Obesity is a common problem for individuals with schizophrenia, a problem that has been exacerbated more recently with the increased use of second-generation antipsychotics, many of which are associated with the risk of weight gain and metabolic disturbance. Recently, a Cochrane review has been published examining pharmacological and nonpharmacological (diet/exercise) interventions for reducing and/or preventing weight gain in this population.

Objective

The objective of the review was to determine the effects of both pharmacological (excluding medication switching) and nonpharmacological strategies for reducing or preventing weight gain in individuals with schizophrenia.

Search Strategy

We searched key databases and the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's trials register and reference sections within relevant articles, hand searched key journals, and contacted the first author of each relevant study and other experts to collect further information.

Selection Criteria

All clinical randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing any pharmacological or nonpharmacological intervention for weight gain (eg, diet and exercise counseling including elements of cognitive and/or behavioral modification) with standard care or other treatments for individuals with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses were selected.

Data Collection and Analysis

Studies were reliably selected, quality assessed, and data extracted. Because weight is a continuous outcome measurement, weighted mean differences (WMD) of the change from baseline were calculated. Where heterogeneity existed (determined by a chi-square test), a random-effects model was used. The primary outcome measure was weight loss.

Main Results

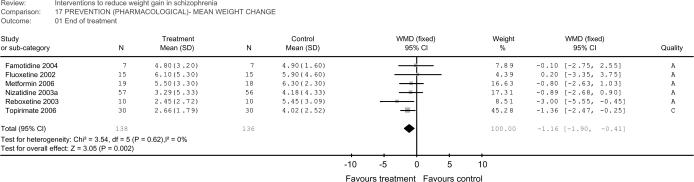

Twenty-three RCTs met the inclusion criteria for this review. Five trials assessed a cognitive/behavioral intervention and 18 assessed a pharmacological adjunct. In terms of prevention, there was a significant treatment effect in trials examining a pharmacological adjunct, demonstrating modest prevention of weight gain (6 RCTs, n = 274, WMD −1.16 kg, confidence interval [CI] −1.90 to −0.41; see Figure 1). Two cognitive/behavioral trails showed significant treatment effect (mean weight change) at end of treatment (2 RCTs, n = 104, WMD −3.38 kg, CI −4.81 to −1.96; see Figure 2). In terms of treatment, there was an overall treatment effect in trials examining a pharmacological adjunct, (9 RCTs, n = 273, WMD −2.97 kg, CI −4.48 to −1.46) although caution is required in interpreting this average outcome given significant heterogeneity (see Figure 3). Three cognitive/bahavioral trials showed significant treatment effect at end of treatment (3 RCTs, n = 129, WMD −1.69 kg, CI −2.77 to −0.61; see Figure 4).

Reviewers' Conclusions

Modest short-term weight loss can be achieved with selective pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. However, interpretation is limited by the small number of studies, small sample size, short study duration, and variability of the interventions themselves, their intensity, and duration. At this stage, no single pharmacological agent emerges as consistently superior in terms of weight loss efficacy. Of drugs currently in the market, reboxetine and topiramate were effective at weight prevention and topiramate (at 200 mg) was effective for established weight gain, although there was only a single study for each. There were mixed results with sibutramine, nizatidine, and amantadine and negative results for fluoxetine (treatment and prevention study) and famotadine and phenylpropinolamine. Nonpharmacological interventions incorporating dietary and physical activity modifications demonstrated promise in terms of preventing weight gain.

Implications for Practice

There is currently limited information in terms of RCTs to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of interventions to moderate weight gain. Existing data suggest that short-term modest weight loss is possible with nonpharmacological and selective pharmacological interventions. Given this modest weight loss, the first strategy in preventing or alleviating weight gain is to appraise metabolic risk when prescribing antipsychotic and other psychotropic medications, although priority should be given to achieving good control of the mental illness. Patients, family, and caregivers should be educated about metabolic risks and receive lifestyle advice regarding diet and physical activity.

Implications for Research

Further RCTs with larger samples and longer treatment duration are needed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions in preventing weight gain and effecting weight loss in schizophrenia patients treated with antipsychotic medications.

Fig. 1.

Pharmacological Interventions (Prevention).

Fig. 2.

Nonpharmacological Interventions (Prevention).

Fig. 3.

Pharmacological Interventions (Treatment).

Fig. 4.

Nonpharmacological Interventions (Treatment).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Ontario Mental Health Foundation for providing financial support for this review. We would also like to thank Clive Adams, Tessa Grant, and Gill Rizzello of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group for their help and support with this review. The full text of this review is available in the Cochrane Library. Disclosures: None.