in the channel open duration. It was somewhat surprising to us that residues in both the main cytoplasmic loop (in the HA domain) and in a transmembrane region (M4) were required. However, separate changes in either region could remove the effect of excision from receptors containing constructs based on the γ-subunit, and changes in both regions were required to confer the effect on receptors containing constructs based on the ɛ-subunit. It is interesting to note that the effect does not appear to require residues outside these regions, as the ‘backbone’ of the chimeric receptor can be formed by either the γ- or the ɛ-subunit. The results agree with previous findings (see below) that there is an interaction between residues in the HA and M4 regions in determining channel kinetics. They also demonstrate that a post-translational effect on channel kinetics requires a particular interaction between these two regions.

It was previously shown that these two regions play a crucial role in determining the difference in the duration of ACh-elicited bursts between the embryonic and adult-type receptors (Bouzat et al. 1994). The burst durations of adult receptors can be reduced to that of embryonic receptors by two changes in the ɛ-subunit: swapping the HA domain and introducing two point mutations in the M4 segment. When applied separately, either change caused approximately half of the total effect. On the other hand, when changes were made in the γ-subunit, exchange of the HA region alone reduced the burst duration to that of adult receptors, while point mutations to the M4 region had no effect on the channel open duration. These findings clearly have some connection to our studies, and the results obtained with the HA region were a major reason for choosing these portions of the subunits for analysis of the effects of excision. However, there are some clear differences. In the case of the excision effect, residues in both the HA and M4 regions had to be derived from the γ-subunit. The presence of ɛ-derived residues in only one region prevented the effect of excision. In contrast, for the action on burst duration either changes in the two regions acted essentially independently (for changes introduced into the ɛ-subunit), or were required only in the HA region (for changes introduced into the γ-subunit). Overall, the data on the effect of excision suggest that there is an interaction between the HA and M4 regions which is required for excision to have an effect. The data on burst duration also suggest that there is an interaction between the two regions, but the consequences are less clear cut.

Our studies were designed to analyse the mechanism for the effect of excision on muscle nicotinic receptor kinetics. Accordingly, we do not have a complete data set with low efficacy agonists on the receptors we studied. However, our data from cell-attached patches are qualitatively consistent with the studies of burst duration performed by Bouzat et al. (1994), and support the idea that the major effect of these structural changes is on the channel closing rate.

There are no obvious structural features in these regions which would suggest a mechanism for the change in gating kinetics (sequences scanned using the Prosite profile for protein motifs; Hofmann et al. 1999). Previous studies have shown that a duplication of part of the HA region results in the appearance of distinct kinetic modes for gating of the adult receptor (Milone et al. 1998), and that mutations of residues in the M4 region can alter the channel kinetics of both embryonic and adult receptors (Li et al. 1990; Ortiz-Miranda et al. 1997; Bouzat et al. 1998).

Excision has effects on embryonic type receptors expressed in primary myotubes (Trautmann & Siegelbaum, 1983), mononucleated cells derived from a mouse brain tumour (BC3H1; Covarrubias & Steinbach, 1990), and recombinant receptors stably expressed in quail fibroblasts (QF18 cells; J. H. Steinbach, unpublished observations). These observations, coupled with the present findings from receptors transiently expressed in HEK 293 cells, indicate that there is no muscle-specific interaction which alters the functional properties of embryonic receptors in intact patches. Previous studies have found that the effect of excision was relatively slow to develop, developed at about the same rate at 11 or 22°C, and was not affected by exposure of the cytoplasmic face of the membrane to phosphatases, kinases or ATP (Covarrubias & Steinbach, 1990). Accordingly, it was considered unlikely that an enzymatic reaction underlay the change, and specifically that phosphorylation or dephosphorylation was unlikely. A significant role for divalent cations is unlikely, as the effect of excision is identical when the cytoplasmic solution contained Mg-EGTA (0.1–2.0 mm Mg2+, Covarrubias & Steinbach, 1990) or 1.8 mm Ca2+ plus 1.7 mm Mg2+ (present results). It has been proposed by others that patch excision affects the function of ion channels via changes in the cytoskeleton or its attachment to ion channels. Fukuda et al. (1981) reported that disruption of microfilaments inhibited Na+ channel function while breakdown of microtubules affected Ca2+ channels. Shcherbatko et al. (1999) found that pressure-induced rupture of sites of membrane attachment to underlying cytoskeleton was accompanied by a transition of Na+ channel kinetics to a fast-inactivating mode. In macropatches, this transition was accelerated by agents which prevent microtubule formation.

It is possible that a similar mechanism underlies the excision-elicited decrease in the mean open time in nicotinic receptors. However, it is surprising that the addition of two point mutations in M4 to changes in the HA region is required to give the receptor sensitivity to excision. The two point mutations in the M4 transmembrane domain should be well out of any region responsible for interactions of the receptor with cytoplasmic components (for example, attachment to the cytoskeleton). It is possible that the mutations in M4 change the overall receptor structure in a way that makes yet another site (perhaps the HA region) available for interaction.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ken Paradiso and Steve Sine for stimulating discussions. We thank Cecilia Bouzat, Nina Bren and Steve Sine for the αY93F and chimeric subunit cDNA. J.H.S. is the Russell and Mary Shelden Professor of Anesthesiology. This work was supported by a fellowship from the McDonnell Center for Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology to G.A., and R01 NS22356 to J.H.S.

References

- Akk G, Auerbach A. Inorganic, monovalent cations compete with agonists for the transmitter binding site of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:2652–2658. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79834-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Auerbach A. Activation of muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channels by nicotinic and muscarinic agonists. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;128:1467–1476. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Zhou M, Auerbach A. A mutational analysis of the acetylcholine receptor channel transmitter binding site. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:207–218. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77190-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A. A statistical analysis of acetylcholine receptor activation in Xenopus myocytes: stepwise versus concerted models of gating. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;461:339–378. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A, Akk G. Desensitization of mouse nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channels. A two-gate mechanism. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;112:181–197. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A, Sigurdson W, Chen J, Akk G. Voltage dependence of mouse acetylcholine receptor gating: different charge movements in di-, mono- and unliganded receptors. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:155–170. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Aylwin ML, White MM. Gating properties of mutant acetylcholine receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 1994;46:1149–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzat C, Bren N, Sine SM. Structural basis of the different gating kinetics of fetal and adult acetylcholine receptors. Neuron. 1994;13:1395–1402. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzat C, Roccamo AM, Garbus I, Barrantes FJ. Mutations at lipid-exposed residues of the acetylcholine receptor affect its gating kinetics. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;54:146–153. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Ogden DC. Activation of ion channels in the frog end-plate by high concentrations of acetylcholine. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;395:131–159. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Sakmann B. Fast events in single channel currents activated by acetylcholine and its analogues of the frog muscle end-plate. The Journal of Physiology. 1985;369:501–557. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias M, Steinbach JH. Excision of membrane patches reduces the mean open time of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Pflügers Archiv. 1990;416:385–392. doi: 10.1007/BF00370744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda J, Kameyama M, Yamaguchi K. Breakdown of cytoskeletal filaments selectively reduces Na and Ca spikes in cultured mammal neurones. Nature. 1981;294:82–85. doi: 10.1038/294082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K, Bucher P, Falquet L, Bairoch A. The PROSITE database, its status in 1999. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27:215–219. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Thesleff S. A study of the ‘desensitization’ produced by acetylcholine at the motor end-plate. The Journal of Physiology. 1957;138:63–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney PC, Nowak MW, Zhong W, Silverman SK, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. Dose-response relations for unnatural amino acids at the agonist binding site of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: tests with novel side chains and with several agonists. Molecular Pharmacology. 1996;50:1401–1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Schuchard M, Palma A, Pradier L, McNamee MG. Functional role of the cysteine 451 thiol group in the M4 helix of the γ subunit of Torpedo californica acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5428–5436. doi: 10.1021/bi00475a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maconochie DJ, Steinbach JH. The channel opening rate of adult- and fetal-type mouse muscle nicotinic receptors activated by acetylcholine. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;506:53–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.053bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby KL, Stevens CF. The effect of voltage on the time course of end-plate currents. The Journal of Physiology. 1972;223:151–171. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milone M, Wang HL, Ohno K, Prince R, Fukudome T, Shen XM, Brengman JM, Griggs RC, Sine SM, Engel AG. Mode switching kinetics produced by a naturally occurring mutation in the cytoplasmic loop of the human acetylcholine receptor ɛ subunit. Neuron. 1998;20:575–588. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80996-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Sakmann B. Single-channel currents recorded from membrane of denervated frog muscle fibers. Nature. 1976;260:799–802. doi: 10.1038/260799a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Miranda SI, Lasalde JA, Pappone PA, McNamme MG. Mutations in the M4 domain of the Torpedo californica nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alter channel opening and closing. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1997;158:17–30. doi: 10.1007/s002329900240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, Auerbach A, Sachs F. Estimating single-channel kinetic parameters from idealized patch-clamp data containing missed events. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:264–280. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79568-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, Auerbach A, Sachs F. Maximum likelihood estimation of aggregated Markov processes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1997;264:375–383. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakmann B, Patlak J, Neher E. Single acetylcholine-activated channels show burst-kinetics in presence of desensitizing concentrations of agonist. Nature. 1980;286:71–73. doi: 10.1038/286071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone F, Zhou M, Auerbach A. A re-examination of adult mouse nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel activation kinetics. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:315–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0315v.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbatko A, Ono F, Mandel G, Brehm P. Voltage-dependent sodium channel function is regulated through membrane mechanics. Biophysical Journal. 1999;77:1945–1959. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77036-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM. Molecular dissection of subunit interfaces in the acetylcholine receptor: identification of residues that determine curare selectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1993;90:9436–9440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Claudio T, Sigworth FJ. Activation of Torpedo acetylcholine receptors expressed in mouse fibroblasts. Single channel current kinetics reveal distinct agonist binding affinities. Journal of General Physiology. 1990;96:395–437. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Ohno K, Bouzat C, Auerbach A, Milone M, Pruitt JN, Engel AG. Mutation of the acetylcholine receptor α subunit causes a slow-channel myasthenic syndrome by enhancing agonist binding affinity. Neuron. 1995;15:229–239. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Quiram P, Papanikolau F, Kreienkamp HJ, Taylor P. Conserved tyrosines in the α subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor stabilize quaternary ammonium groups of agonists and curariform antagonists. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:8808–8816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Steinbach JH. Activation of acetylcholine receptors on clonal mammalian BC3H-1 cells by low concentrations of agonist. The Journal of Physiology. 1986;373:129–162. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Steinbach JH. Activation of acetylcholine receptors on clonal mammalian BC3H-1 cells by high concentrations of agonist. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;385:325–359. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautmann A, Siegelbaum SA. The influence of membrane patch isolation on single acetylcholine-channel current in rat myotubes. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-Channel Recording. New York and London: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 473–480. [Google Scholar]

- Wang HL, Auerbach A, Bren N, Ohno K, Engel AG, Sine SM. Mutation in the M1 domain of the acetylcholine receptor α subunit decreases the rate of agonist dissociation. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;109:757–766. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.6.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen J, Auerbach A. Activation of recombinant mouse acetylcholine receptors by acetylcholine, carbamylcholine and tetramethylammonium. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:189–206. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]