Abstract

To investigate the mechanisms by which phorbol esters potentiate transmitter release from mossy fibre terminals we used fura dextran to measure the intraterminal Ca2+ concentration in mouse hippocampal slices.

A phorbol ester, phorbol 12,13-diacetate (PDAc), potentiated the field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) slope. PDAc also enhanced the stimulation-dependent increase of [Ca2+]i in the mossy fibre terminal (Δ[Ca2+]pre). The magnitude of the PDAc-induced fEPSP potentiation (463 ± 57 % at 10 μM) was larger than that expected from the enhancement of Δ[Ca2+]pre (153 ± 5 %).

The Δ[Ca2+]pre was suppressed by ω-agatoxin IVA (ω-AgTxIVA, 200 nM), a P/Q-type Ca2+ channel-specific blocker, by 31 %. The effect of PDAc did not select between ω-AgTxIVA-sensitive and -resistant components.

The PDAc-induced potentiation of the fEPSP slope was partially antagonized by the protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (BIS-I, 10 μM), whereas the Δ[Ca2+]pre was completely blocked by BIS-I. Although the BIS-I-sensitive fEPSP potentiation was accompanied by a reduction of the paired-pulse ratio (PPR), the BIS-I-resistant component was not.

Whole-cell patch clamp recording from a CA3 pyramidal neuron in a BIS-I-treated slice demonstrated that PDAc (10 μM) increased the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs, 259 ± 33 % of control) without a noticeable change in their amplitude (102 ± 5 % of control).

These results suggest that PKC potentiates transmitter release by at least two distinct mechanisms, one Δ[Ca2+]pre dependent and the other Δ[Ca2+]pre independent. In addition, some phorbol ester-mediated potentiation of synaptic transmission appears to occur without activating PKC.

In the hippocampus, the mossy fibre inputs from dentate granule cells form exceptionally large excitatory synapses on the proximal dendrites of CA3 pyramidal cells. Due to this peculiar organization, dynamic changes in their synaptic strength are thought to exert a dominant influence on information processing in the hippocampus (Johnston et al. 1992; Lisman, 1999). The mossy fibre terminal exhibits a presynaptic long-term potentiation (LTP) that is independent of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor activation (Zalutsky & Nicoll, 1990; Johnston et al. 1992) and is partly dependent on protein kinase C (PKC) activation (Son & Carpenter, 1996). A sustained presynaptic potentiation is also induced by diacylglycerol analogues, phorbol esters (Yamamoto et al. 1987; Son & Carpenter, 1996; Kamiya & Yamamoto, 1997), as is generally observed in central and peripheral synapses (Malenka et al. 1986, 1987; Shapira et al. 1987; Majewski & Iannazzo, 1998). Diacylglycerol and phorbol ester bind to the regulatory C1 domain of PKC and serve as activators of several PKC isoforms (Nishizuka, 1992; Newton, 1997). Although the effects of phorbol esters have been attributed to activation of PKC, accumulating evidence indicates that the phorbol ester-induced potentiation of transmitter release is partly PKC independent (Scholfield & Smith, 1989; Redman et al. 1997; Hori et al. 1999). C1 domain-containing proteins such as Munc13-1 are potential presynaptic phorbol ester receptors (Betz et al. 1998; Hori et al. 1999). In fact, binding of phorbol esters to the C1 domain of Munc13-1 enhances transmitter release (Betz et al. 1998).

PKC may potentiate transmitter release through multiple mechanisms (Majewski & Iannazzo, 1998): activation of Ca2+ channels (Shearman et al. 1989; Swartz, 1993; Stea et al. 1995), inhibition of potassium channels (Doerner et al. 1988; Shearman et al. 1989; Hoffman & Johnston, 1998) or direct upregulation of exocytotic mechanisms other than Ca2+ influx (Capogna et al. 1995; Redman et al. 1997; Stevens & Sullivan, 1998; Hori et al. 1999; Yawo, 1999). The multiplicity may be attributed to both the subcellular distribution of PKC isoforms and their substrate specificity (Tanaka & Nishizuka, 1994; Majewski & Iannazzo, 1998). However, the intracellular mechanisms by which PKC potentiates nerve-evoked transmitter release have not been revealed in the mossy fibre terminal.

In this study, we measured the intraterminal Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]pre) of mossy fibre terminals in a hippocampal slice, and provide evidence that phorbol esters potentiate synaptic transmission through at least three distinct mechanisms: (1) enhancement of the stimulation-dependent increase of [Ca2+]pre in the mossy fibre terminal (Δ[Ca2+]pre); this component was inhibited by bisindolylmaleimide I (BIS-I), a selective inhibitor of PKC (Toullec et al. 1991); (2) potentiation of transmitter release without increasing Δ[Ca2+]pre; this component was accompanied by a reduction of the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) and was inhibited by BIS-I; and (3) a BIS-I-resistant potentiation without increasing Δ[Ca2+]pre; this component was not accompanied by a reduction of the PPR. The first and second components appear to involve PKC whereas the third component may be caused by a C1 domain-containing phorbol ester receptor other than PKC.

METHODS

Preparation

All expriments were carried out in accordance with the guiding principles of the Physiological Society of Japan. Postnatal mice (21-28 days old, BALB/c strain) were ether anaesthetized, and the hippocampi were quickly removed from both hemicerebrums. Transverse slices of the hippocampus (0.4 mm thickness) were prepared using a standard technique described previously (Kamiya & Ozawa, 1999), and were incubated for 1 h or more at 33°C in standard artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (mM): NaCl, 126; NaHCO3, 26; NaH2PO4, 1; KCl, 3; CaCl2, 2; MgCl2, 1; glucose, 11 (pH 7.4 with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2). In all experiments [Ca2+]o was increased by adding CaCl2 without changing other ions and was reduced by adding Na2EGTA, calculating free [Ca2+]o from the dissociation constant. The following experiments were done at 30-33°C unless otherwise noted.

Extracellular recordings

Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded in the stratum lucidum of the CA3 region using glass microelectrodes with tip diameters of less than 10 μm, which were filled with standard ACSF. The silver bipolar stimulating electrode was placed in the granule cell layer. In each experiment, the positions of both the stimulating and recording electrodes were adjusted until the fEPSP met criteria described previously (Zalutsky & Nicoll, 1990). Twin pulses of 0.2 ms duration and an interpulse interval of 40 ms were applied at 0.1 Hz. The fEPSP slope was calculated by least-squares linear regression over a 1 ms bin period. The minimum value during the first falling phase of the fEPSP was adopted as the representative fEPSP slope. For comparison, the fEPSP slope was normalized to the control mean. The change of the presynaptic volley was negligible throughout the experiments.

Measurement of intraterminal Ca2+ concentration

A glass pipette with an approximately 100 μm tip diameter was dipped in a solution of fura-2-conjugated dextran (fura dextran, MW 3000, Molecular Probes Inc.) at a concentration of 10 mg ml−1, dried at 4°C and stored at -20°C. A transverse slice of the hippocampus was mounted in an interface chamber. The fura dextran-containing glass pipette was inserted into the granule cell layer of the slice for 10 min. Similar results were obtained from some experiments in which the pipette was inserted in the stratum lucidum at the CA4 region instead of the granule cell layer. The slice was then incubated for 3-6 h at 33°C in standard ACSF in order to allow the dye to be transported to the mossy fibre terminals. The stimulating bipolar electrode was positioned at the injected site. A conventional epifluorescence system equipped with a water-immersion objective (× 40, NA 0.7, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and Xenon lamp (150 W) was focused on the mossy fibre terminals in the stratum lucidum at the CA3 region. Fluorescence was excited alternately at wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm through the minimum iris orifice (diameter, 50 μm). As there is a window (diameter, 50 μm) in front of the photomultiplier tube (OSP-3, Olympus), the background fluorescence behind the focal plane was reduced. The intraterminal Ca2+ was calculated from the ratio of fluorescence intensities at wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985) using the dissociation constant (KD) determined by the manufacturer (389 nM) and the system-dependent parameters determined by a conventional in situ calibration method. This experimental value was represented as [Ca2+]pre, the variation of which must be discriminated from the real time- and space-dependent variation of [Ca2+]i. The signal was sampled at 10-100 Hz by a computer (PC-9801RS, NEC) with software for measuring intracellular Ca2+ (MiCa, provided by Drs K. Furuya & K. Enomoto, National Institute of Physiological Science, Japan). The mean fluorescence intensity during 1 s just before stimulation was used for the calculation of basal [Ca2+]pre. The mean fluorescence intensity during 300 ms just after the nerve stimulation-dependent increment was used for calculating the peak [Ca2+]pre, and the difference between the peak and basal [Ca2+]pre was defined as Δ[Ca2+]pre. For comparisons, the Δ[Ca2+]pre was normalized to the control mean.

Throughout all experiments, D(-)2-aminophosphonopentanoic acid (AP5; 25 μM) was used to block possible contamination from NMDA-dependent processes. At the end of each experiment a type 2 metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist, DCG-IV (1 μM), was bath applied to stimulate the metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR2/3) which is selectively expressed in the mossy fibre terminal (Kamiya & Ozawa, 1999). If this treatment did not diminish the fEPSP slope to less than 50 % of that before the application of DCG-IV, the data were excluded from the following analyses. Most experiments fitted these criteria. In standard ACSF DCG-IV diminished Δ[Ca2+]pre to 72 ± 4 % of control (n = 6) as expected from the non-linear relationship between the Δ[Ca2+]pre and fEPSP (Kamiya & Ozawa, 1999). Once the basal [Ca2+]pre exceeded 500 nM, the data were excluded from the following analyses. Repeat experiments were made in another laboratory using a membrane-permeant Ca2+ indicator, rhod-2 AM (Dojindo Laboratory, Kumamoto, Japan), which was loaded into the mossy fibre terminals without injuring the granule cells (Kamiya & Ozawa, 1999). The results were similar to those with fura dextran (H. Kamiya, unpublished observations).

Recording of miniature EPSCs

Whole-cell recordings were made from CA3 pyramidal neurons as described (Kamiya & Ozawa, 1999). The membrane currents were recorded at -70 mV in the presence of 0.5 μM tetrodotoxin and 100 μM picrotoxin. Patch pipettes were filled with an internal solution (pH 7.2) containing (mM): caesium gluconate, 150; EGTA, 0.2; NaCl, 8; Hepes, 10; MgATP, 2; and QX-314, 5 (Sigma-Aldrich). Detection criteria included an amplitude of 8 pA and an area threshold of 10 fC. The effect of PDAc in the presence of BIS-I on either the amplitude or inter-event interval was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Reagents

Pharmacological agents were usually bath applied through a perfusion line at a constant flow rate. The solution in the chamber (ca 1 ml) was completely replaced in less than 2 min. Agents used in this study and their sources were as follows: D(-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5, Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK); 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX, Tocris Cookson); (2S,2′R,3′R)2-(2′,3′-dicarboxycyclopropyl)glycine (DCG-IV, Tocris Cookson); phorbol 12,13-diacetate (PDAc, Wako, Osaka, Japan); 4α-phorbol (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA); bisindolylmaleimide I (BIS-I, Calbiochem); forskolin (Research Biochemicals International, Natick, MA, USA); 3-isobuty-1-methylxanthine (IBMX, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA); ω-conotoxin GVIA (ω-CgTxGVIA, Peptide Institute Inc., Minoh, Japan); ω-agatoxin IVA (ω-AgTxIVA, Peptide Institute Inc.); nimodipine (Research Biochemicals International). The effects of BIS-I were assessed after 1 h preincubation which had little effect on the first fEPSP amplitude (data not shown). CNQX, PDAc, 4α-phorbol, BIS-I, forskolin and nimodipine were dissolved in DMSO, then diluted. The concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.2 %, and by itself had no effect on the fEPSP and [Ca2+]pre. The stock solutions of ω-CgTxGVIA and ω-AgTxIVA were each prepared at a concentration of 1 mM and 0.1 mM in an extracellular solution containing 100 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich). The stock solution was added directly to the recirculating perfusion solution saturated with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2.

The values in the text and figures are means ±s.e.m. (n = number of experiments). Unless otherwise noted, statistically significant differences between various parameters were determined using Student's two-tailed t test between raw data for the paired experiments and the Mann-Whitney U test for unpaired experiments. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

[Ca2+]pre in the mossy fibre terminal

When injected into the granule cell layer in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (Fig. 1A1), the Ca2+-sensitive dye fura dextran diffused into the injured neurons and was allowed to accumulate in the terminals during an incubation time of 3-6 h. Figure 1A2 shows a fluorescence image of fura dextran in the hippocampal slice. The fluorescence-labelled axons were all in a narrow bundle (Fig. 1A2), as long as 1.0 mm, in the stratum lucidum from the injected site to the terminal boutons (Fig. 1A2 and A3), indicating that the mossy fibres were specifically labelled. The large mossy fibre terminals were easily recognizable like bright stars in a galaxy (Fig. 1B). We never observed neuronal somata retrogradely labelled with fura dextran in the CA3 region. A photomultiplier was focused in the CA3 on a small circular region with a diameter of 50 μm which contained several large fluorescence terminals (Fig. 1C). The fluorescence signals were monitored by alternating the excitation wavelength between 340 and 380 nm, and the [Ca2+]pre was quantified by the ratio of their fluorescence intensities (Fig. 1D). Although mossy fibres contain small terminals at GABAergic interneurons, the volume ratio suggests that at least 80 % of the fluorescence should come from the large terminals at the CA3 pyramidal cell dendrites (Acsády et al. 1998). The results were almost identical from a smaller area (10 μm in diameter) containing only a single large bouton (n = 9). Upon invasion of the action potential, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels were activated, leading to an increase in [Ca2+]pre (Fig. 1D). With standard ACSF containing 2 mM Ca2+ and 1 mM Mg2+, the resting [Ca2+]pre was 139 ± 30 nM (n = 20); [Ca2+]pre increased by 14.9 ± 1.5 nM (n = 7) following a single nerve stimulus.

Figure 1. Measurement of the intraterminal Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]pre) of mossy fibre terminals in a mouse hippocampal slice.

A, explanation of labelling method. A1, a glass pipette containing fura-2-conjugated dextran (fura dextran) was inserted in the dentate granule cell layer. A2, the same area under the epifluorescence light at 360 nm. The whole length of mossy fibres as well as their terminals were labelled with fura dextran after 4 h incubation. A3, overlap view of A1 and A2, showing that the fura dextran fluorescence was restricted to the stratum lucidum. B, enlarged view of mossy fibre terminals labelled with fura dextran. The lower left is the CA3 pyramidal cell layer that is unlabelled. C, enlarged view of the recording area. The epifluorescence light at 380 nm was focused on a small area (circled) containing several large boutons. D: top two traces, changes of fluorescence in the recording area in response to a single presynaptic stimulation measured by excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm. Bottom, [Ca2+]pre calculated from the ratio of their fluorescence intensities. All three traces are stimulation-triggered averages of 10 records. E, relationship between number of pulses in a train at 50 Hz and the stimulus-dependent increment of [Ca2+]pre (Δ[Ca2+]pre) which was normalized to the value at a single pulse. In this and all subsequent figures each plotted symbol (or column) with a bar indicates the mean ± s.e.m. The line was drawn as a least-squares fit to values between 1 and 20 pulses. F, relationship between [Ca2+]o and Δ[Ca2+]pre in response to 10 pulses at 50 Hz, normalized to the mean at 2 mM [Ca2+]o.

Although [Ca2+]i transients should be much larger and faster in the vicinity of Ca2+ channel clusters (Zucker, 1996; Neher, 1998), the volume-averaged fura-2 signal is related to the magnitude of Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ channels (Sinha et al. 1997). In fact, the stimulation-dependent accumulation of [Ca2+]pre (Δ[Ca2+]pre) was dependent on the number of pulses in a train with high frequency (Fig. 1E). At 50 Hz, Δ[Ca2+]pre was almost proportional to the number of pulses in a train when it was below 20, but became non-linear above 20. In Fig. 1F, the dependence of Δ[Ca2+]pre on [Ca2+]o was also investigated. Although the relationship was non-linear, Δ[Ca2+]pre was sensitive to [Ca2+]o between 1-4 mM. Unless otherwise indicated, all other experiments were performed in 2 mM [Ca2+]o. In addition, Δ[Ca2+]pre was reversibly suppressed by a GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen (data not shown), which inhibits transmitter release by reducing Ca2+ influx into the presynaptic terminal (Wu & Saggau, 1997). These results suggest that Δ[Ca2+]pre is sensitive to the change in Ca2+ influx during this type of neuromodulation.

Mechanisms of phorbol ester-induced potentiation

A phorbol ester, phorbol 12,13-diacetate (PDAc), potentiated the field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) recorded from the stratum lucidum of the CA3 region, as shown in Fig. 2A and B. A sustained potentiation was observed 20 min or more after removal of PDAc. The potentiation was usually accompanied by a reduction of the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) (Fig. 2A and C), consistent with previous studies indicating that PDAc-dependent potentiation is presynaptic at the mossy fibre-CA3 synapse (Yamamoto et al. 1987). On average the addition of 10 μM PDAc significantly potentiated the fEPSP slope to a value 463 ± 57 % of that at 2 mM [Ca2+]o (Fig. 2B; P < 0.001) and significantly reduced the PPR from 2.55 ± 0.18 to 0.92 ± 0.03 (Fig. 2C; P < 0.001). Even when the stimulation strength was attenuated in order to evoke fEPSP at a comparable amplitude, the reduction of the PPR was again significant (1.18 ± 0.06, P < 0.001).

Figure 2. Phorbol-ester induced potentiation of the field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP).

A, sample records of field potential and its time derivative in response to twin pulses of 40 ms interval: top two traces, control fEPSP and fEPSP slope; bottom two traces, fEPSP and fEPSP slope after 10 min exposure to 10 μM phorbol 12,13-diacetate (PDAc). The paired-pulse ratio (PPR) was calculated as the second fEPSP slope divided by the first fEPSP slope, and was 2.95 during control and 0.98 after the PDAc-induced potentiation. The fibre volley responses are indicated by *. B, summary of the effects of PDAc (10 μM, bar) on the first fEPSP slope which was normalized to the mean value before exposure to PDAc (n = 10). At the arrow the stimulation intensity was attenuated so as to adjust the first fEPSP amplitude to the control. Finally, 1 μM DCG-IV was applied to determine whether the recordings fitted the criteria of the mossy fibre response (see Methods). The fEPSP was abolished by CNQX (10 μM) and only the fibre volley response remained. C, time-dependent plot of the PPR from B.

To determine whether PDAc potentiates transmitter release by increasing Ca2+ influx into the presynaptic terminal during presynaptic stimulation, the effects of PDAc on fEPSP and Δ[Ca2+]pre were compared. Figure 3A shows a sample record of [Ca2+]pre in response to a single electrical stimulus. Exposure to 10 μM PDAc increased the Δ[Ca2+]pre, reaching a steady state within 10 min. On average PDAc enhanced the Δ[Ca2+]pre to a value 153 ± 5 % of control (n = 7, P < 0.001). In the following experiments, the Δ[Ca2+]pre was evoked by a 10-pulse train at 50 Hz in order to increase the signal:noise ratio. PDAc again enhanced the Δ[Ca2+]pre to a mean value 140 ± 4 % of control (Fig. 3B; P < 0.002). The results were not significantly different from those using a single electrical pulse as a stimulus. This is consistent with the observation that the enhanced Δ[Ca2+]pre was also proportional to the number of pulses in a train when it was less than 10 (data not shown). The mean time course of Δ[Ca2+]pre enhancement during exposure to PDAc (Fig. 3B) was somewhat faster than that of the mean fEPSP slope potentiation (Fig. 2B). The reason for this difference is unknown.

Figure 3. Phorbol ester-induced augmentation of Δ[Ca2+]pre.

A, sample records of [Ca2+]pre before (Control) and after 10 min exposure to 10 μM PDAc. Each trace is a stimulation-triggered average of 10 records in response to a single presynaptic stimulation. B, summary of the effect of PDAc on normalized Δ[Ca2+]pre (n = 6). PDAc (10 μM) was bath applied as indicated (bar). Subsequent application of 1 μM DCG-IV reduced the Δ[Ca2+]pre. C, summary of the effects of PDAc on the decay time constant of Δ[Ca2+]pre (n = 7); control before exposure to PDAc (left) and after 10 min exposure to 10 μM PDAc (right). The difference was statistically significant (*P < 0.005, paired t test).

Since about 5-10 boutons were included in the 50 μm diameter recording area, the apparent increase of Δ[Ca2+]pre might have resulted from an increased number of active terminals in the recording area. To test this, we recorded the fluorescence from a small recording area 10 μm in diameter which contained only a single large bouton. In all seven boutons tested at 2 mM [Ca2+]o, PDAc faithfully increased the Δ[Ca2+]pre on average to 136 ± 7 % of control (P < 0.002). The results were almost the same as those from the 50 μm diameter recording area.

Following the stimulus-induced increase, [Ca2+]pre decayed slowly as shown in Fig. 3A. The falling phase between 0-5 s was fitted to a single exponential function. At 2 mM [Ca2+]o, the falling phase time constant τ was 939 ± 81 ms. If PDAc decelerates intracellular Ca2+ sequestration, an increase of τ would be expected. However, as shown in Fig. 3C, τ was actually significantly reduced in PDAc (P < 0.005). In addition, the resting [Ca2+]pre was not affected by PDAc (n = 7). There is, thus, no evidence of a deceleration of intracellular Ca2+ buffering or removal.

The difference between the effects of PDAc on the fEPSP slope and on Δ[Ca2+]pre may be attributed to the non-linear relationship between presynaptic Ca2+ influx and transmitter release (Dodge & Rahamimoff, 1967) and/or to an additional modulation of the exocytotic machinery downstream of Ca2+ influx (Yawo, 1999). Actually, when [Ca2+]o was varied with constant [Mg2+]o, the fEPSP slope changed with a non-linear relationship (Fig. 4A) which was well fitted to the Dodge-Rahamimoff equation as follows:

| (1) |

where ymax is the maximum value of the normalized fEPSP slope (5.94) and KD’ is the apparent dissociation constant (1.57 mM). The least-squares approximation of the co-operativity integer, n, was 3. According to the relationship between [Ca2+]o and Δ[Ca2+]pre (Fig. 1F), the relationship between the fEPSP slope and Δ[Ca2+]pre was obtained as in Fig. 4B, which could be approximated by a power function (Kamiya & Ozawa, 1999):

| (2) |

Figure 4. Comparison between PDAc-induced fEPSP potentiation and Δ[Ca2+]pre.

A, [Ca2+]o dependence of fEPSP slope (n = 5). The fEPSPs were evoked in response to twin electrical pulses with an interval of 40 ms at 0.1 Hz applied to the dentate granule cell layer. The first fEPSP slope was normalized to the mean at 2 mM [Ca2+]o. The line was drawn according to the Dodge-Rahamimoff relation of y = 5.94(x/(x + 1.57))3. B, relationship between fEPSP slope and Δ[Ca2+]pre. Data from control experiments (○) were derived from those used in Figs 1F and 4A. •, ▴ were obtained after 10 min exposure to 0.5 μM (▴; n = 7 for fEPSP slope; n = 6 for Δ[Ca2+]pre) or 10 μM PDAc (•; n = 10 for fEPSP slope; n = 6 for Δ[Ca2+]pre). Note that [Ca2+]o was held at 2 mM in the PDAc experiments. For the fEPSP, the effects of PDAc were significant at both 0.5 μM (P < 0.02) and 10 μM (P < 0.001). For the Δ[Ca2+]pre, the effects of PDAc were significant at both 0.5 μM (P < 0.02) and 10 μM (P < 0.002). C, relationship between PPR and Δ[Ca2+]pre from the same experiments shown in Fig. 4B. The PPR was normalized to the mean at 2 mM [Ca2+]o which was almost identical among the different series of experiments. For the PPR, the effects of PDAc were significant at both 0.5 μM (P < 0.005) and 10 μM (P < 0.001).

The power (m) was estimated to be 2.5 for [Ca2+]o between 1 and 8 mM. When the experimental values of the fEPSP slope and Δ[Ca2+]pre were plotted after exposure to PDAc on the same graph of Fig. 4B, they deviated markedly at both 0.5 and 10 μM from those obtained by changing [Ca2+]o. Therefore, the potentiating effects of PDAc might not be simply the result of the enhancement of Ca2+ influx (Wu & Saggau, 1997; Kamiya & Ozawa, 1999).

The PPR was positively dependent on [Ca2+]o below 4 mM whereas it was negatively dependent on [Ca2+]o above 4 mM. As a result, the relationship between Δ[Ca2+]pre and PPR was biphasic as shown in Fig. 4C. Although it is premature to discuss this relationship, the positive phase might be explained by the fact that facilitation is upregulated by residual [Ca2+]i (Kamiya & Zucker, 1994; Delaney & Tank, 1994) and the negative phase could be attributed to depression either through depletion of the readily releasable pool of vesicles or through refractoriness of release sites (Neher, 1998; Dittman et al. 2000). When the experimental values of PPR and Δ[Ca2+]pre were plotted after exposure to PDAc on the same graph of Fig. 4C, they deviated markedly at both 0.5 and 10 μM from those obtained by changing [Ca2+]o, even when considering the effect of a fEPSP size of 133 % (Fig. 2C). These results also suggest that PDAc potentiates the fEPSP through mechanisms other than by enhancing Ca2+ influx. Since the difference between 0.5 and 10 μM PDAc was quantitative rather than qualitative, we usually applied PDAc at 10 μM in the following experiments to see the clear effects of the phorbol ester.

Ca2+ channel toxin sensitivities of the phorbol ester-induced potentiation

If PDAc preferentially upregulates a subtype of Ca2+ channels, the PDAc sensitivity of Δ[Ca2+]pre would be expected to increase or decrease after treatment with a channel subtype-specific toxin. As shown in Fig. 5A, the Δ[Ca2+]pre was not clearly reduced by 10 μM ω-CgTxGVIA (N-type specific channel blocker) in 5 of 13 experiments. In eight other experiments, ω-CgTxGVIA inhibited Δ[Ca2+]pre to a steady-state level of 72-93 % of control in 10 min. In summary, the effect of 10 μM ω-CgTxGVIA on the Δ[Ca2+]pre was inconsistent. On the other hand, Δ[Ca2+]pre was clearly reduced by ω-AgTxIVA (P/Q-type specific channel blocker) as shown in Fig. 5A and B, with the maximum effect at 200 nM. The remaining component was sensitive to neither nimodipine (10 μM, 91 ± 5 % of value before treatment, n = 6) nor Ni2+ (50 μM, 98 ± 3 % of value before treatment, n = 7). Kamiya & Ozawa (1999) reported that ω-CgTxGVIA reduced Δ[Ca2+]pre to 60-70 % of control in the hippocampal mossy fibre terminals of younger mice (10-18 days old). Therefore, the toxin sensitivity of mossy fibre terminals changes with development (see Iwasaki et al. 2000). Exposure to 10 μM PDAc enhanced the ω-CgTxGVIA-resistant component of Δ[Ca2+]pre to 137 ± 8 % of the control amplitude, the ω-AgTxIVA-resistant component to 146 ± 6 % of the control amplitude and the residual component to 138 ± 7 % of the control amplitude, respectively (Fig. 5C). Therefore, PDAc effects did not select between the AgTxIVA-sensitive and -resistant components.

Figure 5. PDAc responsiveness among Ca2+ channel subtypes.

A, effects of Ca2+ channel antagonists on the Δ[Ca2+]pre and its enhancement by PDAc. Δ[Ca2+]pre was normalized to the mean value during the control period (n = 4). The following substances were added to the recirculating solution at the time points indicated by arrows: ω-conotoxin GVIA (ω-CgTxGVIA, 10 μM), ω-agatoxin IVA (ω-AgTxIVA, 200 nM), PDAc (10 μM), nimodipine (Nim, 10 μM), Ni2+ (50 μM) and EGTA (5 mM) (all numbers quoted at final concentrations). The Δ[Ca2+]pre was reduced by addition of ω-AgTxIVA to 59 ± 4 % of control, and was enhanced by a following exposure to PDAc by 33 ± 7 %. Δ[Ca2+]pre was almost insensitive to ω-CgTxGVIA, nimodipine and Ni2+. B. summary of the effects of Ca2+ channel toxins. Δ[Ca2+]pre was normalized to the mean value before toxin exposure (*significant effect); 10 μM ω-CgTxGVIA (left, n = 13), 200 nM ω-AgTxIVA (middle, n = 12, P < 0.005) and both (right, n = 8). C, summary of the effects of PDAc (10 μM) on the toxin-resistant component of Δ[Ca2+]pre. Δ[Ca2+]pre was normalized to the value before exposure to PDAc (*significant effect) in the presence of 10 μM ω-CgTxGVIA (left, n = 7, P < 0.02), 200 nM ω-AgTxIVA (middle, n = 12, P < 0.001) or both (right, n = 6, P < 0.005).

Effects of PKC inhibitors

Although PDAc as low as 0.5 μM consistently potentiated the fEPSP and enhanced the Δ[Ca2+]pre, the inactive analogue 4α-phorbol (10 μM) did not enhance the fEPSP slope (101 ± 6 % of control; n = 5), did not affect the PPR (from 2.40 ± 0.08 to 2.43 ± 0.15; n = 5), and had no effect on Δ[Ca2+]pre (100 ± 2 % of control; n = 6).

To determine whether the PDAc-induced potentiation is mediated by PKC or non-PKC phorbol ester receptors, we investigated the effects of a PKC-selective inhibitor, bisindolylmaleimide I (BIS-I), which is structurally similar to staurosporine and acts as a competitive inhibitor for the kinase domain of PKC (Toullec et al. 1991). As shown in Fig. 6A, after 1 h preincubation in ACSF containing 10 μM BIS-I, the fEPSP was potentiated by exposure to 10 μM PDAc in the presence of BIS-I. Although PDAc potentiated the fEPSP to a mean of 258 ± 34 % of control in the presence of BIS-I, this effect was significantly less potent than in the presence of vehicle alone (0.1 % DMSO, Fig. 6B). The PPR was significantly reduced by PDAc in the vehicle-alone experiments, but was not reduced in the BIS-I experiments (Fig. 6A and C). The effects of PDAc were negligible at a concentration of 0.5 μM in the BIS-I-treated slice: the fEPSP slope after exposure to 0.5 μM PDAc was 97 ± 2 % of control (n = 6). BIS-I almost abolished the PDAc-dependent enhancement of Δ[Ca2+]pre (Fig. 6D). Therefore, the BIS-I-resistant component does not appear to be accompanied by an enhancement of Δ[Ca2+]pre. When BIS-I was removed, both the fEPSP slope and the Δ[Ca2+]pre showed a tendency to be potentiated, suggesting that the effects of BIS-I are reversible.

Figure 6. Protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent and -independent components of fEPSP potentiation.

A, sample records of the fEPSP in the bisindolylmaleimide I (BIS-I)-treated slice; before (Control), after 10 min exposure to 10 μM PDAc and after the addition of DCG-IV (1 μM) and CNQX (10 μM). In B–D, the hatched columns indicate the presence of PDAc. B, summary of the effects of BIS-I on the PDAc-induced potentiation of the fEPSP slope. Normalized fEPSP slopes were measured after 10 min in PDAc: left, 7 experiments using vehicle (0.1 % DMSO) alone; right, 16 experiments in the presence of 10 μM BIS-I. The effects of PDAc were significant (*) for both vehicle alone (P < 0.01) and BIS-I (P < 0.001). The difference between vehicle alone and BIS-I was also significant (P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U test). C, effects of PDAc on PPR in vehicle alone (left, n = 7) and in BIS-I-treated slices (right, n = 16). PPRs were measured before (□) and after ( ) 10 min exposure to PDAc. The effect of PDAc was significant in vehicle alone (*P < 0.005), but not in BIS-I. D, summary of the effects of BIS-I on the PDAc-induced enhancement of Δ[Ca2+]pre. Normalized Δ[Ca2+]pre was measured after 10 min in PDAc: left, 6 experiments, vehicle alone; right, 9 experiments in BIS-I. The effect of PDAc was significant (*) in vehicle alone (P < 0.002), but not in BIS-I. The difference between vehicle alone and BIS-I was also significant (P < 0.005). In E and F, the hatched columns indicate the presence of forskolin and IBMX. E, summary of the effects of BIS-I on the forskolin-induced potentiation of the fEPSP slope. Normalized fEPSP slope was measured after 10 min exposure to 50 μM forskolin and 100 μM IBMX: left, 6 experiments using the vehicle (0.1 % DMSO) alone; right, 6 experiments in the presence of 10 μM BIS-I. The effects of forskolin were significant (*) for both vehicle alone (P < 0.05) and BIS-I (P < 0.01). The difference between vehicle alone and BIS-I was not significant. F, effects of forskolin on PPR in vehicle alone (left, n = 6) and BIS-I (right, n = 6). PPRs were measured before (□) and after (

) 10 min exposure to PDAc. The effect of PDAc was significant in vehicle alone (*P < 0.005), but not in BIS-I. D, summary of the effects of BIS-I on the PDAc-induced enhancement of Δ[Ca2+]pre. Normalized Δ[Ca2+]pre was measured after 10 min in PDAc: left, 6 experiments, vehicle alone; right, 9 experiments in BIS-I. The effect of PDAc was significant (*) in vehicle alone (P < 0.002), but not in BIS-I. The difference between vehicle alone and BIS-I was also significant (P < 0.005). In E and F, the hatched columns indicate the presence of forskolin and IBMX. E, summary of the effects of BIS-I on the forskolin-induced potentiation of the fEPSP slope. Normalized fEPSP slope was measured after 10 min exposure to 50 μM forskolin and 100 μM IBMX: left, 6 experiments using the vehicle (0.1 % DMSO) alone; right, 6 experiments in the presence of 10 μM BIS-I. The effects of forskolin were significant (*) for both vehicle alone (P < 0.05) and BIS-I (P < 0.01). The difference between vehicle alone and BIS-I was not significant. F, effects of forskolin on PPR in vehicle alone (left, n = 6) and BIS-I (right, n = 6). PPRs were measured before (□) and after ( ) 10 min exposure to forskolin and IBMX. The effect of forskolin was not significant in either condition.

) 10 min exposure to forskolin and IBMX. The effect of forskolin was not significant in either condition.

Transmitter release from mossy fibre terminals is dependent on cAMP and potentiated by forskolin (Weisskopf et al. 1994; Huang et al. 1994). Forskolin (50 μM) potentiated the fEPSP slope to 529 ± 100 % of control in the presence of 100 μM IBMX (Fig. 6E). In contrast to PDAc-induced potentiation, forskolin-induced potentiation was not accompanied by a significant reduction of the PPR (Fig. 6F). To investigate the specificity of BIS-I, forskolin-induced potentiation of fEPSP was investigated in the presence of 10 μM BIS-I after 1 h preincubation. As shown in Fig. 6E, the effects of BIS-I on forskolin-induced potentiation were negligible, consistent with the hypothesis that the effect of BIS-I was specific to PKC. Figure 6F indicates that the effect of BIS-I on the PPR was also negligible.

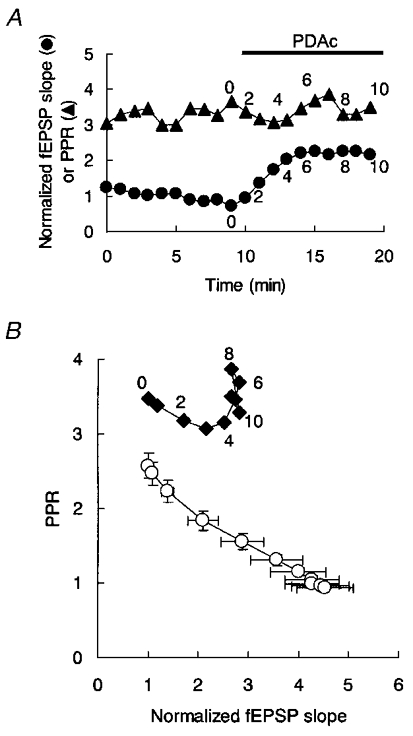

During PDAc-induced potentiation, the PPR was always decreased from its initial value throughout the course of the potentiation (Fig. 2C). However, this was not the case in the BIS-I-treated slice (Fig. 7A). In BIS-I, the PPR was initially 2.29 ± 0.21 (n = 16), in the same range as in the absence of BIS-I, but subsequent exposure to PDAc (10 μM) no longer reduced the PPR (Fig. 7A), although it continued to potentiate the fEPSP slope (Fig. 6B). To show this clearly, the PPR was plotted against the fEPSP slope during a 10 min exposure to PDAc (Fig. 7B). For the control experiment shown in Fig. 2C, the PPR was reduced along with the enhancement of the fEPSP slope (○, Fig. 7B) with a correlation coefficient of -0.97 ± 0.006 (n = 17). However the correlation between the PPR and the fEPSP slope in the BIS-I-treated slice was on average only -0.36 ± 0.13 (n = 16, Fig. 7B), significantly less than in the absence of BIS-I. If PDAc upregulated the fusion probability during synaptic vesicle exocytosis, a reduction of the PPR would be expected (see Discussion). Therefore, the BIS-I-resistant component of fEPSP potentiation appears not to have been accompanied by an upregulation of fusion probability, thereby being different from the BIS-I-sensitive component.

Figure 7. Effects of BIS-I on the PDAc-dependent reduction of the PPR.

A, time course of the normalized fEPSP slope (•) and PPR (▴) during PDAc-induced potentiation in 10 μM BIS-I. Numbers in A and B indicate minutes after exposure to PDAc (horizontal bar). B, PPR as a function of the normalized fEPSP slope during the course of PDAc-induced potentiation shown in A (♦). The data shown in Fig. 2B and C were re-plotted for comparison (○). In the absence of BIS-I, correlation coefficients between the PPR and the normalized fEPSP slope were similar for both 0.5 μM and 10 μM PDAc.

It has been shown that phorbol ester-induced potentiation is presynaptic (Yamamoto et al. 1987). To confirm this in the presence of BIS-I, the effect of PDAc on the amplitude of the miniature excitatory synaptic current (mEPSC) was examined in a CA3 pyramidal neuron under whole-cell voltage clamp at -70 mV. Since axonal action potentials and GABAA-mediated synaptic responses were blocked in the presence of both tetrodotoxin and picrotoxin, the intermittent inward deflections of current were regarded as mEPSCs mediated by the spontaneous release of glutamate (Fig. 8A, top trace). Consistent with this hypothesis, the AMPA-type glutamate receptor antagonist CNQX completely abolished current deflections above the noise level (Fig. 8A, bottom trace). Exposure to 10 μM PDAc increased the frequency of mEPSCs even in the presence of 10 μM BIS-I without a noticeable change in their amplitude (Fig. 8A, middle trace and Fig. 8B). When cumulative probability plots of mEPSC amplitude were compared before and after exposure to PDAc (Fig. 8C), the difference was insignificant in all 11 cells tested. On the other hand, cumulative probability plots of inter-event intervals (Fig. 8D) showed a significant difference before and after exposure to PDAc (P < 0.05) in all cells. In summary, PDAc had negligible effects on mean mEPSC amplitude, but enhanced mEPSC frequency. These results are consistent with the notion that the BIS-I-resistant component of PDAc-induced potentiation is presynaptic.

Figure 8. Miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) in the presence of BIS-I.

A, sample records of mEPSCs in a CA3 pyramidal cell at a holding potential of -70 mV. In each, 10 traces are superimposed. Top, control records in BIS-I (10 μM). Middle, PDAc (10 μM) treatment in BIS-I. Bottom, after addition of CNQX (10 μM). B, amplitude histogram of mEPSCs in BIS-I (▪) and in both BIS-I and PDAc (□). C, cumulative probability plots of mEPSC amplitudes for a representative experiment of BIS-I (continuous line) and in both BIS-I and PDAc (dotted line). The difference between the two distributions was insignificant (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). D, cumulative probability plots of inter-event intervals for the same data in BIS-I (continuous line) and in both BIS-I and PDAc (dotted line). The difference between the two distributions was significant (P < 0.001). In 11 experiments with BIS-I, PDAc had no significant effect on mean mEPSC amplitude (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) but did significantly affect mean mEPSC frequency (P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Three components of phorbol ester-dependent potentiation

If the potentiation of the fEPSP slope occurs presynaptically, it could be caused by an increased magnitude of transmitter release and/or an increased synchrony of release. Neurotransmitter release is regulated by the number of docked/primed vesicles that are readily releasable (readily releasable pool) and by the fusion probability (Rosenmund & Stevens, 1996). Depolarization of the nerve terminal activates voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, leading to a local increase in [Ca2+]i, and Ca2+ binds to the putative ‘Ca2+ sensor’, which regulates the fusion probability (Augustine et al. 1987). The present results indicate that the phorbol ester PDAc increased the Δ[Ca2+]pre (Fig. 3) even in a single mossy fibre terminal. However, PDAc potentiated the fEPSP more than expected from the increase of Δ[Ca2+]pre (Fig. 4). PDAc also reduced the PPR to a value less than that expected from the enhancement of Ca2+ influx (Fig. 4). A simple explanation is that PDAc also potentiates the fEPSP with a reduction of the PPR through a mechanism other than increasing the action potential-dependent increment of presynaptic [Ca2+]i. This is consistent with a previous finding in a synaptosome preparation enriched with mossy fibre terminals that phorbol esters enhance Ca2+-dependent glutamate release without changing the high K+-induced [Ca2+]i increment (Terrian, 1995), and with the demonstration that ionomycin-evoked glutamate release is enhanced by PKC activation (Zhang et al. 1996). However, we could not exclude the possibility that one subtype of Ca2+ channels is located closer to the vesicles than others and is selectively upregulated by PDAc, thus enhancing the fEPSP to a level higher than would be expected from the bulk increase of Δ[Ca2+]pre.

If the latter is the case, it is expected that the PDAc effect would select between the Ca2+ channel toxin-sensitive and -resistant components. The Δ[Ca2+]pre of the mossy fibre terminal consists of a ω-AgTxIVA-sensitive (P/Q-type) component and a component resistant to both ω-CgTxGVIA and ω-AgTxIVA and insensitive to nimodipine and Ni2+ (Fig. 5). The effects of ω-CgTxGVIA were inconsistent. The ω-AgTxIVA sensitivity of the Δ[Ca2+]pre was less than that expected from the toxin sensitivity of the EPSP (Castillo et al. 1994). Although toxin sensitivity may vary with developmental stage and species, the ω-AgTxIVA-sensitive Ca2+ channels were shown to couple with transmitter release more efficiently than others in hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses (Wu & Saggau, 1997). In our study the effect of ω-AgTxIVA was saturated at 200 nM, but there remains a possibility that another channel subtype is also sensitive to ω-AgTxIVA at micromolar levels. Additional experiments are necessary to clarify these possibilities in this preparation. Since PDAc effects did not select between the AgTxIVA-sensitive and -resistant components (Fig. 5), we have no evidence for the presence of Ca2+ channel clusters preferentially upregulated by PDAc. In two additional experiments we tested the ω-CgTxGVIA sensitivity after the PDAc-induced enhancement of Δ[Ca2+]pre, but Δ[Ca2+]pre was not sensitive to ω-CgTxGVIA in either experiment (100 and 104 % of the value before ω-CgTxGVIA treatment). This argues against the notion that PDAc promotes the facilitation or activation of ω-CgTxGVIA-sensitive Ca2+ channels which are silent before exposure to PDAc.

In contrast to the BIS-I-sensitive components, the BIS-I-resistant component of fEPSP potentiation, which is not dependent on Δ[Ca2+]pre (Fig. 6), was not accompanied by a reduction of the PPR (Figs 6 and 7). Therefore, the BIS-I-sensitive and BIS-I-resistant components of fEPSP potentiation employ distinct mechanisms. In summary, the PDAc-induced potentiation of the fEPSP appears to consist of at least three components: (1) a BIS-I-sensitive component that is accompanied by enhanced Δ[Ca2+]pre; (2) a BIS-I-sensitive component that is independent of Δ[Ca2+]pre; and (3) a BIS-I-resistant component without enhancement of Δ[Ca2+]pre.

The Δ[Ca2+]pre-dependent component (the first component)

Since neither the fEPSP nor Δ[Ca2+]pre was affected by 4α-phorbol, the BIS-I-sensitive component of PDAc-induced potentiation could be explained by activation of PKC. Reduction of Ca2+ sequestration by PKC is unlikely because PDAc neither decelerates the falling phase of Δ[Ca2+]pre nor increases the resting [Ca2+]pre. Rather, reduction of the falling phase-time constant could be attributed to Δ[Ca2+]pre-dependent enhancement of Ca2+ sequestration (Ohnuma et al. 1999). Since PDAc enhanced Δ[Ca2+]pre in each single mossy fibre terminal, the change would not have resulted from arousal of inactive terminals. PKC may possibly increase the action potential-induced Ca2+ influx into each nerve terminal by either upregulating Ca2+ channels (Shearman et al. 1989; Swartz, 1993; Stea et al. 1995) or by downregulating K+ channels (Doerner et al. 1988; Shearman et al. 1989; Hoffman & Johnston, 1998). This is consistent with the previous observation that the depolarization-evoked [Ca2+]i increment is enhanced by PKC activation in cerebral synaptosomes (Herrero et al. 1992).

The Δ[Ca2+]pre-insensitive and BIS-I-sensitive component (the second component)

Although PDAc increased Δ[Ca2+]pre, this could not explain the marked reduction of PPR (Fig. 4). In contrast, the BIS-I-resistant component of the PDAc effect was not accompanied by reduction of PPR (Fig. 6). As discussed above, these findings strongly suggest the existence of a BIS-I-sensitive component of the PDAc effect which cannot be explained by an increase in Δ[Ca2+]pre.

PKC increases the size of the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles in cultured hippocampal neuronal synapses (Stevens & Sullivan, 1998) as well as in chromaffin cells (Gillis et al. 1996). This is consistent with the observation that PKC increases the frequency of miniature synaptic events in hippocampal neurons in a Ca2+-independent manner (Capogna et al. 1995). In many synapses, the magnitude of the PPR is negatively correlated with the quantal content of the first response (Debanne et al. 1996; Schulz, 1997). The most plausible mechanism seems to be a depletion of the readily releasable pool for the second release or the refractoriness of release sites as a result of an increase in the fusion probability (Debanne et al. 1996; Dobrunz & Stevens, 1997; O'Donovan & Rinzel, 1997; Yawo, 1999; Dittman et al. 2000). In our preparation, the PPR decreased along with the development of PKC-dependent potentiation of the fEPSP slope (Fig. 7). It is assumed that the second pulse of a paired-pulse protocol admits the same amount of Ca2+ as the first, and produces the same elevation of [Ca2+]i as the first before (Fig. 1E) and after exposure to PDAc. Since PPR reduction was correlated with potentiation, PKC could at least upregulate the fusion probability of exocytosis by the first pulse. A plausible mechanism is an enhancement of the Ca2+ sensitivity of the exocytotic fusion probability by increasing the local [Ca2+]i in the vicinity of the Ca2+ sensor, by locating vesicles closer to the Ca2+ channel clusters, by upregulating the Ca2+ sensitivity of the Ca2+-sensor molecule, or by facilitating the linkage between the Ca2+ sensor and the fusion machinery.

The BIS-I-resistant component (the third component)

We could not exclude the possibility that the BIS-I-resistant component of the fEPSP potentiation is postsynaptic. However, this possibility appears unlikely because PDAc increased the mEPSC frequency in BIS-I without affecting the amplitude distribution in the CA3 pyramidal cell, and because the quantal size of the mossy fibre synapse was not increased during PDAc-induced potentiation of the EPSP (Yamamoto et al. 1987). This is in contrast to the observation that BIS-I prevents the phorbol ester-induced increase in mEPSC frequency in cultured hippocampal neuronal synapses (Capogna et al. 1999). Assuming that the BIS-I-resistant component is presynaptic, it is suggested to result from an increased size of the readily releasable pool of vesicles rather than from upregulation of the fusion probability (Gillis et al. 1996) because the fEPSP potentiation was not accompanied by a reduction of the PPR (Figs 6 and 7). It remains to be elucidated whether the BIS-I-resistant component is evoked by a BIS-I-insensitive PKC isoform or by non-PKC C1 domain-containing molecules, e.g. Munc13-1 which binds phorbol esters with an affinity similar to that of PKC and is distributed preferentially in mossy fibre terminals (Betz et al. 1998). We could not detect BIS-I-resistant fEPSP potentiation when the PDAc concentration was 0.5 μM. This would not necessarily mean that the non-PKC phorbol ester receptor is less sensitive to PDAc than the PKC receptor because responsiveness may be amplified by phosphorylation. However, this observation implies that a local accumulation of activators (e.g. diacylglycerol) would be a prerequisite for activation of non-PKC C1 domain-containing molecules.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr S. Sai for technical support and Dr T. Manabe and Mr B. Bell for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

References

- Acsády L, Kamondi A, Sik A, Freund T, Buzsáki G. GABAergic cells are the major postsynaptic targets of mossy fibers in the rat hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:3386–3403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03386.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine GJ, Charlton MP, Smith SJ. Calcium action in synaptic transmitter release. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1987;10:633–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.10.030187.003221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz A, Ashery U, Rickmann M, Augustin I, Neher E, Südhof TC, Rettig J, Brose N. Munc13–1 is a presynaptic phorbol ester receptor that enhances neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;21:123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M, Frankhauser C, Gagliardini V, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Excitatory synaptic transmission and its modulation by PKC is unchanged in the hippocampus of GAP-43-deficient mice. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:433–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Presynaptic enhancement of inhibitory synaptic transmission by protein kinases A and C in the rat hippocampus in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:1249–1260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01249.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo PE, Weisskopf MG, Nicoll RA. The role of Ca2+ channels in hippocampal mossy fiber synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1994;12:261–269. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Guérineau NC, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Paired-pulse facilitation and depression at unitary synapses in rat hippocampus: quantal fluctuation affects subsequent release. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;491:163–176. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney KR, Tank DW. A quantitative measurement of the dependence of short-term synaptic enhancement on presynaptic residual calcium. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:5885–5902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-05885.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Interplay between facilitation, depression, and residual calcium at three presynaptic terminals. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:1374–1385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01374.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrunz LE, Stevens CF. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron. 1997;18:995–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge FA, Jr, Rahamimoff R. Co-operative action of calcium ions in transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. The Journal of Physiology. 1967;193:419–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerner D, Pitler TA, Alger BE. Protein kinase C activators block specific calcium and potassium current components in isolated hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:4069–4078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04069.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis KD, Mößner R, Neher E. Protein kinase C enhances exocytosis from chromaffin cells by increasing the size of the readily releasable pool of secretory granules. Neuron. 1996;16:1209–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero I, MirasPortugal MT, Sánchez-Prieto J. Positive feedback of glutamate exocytosis by metabotropic presynaptic receptor stimulation. Nature. 1992;360:163–166. doi: 10.1038/360163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DA, Johnston D. Downregulation of transient K+ channels in dendrites of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons by activation of PKA and PKC. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:3521–3528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03521.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori T, Takai Y, Takahashi T. Presynaptic mechanism for phorbol ester-induced synaptic potentiation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:7262–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-Y, Li X-C, Kandel ER. cAMP contributes to mossy fiber LTP by initiating both a covalently mediated early phase and macromolecular synthesis-dependent late phase. Cell. 1994;79:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki S, Momiyama A, Uchitel OD, Takahashi T. Developmental changes in calcium channel types mediating central synaptic transmission. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:59–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00059.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D, Williams S, Jaffe D, Gray R. NMDA-receptor-independent long-term potentiation. Annual Review of Physiology. 1992;54:489–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.54.030192.002421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Ozawa S. Dual mechanism for presynaptic modulation by axonal metabotropic glutamate receptor at the mouse mossy fibre-CA3 synapse. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;518:497–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0497p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Yamamoto C. Phorbol ester and forskolin suppress the presynaptic inhibitory action of group-II metabotropic glutamate receptor at rat hippocampal mossy fiber synapse. Neuroscience. 1997;80:89–94. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Zucker RS. Residual Ca2+ and short-term synaptic plasticity. Nature. 1994;371:603–606. doi: 10.1038/371603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE. Relating hippocampal circuitry to function: recall of memory sequences by reciprocal dentate-CA3 interactions. Neuron. 1999;22:233–242. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewski H, Iannazzo L. Protein kinase C: a physiological mediator of enhanced transmitter output. Progress in Neurobiology. 1998;55:463–475. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Ayoub GS, Nicoll RA. Phorbol esters enhance transmitter release in rat hippocampal slices. Brain Research. 1987;403:198–203. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Madison DV, Nicoll RA. Potentiation of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus by phorbol esters. Nature. 1986;321:175–177. doi: 10.1038/321175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: new tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton AC. Regulation of protein kinase C. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 1997;9:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donovan MJ, Rinzel J. Synaptic depression: a dynamic regulation of synaptic communication with varied functional roles. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:431–433. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuma K, Kazawa T, Ogawa S, Suzuki N, Miwa A, Kijima H. Cooperative Ca2+ removal from presynaptic terminals of the spiny lobster neuromuscular junction. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:1819–1834. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77342-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman RS, Searl TJ, Hirsh JK, Silinsky EM. Opposing effects of phorbol esters on transmitter release and calcium currents at frog motor nerve endings. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;501:41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.041bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Stevens CF. Definition of the readily releasable pool of vesicles at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholfield CN, Smith AJ. A phorbol diester-induced enhancement of synaptic transmission in olfactory cortex. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1989;98:1344–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz PE. Long-term potentiation involves increases in the probability of neurotransmitter release. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:5888–5893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira R, Silberberg SD, Ginsburg S, Rahamimoff R. Activation of protein kinase C augments evoked transmitter release. Nature. 1987;325:58–60. doi: 10.1038/325058a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman MS, Sekiguchi K, Nishizuka Y. Modulation of ion channel activity: a key function of the protein kinase C enzyme family. Pharmacological Reviews. 1989;41:211–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha SR, Wu L-G, Saggau P. Presynaptic calcium dynamics and transmitter release evoked by single action potentials at mammalian central synapses. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:637–651. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(97)78702-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son H, Carpenter DO. Protein kinase C activation is necessary but not sufficient for induction of long-term potentiation at the synapse of mossy fiber-CA3 in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1996;72:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea A, Soong TW, Snutch TP. Determinants of PKC-dependent modulation of a family of neuronal calcium channels. Neuron. 1995;15:929–940. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Sullivan JM. Regulation of the readily releasable vesicle pool by protein kinase C. Neuron. 1998;21:885–893. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80603-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz KJ. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by protein kinase C in rat central and peripheral neurons: disruption of G protein-mediated inhibition. Neuron. 1993;11:305–320. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90186-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka C, Nishizuka Y. The protein kinase C family for neuronal signaling. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1994;17:551–567. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrian DM. Persistent enhancement of sustained calcium-dependent glutamate release by phorbol esters: requirement for localized calcium entry. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1995;67:172–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64010172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toullec D, Pianetti P, Coste H, Bellevergue P, GrandPerret T, Ajakane M, Baudet V, Boissin P, Boursier E, Loriolle F, Duhamel L, Charon D, Kirilovsky J. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:15771–15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Castillo PE, Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. Mediation of hippocampal mossy fiber long-term potentiation by cyclic AMP. Science. 1994;265:1878–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.7916482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-G, Saggau P. Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto C, Higashima M, Sawada S. Quantal analysis of potentiating action of phorbol ester on synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Neuroscience Research. 1987;5:28–38. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(87)90021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawo H. Protein kinase C potentiates transmitter release from the chick ciliary presynaptic terminal by increasing the exocytotic fusion probability. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;515:169–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.169ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalutsky RT, Nicoll RA. Comparison of two forms of long-term potentiation in single hippocampal neurons. Science. 1990;248:1619–1624. doi: 10.1126/science.2114039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Ruehr L, Dorman RV. Arachidonic acid and oleoylacetylglycerol induce a synergistic facilitation of Ca2+-dependent glutamate release from hippocampal mossy fiber nerve endings. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1996;66:177–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS. Exocytosis: a molecular and physiological perspective. Neuron. 1996;17:1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]