There is ample evidence of the RBD-neurodegenerative disease association, and RBD associated with the synucleinopathies is particularly strong.1–4 Many patients with isolated RBD, often termed “idiopathic RBD” and abbreviated “iRBD”, subsequently develop cognitive impairment and/or parkinsonism, which is typically manifested as the syndromes of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), MCI with parkinsonism, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), Parkinson disease (PD), or PD with dementia.5 Investigators are increasingly attempting to identify the earliest features of an evolving neurodegenerative syndrome in those with iRBD, as such information permits better understanding of disease burden, progression, and prognostication.

Neuropsychological testing can be viewed as a biomarker, and impairment in one or more cognitive domains is a critical correlate for the identification of evolving MCI or dementia due to an underlying neurodegenerative disorder. Impairment can also precede overt neurobehavioral dysfunction, thus providing a means to identify those patients who will likely become symptomatic in the near future. The article authored by Fantini and colleagues6 in this issue of SLEEP provides important insights into the early and presumably clinically inapparent neurocognitive deficits in those with iRBD. These investigators compared neuropsychological test scores between a group of iRBD subjects (n = 24) to a group of normal control subjects (n = 12) at baseline, and at follow-up evaluation approximately two years later. The main findings revealed significantly worse performance in the iRBD group compared to normal controls at baseline and follow-up on tasks of visuoconstruction and verbal memory. On follow-up, the iRBD group also performed worse on a visuospatial supraspan attention task. The number of subjects with abnormal scores in these cognitive tasks using an Equivalent Score method was also greater in those with iRBD than in the normal control group. No data on the longitudinal course of specific subjects were provided.

Whether this group of patients with iRBD will develop other features consistent with an evolving neurodegenerative disorder remains to be seen. It may be anticipated that other features of Lewy body disease (LBD) will develop in many by virtue of the higher prevalence of LBD compared to other diseases associated with RBD.5 Cross-sectional analyses in iRBD subjects and in those with RBD associated with MCI or dementia have revealed a relatively consistent pattern of neuropsychological profiles. The dementia phenotype associated with RBD is usually DLB, in which impairment in attention/executive functioning and visuoconstructive/visuospatial functioning is typical.7–9 These same domains tend to be affected in those patients with RBD who are also diagnosed with MCI,10 including those with MCI who subsequently develop the full DLB syndrome and ultimately have pathologic evidence of Lewy body disease.11 Yet among those with RBD plus MCI, there is some degree of neuropsychological variability, with some presenting with only one domain affected, while others may have additional impairment in learning and memory.11 As shown in the article by Fantini et al.,6 and as previously demonstrated,12–14 the domains of learning and memory, attention/executive functioning, and visuoconstructive/visuospatial functioning can be affected in the asymptomatic/minimally symptomatic cognitive phase. Therefore, these data substantiate the utility of neuropsychological testing in identifying iRBD patients who likely have an underlying neurodegenerative disorder, which is probably underlying LBD, particularly when these cognitive domains are impaired.

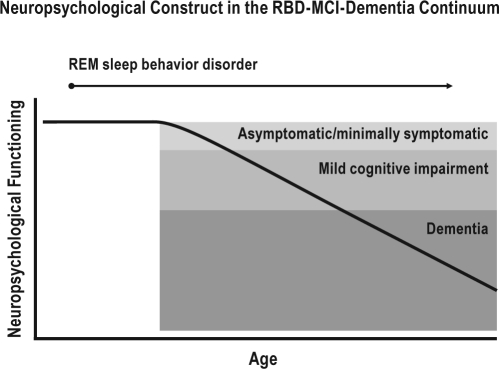

These hypotheses have yet to be proven, and many questions remain. Among those with iRBD, when is impairment on neurocognitive performance first apparent? Which neurocognitive tests are optimal to use for early detection, and which are optimal to characterize decline over time? Importantly, the cross-sectional data suggest that there may be an evolution from asymptomatic/minimally symptomatic neuropsychological impairment, to MCI, and ultimately to dementia (as depicted in Figure 1). It is still uncertain, however, whether this progression actually occurs, and if so, whether it evolves in a predictable manner with a projected time course. This issue is crucial to the planning of future intervention studies. There is also a critical need to identify which affected neural networks underlie the neurocognitive deficits, and to determine the time course of changes in these pathological substrates relative to progression of neurocognitive impairments. These are some of many critical questions which will require comprehensive longitudinal studies in iRBD subjects—these questions could not be answered within the focused scope of the analysis by Fantini et al.6

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the proposed neuropsychological construct in the REM sleep behavior (RBD)-mild cognitive impairment (MCI)-dementia continuum.

Some of the observations in the data by Fantini et al. also underscore the challenges of longitudinal characterization, the spectrum of the underlying causes of iRBD and the variably associated neuropsychological deficits, and the variability of manifestations associated with neurodegenerative disorders themselves (such as LBD). The small sample size of the study also limits generalizability, and hence there remains a need for replication with further longitudinal clinical follow-up and neuropathologic examination. We commend Fantini and colleagues for assessing iRBD subjects in a standardized longitudinal manner, and urge increased identification of iRBD subjects and their participation in long-term comprehensive assessments involving neuropsychological testing and other potential biomarkers.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Dr. Boeve has served as an investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Cephalon, Inc., and Allon Pharmaceuticals. He receives royalties from the publication of a book entitled Behavioral Neurology of Dementia (Cambridge Medicine, 2009). He has received honoraria from the American Academy of Neurology. He receives research support from the National Institute on Aging [P50 AG16574 (Co-Investigator), U01 AG06786 (Co-Investigator), RO1 AG15866 (Co-Investigator), RO1 AG32306 (Co-Investigator)], the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) [U24 AG026395 (Co-Investigator)], and the Mangurian Foundation for Lewy Body Dementia Research.

Dr. Ferman receives research support from the National Institute on Aging [RO1 AG15866 (Principal Investigator), and the Mangurian Foundation for Lewy Body Dementia Research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants AG 15866, AG 16574, and AG 06786, The Mangurian Foundation for Lewy Body Dementia Research, and the Robert H. and Clarice Smith and Abigail Van Buren Alzheimers Disease Research Program of the Mayo Foundation. The authors acknowledge the mentorship and contributions of our many collaborators on aging and neurodegenerative disease research, particularly Glenn E. Smith, PhD on the neuropsychology of RBD, MCI, and DLB.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boeve B, Silber M, Parisi J, et al. Synucleinopathy pathology and REM sleep behavior disorder plus dementia or parkinsonism. Neurology. 2003;61:40–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073619.94467.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iranzo A, Molinuevo J, Santamaría J, et al. Rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder as an early marker for a neurodegenerative disorder: a descriptive study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:572–7. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagnon J-F, Postuma R, Mazza S, et al. Rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder and neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:424–32. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeve B, Silber M, Saper C, et al. Pathophysiology of REM sleep behaviour disorder and relevance to neurodegenerative disease. Brain. 2007;130:2770–88. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boeve B. REM sleep behavior disorder: Updated review of the core features, the REM sleep behavior disorder-neurodegenerative disease association, evolving concepts, controversies, and future directions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1184:17–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fantini M, Faini E, Ortelli P, et al. Longitudinal study of cognitive function in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2011;34:619–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Smith GE, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder and dementia: cognitive differences when compared with AD. Neurology. 1999;52:951–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferman T, Boeve B, Smith G, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies may present as dementia with REM sleep behavior disorder without parkinsonism or hallucinations. J Internat Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:907–14. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702870047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferman T, Smith G, Boeve B, et al. Neuropsychological differentiation of dementia with Lewy bodies from normal aging and Alzheimer's disease. Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;20:623–36. doi: 10.1080/13854040500376831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagnon J, Vendette M, Postuma R, et al. Mild cognitive impairment in rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:39–47. doi: 10.1002/ana.21680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molano J, Boeve B, Ferman T, et al. Mild cognitive impairment associated with limbic and neocortical Lewy body disease: A clinicopathological study. Brain. 2010;133:540–56. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferini-Strambi L, Di Gioia M, Castronovo V, et al. Neuropsychological assessment in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD): Does the idiopathic form of RBD really exist? Neurology. 2004;62:41–45. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000101726.69701.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terzaghi M, Sinforiani E, Zucchella C, et al. Cognitive performance in REM sleep behaviour disorder: a possible early marker of neurodegenerative disease? Sleep Med. 2008;9:343–51. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massicotte-Marquez J, Décary A, Gagnon J, et al. Executive dysfunction and memory impairment in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology. 2008;70:1250–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000286943.79593.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]