Abstract

Adoptive cell therapy with engineered T cells to improve natural immune response and antitumor functions has shown promise for treating cancer. However, the requirement for extensive ex vivo manipulation of T cells and the immunosuppressive effects of the tumor microenvironment limit this therapeutic modality. In the present study, we investigated the possibility to circumvent these limitations by engineering Stat3-deficient CD8+ T cells or by targeting Stat3 in the tumor microenvironment. We show that ablating Stat3 in CD8+ T cells prior to their transfer allows their efficient tumor infiltration and robust proliferation, resulting in increased tumor antigen-specific T cell activity and tumor growth inhibition. For potential clinical translation, we combined adoptive T cell therapy with an FDA-approved tyrosine kinase inhibitor, sunitinib, in renal cell carcinoma and melanoma tumor models. Sunitinib inhibited Stat3 in dendritic cells and T cells, reduced conversion of transferred Foxp3− T cells to tumor-associated T regulatory cells while increasing transferred CD8+ T cell infiltration and activation at the tumor site, leading to inhibition of primary tumor growth. These data demonstrate that adoptively transferred T cells can be expanded and activated in vivo either by engineering Stat3 silenced T cells or by targeting Stat3 systemically with small-molecule inhibitors.

Keywords: Stat3, T cells, adoptive transfer

INTRODUTION

Adoptive T cell therapy has shown promise for cancer therapy. Despite several recent advances, however, this treatment modality still faces a number challenges. One major challenge is that ex vivo expanded, antigen-specific T cells must proliferate, and preserve their effector functions and homing abilities over many weeks prior to infusion into patients, and then remain active after infusion in order to generate therapeutic effects (1, 2). Even when T cells are engineered and expanded for optimal tumor specificity and homing, the tumor microenvironment plays a major role in determining the success of immune-based therapy (3, 4). T lymphocyte populations within a tumor are heterogeneous, and infiltrating T cells have been associated with either improved or poor prognosis, depending on the type of T cell population (5, 6). Anti-tumor immune responses driven by effector T cells are limited by their susceptibility to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. The immunosuppressive effects are largely generated by cytokines and other tumor-produced factors, and by immune cells within the tumor microenvironment, such as myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) (7, 8). In addition, tumors can also express ligands, such as PD-L1, for turning off T cell antitumor effects (9).

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) acts as a point of convergence for several oncogenic signaling pathways, and is persistently activated in numerous tumors as well as in various immune cells within the tumor microenvironment (4, 10, 11). By virtue of its ability to upregulate expression of multiple factors that are upstream of Stat3, Stat3 activity can be propagated from tumor cells to diverse immune cells and vice versa, creating a crosstalk between cancer cells and surrounding stroma (4, 11). Moreover, Stat3-regulated factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and interleukin-23 (IL-23), among many others, promote tumor growth, angiogenesis and invasion (12–14). Stat3 signaling in both tumor cells and the tumor-associated immune cells plays an important role in promoting MDSC and Tregs (4, 15). In addition to promoting expression of immune suppressive molecules, Stat3 negatively regulates expression of immunostimulatory factors in both tumor cells and myeloid cells, resulting in a microenvironment strongly reducing immune recognition and response against tumors. Our previous studies indicate that blocking Stat3 signaling within the myeloid compartment enhances anti-tumor immune responses through interruption of the immunosuppressive network that inhibits normal function of both adaptive and innate immunity (16, 17). However, whether Stat3 signaling within CD8+ T cells is inhibitory to their anti-tumor effector functions remains unknown.

Sunitinib is an orally bioavailable oxindole small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)-1, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFR)-α, PDGFR-β and stem cell factor (18). Growth inhibition of multiple implanted solid tumors and eradication of larger, established tumors has been demonstrated in mouse xenograft models (19). Sunitinib therapy has demonstrated improved survival for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), and has become a front-line therapy for the disease (20). Sunitinib has also shown antitumor efficacy in multiple tumor types, indicating its multifaceted role in tumor growth inhibition (21). Recent studies have evaluated the role of sunitinib in modulating immune cells within the tumor microenvironment. Sunitinib has been shown to inhibit MDSC and Tregs in RCC patients (22, 23) and in mouse tumor models (24, 25). In addition, sunitinib can inhibit Stat3, leading to increased tumor apoptosis and decreased MDSC and Tregs in tumor-bearing mice (26).

Although Stat3’s role in both tumor cells, myeloid cells and Tregs in promoting the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment is well known, whether Stat3 signaling within CD8+ T cells affects T cell effector functions remain unclear. Therefore, we investigated the feasibility of targeting Stat3 in T cells promote transferred T cell tumor infiltration and expansion, and stimulation of T cell functions. Our results showed that these criteria can be met by either transferring Stat3-deficient CD8+ naïve T cells or by systemic sunitinib treatment to inhibit Stat3 signaling in conjunction with T cell transfer. These findings serve as a platform to genetically modify T cells to block Stat3 prior to transfer and/or to use effective direct or indirect Stat3 inhibitors to modulate the tumor microenvironment to improve adoptive T cell immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The B16 cell line was obtained originally from American Type Culture Collection. B16OVA cell line was kindly provided by Dr J. Mule from Moffitt Cancer Center (Tampa, FL). The Renca murine cell line was obtainedfrom Dr. A. Chang (University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, MI). These cell lines were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 5–10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin. Intracellular staining and flow cytometry of B16 cells were used to check expression of melanoma-specific HMB-45 antigen (data not shown). The expression of exogenous OVA antigen and B16 cell-specific endogenous TRP2 and p15E antigens was confirmed by ELISPOT performed within the last six months. The ability of these cells to form melanoma in C57BL/6 mice and to elicit OVA-specific response was monitored.

Animals

Stat3flox mice were provided by S. Akira (Laboratory of Host Defense, World Premiere International Immunology Frontier Research Center and Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University, Suita, Osaka, Japan) and K. Takeda (Department of Molecular Genetics, Medical Institute of Bioregulation, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan). C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). CD4Cre mice were purchased from Taconic, OVA TCR (OT-I), GFP positive, Rag1−/− and Rag2−/− transgenic mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Foxp3-GFP knock in mice were provided by D. Zeng (Departments of Diabetes Research & Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte CA). Mouse care and experimental procedures were performed under pathogen-free conditions in accordance with established institutional guidance and approved protocols from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Beckman Research Institute at City of Hope National Medical Center.

In vivo experiments and T cells adoptive transfer

B16 or B16OVA melanoma cells were injected subcutaneously into Rag1−/− or wild type mice at 1 × 105 cells. Renca tumor cells (2.5 × 106) were injected subcutaneously into Rag2−/− mice. Mice received adoptive transfer of 8–10 × 106 CD8+ T cells 1 day prior or at day 5–6 after tumor challenge. CD8+ cells were isolated from spleens and lymph nodes of donor animals by magnetic beads enrichment using positive selection EasySep kits (StemCell Technologies) or MACS cell separation system (Miltenyi Biotec). T cells were transferred by retro orbital injection. In experiments for in vivo Tregs conversion Rag1−/− received 1 × 106 CD4+ GFP− cells isolated from FoxP3-GFP knock-in C57BL/6 mice.

Sunitinib treatment

Sunitinib (SU11248; Sutent) was purchased from LC Laboratories or supplied by Pfizer Inc.. Tumor bearing mice received sunitinib treatment at dose 30 to 40mg/kg dissolved in 0.5% solution of carboxymethyl cellulose, administered orally daily for up to 14 days.

Flow cytometry

Cell suspensions from lymph nodes and tumor tissues were prepared as described previously (3) and stained with different combinations of fluorochrome-coupled antibodies to CD4, CD8, CD25, FoxP3, CD11c, CD11b, Gr1, phospho-Tyr705-Stat3, (BD Biosciences). Fluorescence data were collected on Accuri C6 (Accuri Cytometers) or CyAn (Dako Cytomation, Inc), and analyzed using Cflow software (Accuri Cytometers) or FlowJo software (Tree Star). For in vitro and in vivo experiments for Tregs conversion CD4+ GFP cells were sorted using MoFlo™ MLS cell sorter (Dako Cytomation, Inc).

Immunofluorescence

Tumor tissue sections were fixated in 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in methanol. After blocking in PBS containing 10% goat serum and 2.5% mouse serum, slides were incubated overnight with antibodies: rat anti mouse CD4 (1:20, BD Biosciences) and rabbit anti FoxP3 (1:500; Abcam). Next day the slides were washed and secondary antibodies were applied for 1h (goat anti-rabbit, Alexa Fluor 488 labeled and goat anti-rat, Alexa Fluor 555, both 1:200, Molecular Probes).

Intravital multiphoton microscopy (IVMPM)

Rag1−/− mice bearing B16OVA tumors received adoptive transfer of ova specific Stat3+/+ and Stat3−/− CD8+ cells (1.5 × 107 of each) previously labeled with cell trackers (CMAC or OrangeCMTMR reagents (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturers instructions. After 48 or 72 hours mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane/oxygen followed by i.v. injection (via retro-orbital route) with dextran-fluoresceine (100 μg; Molecular Probes). Fifteen minutes later, tumor tissues of mice were surgically exposed for IVMPM and imaged with an Ultima Multiphoton Microscopy System (Prairie Technologies). For recording fluoresceine and rhodamine emission signals, λ = 860 nm excitation wavelength was used. Extracellular matrix (ECM) was recorded given by second harmonic generation (2HG) using λexcit.=890 nm. Band-pass filters optimized for and rhodamine (BP λ = 570 – 620 nm), coumarin and 2HG (BP λ = 460/50 nm) were used for detection.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay

To detect IFNλ or Granzyme B ELISPOT assay was performed according to the manufactures protocols (Diaclone and R&D Systems, respectively). Briefly, 5 × 104 cells isolated from tumor draining lymph nodes were cultured over night in presence or absence of peptides (SYMFECLE for B16OVA experiments and p15E for B16 experiments, both at concentration 10μg/ml). Peptide-specific IFNλ and Granzyme B positive spots were detected following the manufacturer’s protocol and manually counted under the binocular.

In vivo CTL killing assay and proliferation assay

Splenocytes were harvested and split into two populations. Target cell population was pulsed with 2 μg/ml p15E peptide for 2 h at 37°C, followed by CFSEHi (10 μM) fluorescent labeling. The control cell population was not pulsed but labeled with CFSELO (1 μM). Equal numbers of CFSEHi and CFSELO cells were mixed, followed by adoptively transfer (i.v.) into B16 tumor bearing animals. Each animal received 2 × 107 cells. CTL cytotoxic effects (decrease of CFSEHi mice which received adoptive transfer of Stat3+/+ or Stat3−/− CD8+ cells (8 × 106) were analyzed by flow cytometry (Accuri Cytometers). In proliferation assay tumor bearing Rag1−/− mice received adoptive transfer of Ova specific Stat3+/+ or Stat3−/− CD8+ cells (1 × 107 of each) labeled with CFSE. CD8+ cells proliferation was analyzed 72 h later by flow cytometry (Accuri Cytometers).

In vitro Tregs conversion

CD4+ GFP− cells sorted from splenocytes isolated from FoxP3-GFP knock-in C57BL/6 mice were co-cultured with Renca tumor cells and irradiated CD11c+ cells for 72h. Presence of CD4+ GFP+ cells was checked by flow cytometry.

T cells proliferation assay in vitro

1 × 105 per well of ova specific Stat3+/+ and Stat3−/− CD8+ cells were co-cultured with irradiated 5 × 104 cells CD11c+ in presence of OVA peptide for 72h. 18h before harvesting cells were incubated in medium containing 1μCi of (methyl-3H)-thymidine (Amersham). Radioactivity was measured as counts per minutes (CPM) on liquid scintilator (Wallac 1450 Microbeta, Perkin Elmer).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (31).

Statistics

An unpaired t test and two-way Anova test were used to calculate two-tailed p values to estimate statistical significance of differences between treatment groups. Statistically significant p values are indicated in figures as follows: ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software.

RESULTS

Ablating Stat3 within CD8+ cells allows in vivo expansion and activation of infused T cells in tumor-bearing lymphopenic host

Genetically engineering T cells prior to their infusion into animals or patients has greatly facilitated the advancement of adoptive T cell transfer therapeutic modality (27). To test whether Stat3 is a molecular target to inhibit in CD8+ T cells before adoptive transfer, we first generated transgenic mice lacking the Stat3 alleles in T cells. This was achieved by crossing mice containing Stat3 alleles flanked by loxP sites with mice carrying Cre recombinase transgene under control of the CD4 promoter, which deletes loxP-flanked alleles in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with very high efficiency. These mice served as donors of naive T cells for adoptive transfer into immunodeficient Rag1−/− mice that lack both T and B cells. Some of current adoptive T cell therapy protocols prior to T cells infusion introduce chemo-lymphodepletion alone or combined with radiation (28, 29). Adoptive transfer of Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells before tumor implantation significantly inhibited growth of poorly immunogenic B16 melanoma tumors in comparison to control mice that received Stat3 positive T cells (Fig. 1A). In mice receiving Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells, tumor tissue was highly infiltrated by CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1B, upper). In addition to a large increase in the total number of CD8+ T cell infiltrates, the percent of Trp2 antigen-specific T cells was also increased (Fig. 1B, lower and Supplementary Fig. 1). To further explore antigen-specific cytotoxic responses of transferred T cells, we performed in vivo killing assay in Rag1−/− mice bearing B16 melanoma tumor. Results from the assay showed that Stat3−/− CD8+ T cell killing of p15E peptide pulsed splenocytes was significantly better (Fig. 1C). Moreover, adoptive transfer of Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells into Rag1−/− mice with established B16 melanoma tumor significantly reduced tumor growth (Fig. 1C, left). B16 tumor-bearing mice receiving Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells mounted stronger responses against the endogenous B16 tumor antigen p15E than their Stat3+/+ counterparts, as shown by IFN-λ ELISPOT (Fig. 1C, right).

Figure 1. Ablating Stat3 in CD8+ T cells allows their in vivo antitumor effects.

A. B16 tumor growth is significantly inhibited in Rag1−/− mice receiving Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells. Mice received adoptive transfer of 8 × 106 CD8+ cells 1 day prior to tumor challenge (1 × 105 B16 melanoma cells sc.). Shown are the results representative of two independent experiments, n=4–5 per group for each experiment. *** P<0.001. B. Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells efficiently infiltrate tumors with and increase of Trp2 antigen-specific T cells. Shown are flow cytometry data after extracellular staining with CD8, CD90.2 antibodies. Data are representative of two experiments, using tumor pooled from 4–5 animals per group. To detect Trp2 antigen-specific T cells, samples were stained with PE-conjugated Pro5 pentamer. C. Stat3−/− CD8+ T cell killing of p15E peptide pulsed splenocytes is more efficient, shown by decrease of CFSEHi population. Left panel, example of flow cytometry analysis; right panel, summary of FACS data (mean values, ± SEM, n=2). * P<0.05. D. Left panel, Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells inhibit growth of established tumors. Mice received adoptive transfer of 8 × 106 CD8+ cells 5 d after tumor challenge (1 × 105 B16 melanoma cells sc.). Shown are the results representative of two independent experiments, n=6–8 per group for each experiment. ** P<0.01. Right panel, T cells from B16 tumor-bearing mice receiving Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells were able to mount stronger responses against an endogenous B16 tumor antigen than their Stat3+/+ counterparts, as assessed by IFN-λ ELISPOT. Data shown are mean numbers (± SEM) of p15E-specific IFN-λ–producing spots from 2 experiments with 6–8 pooled tumor draining lymph nodes. *** P<0.001. E. T cells from B16OVA tumor-bearing mice receiving Stat3−/− CD8+ OT-I cells were able to mount stronger responses after OVA peptide re-stimulation than their Stat3+/+ counterparts, as assessed by IFN-λ ELISPOT (left) and Granzyme B ELISPOT (right). Data shown are mean numbers (± SEM) of OVA specific IFN- λ/Granzyme B–producing spots from one experiment with 3 to 4 pooled tumor draining lymph nodes cells. ** P<0.01, * P<0.05.

We further evaluated whether genetically blocking Stat3 in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells would allow better T cell response in vivo. To test this, we generated ovalbumin specific mice (CD8OVA TCR (OT-I)) with or without Stat3 gene ablation in T cells. B16OVA expressing tumor growth was significantly inhibited in Rag1−/− mice receiving adoptive transfer of Stat3−/− CD8+ OT-I T cells (data not shown). B16OVA tumor-bearing mice which received Stat3−/− CD8+ OT-I cells were able to mount stronger antigen-specific T cell responses after OVA peptide re-stimulation than their Stat3+/+ counterparts, as shown by IFN-λ and Granzyme B ELISPOT (Figure 1D, left and right panel, respectively).

Tumor infiltration and proliferation of genetically engineered Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells in vivo

Although data shown in Figure 1B suggested that the lack of Stat3 in CD8+ T cells leads to efficient T cell tumor accumulation, this could be attributed to reduced tumor growth rate. To directly assess whether inhibiting Stat3 in CD8+ T cells would increase their ability to infiltrate tumors, we adoptively transferred Stat3+/+ and Stat3−/− OVA-specific CD8+ T cells mixed at 1:1 ratio into the Rag1−/− mice bearing B16OVA tumors. To distinguish between the two populations in vivo, we labeled the Stat3+/+ and Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells with distinct fluorescent cell trackers before infusion into B16OVA-tumor bearing mice. Intravital two-photon microscopy analysis of tumors performed at 48 and 72 h post adoptive transfer indicated enhanced accumulation of Stat3−/− CD8+ OT-I T cells in tumors (Fig. 2A). Flow cytometry to confirm the live microscopy imaging data showed significantly increased accumulation of Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells inside the tumors after 48 h (Fig. 2B). This finding was further confirmed using Stat3+/+ and Stat3−/− OVA-specific CD8+ T cells with reverse color labeling (Fig. 1B).

Figure 2. Deleting Stat3 in CD8+ T cells improves their tumor infiltration and proliferation.

A Left panel, isolated OVA specific CD8+ T cells were labeled with CMAC (Stat3+/+ population, blue) or CMTMR (Stat3−/− population, red), mixed at 1:1 ratio and adoptively transferred into tumor-bearing mice. Tumors were visualized for CD8+ T cell infiltration by IVMPM 48 h after adoptive transfer; ECM is shown by 2HG (grey). Right panel, similar experiment using isolated OVA specific CD8+ T cells labeled with CMTMR (Stat3+/+ population, red) or CMAC (Stat3−/− population, blue) (opposite color scheme relative to left panel), were mixed at 1:1 ratio prior to transferring into tumor-bearing mice. Tumors were analyzed for CD8+ T cell infiltration by IVMPM 72 h after adoptive transfer. B. Tumors analyzed by IVMPM 48 after adoptive transfer were then harvested and single cell suspensions were prepared for FACS analysis, left panel. Summary of FACS data is shown in the right panel. (mean values, ± SEM, n=3; * P<0.05). C Adoptively transferred Stat3−/− CD8+ OT-I T cells proliferated better in both lymph nodes. B16 tumor bearing Rag1−/− mice received adoptive transfer of Ova-specific Stat3+/+ or Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells (1 × 107 of each) labeled with CFSE. Left panel, summary of FACS data (mean values, ± SEM); right panels, examples of FACS analysis (red line – contra-lateral lymph node, black line - tumor draining lymph node, green line – initial transferred CFSE labeled CD8+ T cells). ** P<0.01, * P<0.05.

Another major challenge facing adoptive T cell therapy is the need to expand the number of T cells ex vivo. We therefore tested whether inhibiting Stat3 in transferred T cells would allow them to proliferate in vivo in the tumor-bearing hosts. Our in vivo experiments indicated that adoptively transferred Stat3−/− CD8+ OT-I T cells proliferated better both in tumor-draining and contra-lateral lymph nodes (Fig. 2C). Experiments performed in vitro confirmed higher proliferative potential of Stat3−/− Ova-specific CD8+ cells as well as elevated IFN-λ secretion after antigen-specific stimulation in the presence of tumor factors (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Targeting Stat3 systemically by sunitinib improves T cell therapy

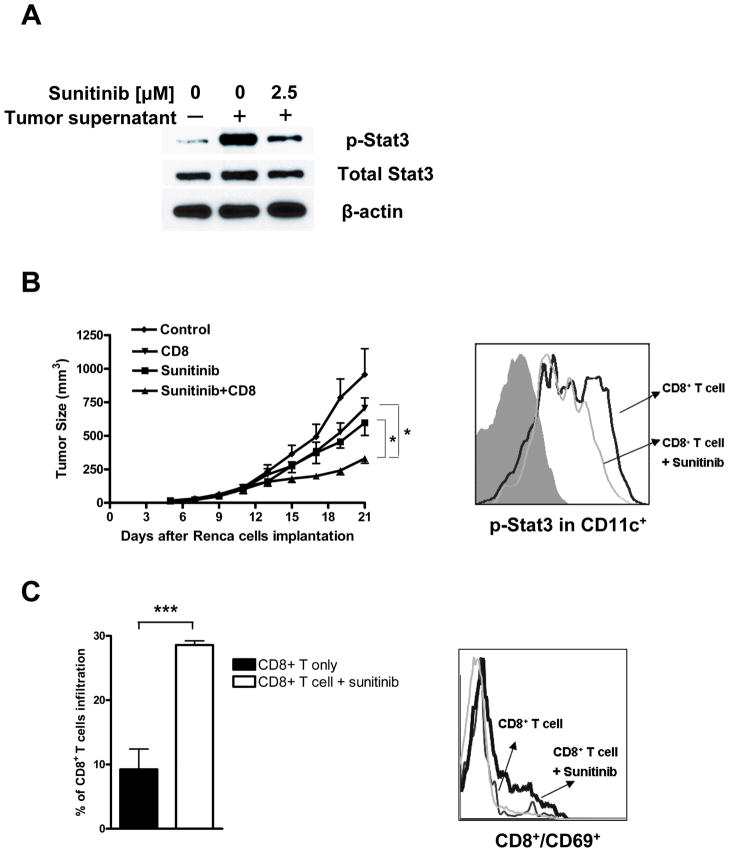

While genetic engineering of T cells prior to adoptive transfer has been an important approach for T cell therapy (27), the availability of some FDA approved small-molecule drugs with capacity to inhibit angiogenesis, kill tumor cells and modulate the tumor immunologic microenvironment, in part through Stat3 inhibition, may lead to new paradigm for T cell therapy. We therefore tested in vitro whether_sunitinib, which inhibits Stat3 (26) could effectively inhibit activation of Stat3 by tumor derived factors. Data shown in Figure 3A indicated that tumor factor-induced Stat3 activation in CD8+ T cells was inhibited by sunitinib. To asses whether sunitinib might improve adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells antitumor efficacy in vivo, Rag2−/− mice (Balb/c) with established syngeneic Renca mouse renal cell carcinoma were given vehicle control or sunitinib two days prior to T cell transfer. Results from these experiments indicated that sunitinib treatment combined with CD8+ T cell adoptive transfer inhibited growth of Renca tumor significantly better than either treatment alone (Fig. 3B, left). Moreover, systemic treatment with sunitinib inhibited Stat3 activity in tumor infiltrating dendritic cells, as shown by intracellular flow cytometry (Fig. 3B, right).

Figure 3. Sunitinib treatment inhibits Stat3 and improves CD8+ T cell antitumor effects.

A. Sunitinib treatment inhibits Stat3 activity in CD8+ T cells. Representative western blot analysis of CD8+ T cells cultured in vitro overnight in tumor supernatant conditioned media with or without sunitinib (2.5 μM). B Left panel, sunitinib treatment combined with CD8+ T cell adoptive transfer led to improved antitumor effects. Rag2−/− mice with established Renca tumors were given control vehicle or sunitinib starting 2 d before CD8+ T cells transfer. Mice were treated with sunitinib administered orally at 30mg/kg body weight once a day. Right panel, sunitinib inhibits Stat3 activity in tumor infiltrating dendrtic cells. Tumor infiltrating dendritic cells (CD11c+) were enriched from Renca tumors and analyzed for phosphorylated Stat3 by intracellular flow cytometry. * P<0.05. C. Sunitinib treatment significantly improved CD8+ T cell tumor infiltration and activation of transferred CD8+ T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Data shown are flow cytometry analyses following staining with CD8+ and early activation marker CD69. Mean values (± SEM) for detecting CD8+ T cells from two independent experiments are shown. ** P<0.01.

Inhibiting Stat3 activity by sunitinib led to increased tumor infiltration and activation of the transferred CD8+ T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes (Fig. 3C, left and right, respectively). To assess whether the positive effects of sunitinib on CD8+ T cells were at least partially through modulating Stat3 within CD8+ T cells, we combined sunitinib treatment with adoptively transferred Stat3+/+ and Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells. Subsequent analysis of CD8+ T cell tumor infiltration and activation suggested that systemic sunitinib treatment did affect CD8+ T cells, since treating mice receiving Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells with sunitinib did not further significantly enhance the T cell functions (Supplementary Fig. 3).

We also combined sunitinib treatment with adoptively transferring antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. C57BL6 mice with progressively growing B16OVA tumor (4 to 6 mm in diameter) were treated with either vehicle or sunitinib, followed by adoptive transfer of naïve OVA-specific CD8+ T cells. In mice that received the combination of both antigen-specific T cells and sunitinib, tumor growth was significantly reduced (Fig. 4A). Moreover, sunitinib-treated mice showed an increased number of activated total CD8+ T cells in tumors (Fig. 4B). To distinguish the effect of sunitinib treatment on activation of host versus transferred antigen-specific T cells, we performed experiments similar to those shown in Figure 4B but in GFP+ transgenic mice. Again, sunitinib treatment caused increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the tumor tissue and induced activation of both host and transferred T cells (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Sunitinib enhances antigen-specific antitumor response of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells.

A. Sunitinib treatment combined with adoptive T cell therapy significantly reduced growth of B16OVA tumor. C57BL6 mice were treated with sunitinib administered orally at dose of 40mg/kg body weight once a day. Two days later some of the mice received adoptive transfer of 1 × 107 ova specific CD8+ T cells. Shown representative tumor growth curve of three experiments, n= 3–6 animals per group, *** P<0.001. B. Flow analysis of tumor tissues indicated increased activation of CD8+ T cells. Shown are mean values (± SEM) of FACS analysis from three independent experiments, using pooled tumors. * P<0.05. C In vivo treatment with sunitinib increased tumor infiltration of CD8+ T cells, leading to activation of both host and transferred T cells. GFP+ transgenic mice bearing B16OVA tumors were treated as in Figure 4A. Summary of FACS analysis (mean values, ± SEM) of total infiltration of CD8+ T cells in the tumor tissues as well as presence of early activation marker CD69 on GFP+ or GFP− CD8+ T cells. n=4 *, P<0.05. D Sunitinib can affect Stat3 activity in tumor infiltrating CD8+ T cells in vivo. Left and middle panels: confocal microscopic photos of p-Stat3 nuclear staining of frozen sections of B16OVA tumors collected from mice treated with vehicle or sunitinib. CD8 (red), p-Stat3 (green), Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm. Right panel,, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI; 12 bit rate) for p-Stat3 staining in CD8+ T cells. Data include three views per tumor section and two tumors per treatment group. ** P<0.01.

In vitro analysis indicated that sunitinib can inhibit tumor factor-induced Stat3 activity in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3A). We next evaluated whether sunitinib could also reduce activated Stat3 in CD8+ T cells in tumors in vivo. Tumor tissue sections from mice receiving transfer of naïve OVA-specific CD8+ T cells and treatment with either vehicle or sunitinib were subject to immunofluorescent staining, followed by confocal microscopic analysis. Representative photos of the tumor tissue areas with comparable numbers of CD8+ T cells indicated higher nuclear p-Stat3 in CD8+ T cells in mice receiving vehicle compared to their sunitinib-treated counterparts (Fig. 4D). Mean fluorescence intensity of the tumor CD8+ T cells p-Stat3 is also shown (Fig. 4D right panel).

Sunitinib abrogates tumor-induced Treg cell conversion from CD4+FoxP3− T cells

It has been shown that depletion of endogenous Tregs prior to T cell transfer can improve the outcome of T cell therapy (30). However, the tumor microenvironment can continually convert non-Treg (CD4+FoxP3−) T cells into Treg (CD4+FoxP3+) T cells, even after initial depletion. Although recent studies indicated that sunitinib treatment diminished Treg cells in mouse tumor models and in RCC patients (23, 25), whether sunitinib effects on Tregs were indirect or through inhibiting Treg conversion remains unknown. We have previously shown that sunitinib treatment were associated with a reduction of tumor Stat3 activity and number of Tregs in Renca murine tumor model (26). In this study we tested whether sunitinib, through inhibition of Stat3 phosphorylation, hindered tumor-induced conversion of CD4+FoxP3− T cells into CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells in vitro and in vivo. Isolated CD4+FoxP3− (non-GFP-expressing) cells from FoxP3-GFP knock-in C57BL/6 mice that express GFP under the control of the promoter of FoxP3 were co-cultured with DCs and Renca tumor cells in the presence of sunitinib or vehicle (DMSO). After 3 days in culture, FoxP3 expression in CD4+ T cells was examined by flow cytometry. In comparison to the control treatment, sunitinib inhibited Treg conversion in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). To evaluate the effects of sunitinib on Stat3 signaling, we determined levels of Stat3 phosphorylation in CD4+ T cells by western blot and flow cytometry. A significant and dose-dependent inhibition of Stat3 activity in CD4+ T cells treated with sunitinib was detected by both methods (Fig. 5B, right and left, respectively).

Figure 5. Sunitinib abrogates tumor-induced conversion of CD4+FoxP3 T cells into CD4+FoxP3+Treg cells in vitro and in vivo.

A. Sunitinib abrogates tumor induced Tregs conversion in vitro. CD4+FoxP3− T cells from FoxP3-GFP knock-in mice were sorted and co-cultured with Renca tumor cells and DCs with or without sunitinib at indicated concentrations. The percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs was analyzed by FACS. Shown are representative flow cytometry results, with calculated mean values (± SEM) from three experiments (panels right and left, respectively). B. Sunitinib treatment causes dose-dependent inhibition of Stat3 activity in CD4+ T cells. Representative western blot and flow analysis of CD4+ T cells are shown (panels left and right, respectively). C. Intravital multi-photon microscopy analysis to detect conversion of CD4+FoxP3− to CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs (green) in B16 tumors, at seven and ten days since initial sunitinib treatment. Vasculature is visualized by i.v. injection of dextran- rhodamine (red color) 15 min before imaging. D. Immunofluorescence staining of B16 tumors to confirm reduction of tumor-associated Treg conversion in mice treated with sunitinib; FoxP3 (green) and CD4 (red).

To investigate the effect of sunitinib on Treg conversion in vivo, sorted CD4+FoxP T cells from FoxP3-GFP knock in C57BL/6 mice were adoptively transferred into Rag1−/− mice. Mice were then challenged with B16 tumor cells. After tumors reached 5–7 mm in diameter, sunitinib or control vehicle was administered orally. To evaluate Treg conversion in tumors, we performed intravital two-photon microscopy of tumors to detect CD4+FoxP3+ T cells. FoxP3+ Treg cells were observed in control group, but absent in the sunitinib treatment group, at various time points (Fig. 5C). Since intravital multiphoton microscopy evaluates only the surface layers of the tumor tissue, we performed immunofluorescence staining of tumor tissues, which confirmed a reduction of FoxP3 positive CD4+ cells infiltrating tumors in the sunitinib-treated group (Fig. 5D & Supplementary Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

The tumor microenvironment severely limits the efficacy of various immunotherapies. For adoptive T cell therapy, the need to select/engineer and expand T cells with targeted antigen specificity while still preserving their effector function and homing capacities poses additional challenges. The current study has identified strategies to overcome some of these obstacles facing adoptive T cell therapy. We show that genetically engineered Stat3−/− CD8+ T cells are able to, without any ex vivo expansion, efficiently proliferate, infiltrate tumor and inhibit tumor growth. Furthermore, systemic treatment with sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that affects Stat3 signaling pathway, can enhance adoptive T cell therapy and effectively inhibit tumor Treg conversion. These studies provide direct evidence that blocking Stat3 in either T cells prior to in vivo infusion or systemically in the tumor microenvironment before and/or during T cell therapy allows in vivo expansion and improved antitumor functions of the transferred T cells in lymphopenic mice.

We and others have demonstrated that Stat3 is a key oncogenic transcription factor persistently activated in diverse cancer cells and important for tumor cell survival. Stat3 is also activated in tumor stromal immune cells and potently immunosuppressive (16, 31). Multiple studies have shown that Stat3 activity in both tumor cells and tumor-associated myeloid cells plays a critical role in inducing immunosuppression, that targeted Stat3 gene ablation in myeloid cells results in tumor DC activation, tumor Treg cell reduction and heavy infiltration of CD8+ T cells in tumors, leading to effective antitumor immune responses (4, 11). Several recent studies further demonstrated the feasibility of targeting Stat3 in the tumor microenvironment to enhance various immunotherapeutic methods (17, 32, 33). Related to current study, it has been shown that targeting Stat3 systemically by an experimental Jak inhibitor altered the tumor immunological environment, leading to improved antitumor effects of transferred CTLs (34). However, the potential direct effects on T cells and Tregs by the Jak inhibitor were not assessed in the study.

Our results show that ablating Stat3 in CD8+ T cells prior to transfer allows more efficient T cell tumor infiltration, proliferation and anti-tumor effector functions. Genetically modifying selected T cells is a key part of current adoptive T cell therapy, and several approaches to engineer T cells have led to important advancement for the treatment modality (29, 35). Based on our results, it may be highly desirable to modify T cells to render the selected T cells Stat3 null before infusion into patients. This can be achieved by transducing T cells with retroviral and possibly other vectors encoding either Stat3 siRNA or dominant-negative Stat3 mutant. Furthermore, it is likely that additionally silencing/inhibiting Stat3 in the genetically engineered T cells with the capacity to homing to specific tumor sites and/or antitumor properties will improve current T cell therapeutic approaches. The improvements can possibly include shortened time for ex vivo expansion, resistance to the tumor immunosuppressive effects and better antitumor effector functions.

Combining immunotherapy with other anti-cancer therapeutic modalities can potentiate its antitumor activity by multiple mechanisms, including induced lymphodepletion, activation of antigen presenting cells or elimination of immunosuppressive populations of cells infiltrating the tumor microenvironment (28, 36, 37). Recent data has demonstrated that sunitinib can modulate immunosuppression within the tumor microenvironment by decreasing MDSCs and Tregs (22, 23, 25, 26). Furthermore, we have shown that inhibition of Stat3 signaling by sunitinib is a mechanism for this activity, which leads to a reduction in angiogenesis, increased apoptosis and decreased tumor growth (26). Our results suggest that Stat3 activity is important not only for direct RCC response to sunitinib through apoptosis but also is involved in the regulation of dendritic cells activation, MDSC infiltration and T regulatory cells accumulation in the tumor tissue. Systemic treatment of renal cell carcinoma and melanoma in immunodeficient mice combined with adoptive transfer of naïve CD8+ T cells significantly inhibited their growth. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of Stat3 negative CD8+ T cells enhanced the antitumor responses, indicating importance of inhibition of Stat3 signaling in all compartments of immune system.

Sunitininb treatment significantly improved antitumor responses with adoptive transfer of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. This observation is in agreement with studies by Ozao-Choy et al, who demonstrated that sunitinib improved antitumor responses when using tumor specific CD4+ T cells (25). Released factors such as TGF-β can convert Th1 CD4+ T cells into regulatory cells which actively suppress antitumor immune response (38). In this report, we show that sunitinib treatment inhibits Stat3 phosphorylation, and abrogates tumor microenvironment-induced conversion of CD4+ cells into T regulatory cells both in vitro and in vivo. These observations concur with recent studies which implicate sunitinib Stat3 inhibition in the reduction of Tregs at the tumor site (25, 39) and provide a potential mechanism whereby Tregs are not only depleted by Stat3 inhibition, but their conversion is also blocked.

Enthusiasm for adoptive T cell therapy remains high, and as we better understand how to generate T cells with improved specificity, durability and cytotoxicity, we must also determine appropriate and clinically feasible methods to address immunosuppression within the tumor microenvironment. Our data demonstrate that sunitinib therapy can enhance adoptive T cell therapy, at least partially, through the inhibition of Stat3 signaling, with subsequent reversal of immunosuppression at the tumor site. These results present a paradigm that may be used in the clinic: blocking Stat3 in T cells prior to transfer, and/or using Stat3 inhibitory tyrosine kinase inhibitors to improve the efficacy of T cell therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Analytical Cytometry Core, the Light Microscopy Core and Animal Facility at City of Hope for their contributions. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01CA122976 and R01CA146092), and by Kure it! Kidney Cancer Funds at City of Hope Medical Center.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.June CH. Adoptive T cell therapy for cancer in the clinic. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1466–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI32446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.June CH. Principles of adoptive T cell cancer therapy. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1204–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI31446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:24–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–74. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang HY, Wang RF. Regulatory T cells and cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blank C, Gajewski TF, Mackensen A. Interaction of PD-L1 on tumor cells with PD-1 on tumor-specific T cells as a mechanism of immune evasion: implications for tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:307–14. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0593-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu H, Jove R. The STATs of cancer new molecular targets come of age. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:97–105. doi: 10.1038/nrc1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinjyo I, Inoue H, Hamano S, et al. Loss of SOCS3 in T helper cells resulted in reduced immune responses and hyperproduction of interleukin 10 and transforming growth factor-{beta}1. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1021–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kortylewski M, Xin H, Kujawski M, et al. Regulation of the IL-23 and IL-12 balance by Stat3 signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:114–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niu G, Wright KL, Huang M, et al. Constitutive Stat3 activity up-regulates VEGF expression and tumor angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:2000–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng P, Corzo CA, Luetteke N, et al. Inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer is regulated by S100A9 protein. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2235–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kortylewski M, Kujawski M, Wang T, et al. Inhibiting Stat3 signaling in the hematopoietic system elicits multicomponent antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2005;11:1314–21. doi: 10.1038/nm1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kortylewski M, Swiderski P, Herrmann A, et al. In vivo delivery of siRNA to immune cells by conjugation to a TLR9 agonist enhances antitumor immune responses. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:925–32. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faivre S, Demetri G, Sargent W, Raymond E. Molecular basis for sunitinib efficacy and future clinical development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:734–45. doi: 10.1038/nrd2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendel DB, Laird AD, Xin X, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:327–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckstein R, Meyer RM, Seymour L, et al. Phase II testing of sunitinib: the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group IND Program Trials IND. 182–185. Curr Oncol. 2007;14:154–61. doi: 10.3747/co.2007.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finke JH, Rini B, Ireland J, et al. Sunitinib reverses type-1 immune suppression and decreases T-regulatory cells in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6674–82. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko JS, Zea AH, Rini BI, et al. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2148–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abe F, Younos I, Westphal S, et al. Therapeutic activity of sunitinib for Her2/neu induced mammary cancer in FVB mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;10:140–45. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozao-Choy J, Ma G, Kao J, et al. The novel role of tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the reversal of immune suppression and modulation of tumor microenvironment for immune-based cancer therapies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2514–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xin H, Zhang C, Herrmann A, Du Y, Figlin R, Yu H. Sunitinib inhibition of Stat3 induces renal cell carcinoma tumor cell apoptosis and reduces immunosuppressive cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2506–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.June CH, Blazar BR, Riley JL. Engineering lymphocyte subsets: tools, trials and tribulations. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:704–16. doi: 10.1038/nri2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5233–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, et al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314:126–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Q, Bucher C, Munger ME, et al. Depletion of endogenous tumor-associated regulatory T cells improves the efficacy of adoptive cytotoxic T-cell immunotherapy in murine acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:3793–802. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kujawski M, Kortylewski M, Lee H, Herrmann A, Kay H, Yu H. Stat3 mediates myeloid cell-dependent tumor angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3367–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI35213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kong LY, Abou-Ghazal MK, Wei J, et al. A novel inhibitor of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 activation is efficacious against established central nervous system melanoma and inhibits regulatory T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5759–68. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nefedova Y, Nagaraj S, Rosenbauer A, Muro-Cacho C, Sebti SM, Gabrilovich DI. Regulation of dendritic cell differentiation and antitumor immune response in cancer by pharmacologic-selective inhibition of the janus-activated kinase 2/signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 pathway. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9525–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujita M, Zhu X, Sasaki K, et al. Inhibition of STAT3 promotes the efficacy of adoptive transfer therapy using type-1 CTLs by modulation of the immunological microenvironment in a murine intracranial glioma. J Immunol. 2008;180:2089–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pule MA, Savoldo B, Myers GD, et al. Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma. Nat Med. 2008;14:1264–70. doi: 10.1038/nm.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zitvogel L, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Kroemer G. Immunological aspects of cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:59–73. doi: 10.1038/nri2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teitz-Tennenbaum S, Li Q, Davis MA, et al. Radiotherapy combined with intratumoral dendritic cell vaccination enhances the therapeutic efficacy of adoptive T-cell transfer. J Immunother. 2009;32:602–12. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181a95165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25- naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pallandre JR, Brillard E, Crehange G, et al. Role of STAT3 in CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory lymphocyte generation: implications in graft-versus-host disease and antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2007;179:7593–604. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.