Abstract

Abnormalities of the cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical (CSTC) and the limbic-cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical (LCSTC) circuits have been hypothesized in mood disorders. We performed principal components analysis (PCA) to identify latent volumetric systems on regional brain volumes and correlated these patterns with clinical characteristics, exploratory structural equation modeling (SEM) to test a priori hypotheses about the organization among the structures comprising the CSTC and LCSTC circuits and investigate differences among subjects with bipolar disorder (BD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and healthy controls (HC). Participants included 45 BD and 31 MDD patients, and 72 HC. Regional MR brain volumes were used to calculate patterns of volumetric covariance. The identified latent volumetric systems were related to the depression severity and the duration of illness. BD differed from HC on the estimated parameters describing the paths of cortico-striatal, thalamo-striatal and intrastriatal loops of CSTC circuit, and the paths between anterior and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and hippocampus to amygdala of LCSTC circuit. MDD differed from HC on the paths between putamen and thalamus, and PCC to hippocampus. This study provides evidence to suggest different organizational patterns among structures within the CSTC and LCSTC circuits for BD, MDD, and HC, which may point to structural abnormalities underlying mood disorders.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, Major depressive disorder, Brain MRI, Principal component analysis, Structural equation modeling, Neurocircuitry

1. Introduction

Despite relatively preserved global brain volumes, several studies suggest regional gray matter (GM) abnormalities in patients with bipolar disorder (BD). Using structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), regional gray matter volume deficits in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), particularly the subgenual PFC (SGPFC, BA 25) or more specifically the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sACC), have been reported in BD, unmedicated BD, familial BD and MDD patients. In addition, smaller amygdala volumes have been shown consistently in child and adolescent BD, though both larger and smaller amygdala volumes have been reported in adult BD compared to healthy subjects. Deficits in other connected structures such as the hippocampus, striatum and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) have also been reported, though the results are not conclusive).

Several models explaining emotional deficits in bipolar and depressive disorders have been hypothesized. The converging evidence from neuroimaging, neurophysiology, and social cognition studies supports the framework of dysfunctional networks within subcotical (striatial-thalamic)-prefrontal circuitry subserving cognition and neuropsychological process of emotional regulation in mood disorders. Specifically, diminished prefrontal modulation of subcortical (e.g. thalamus, basal ganglia) and medial temporal structures (e.g. ventral striatum, amygdala, hippocampus) within an anterior limbic network (hypoactive “top-down” dysfunction of prefrontal cortex and hyperactive “bottom-up” regulation of limbic system).

The cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical (CSTC) loop and the limbic-cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical (LCSTC) loop are the two major circuits involving the connections between PFC, striatum, and thalamus and the related parts of the limbic system (see. The cingulate cortex, a major part of the paralimbic system connecting the frontal lobe to the other limbic structures, can be divided into two major hetererogenous components in terms of cytoarchitecture and function, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC). Subgenual ACC serves as a pivotal structure directly linking the DLPFC and limbic system, and its structural change has been hypothesized as an important marker of mood disorders (see for review). Taken together, these findings suggest that mood disorders may be associated with a neuropathological process affecting neurocircuitry involving the connections between PFC, striatum, and thalamus within the CSTC circuit; and the related parts of the limbic system within the LCSTC circuit. However, to our knowledge, there is no published study illustrating the spatial relationships between latent volumetric measures within the CSTC and LCSTC circuits in mood disorders and their differences compared to healthy comparison subjects.

Previous research identified the latent structure within the regional brain volumes of healthy children and adults using exploratory factor analysis and structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM is a form of covariance analysis that allows testing of a priori hypotheses about the causality among variables. SEM assesses the statistical relationships among the latent variables, which represent theoretical constructs that underlie measured observations, the manifest variables. Here we present an analysis of anatomical MRI data, by using 1) correlational analysis of anatomically connected brain volumes, 2) principal component analysis (PCA) to identify the latent structures of volumetric covariance, 3) SEM to assess the a priori causal statistical relationships among brain regions comprising the latent variables, which may influence other measured brain volumes, within the CSTC and LCSTC circuits. The goals of this study were to test whether the structural networks within the CSTC and LCSTC circuits in BD and MDD are different from those of healthy controls (HC).

2. Materials and methods

This study is an analysis of previously published high-resolution 1.5 T (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) structural MRI data .

2.1. Participants

Participants included 72 HC, 45 BD and 31 MDD participants. All patients met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for BD or MDD, as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV;). The Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (25-item version; were used to rate the clinical symptoms and were administered within 1 week of the MRI study. Patients with comorbid psychiatric disorder except attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), current medical problems except hypertension, or alcohol or substance abuse within the 6 months preceding the study were excluded. Two BD were diagnosed ADHD previously, one MDD had history of panic attack, one MDD had alcohol abuse remitted more than 14 months, and one BD had poly-substance abuse remitted more than 6 months. Healthy controls were excluded if they had any DSM-IV axis I disorders, any first degree relatives with a history of psychiatric disorders, or any current serious medical problem.

All subjects received detailed information provided by the research psychiatrists on all aspects related to study, and signed informed consent for participation. This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

2.2. MRI Acquisition and Image Analysis

3D gradient echo imaging (Spoiled Gradient Recalled Acquisition, SPGR) was performed in the coronal plane (TR=25 ms, TE=5 ms, FOV=24 cm, slice thickness=1.5 mm, NEX=1, matrix size=256×192) covering the entire brain. The detailed anatomical measurements of brain regional volumes were performed as described previously. In short, volumetric measurements of prefrontal cortex (including DLPFC and SGPFC) and cingulate cortex (including anterior and posterior cingulate gyrus), thalamus, striatum (including caudate and putamen), hippocampus, amygdala and intra-cranial volume (ICV) were conducted using the semi-automated softwares. Specifically, Scion Image (Scion Corporation, INC. Frederick, MD) was used for tracing prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex, thalamus, striatum, hippocampus and amygdala). MEDx (http://medx.sensor.com) was used for tracing SGPFC. Brain regions were traced separately for left and right hemispheres, based on neuroanatomic atlases. Readers are encouraged to read the cited references for the detailed descriptions of neuroanatomical landmarks used on tracing the brain regions (dorsolateral PFC, cingulate cortex, thalamus, striatum, hippocampus, amygdala, and SGPFC).

Segmentation of gray matter, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were obtained from a histogram, as per method previously reported, with the software NIH or Scion Image. Brain volumes were calculated by multiplying the measured areas by the slice thickness (1.5 mm). The ICV were traced manually, excluding everything other than total cerebral gray and white matter, CSF, dura mater and sinuses. Temporal lobes, optic chiasma, pituitary, brainstem, and the cerebellum hemispheres were included. The inferior border did not extend below the base of the cerebellum. For the ICV measurements, the even slices were deleted, and the volumes were calculated by multiplying the final area by 0.3 cm. All volumes were reported in cubic centimeters.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS® v 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A multiple imputation procedure that implements a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method was used for the incomplete data of the SGPFC (8 of 72 HC and 2 of 45 BD participants) and DLPFC (2 of 72 HC participants) by assuming multivariate normality.

2.3.1. Partial Correlation

The bivariate Pearson’s product-moment partial correlation matrices were calculated separately within each hemisphere of the 10 brain regions after controlling for the effect of gender, age and ICV in BD, MDD and HC groups individually.

2.3.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA decomposes a correlation matrix with ones on the diagonal and minimizes the sum of the squared perpendicular distances to the component axis. To decompose the calculated partial correlation matrix, PCA was used to reduce the 20 brain volumes (10 regions on each hemisphere) by finding the eigenvectors (factors) and eigenvalues, which indicate the amount of variance accounted for by components. Only those factors whose eigenvalues were greater than 1 were retained. A scree plot, a plot of the eigenvalues associated with each factor, was used for the initial evaluation in determining the number of factor to retain. This would retain a maximal amount of the variance in the measured brain volumes. The prior communality estimate for each variable was set to one, and a varimax (orthogonal) rotation was applied for the initial PCA. A variable was considered clearly to load on a factor if the loading on the factor was 0.35 or greater. We obtained the component weighting scores and examined the inter-correlations between scores. Finally, a promax rotation was applied to the factor structure to assess whether an oblique rotation (which allows factors to be correlated) yielded a substantially different factor structure. Because the oblique rotation yielded the same factor pattern, however, only the varimax rotation is reported.

2.3.4. Correlational Analyses of factor scores

The estimated factor scores from the PCA analyses were regressed on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores, the number of lifetime manic and/or depressive episodes, and the estimated length of illness since first diagnosis (years) using Pearson correlation for the participants in BD and MDD groups separately.

2.3.3. Structural equation modeling (SEM) of Volumes within the CSTC and LCSTC circuits

We used SEM to test spatial relationships within the CSTC and LCSTC circuits. The causality here is a statistical one representing the linear influence of an independent variable on a dependent variable. The variables refer to partial correlation coefficients between regional brain volumes as described above. Fig. 1 shows the specific models we specified a priori within the CSTC (Fig. 1A) and LCSTC circuits (Fig. 1B). The latent (unobserved) variables are denoted by circles and manifest (measured) variables by rectangles following standard SEM notation practice. Dark thick arrows represent the hypothesized structural paths and the disturbance factors; while light thin arrows represent the manifest paths and their errors. Disturbance factors and errors of estimated residuals of manifest and measurement errors of latent variables are indicated by “D” and “e”, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Path diagrams depicting the SEM models tested to describe the CSTC circuit (Fig. 1A) and the LCSTC circuit (Fig. 1B). These path diagrams depict our a priori model of these neural circuits based on extant literature. The latent variables are denoted by circles and manifest variables by rectangles. Dark thick arrows represent the hypothesized structural paths and the disturbance factors; while light thin arrows represent the manifest paths and their errors. Disturbance factors and errors of estimated residuals of manifest and latent variables are indicated by “D” and “e”, respectively. DLPFC (dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex), caud (caudate), puta (putamen), SGPFC (subgenual prefrontal cortex), Hippo (hippocampus), acyg (anterior cingulate), pcyg (posterior cingulage) and amyg (amygdala).

The postulated CSTC circuit (Fig. 1A) is primarily based on prior animal studies. Although virtually the entire cortical gray matter projects to the basal ganglion, we elected to enter the DLPFC subregion, which has been shown to play an important role of the pathogenesis of mood disorders, as the only exogenous latent variable influencing volumes of the basal ganglia (BG) volumes. We entered putamen and caudate as latent variables representing shared variance between homologous structures in the left and right hemispheres. We included bidirectional projections from the thalamus to the putamen and caudate nuclei, because the globus pallidus is known in animals to project to the thalamus, which in turn project back to the striatum. The known feedback paths from the thamalus to the cortex (DLPFC) also are included in the model. In detail, we postulated that DLPFC input influences the volumes of both caudate nuclei and putamen, which in turn influence the volume of thalamus in the CSTC circuit (Fig. 1A). The feedback projection from thalamus to striatum was also included, represented by arrows originating from thalamus and pointing to caudate and putamen. Caudate nuclei and putamen were postulated to have reciprocal influence on each other’s volume. We did not include globus pallidus in the model due to the insufficient observations. Caudate nuclei, putamen, thalamus and DLPFC were entered as latent variables representing theoretical constructs that underlie specific manifestations of those constructs in the manifest variables (measured volume of each region of interest in left and right hemispheres).

Based on prior animal studies, SGPFC projects to amygdala, ACC, PCC, hippocampus, orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), and PFC in the LCSTC circuit. We did not include OFC in the model due to insufficient observations. We included the projections from PCC to hippocampus based on the route of cingulum fiber tracts, which connects the cingulate gyrus to the (para)hippocampal gyrus and entorhinal cortex.

In the LCSTC circuit (Fig. 1B), we proposed to investigate the spatial relationships between SGPFC (paralimbic system), cingulate cortex, amygdala-hippocampus (A-H) complex system, and “limbic” loop of the CSTC circuit. To simplify the model, the SGPFC was postulated to determine the DLPFC and ACC volumes. ACC was assumed to determine the volume of PCC, which in turn was assumed to affect the volumes of the hippocampi. In addition, the hippocampi were predicted to determine the volume of amygdala, which was hypothesized to determine the volume of SGPFC. The model would form a closed loop from SGPFC→ACC→ PCC→ A-H complex → SGPFC in the LCSTC circuits, which have been hypothesized as the major neuroanatomic circuitry involved in primary and secondary mood disorders. The DLPFC, SGPFC, anterior and posterior cingulate cortices, hippocampi and amygdalae were entered as latent variables.

The Pearson’s partial correlation coefficients from the correlation analysis described above were used for SEM. Data were analyzed in SAS using the PROC CALIS procedure. The analysis of covariance structure was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation. The ratio of (chi-square/degrees of freedom of chi-square) was used as a preliminary measure of overall fit, with values for an acceptable fit being < 2.5. Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) were used to determine the adequacy of overall model fit, and a model with CFI or GFI of 0.8 or more in the HC group, which had the largest sample, was considered acceptable. Parameter estimates for both manifest and latent variable equations were calculated and construed as indicating the strength of each individual path within the model. Non-standardized path parameter estimates with t-values >1.96 were considered significant at the two sided P<0.05 significance level. R2 values for latent variables, which provide a measure of the variance explained by each structural path, were also evaluated. In post hoc assessments of group difference in each structural path within the model, we considered absolute t-values > 1.96 as significant (P < 0.05 two sided testing).

3. Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects at the time of MR image acquisition are displayed in Table 1. Age was significantly different between groups (F(2, 147) = 7.88, P = 0.0006). The age of onset was significantly different between BD and MDD (F(1, 72) = 7.88, P = 0.0006, two subjects had missing data), but not the length of illness duration. The 25-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale was not different between BD and MDD. The means and standard deviations of ICV were HC = 1465 ±134 mm3, BD = 1494 ±146 mm3, MDD = 1413 ±109 mm3, and they were significantly different between groups (F(2,147) = 3.39, P = 0.037).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants.

| HC (n = 72) | BD (n = 45) | MDD (n = 31) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender number male (percent) | 40 (56) | 22 (49) | 7 (23) |

| Age (years) mean ± sd (range) | 30.0 ± 11.5 (11–50) | 29.6 ± 13.1 (10–61) | 39.2 ± 11.9 (18–58) |

| Handedness number left (percent) | 4 (6) | 5 (11) | 0 (0) |

| HAM-17 (mean ± sd)* | - | 7.6 ± 9.4 | 11.8 ± 9.1 |

| HAM-25 (mean ±sd)* | - | 9.3 ± 11.0 | 14.7 ± 10.9 |

| Length of illness (years; mean ±sd) | - | 11.6 ± 8.6 | 11.4 ± 10.6 |

| Age of onset (years, mean ± sd) | - | 16.9 ± 7.2 | 27.9 ± 11.6 |

HC healthy comparisons; BD bipolar disorder; MDD major depressive disorder

HAM-17, HAM-25: Hamilton Depression Rating Scales (17- and 25-item versions)

3.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

We extracted six eigenvectors (components) that accounted for larger than 75% cumulative variances in each group. Table 2 shows the six eigenvectors and factor loadings (multiplied by 100), which are the correlation coefficients between the regional brain volumes and factors. The squared factor loading is the percent of variance in that indicator variable explained by the factor. A negative loading indicates a negative relation of the regional brain volume to the factor. The first factor for the HC group (with proportions of variance of structural data explained in the following text) included caudate nuclei, putamen and thalamus and was interpreted as a BG system. This factor accounted for the largest share of the volumetric variance (27%). The second factor in HC included the cingulate gyri and hippocampi and was interpreted as a cingulate-hippocampus system (14%). The A-H complex system, including hippocampi and amygdalae, was the major constituent of the third factor (13%). The major component of the fourth factor in HC was SGPFC, which was interpreted as the paralimbic system (10%). The fifth factor included caudate nuclei, putamen, and anterior cingulate gyri, and was interpreted as a striato-limbic system (7%). The dorso-cortical system, which was mainly made up of DLPFC and hippocampi, was the sixth factor in HC. The order of the six factors in BD (with proportion of variance explained in parentheses) was BG system (22%), striato-limbic system (20%), cingulate-hippocampus system (12%), A-H complex system (9%), paralimbic system (8%) and dorso-cortical system (7%). The order of the six factors in MDD (with proportion of variance explained in parentheses) was BG system (26%), A-H complex system (17%), anterior-striato-limbic system (12%), dorso-cortical and A-H complex (amygdala) systems (10%), cingulate-hippocampus system (8%), and paralimbic system (6%).

Table 2.

The rotated six factor patterns of principle component analyses of left and right gray matter volumes among three groups. The factor (component) loadings were multiplied by 100 and rounded to the nearest integer, and bold for those equal to or greater than 35. The numbers below the group names indicate the order of factors in each group*.

| Factor Structure | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal ganglia factor |

Cingulate-hippocampus factor |

AH factor |

Para-limbic (SGPFC) factor |

Striato-limbic factor |

Dorso-cortical factor |

||||||||||||||

| HC (1) |

BD (1) |

MDD (1) |

HC (2)c |

BD (3) |

MDD (5) |

HC (3) |

BD (4) |

MDD (2) |

HC (4) |

BD (5) |

MDD (6) |

HC (5) |

BD (2) |

MDD (3) |

HC (6) |

BD (6) |

MDD (4) |

||

| DLPFC | left | 1 | 2 | 27 | −13 | −3 | 4 | 4 | −2 | −25 | −22 | −3 | −23 | 10 | −15 | −4 | 81 | 90 | 72 |

| right | 19 | 18 | 17 | 8 | 22 | 18 | −17 | −19 | −10 | −26 | −30 | −9 | 20 | −15 | 35 | 74 | 51 | 71 | |

| ACING | left | 40 | −1 | 14 | 40 | 32 | 18 | 6 | 15 | 63 | 10 | −6 | −6 | 58 | 67 | −15 | 37 | −20 | −18 |

| right | 8 | 0 | 19 | 74 | 53 | 81 | 14 | 5 | 22 | −16 | −9 | −7 | 41 | 54 | −17 | 30 | 27 | 0 | |

| PCING | left | 16 | 8 | −3 | 60 | 7 | 74 | 23 | 3 | 16 | 44 | 12 | 12 | −17 | 87 | 43 | 7 | −10 | 30 |

| right | −12 | 8 | 2 | 76 | 7 | 84 | −1 | 9 | 12 | −3 | −6 | −21 | −17 | 90 | 2 | −8 | −3 | 23 | |

| SGPFC | left | 3 | −19 | 9 | −1 | −16 | −10 | 14 | 18 | −8 | 92 | 85 | 90 | 0 | 6 | −13 | −16 | −6 | −20 |

| right | −16 | 10 | −6 | −6 | 6 | −7 | 14 | −14 | −4 | 88 | 90 | 92 | −12 | −8 | 2 | −28 | −2 | 2 | |

| Caudate | left | 37 | 69 | 9 | 4 | 18 | 4 | −9 | −14 | 24 | −6 | −4 | 2 | 89 | −42 | 83 | 7 | −32 | −5 |

| right | 70 | 59 | 44 | 7 | −3 | 0 | −5 | −5 | 6 | −6 | −25 | −15 | 86 | −18 | 82 | 8 | −60 | −1 | |

| Putamen | left | 89 | 88 | 80 | 18 | 9 | 5 | −4 | −4 | 25 | −3 | −3 | 16 | 50 | −17 | 20 | 25 | 1 | 2 |

| right | 89 | 84 | 80 | 15 | 14 | −9 | −1 | −3 | 20 | −10 | −23 | 14 | 48 | 15 | 31 | 22 | −10 | 15 | |

| right | 91 | 83 | 89 | 11 | −19 | 4 | −5 | 8 | −2 | −4 | 17 | −21 | 32 | 22 | −2 | 0 | 16 | −1 | |

| Thalamus | left | 90 | 81 | 91 | 13 | −3 | 21 | −14 | 0 | −8 | −7 | 4 | −2 | 45 | 36 | 9 | −12 | 20 | 8 |

| Hippocampus | left | 33 | 0 | 9 | 65 | 87 | 13 | −47 | 9 | 88 | −5 | −6 | 1 | 23 | 8 | 24 | −35 | −7 | 11 |

| right | 25 | 7 | 2 | 67 | 91 | 14 | −39 | −6 | 81 | −14 | −1 | −11 | 24 | 21 | 35 | −38 | 9 | 21 | |

| Amygdala | left | −2 | 1 | 22 | 6 | 11 | −24 | 82 | 91 | −32 | 20 | −2 | −16 | 1 | 10 | 44 | −13 | −17 | −63 |

| right | −3 | −6 | 6 | −9 | −4 | −17 | 89 | 94 | −36 | 17 | 6 | 2 | −10 | 11 | 14 | 10 | 8 | −73 | |

HC healthy comparisons; BD bipolar disorder; MDD major depressive disorder

The factor order from left to right (factor 1 to factor 6) was for HC,while the factor order for BD was basal ganglia system, striato-limbic system, cingulate-hippocampus system, AH complex system, paralimbic system and dorso-cortical system; and basal ganglia system, AH complex system, striato-limbic system, dorso-cortical systems, cingulate-hippocampus system, and paralimbic system for MDD, respectively.

3.2. Correlational Analyses of factor scores

In our sample of mood disorders patients, BD subjects with longer duration of illness also had greater lifetime numbers of manic episodes (r = 0.37, P = 0.02), but the number of lifetime depressive episodes in MDD did not correlate with the length of illness (P = 0.13). The correlations of the factor scores on the 25-item (n = 45) Hamilton Depression Rating Scale for the BD participants were inversely associated with the factor scores of the A-H complex system (r = −0.46, P = 0.01 for 25-item) and the dorso-cortical system (r = −0.47, P = 0.01 for 25-item). In the MDD subjects (n = 31), depression severity was significantly associated with the factor scores of cingulate-hippocampus complex system (r = −0.43, P = 0.02 for 25-item). The correlations between factor scores and length of illness in BD participants (42 out of 45 BD patcipants) were significant for the BG system (r = −0.51, P = 0.0007), paralimbic system (r = 0.37, P = 0.02), and dorso-cortical system (r = −0.56, P = 0.0002). The correlation between factor scores on the number of previous manic episodes was significant for the dorso-cortical system (r = −0.44, P = 0.006) in BD participants (39 out of 45 BD participants). However, the length of illness did not correlate significantly with the factor scores in MDD participants (all 31 MDD participants).

3.3. SEM of Volumes within CSTC and LCSTC circuits

Fig. 2A shows the SEM results and the estimates of the latent structural paths in HC for the CSTC circuit, after controlling for the effects of gender, age and total brain volume. Results for the BD and MDD are reported only in the text below. Fig. 2B shows the latent structural paths that showed statistically significant differences among the groups (see figure caption for details). The goodness of fit for the CSTC circuit were GFI = 0.93 and CFI = 0.98 in HC, GFI = 0.84 and CFI = 0.86 in BD, and GFI = 0.87 and CFI = 0.96 in MDD. The latent variables that had R2 values > 0.25 were R2putamen = 0.70 in HC, R2putamen = 0.68 and R2thalamus = 0.66 in BD, and R2putamen = 0.38 and R2thalamus = 0.50 in MDD.

Fig. 2.

Results of the SEM analysis of the CSTC circuit after controlling for the effects of gender, age and total brain volume. The significant group differences (t > 1.96) on estimated parameters are illustrated by * for HC vs BD, + for HC vs MDD, and # for BDD vs MDD. The non-standardized estimates of the latent structural paths in the HC group only (see texts for significant paths in BD and MDD), where the significant paths in HC are shown by dark thick arrows, and the non-significant paths are indicated by light thick arrows (Fig. 2A). The paths that showed statistically significant differences among groups with illustration of caudate (green), DLPFC (orange-yellow), putamen (blue), and thalamus (red) in coronal view of brain (Fig. 2B). Note the # in the bidirectional paths between thalamus to putamen is referring to unidirectional path from thalamus to putamen only.

For the CSTC circuit, the significant (t > 1.96) latent variable equations were the paths from the caudate nuclei to putamen in HC (path coefficient (θ) = 0.88, t = 28.39), BD (θ = 2.29, t = 7.43) and MDD (θ = 0.83, t = 79.64), which means if the volume of the caudate nuclei increases by one standard deviation (s.d.) then the volume of putamen would be expected to increase by 0.88 s.d. from the group mean of putamen volume in HC, 2.29 s.d. in BD, and 0.83 s.d. in MDD while holding all other relevant regional connections in the CSTC circuit constant. Additionally, the paths from thalamus to putamen were significant in HC (θ = 0.83, t = 5.87), in MDD (θ = 0.23, t = 2.58), and a trend in BD (θ = −0.86, t = −1.85). This means if the volume of thalamus increases by one s.d. from its group mean, then the volume of putamen would be expected to increase by 0.83 s.d. in HC, and 0.23 s.d. in MDD, but decrease by 0.86 s.d. in BD, while holding all other relevant regional connections in CSTC circuit constant. The path from putamen to thalamus was significant in BD (θ = 1.21, t = 4.13) and MDD (θ = 0.54, t = 4.69), the path from thalamus to caudate nuclei was significant in HC (θ = 0.16, t = 2.12) and BD (θ = 1.21, t = 4.41), and the path from caudate nuclei to thalamus was significant in HC (θ = 0.35, t = 14.05) and MDD (θ = 0.42, t = 10.86). In the BD subjects, the path from the putamen to caudate nuclei (θ = −0.86, t = 2.38), the path from thalamus to DLPFC (θ = 1.66, t = 2.51), and the paths from DLPFC to caudate nuclei (θ = −0.86, t = −4.28) and putamen (θ = 0.58, t = 3.64) were significant.

Next we compared the CSTC structural models of the three groups to identify the differences in the estimated path coefficients. The difference of path coefficients between groups suggests different structural interrelationships. A positive link can be interpreted as an “excitatory” effect, while a negative link for an “inhibitory” effect. The HC differed from the BD in the estimated latent volumetric relations in the paths between putamen and thalamus (putamen to thalamus, t = −3.48 (θ = −0.05 in HC, and 1.21 in BD); thalamus to putamen, t = 4.17 (θ = 0.83 in HC, and −0.56 in BD)). The HC also differed from the MDD with regards to these same paths (putamen to thalamus, t = −2.46 (θ = −0.05 in HC, and 0.54 in MDD); thalamus to putamen, t = 3.59 (θ = 0.83 in HC, and 0.23 in MDD)). The BD differed from the HC and MDD in the estimates of the latent structure path from DLPFC to caudate nuclei (θ = 0.002 in HC, −0.86 in BD, and 0.03 in MDD; BD-HC, t = −4.29; BD-MDD, t = −4.36), in the path from DLPFC to putamen (θ = 0.04 in HC, 0.58 in BD, and 0.005 in MDD; BDHC, t = 3.33; BD-MDD, t = 2.37), and in the path from thalamus to caudate nuclei (θ = 0.16 in HC, 1.21 in BD, and 0.02 in MDD; BD-HC, t = 3.69; BD-MDD, t = 4.26). In addition, the BD differed from the HC and MDD, i.e. BD has larger path coefficients than HC in the bidirectional paths between caudate and putamen (caudate to putamen (θ = 0.88 in HC, 2.29 in BD, and 0.82 in MDD; BD-HC, t = 4.57; BD-MDD, t = 4.76); putamen to caudate (θ = −0.02 in HC, 0.30 in BD, and −0.01 in MDD; BD-HC, t = 2.33; BD-MDD, t = 2.24)). Finally the BD differed from the HC in the path from thalamus to DLPFC (θ = −0.46 in HC, 1.66 in BD; BD-HC, t = 2.81), and differed from the MDD in the path from thalamus to putamen (θ = −0.56 in BD, 0.23 in MDD; BD-MDD, t = −2.51).

In summary (Fig. 2B), the BD patients differed from the other two groups mainly on the pathways projecting to the striatum, i.e. cortico-striatal, thalamo-striatal and intrastriatal (caudate-putamen) loops. Specifically, compared to HC, while holding all other relevant regional connections in CSTC circuit constant, BD had greater spatial interrelationships between caudate and putamen bidirectionally, and a larger volumetric effect from DLFPC to putamen; but a smaller effect from DLPFC to caudate. In addition, both BD and MDD patients differed from HC on the bidirectional spatial interrelationships between putamen and thalamus. Furthermore, HC differed from BD on the spatial volumetric difference in the projection of the thalamo-cortial loop.

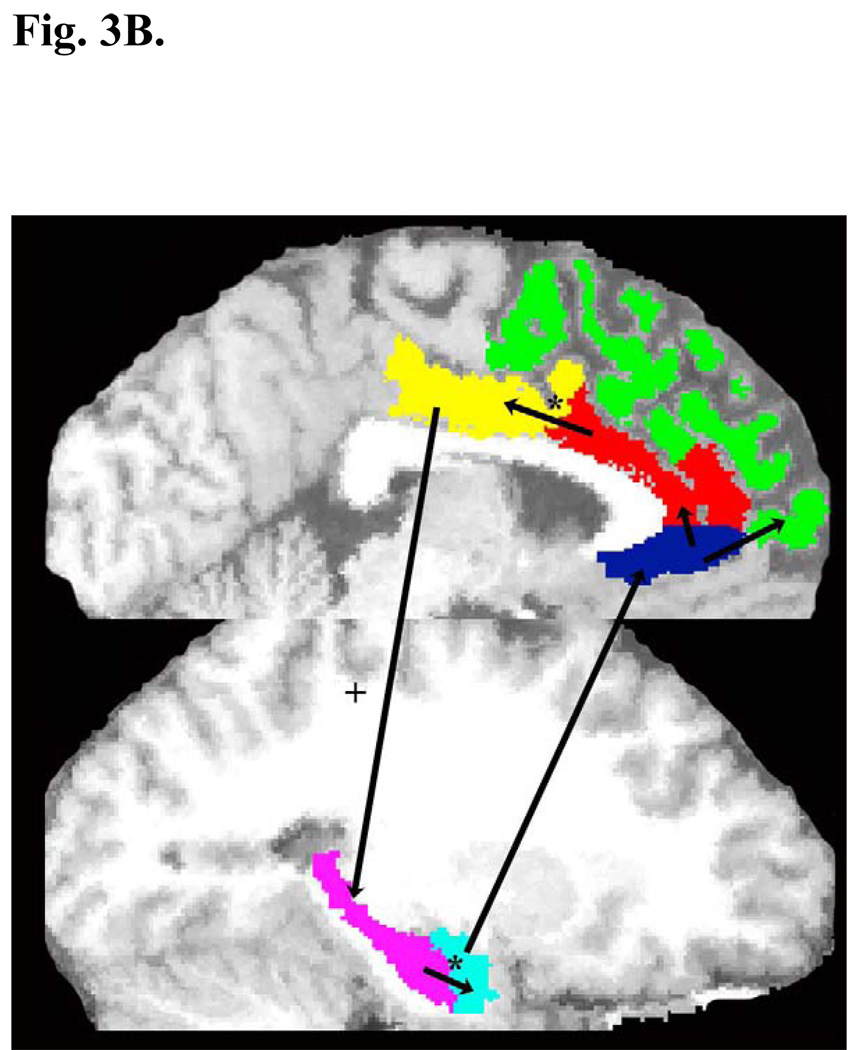

Fig. 3A shows the SEM results and the estimates of the latent structural paths in HC for the LCSTC circuits, after controlling for the effects of gender, age and total brain volume. Results for the BD and MDD are reported only in the text below. Fig. 3B shows the paths that showed statistically significant differences among the groups. The goodness of fit for the LCSTC circuit in each group were for HC GFI = 0.79 and CFI = 0.77, for BD GFI = 0.77 and CFI = 0.74, and for MDD GFI =0.77 and CFI = 0.92. The latent variables that had R2 values > 0.25 were R2PCC = 0.81 and R2SGPFC = 0.72 in BD.

Fig. 3.

Results of the SEM analysis of the LCSTC circuit after controlling for the effects of gender, age and total brain volume. The significant group differences (t > 1.96) on estimated parameters are illustrated by * for HC vs BD, + for HC vs MDD. The non-standardized estimates of the latent structural paths in HC group only (see texts for significant paths in BD and MDD), where the significant paths in HC are shown by dark thick arrows, and the non-significant paths are indicated by light thick arrows (Fig. 3A). The paths that showed statistically significant differences among groups with illustration of ACC (red), amygdala (light blue), DLPFC (green), hippocampus (pink), PCC (yellow), SGPFC (dark blue), and thalamus (red) in sagittal view of brain (Fig. 3B)

For the LCSTC circuits, the estimates of the latent variable equations were significant for the following paths. For HC, the path from SGPFC to DLPFC (θ = −0.01, t = −2.69), the path from hippocampi to amygdalae (θ = 0.27, t = 2.12), and the path from SGPFC to ACC (θ = 0.001, t = 2.03). For BD, the path from ACC to PCC (θ = 0.79, t = 5.19). For MDD, the path from PCC to hippocampus (θ = 0.39, t = 2.23) was significant.

In comparing the structural models of the LCSTC circuit across the three groups we found the following significant differences (Fig. 3B). HC differed from BD on the latent structural paths from ACC to PCC (θ = 0.05 in HC, 0.62 in BD; HCBD, t = −2.97), and the path from hippocampus to amygdala (θ = 0.27 in HC, −0.21 in BD; HC-BD, t = 2.19). MDD differed from HC on the latent structural path from PCC to hippocampus (θ = 0.01 in HC, 0.39 in MDD; HC-MDD, t = −2.22). These results mean that, while holding all other relevant regional connections in LCSTC circuit constant, BD adds more PCC volume than HC if the ACC volume increases; but reduces the amygdala volume if the hippocampus volume increases, which is in contrast to an increase of amygdala volume in HC. On the other hand, MDD adds more hippocampus volume if the PCC volume increases compared to HC (Fig. 3B).

4. Discussion

This study applied PCA and exploratory SEM to compare the structural correlations of anatomical brain measures within the CSTC and LCSTC circuits in HC and mood disorder patients. We statistically controlled for the potential confounding effects of gender, age, and ICV by analyzing the partial correlation matrices. PCA analysis of volumetric covariances demonstrated that the latent structures of regional brain volumes within the CSTC and LCSTC circuits can be organized into six major systems, i.e. BG, A-H complex, paralimbic, dorso-cortical, anterior-dorsal and posterior-ventral limbic systems, for HC and mood disorder participants. Depression severity was significantly associated with the factor scores of the A-H complex and dorso-cortical systems in BD, and with the cingulate-hippocampus system in MDD. The SEM results of a priori hypotheses of the structural connectivity within CSTC and LCSTC circuits revealed that the HC, BD and MDD groups had different latent spatial interrelationships in the pathways between striatum (especially putamen) and thalamus, and in the pathways between cingulate and A-H complex. In addition, BD displayed distinct anatomic relations of the connectivity between DLPFC and striatum, and intrastriatal loops, i.e. caudate nuclei and putamen, from those of HC and MDD groups.

4.1. Principal Component Analyses

The ventral component of ACC corresponds to the location of SGPFC in this study, while the three other components (anterior, dorsal and posterior) make up the defined ACC in our structural volume data. The factor loadings are the correlation coefficients between volumetric variables and the factors. Analogous to Pearson’s r, the squared factor loading is the percent of variance in that volumetric variable explained by the factor. The differences in the magnitudes of factor loading in BD and MDD, i.e. BD and MDD had lower factor loadings of the putamen, and BD had lower factor loadings of the ACC in the striato-limbic factor; the PCC in the cingulate-hipppocampus factor, the hippocampi in the A-H factor; and the amygdala in the dorso-cortical factor (Table 2), suggesting aberrant structural interrelationships between striatum and cortex, between ACC and PCC, and between A-H complex and frontal cortex in mood disorders. These findings are supported by the results of SEM analyses, which demonstrated the structural connectivity differences between the mood disorders and HC groups, i.e. on the paths between putamen and DLPFC, caudate and thalamus; ACC and PCC, hippocampus and amygdala in BD; and on the path from hippocampus to PCC in MDD. In addition, the high factor loading of amygdala for MDD in the dorso-cortical factor suggests MDD had larger structural correlation between DLPFC and amygdala than HC and BD.

The findings of a negative association between depression severity and the factor scores of the A-H complex system and dorso-cortical system in BD, and the cingulate-hippocampus system in MDD are supported by the roles of amygdala in emotional conflicts, and hippocampus in memory impairment that characterize mood disorders. The negative correlation of the illness duration of BD with the factor scores of the BG and dorso-cortical systems, but positive association with the factor scores of the paralimbic (SGPFC) system suggests the changes in the patterns of brain latent volumes that occur in chronic BD. These results suggest that a longer duration of illness in BD is associated with a greater volumetric change of paralimbic regions, but with a less volumetric change of BG and dorso-cortical regions. These results are consistent with the findings using the meta-analysis showing the reduction of paralimbic volume a characteristic of BD and the importance of illness of duration in determining the magnitude of effect sizes of brain structural changes in BD. Additionally, the significant associations between the factor scores of the dorso-cortical system and number of mania episodes, illness duration, and depression severity BD patients but not MDD patients may indicate a difference in the neural circuitry plasticity between BD and MDD.

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling and Neuroanatomic Model of Mood Disorders

Our SEM findings are consistent with the existing models and provide more insight to the latent brain structural brain changes in mood disorders. The hypothesized model of emotion regulation suggests that synergic dorsal cortical and limbic processes facilitate the adaptive generation and regulation of affect, with the dorsal system regulating affective states and the modification of consequent behaviors, and the ventral system modulating the automatic emotion regulation. Changes in the reciprocal relationships between the ventral limbic and dorsal cortical systems are critical in the physiological disturbances of mood disorders. These SEM results suggest BD have significant changes of structural interrelatinships within the cortico-striatal and thalamo-striatal loops of the CSTC circuitry (Fig. 2B), which directly subserve decision making and the selection of motivational drives, and are the critical projections between dorsal striatum and ventral striatum that directs the information flow between PFC and limbic systems. These latent structural changes might lead to hypoactive “top-down” dorsal cortical system, and thus weaken the inhibition from prefrontal cortex on the subcortical emotion processing systems in the cognitive control of emotional experience. These results support the fMRI studies of affect generation using mood provocation strategies, which demonstrated decreased neocortical neural activity and increased subcortical blood flow during negative mood induction in euthymic and depressed BD patients. The interrelationship between ACC and PCC in the neuropsychology of mood disorders has not been discussed extensively. Interestingly, our SEM findings of discordant ACC-PCC connection of LCSTC circuitry in BD (Fig. 3B) are consistent with the tract-specific analysis of our 3.0 T diffusion tensor imaging data, where we found unmedicated BD compared to HC had lower fractional anisotropy, a measure of white matter fiber directionality, in the dorsal cingulum where ACC and PCC divides (, manuscript in revision). ACC subserves executive functions related to inward-directed focus, while PCC has greater activity in outward-directed and social focus. The abnormal relationships between ACC and PCC, amygdala and hippocampus in LCSTC circuit would impair the inhibition from cingulate cortex on the subcortical emotion processing systems, and thus can influence the fate of motivational drives in the CSTC circuit. Our SEM may explain the fMRI findings of hyperactive amygdala but hypoactive medial prefrontal regions to negative facial expression in BD patients due to the failure of a cingulate modulatory role in the LCSTC circuit. In addition, these findings provide evidence of spatial abnormalities of motor (dorsolateral, via putamen and caudate body) and ‘associative’ (central, via caudate head) loops of the CSTC circuits in BD, indicating that the BD had deficits within the BG dopaminergic systems and DLPFC glutamatergic afferents of the striato-thalamic-prefrontal networks.

Turning attention to the MDD, our SEM finding of aberrent connectivity from putamen to thalamus in MDD provides evidence of deficits in thalamo-putamen interconnections in MDD. This result is supported by the positron emission tomography findings of lower putamen dopamine levels in depressed subjects with motor retardation. MDD patients, in contrast to BD patients who show increased prevalence of psychomotor symptoms, have been reported to have a more selective disturbance in episodic memory, i.e. dysfunction in mesial temporal lobe during episodes of depression. Our SEM analyses showed that the MDD had abnormal spatial patterns mainly in the limbic networks processing memory and emotion, but relative sparing of the networks processing motor function, indicating hyperactive “bottom-up” regulation in MDD. This is in accordance with the report showing that remission of depression is associated with concurrent inhibition of overactive paralimbic regions, mainly amygdala-hippocampus complex and normalization of hypofunctioning dorso-cortical sites. Moreover, the finding of an abnormal latent path from PCC to hippocampus suggests the possible failure of an A-H complex modulatory role in the LCSTC circuitry in MDD. Abnormalities of this neural loop may lead to impairment of primary encoding functions such as short-term and long-term recall and recognition. This deficit may result in a vicious cycle of depressive symptoms in MDD due to the failure of feedback control and input from hippocampus, i.e. negative memories and negative affect (Lawrence et al., 2004), and can influence the fate of motivational drive in the CSTC circuit.

In summary, our SEM findings of brain regional volumetric measures suggest hypoactive “top-down” dysfunction of the dorsal cortical system as the underlying cause of pathological emotional processing in BD, but hyperactive “bottom-up” regulation of the ventral limbic system as the likely main cause in MDD.

4.3. Limitations

We are aware this cohort might have atypical bipolar and depressive samples due to selection bias, inferred from the low comorbidity rate of BD subjects. The weaker factors resulting from our PCA will need independent validation due to the relatively small sample size. We did not assess the statistical power of the SEM models. However, it has been shown that statistical power is most affected by the degree of true factor mean differences and the size of the model. This suggests that if the hypothesis of factor mean differences was rejected under conditions of unequal sample size as in this study, then the null hypothesis probably is false. However, our SEM analysis has the same limitations as other summary statistics relative to multiple statistical testing. While correcting for multiple comparisons would help minimize the type I statistical errors, we did not do so because our analysis was specifically exploratory and our primary aim was to identify broad patterns in connectivity patterns not to test the significance of individual path coefficients.

We omitted from our analysis some key structures within the CSTC circuit, i.e. globus pallidus, due to the missing quantifications. Thus, we evaluated the CSTC circuit instead of the cortico-striatal-pallido-thalamocortial loops. In order to reduce the complexity and increase the stability of modeling we evaluated CSTC and LCSTC circuits in separate models. This simplification precluded the analysis of some potentially important spatial interrelationships in the circuitry, i.e. SGPFC-striatum and ACC-striatum loops. Larger sample size would be needed for modeling the CSTC and LCSTC circuits simultaneously. In addition, we postulated that the PCC has a direct connection to the hippocampus, but not the amygdala, and that the amygdala has a connection to the SGPFC, but not the hippocampus. The impact of omitting these paths on the SEM results would be minimal as their connectivities are weaker as compared to the proposed paths in this study. We explored SEM models that included the additional paths within the LCSTC circuit (not shown), and the goodness of fit and the path significances were similar to those for the reported model.

4.4. Conclusion

Our findings suggest that patients with BD have extensive abnormalities in the spatial connections involving the cortico-striatal, striatal-thalamic, thalamo-cortical and amygdala-SGPFC-DLPFC pathways; while patients with MDD have abnormalities within the striatal-thalamic and cingulate-hippocampus-SGPFC pathways of the CSTC and LCSTC circuits. Taken together, these result suggest that mood disorders are associated with a neuropathological process affecting the anatomical circuits involving the prefrontal lobe and (para)limbic system. These abnormalities could underlie the exaggerated affective responses (mania/depression), mood lability (susceptibility to prominent mood swings), and disinhibition (impulsivity and distractibility) that characterize these mood disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is partly supported by MH 68766, MH 068662, RR 20571, UTHSCSA GCRC (M01-RR-01346), NARSAD, AFSP, Dana Foundation, Veterans Administration (Merit Review), and the Krus Endowed Chair in Psychiatry (UTHSCSA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Alexander GE, Crutcher MD. Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends in Neurosciences. 1990;13:266–271. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90107-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler LL, Bartzokis G, Grieder T, Curran J, Jimenez T, Leight K, Wilkins J, Gerner R, Mintz J. An MRI study of temporal lobe structures in men with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:147–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00836-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone D, Cavanagh J, Gerber D, Lawrie SM, Ebmeier KP, McIntosh AM. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195:194–201. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden CE, Glahn DC, Monkul ES, Barrett J, Najt P, Kaur S, Sanches M, Villarreal V, Bowden C, Soares JC. Sources of declarative memory impairment in bipolar disorder: mnemonic processes and clinical features. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden CE, Thompson PM, Dalwani M, Hayashi KM, Lee AD, Nicoletti M, Trakhtenbroit M, Glahn DC, Brambilla P, Sassi RB, Mallinger AG, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Soares JC. Greater cortical gray matter density in lithium-treated patients with bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech P, Bolwig TG, Kramp P, Rafaelsen OJ. The Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale and the Hamilton Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1979;59:420–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1979.tb04484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer JL, Kuchibhatla M, Payne ME, Moo-Young M, Cassidy F, Macfall J, Krishnan KR. Hippocampal volume measurement in older adults with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;12:613–620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg HP. Dimensions in the development of bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:104–106. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg HP, Kaufman J, Martin A, Whiteman R, Zhang JH, Gore JC, Charney DS, Krystal JH, Peterson BS. Amygdala and hippocampal volumes in adolescents and adults with bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:1201–1208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botteron KN, Raichle ME, Drevets WC, Heath AC, Todd RD. Volumetric reduction in left subgenual prefrontal cortex in early onset depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:342–344. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla P, Harenski K, Nicoletti M, Sassi RB, Mallinger AG, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Keshavan MS, Soares JC. MRI investigation of temporal lobe structures in bipolar patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2003;37:287–295. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla P, Harenski K, Nicoletti MA, Mallinger AG, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Keshavan MS, Soares JC. Anatomical MRI study of basal ganglia in bipolar disorder patients. Psychiatry Research. 2001;106:65–80. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(01)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano SC, Sassi R, Brambilla P, Harenski K, Nicoletti M, Mallinger AG, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Keshavan MS, Soares JC. MRI study of thalamic volumes in bipolar and unipolar patients and healthy individuals. Psychiatry Research. 2001;108:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(01)00123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Price JL. Architectonic subdivision of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex in the macaque monkey. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1994;346:366–402. doi: 10.1002/cne.903460305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Price JL. Limbic connections of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex in macaque monkeys. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1995;363:615–641. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavada C, Company T, Tejedor J, Cruz-Rizzolo RJ, Reinoso-Suarez F. The anatomical connections of the macaque monkey orbitofrontal cortex. A review. Cerebral Cortex. 2000;10:220–242. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K, Karchemskiy A, Barnea-Goraly N, Garrett A, Simeonova DI, Reiss A. Reduced amygdalar gray matter volume in familial pediatric bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:565–573. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000159948.75136.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BK, Sassi R, Axelson D, Hatch JP, Sanches M, Nicoletti M, Brambilla P, Keshavan MS, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Soares JC. Cross-sectional study of abnormal amygdala development in adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Lennox B, Jacob R, Calder A, Lupson V, Bisbrown-Chippendale R, Suckling J, Bullmore E. Explicit and implicit facial affect recognition in manic and depressed States of bipolar disorder: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colibazzi T, Zhu H, Bansal R, Schultz RT, Wang Z, Peterson BS. Latent volumetric structure of the human brain: Exploratory factor analysis and structural equation modeling of gray matter volumes in healthy children and adults. Human Brain Mapping. 2007 doi: 10.1002/hbm.20466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, Zimmerman ME, Mills NP, Getz GE, Strakowski SM. Magnetic resonance imaging analysis of amygdala and other subcortical brain regions in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2004;6:43–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-5618.2003.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC. Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies of depression: implications for the cognitive-emotional features of mood disorders. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2001;11:240–249. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Ongur D, Price JL. Neuroimaging abnormalities in the subgenual prefrontal cortex: implications for the pathophysiology of familial mood disorders. Molecular Psychiatry. 1998;3:220–226. 190–221. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Price JL, Simpson JR, Jr, Todd RD, Reich T, Vannier M, Raichle ME. Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature. 1997;386:824–827. doi: 10.1038/386824a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison-Wright I, Bullmore E. Anatomy of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;117:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Egner T, Peraza DM, Kandel ER, Hirsch J. Resolving emotional conflict: a role for the rostral anterior cingulate cortex in modulating activity in the amygdala. Neuron. 2006;51:871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis KN, Giannakopoulos P, Kovari E, Bouras C. Assessing the role of cingulate cortex in bipolar disorder: Neuropathological, structural and functional imaging data. Brain Research Reviews. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey BN, Andreazza AC, Nery FG, Martins MR, Quevedo J, Soares JC, Kapczinski F. The role of hippocampus in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2007;18:419–430. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282df3cde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert AR, Rosenberg DR, Harenski K, Spencer S, Sweeney JA, Keshavan MS. Thalamic volumes in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:618–624. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Cahill CM, Malhi GS. The cognitive and neurophysiological basis of emotion dysregulation in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;103:29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Fudge JL, McFarland NR. Striatonigrostriatal pathways in primates form an ascending spiral from the shell to the dorsolateral striatum. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:2369–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02369.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L. A Step by Step Approach to Using the SAS System for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Haznedar MM, Roversi F, Pallanti S, Baldini-Rossi N, Schnur DB, Licalzi EM, Tang C, Hof PR, Hollander E, Buchsbaum MS. Fronto-thalamo-striatal gray and white matter volumes and anisotropy of their connections in bipolar spectrum illnesses. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L. A new anatomical framework for neuropsychiatric disorders and drug abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1726–1739. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayasu Y, Shenton ME, Salisbury DF, Kwon JS, Wible CG, Fischer IA, Yurgelun-Todd D, Zarate C, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, McCarley RW. Subgenual cingulate cortex volume in first-episode psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1091–1093. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit index in covariance structural analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J, Lyoo IK, Dager SR, Friedman SD, Oh JS, Lee JY, Kim SJ, Dunner DL, Renshaw PF. Basal ganglia shape alterations in bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:276–285. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GD, Duncan JS. MRI anatomy: a new angle on the brain. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen-Berg H, Gutman DA, Behrens TE, Matthews PM, Rushworth MF, Katz E, Lozano AM, Mayberg HS. Anatomical Connectivity of the Subgenual Cingulate Region Targeted with Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Cerebral Cortex. 2007 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Raye CL, Mitchell KJ, Touryan SR, Greene EJ, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Dissociating medial frontal and posterior cingulate activity during self-reflection. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2006;1:56–64. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D. Statistical power in structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1995. pp. 100–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D, George R. A study of the power associated with testing factor mean differences under violations of factorial invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1995;2:101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Sassi RB, Axelson D, Nicoletti M, Brambilla P, Monkul ES, Hatch JP, Keshavan MS, Ryan N, Birmaher B, Soares JC. Cingulate cortex anatomical abnormalities in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1637–1643. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Anderson S, Beckwith C, Nash K, Pettegrew JW, Krishnan KR. A comparison of stereology and segmentation techniques for volumetric measurements of lateral ventricles in magnetic resonance imaging. Psychiatry Research. 1995;61:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0925-4927(95)02446-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Bagwell WW, Haas GL, Sweeney JA, Schooler NR, Pettegrew JW. Changes in caudate volume with neuroleptic treatment. Lancet. 1994;344:1434. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90599-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Dick E, Mankowski I, Harenski K, Montrose DM, Diwadkar V, DeBellis M. Decreased left amygdala and hippocampal volumes in young offspring at risk for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2002;58:173–183. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger S, Seminowicz D, Goldapple K, Kennedy SH, Mayberg HS. State and trait influences on mood regulation in bipolar disorder: blood flow differences with an acute mood challenge. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:1274–1283. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence NS, Williams AM, Surguladze S, Giampietro V, Brammer MJ, Andrew C, Frangou S, Ecker C, Phillips ML. Subcortical and ventral prefrontal cortical neural responses to facial expressions distinguish patients with bipolar disorder and major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55:578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Larson MP, DelBello MP, Zimmerman ME, Schwiers ML, Strakowski SM. Regional prefrontal gray and white matter abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyoo IK, Sung YH, Dager SR, Friedman SD, Lee JY, Kim SJ, Kim N, Dunner DL, Renshaw PF. Regional cerebral cortical thinning in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2006;8:65–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS. Limbic-cortical dysregulation: a proposed model of depression. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1997;9:471–481. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Liotti M, Brannan SK, McGinnis S, Mahurin RK, Jerabek PA, Silva JA, Tekell JL, Martin CC, Lancaster JL, Fox PT. Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:675–682. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHaffie JG, Stanford TR, Stein BE, Coizet V, Redgrave P. Subcortical loops through the basal ganglia. Trends in Neurosciences. 2005;28:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JH, McNeely HE, Sagrati S, Boovariwala A, Martin K, Verhoeff NP, Wilson AA, Houle S. Elevated putamen D(2) receptor binding potential in major depression with motor retardation: an [11C]raclopride positron emission tomography study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1594–1602. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton FA, Strick PL. Basal-ganglia 'projections' to the prefrontal cortex of the primate. Cerebral Cortex. 2002;12:926–935. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.9.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PB, Wilhelm K, Parker G, Austin MP, Rutgers P, Malhi GS. The clinical features of bipolar depression: a comparison with matched major depressive disorder patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62:212–216. quiz 217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najt P, Nicoletti M, Chen HH, Hatch JP, Caetano SC, Sassi RB, Axelson D, Brambilla P, Keshavan MS, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Soares JC. Anatomical measurements of the orbitofrontal cortex in child and adolescent patients with bipolar disorder. Neuroscience Letters. 2007;413:183–186. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlson GD, Barta PE, Powers RE, Menon RR, Richards SS, Aylward EH, Federman EB, Chase GA, Petty RG, Tien AY. Ziskind-Somerfeld Research Award 1996. Medial and superior temporal gyral volumes and cerebral asymmetry in schizophrenia versus bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;41:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception I: The neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:504–514. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Lindenberger U, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Head D, Williamson A, Dahle C, Gerstorf D, Acker JD. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: general trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:1676–1689. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi RB, Brambilla P, Hatch JP, Nicoletti MA, Mallinger AG, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Keshavan MS, Soares JC. Reduced left anterior cingulate volumes in untreated bipolar patients. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, Solms M, Ramesar R. Neuropsychological dysfunction in bipolar affective disorder: a critical opinion. Bipolar Disorders. 2005;7:216–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Deutch AY, Roth RH, Bunney BS. Topographical organization of the efferent projections of the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: an anterograde tract-tracing study with Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1989;290:213–242. doi: 10.1002/cne.902900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline YI. 3D MRI studies of neuroanatomic changes in unipolar major depression: the role of stress and medical comorbidity. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:791–800. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline YI. Neuroimaging studies of mood disorder effects on the brain. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:338–352. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, Raju DV, Pare JF, Sidibe M. The thalamostriatal system: a highly specific network of the basal ganglia circuitry. Trends in Neurosciences. 2004;27:520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares JC, Kochunov P, Monkul ES, Nicoletti MA, Brambilla P, Sassi RB, Mallinger AG, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Lancaster J, Fox P. Structural brain changes in bipolar disorder using deformation field morphometry. Neuroreport. 2005;16:541–544. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200504250-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares JC, Mann JJ. The anatomy of mood disorders--review of structural neuroimaging studies. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;41:86–106. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, Delbello MP, Adler CM. The functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder: a review of neuroimaging findings. Molecular Psychiatry. 2005;10:105–116. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Sax KW, Zimmerman ME, Shear PK, Hawkins JM, Larson ER. Brain magnetic resonance imaging of structural abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:254–260. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swayze VW, 2nd, Andreasen NC, Alliger RJ, Yuh WT, Ehrhardt JC. Subcortical and temporal structures in affective disorder and schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Biological Psychiatry. 1992;31:221–240. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:674–684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Tavares JV, Clark L, Furey ML, Williams GB, Sahakian BJ, Drevets WC. Neural basis of abnormal response to negative feedback in unmedicated mood disorders. Neuroimage. 2008;42:1118–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA, Finch DM, Olson CR. Functional heterogeneity in cingulate cortex: the anterior executive and posterior evaluative regions. Cerebral Cortex. 1992;2:435–443. doi: 10.1093/cercor/2.6.435-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorn P, Vanderschuren LJ, Groenewegen HJ, Robbins TW, Pennartz CM. Putting a spin on the dorsal-ventral divide of the striatum. Trends in Neurosciences. 2004;27:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh PH, Monkul-Nery S, Nicoletti MA, Nery FG, Zunta-Soares GB, Li J, Lancaster J, Soares JC. Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS) of Diffusion Tensor Imaging Data in Bipolar Disorder: Abnormalities of the Neurocircuitry. Toronto, Canada: International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 16th Scientific Meeting and Exhibition; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yuh WTC, Tali ET, Afifi AK, Sahinoglu K, Gai F, Bergman RA. MRI of head and neck anatomy. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994. [Google Scholar]