Abstract

Previous research suggests that synchronous cortical gamma-band oscillations reflect the implementation of cognitive control in anticipation of the need to overcome prepotent responses. These studies often require participants to link task instructions with task cues signaling the need (or lack thereof ) for cognitive control. Thus, the oscillatory response elicited by these cues may also reflect the implementation of explicit task instructions. The aim of this research was to determine whether gamma-band oscillations would also be increased in preparation for cognitive control when the need for that control was only made implicitly available to the participant. Using a task-ambiguous cue to indicate the position of a subsequent probe stimulus, we manipulated the need for cognitive control by varying the probability of high- and low-control probes appearing in each of two positions. Results show that participants developed the anticipated expectancies regarding probe identity in the two positions and that the anticipation of a high-control probe was associated with an increase in the power of induced cortical gamma band over frontal scalp recording sites.

Synchronized cortical oscillations in the gamma (30–80 Hz) frequency band have been linked with a number of perceptual and cognitive processes including perceptual binding (Gray, Konig, Engel, & Singer, 1989) and attention (Tittinen et al., 1993). The fact that changes in synchronized gamma-band responses can be elicited under such a wide variety of conditions has led some to posit that these oscillations may reflect a generic mechanism that can also be utilized for activating neural ensembles required for cognitive control (Cho, Konecky, & Carter, 2006; Fan et al., 2007).

Cognitive control refers to a collection of processes responsible for the direction of goal-relevant information processing (Botvinick, Braver, Barch, Carter, & Cohen, 2001; Schneider & Detwiler, 1987). The flexibility of human behavior and, in particular, the ability to modulate our behavior in accordance with dynamic contextual and/or motivational factors is thought to be a direct reflection of this capacity for the direction and redirection of information processing. The need for cognitive control is believed to be greatest when habitual responses must be overcome or irrelevant information must be ignored, and is commonly associated with prefrontal cortical activity in fMRI studies. Such activity can be specifically ascribed to top-down control processes in task-switching paradigms that use cues on each trial to respectively indicate responses of varying control demands to upcoming probe stimuli, with higher control trials eliciting higher activity during the intervening delay period (Barber & Carter, 2005; MacDonald, Cohen, Stenger, & Carter, 2000; Snitz et al., 2005). This activity can also be understood in terms of the active maintenance requirements during working memory paradigms, in this case maintaining more abstract task rule information to appropriately bias processing of upcoming probe stimuli (Miller & Cohen, 2001). The blood-oxygenation- level-dependent (BOLD) signal in fMRI studies has been found to correlate highly with local field potential activity in the gamma band (Logothetis, Pauls, Augath, Trinath, & Oeltermann, 2001) and EEG studies have observed increases in gamma oscillatory activity in association with working memory load (Howard et al., 2003; Tallon-Baudry, Kreiter, & Bertrand, 1999), suggesting that cognitive control representations may be supported through synchronized gamma activity in prefrontal neural networks.

Accordingly, Cho et al. (2006) employed a task requiring participants to overcome prepotent responses in order to understand the potential link between cognitive control and synchronous cortical gamma-band oscillations. Briefly, Cho et al. (2006) presented participants with red and green color patches, which served as cues indicating how to respond to subsequently presented arrows pointing either left or right. Participants were instructed to respond in the same direction as the arrow (a prepotent response; see Simon & Berbaum, 1990) following a green cue, and in the opposite direction following a red cue. Increases in induced gamma-band activity over prefrontal cortical areas were observed following the red in comparison with the green cue, suggesting a role for gamma-band activity in cognitive control. Moreover, this increase was not observed in a group of people with schizophrenia, a disorder believed to be associated with deficits of cognitive control (J. Cohen, Barch, Carter, & Servan-Schreiber, 1999).

A caveat to the interpretation of the findings by Cho et al. (2006) and to other research involving the use of explicit cues is that the procedures rely on the participant to link task instructions with discrete task cues signaling the need (or lack thereof) for control. Thus, the response elicited by these cues may also reflect the implementation of explicit task instructions. The primary aim of this research was to test the hypothesis that induced frontal cortical gamma-band oscillations would also be increased during anticipatory cognitive control when information regarding the need for that control was only made implicitly available to the participant.

Evidence using probability cues that people can respond more quickly during a visual search task when the probe stimulus appears in a location that is more likely to contain probes suggests that the control of attentional biases can be engaged in the absence of explicit instructions and/or awareness (Geng & Behrmann, 2002). Moreover, mechanisms of cognitive control reflected in synchronous neural oscillations also appear to be engaged following the commission of errors in a go/no-go task, even when those errors occur without conscious awareness (M. X. Cohen, van Gaal, Ridderinkhof, & Lamme, 2009). Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that synchronous cortical gamma-band oscillations will be elicited by demands for increased cognitive (or “attentional”) control even when participants are only implicitly aware of the need for that control.

In the present study, a task-ambiguous cue was used to indicate in which of two centrally located positions a probe would later appear; the need for control was manipulated by varying the probability of high- and low-control probes appearing in each of the two positions. Thus, the primary hypothesis is that induced frontal gamma-band activity will be modulated in accordance with the position in which the cue appears. Additionally, this procedure affords an opportunity to test the related hypothesis that requirements for cognitive control (and thus induced gamma-band activity) will also be greater in response to probes that appear in a location where they would typically be unexpected.

METHOD

Participants

Twenty-two (16 female) participants were recruited from the undergraduate participant pool at the University of Pittsburgh. Written, informed consent was obtained before testing. All participants were 18 to 21 years old (M = 18.8, SD = 0.96). One participant was removed from the analysis due to excessive noise in the electrophysiological recordings.

Procedure

Task stimuli were presented centrally on a computer monitor using E-Prime (Psychological Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA). Participants were informed that either a red or green arrow would appear in one of two locations on each trial and that the position would be randomly determined on each trial. Participants were instructed to respond to green arrows by pressing a button that corresponded with the direction of the arrow and to respond to red arrows by pressing a button in the opposite direction of the arrow. Participants were also informed that a small white circle would cue the location at which the arrow would appear on each trial and that the arrow would always appear in the cued location. Two small lines indicating the two positions remained on screen throughout the experiment. The cue (i.e., a white dot) remained on screen for 500 msec and was followed by a 500-msec interstimulus delay interval prior to probe onset. The probe (i.e., a colored arrow) remained on the screen until a response was made. Trials were separated by a 1,500-msec intertrial interval. There were 400 trials in all (200 per color). Unbeknownst to the participants, 85% of the green arrows (N = 170) appeared in only one of the two locations (hereafter referred to as the greenEX position) and 85% of the red arrows (N = 170) appeared in the other of the two locations (hereafter referred to as the redEX position). Thus, the remaining 15% of red and green arrows (N = 30 per color) appeared in the greenEX and redEX positions, respectively. The assignment of positions to color likelihoods was counterbalanced across participants. At the conclusion of the task, all of the participants were asked whether they believed red or green arrows were more or less likely to occur in either of the two locations. Seven of the 22 participants reported (all correctly) awareness of the manipulation. A schematic illustration of the task is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the task.

Recordings

EEG data were acquired using a 129 Ag–AgCl-coated carbon fiber electrode Geodesic Sensor Net (GSN; Electrical Geodesics Inc., Eugene, OR) with a sampling frequency of 250 Hz. Data were filtered online with a 0.1- to 100-Hz bandpass hardware filter. Electrode impedances were kept below 50 kΩ. All channels were referenced to Cz.

Offline processing

Data were visually inspected for segments containing muscular and skin-potential artifacts, which were removed from the continuous record. Oculomotor artifacts were corrected using independent components analysis (Makeig, Bell, Jung, & Sejnowski, 1996). All data were then re-referenced to the common average.

Time-frequency transformation

Event-related changes in gamma-band activity were characterized using a wavelet transform implemented in ERPWAVELAB (Mørup, Hansen, & Sidse, 2007), an open source toolbox extension to EEGLAB (Delorme & Makeig, 2004) running under MATLAB r2007b (The MathWorks, Inc.). The instantaneous spectral activity was computed using a complex-valued Morlet’s wavelet defined by a bandwidth parameter that was set to one. Signal power was computed for each of the cue- and probe-locked segments over the interval from −500 to 1,100 msec and over the range of frequencies from 30 to 80 Hz, in 1-Hz steps. The induced gamma-band activity, I(c, f, t), was then estimated at each channel, c, frequency, f, and time, t, as

| (1) |

where

is the average amplitude of the oscillation and

is equivalent to phase-locked or “evoked” activity derived from the time-frequency-transformed evoked potential. Thus, the induced activity reported hereafter reflects that part of the event-related changes in gamma-band power that was not phase-locked to the onset of the cue/probe events. Event-related changes in gamma-band activity were then quantified by standardizing the measures of induced signal power between 0 and 1,000 msec with respect to a 300-msec (−400 to −100 msec) precue/probe interval, respectively. This standardization improves the interpretability of differences in absolute power across the frequency spectrum and controls for individual differences in absolute power.

Task-relevant perturbations in gamma-band activity were then determined by examining task-defined (e.g., redEX − greenEX) differences in the spatial topography of the standardized induced gamma power averaged across gamma-band frequencies (30–80 Hz) and over the 0-msec to 1,000-msec epoch for each of the 129 cortical sensors and experimental conditions. Regions of interest were defined as significant modulations of activation in the topographical maps determined by visual inspection. Additionally, only modulations involving locally coherent increases/decreases in gamma power that included four or more spatially contiguous electrodes were selected for further analysis. A cluster of periocular channels ( GSN–128: 8, 17, 26, 126, 127) was used to characterize the gamma-band activity typically linked with saccadic eye movements in order to exclude potential saccade-related explanations of the results. Averages of the activity in these contiguous channels were then used to visualize the time-frequency perturbations of induced gamma-band power within each of the task conditions. Averages over the gamma-band frequencies derived from these regions of interest were submitted to statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Behavioral

Response accuracy and latency were each submitted to separate 2 (color: red, green) × 2 (position: redEX, greenEX) × 2 (block: Trials 1–200, Trials 201–400) × 2 (awareness: aware, unaware) mixed-measures ANOVAs. The block factor simply divided the experiment into two halves (200 trials each) in an effort to determine whether the anticipated interaction between color and position occurred only in the latter half of the experiment. The awareness factor was used to determine whether a participant’s explicit awareness of the manipulation had an impact on their behavior. Seven of the 21 participants included in the analysis reported being “aware” that each of the two colors was more or less likely to appear in one of the two locations. The remaining 14 were “unaware” of the manipulation.

Response accuracy

The analysis of response accuracy revealed a main effect of block [F(1,20) = 8.8, p < .01], reflecting an increase in accuracy from the first (M = 94%, SD = 3%) to the second (M = 96%, SD = 1.5%) block. There was also a significant position × color interaction [F(1,20) = 310.7, p < .001], reflecting an increase in accuracy for each color in the location in which it was least likely. Mean accuracy for responses to green arrows was 92% (SD = 2%) in the position containing 170 of the 200 green arrows in comparison with 98% (SD = 2.4%) in the position containing only 30 of the 200 green arrows. Likewise, mean accuracy for responses to red arrows was 92% (SD = 2.2%) in the position containing 170 of the 200 red arrows in comparison with 98% (SD = 3.3%) in the position containing only 30 of the 200 red arrows. There were no significant interactions with either the block or the awareness factors, indicating that (1) learning may have developed rapidly and influenced behavior across the experiment, and (2) the behavioral effects were independent of the participant’s awareness of the manipulation.

Response latency

The analysis of response latency (excluding errors) revealed a main effect of color[F(1,19) = 18.1, p < .001], reflecting reduced latency in responding to green (M = 651 msec, SD = 151 msec) in comparison with red (M = 713 msec, SD = 197 msec) arrows. There was also a main effect of block [F(1,19) = 11.1, p < .01], reflecting faster response times in the second (M = 657, SD = 164) than in the first (M = 706, SD = 183) block of trials. Finally, there was a significant position × color interaction [F(1,19) = 23.9, p < .001], consistent with the expectation that participants would develop implicit expectancies and respond more quickly when the red and green arrows appeared in those positions most likely to contain an arrow of the corresponding color (see Figure 2). The lack of any evidence for an interaction with the block factor suggests that these expectancies may have developed rapidly; all further analyses were thus collapsed across all trials of the experiment. Moreover, there was no evidence that a participant’s awareness of the manipulation interacted with the behavioral measures. Response times and accuracy rates for each color, position, and block are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mean response accuracy (A) and latency (B) grouped by color, position, and block. ITI, intertrial interval; ISI, inter-stimulus delay interval.

Electrophysiological1

Cue-locked analysis

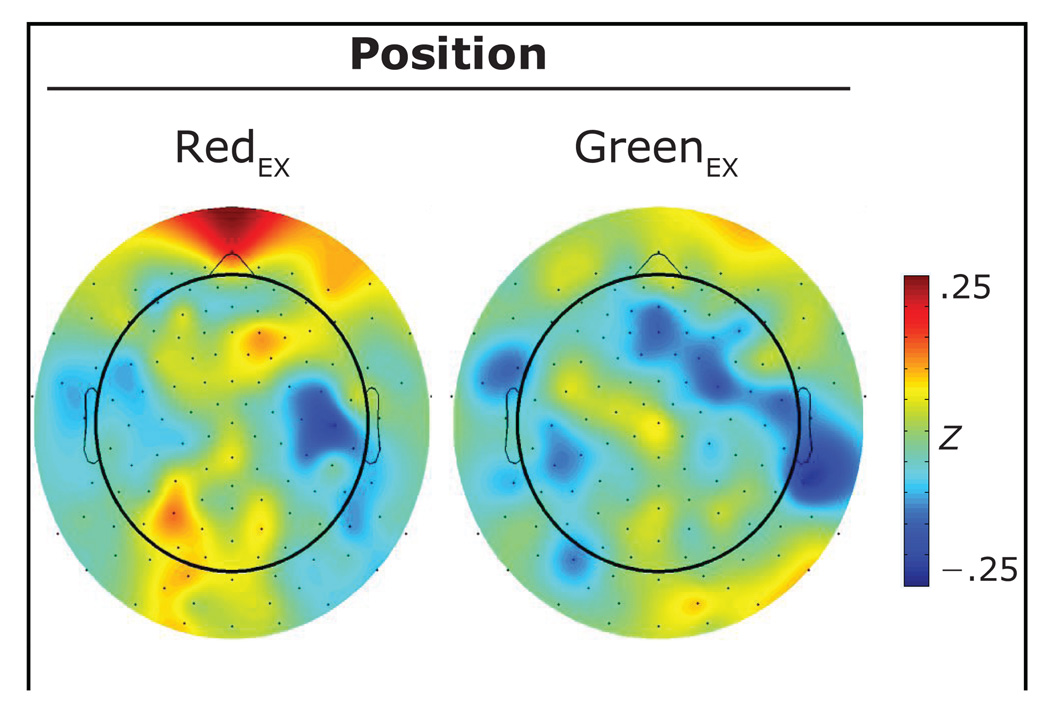

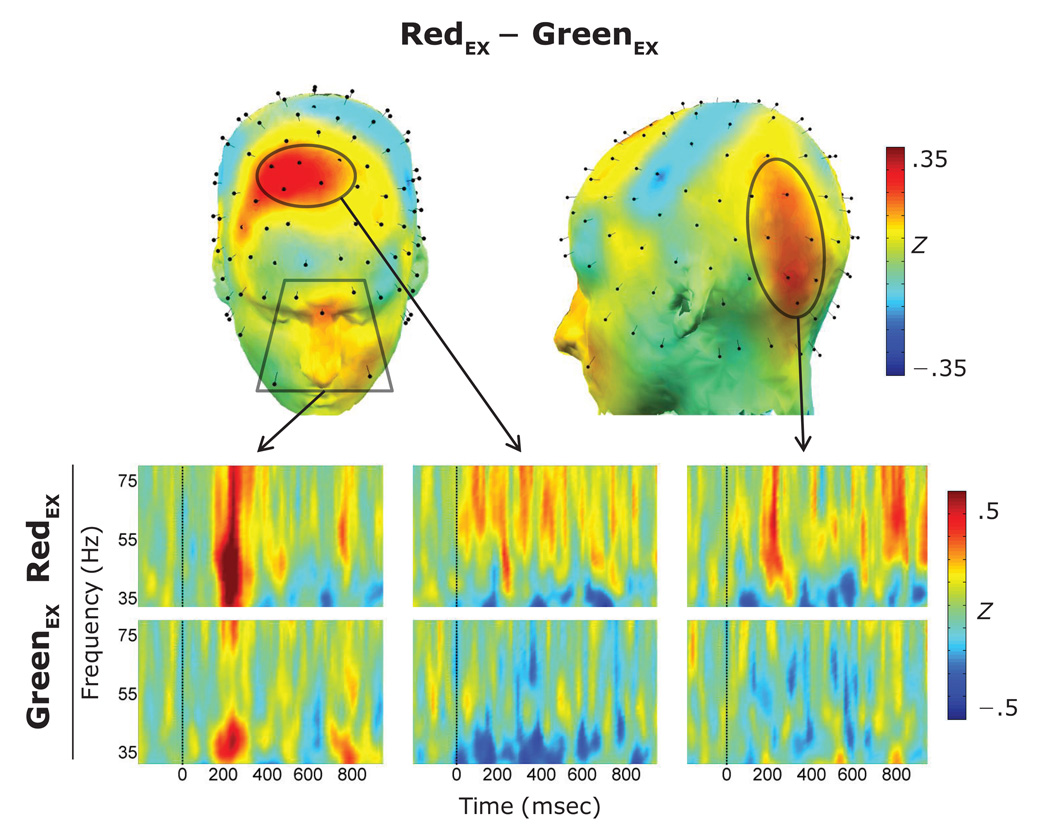

Topographical maps of the induced gamma-band activity averaged over the cue–probe interval for cues appearing in each of the two positions are presented in Figure 3. Two activation regions were identified in the topographical maps of the difference between the response to cues appearing in the redEX (i.e., 85% red arrows) and greenEX (i.e., 85% green arrows) positions (see Figure 4). On the basis of these topographical differences, analyses proceeded using five channels (GSN–128: 4, 5, 11, 119, 124) to characterize the frontal gamma-band response and six channels (GSN–128: 59, 60, 65, 66, 70, 71) to characterize the left parietal–occipital gamma. Gamma-band activity in the periocular channels possessed a clear temporal structure and was maximal over the interval between 150 msec and 350 msec. Thus, data were averaged over this interval for the group of periocular channels. Gamma-band activity began earlier and was more sustained in both the frontal and left parietal–occipital regions. Thus, data were averaged over the 0-msec to 1,000-msec cue–probe interval for these two groups of channels. Averages from each region were entered into a 2 (position: redEX, greenEX) × 2 (awareness: aware, unaware) mixed-measures ANOVA.

Figure 3.

Scalp topographies of induced gamma power over the cue–probe interval for each of the greenEX and redEX positions.

Figure 4.

(Top) Scalp topography of the difference of induced gamma power over the cue–probe interval between the greenEX and redEX positions. (Bottom) Time–frequency plots for each of the greenEX and redEX positions derived from the identified scalp regions.

Periocular

A significant main effect of position [F(1,19) = 5.7, p < .05] indicated that induced gamma-band activity was increased for the redEX (M = .64, SD = .82) in comparison with the greenEX (M = .25, SD = .36) position.

Frontal

A significant effect of position [F(1,19) = 16.1, p < .001] indicated the predicted increase of the gamma-band response over the frontal cortex following cues in the redEX position (M = .13, SD = .27); however, the magnitude of the statistical effect was due in part to a similar reduction of gamma-band activity in the greenEX (M = −.19, SD = .28) condition with respect to baseline.

Left parietal–occipital

A significant effect of position [F(1,19) = 9.9, p < .01] indicated similarities with the analysis of the frontal region. Task-relevant differences in gamma-band activity recorded over the left parietal– occipital region were driven by both increased gamma following cues in the redEX (M = .09, SD = .32) position and decreased gamma power following cues in the greenEX (M =−.11, SD = .23) position. A summary of these task-relevant differences for each of the three (periocular, frontal, and left parietal–occipital) regions is presented in Figure 5. There were no main effects or interactions involving the awareness factor in any of the three regions.

Figure 5.

Mean induced gamma power over the cue–probe interval for each of the identified scalp regions.

Probe-locked analysis

Topographical maps of the induced gamma-band activity averaged over the 0-msec to 1,000-msec probe-locked interval for each of the arrow colors appearing in each of the two positions are presented in Figure 6. From these, two topographical maps were generated in accordance with a priori predictions (see Figure 7). Contrary to predictions, there were no substantive differences in the amplitude of the induced gamma-band when comparing the response between red and green arrows. Two activation regions were identified in the topographical maps of the difference between responses to expected (e.g., red arrow in the redEX position and green arrow in the greenEX position) and unexpected (e.g., red arrow in the greenEX position and green arrow in the redEX position) probes. On the basis of these topographical differences, analyses proceeded using six channels (GSN– 128: 104, 110, 111, 112, 117, 118, 119) to characterize a right frontal region and five channels (GSN–128: 64, 65, 66, 70, 71) to characterize the left parietal–occipital region. Data were averaged over the 0-msec to 1,000-msec probe-locked interval for each of the right frontal, left parietal–occipital, and periocular regions. Averages from each region were entered into a 2 (position: redEX, greenEX) × 2 (color: red, green) × 2 (awareness: aware, unaware) mixed-measures ANOVA.

Figure 6.

Scalp topographies of induced gamma power over the probe-locked (0–1,000 msec) interval for each probe color and position.

Figure 7.

(Top) Scalp topographies of the induced gamma-band differences between red and green probes (collapsed across position) and between unexpected and expected probes (collapsed across color). (Bottom) Time–frequency plots for each of the identified scalp regions for each of the expected and unexpected conditions.

Periocular

There were no significant differences or interactions between conditions for gamma-band activity in the periocular region.

Right frontal

An interaction between position and color [F(1,19) = 11.3, p < .01] indicated that reductions in gamma-band power over right frontal scalp following probe arrows were greater when the color of those probes matched a participant’s expectations (e.g., red arrow in the redEX position and green arrow in the greenEX position).

Left parietal–occipital

The main effect of position [F(1,19) = 9.6, p < .01] indicated a significant reduction in gamma power following probes appearing in the redEX (M = −.15, SD = .23) compared with the greenEX (M = .03, SD = .23) position. However, this effect was qualified by a significant color × position interaction [F(1,19) = 8.1, p < .01], revealing that the gamma-band reductions were moderated by participants’ expectancies, occurring almost exclusively following red arrows in the redEX position (see Figure 8). There were no main effects or interactions involving the awareness factor in any of the three regions.

Figure 8.

Mean induced gamma power over the probe-locked interval for each of the identified scalp regions.

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this research was to test the prediction that induced cortical gamma-band activity would be increased during the anticipation of the need for cognitive control when the need for that control was only made implicitly available to participants. This prediction was largely confirmed by the present findings, in that induced gamma-band activity was significantly increased over frontal scalp following the appearance of task-ambiguous cues in a position typically occupied by a high-control probe (i.e., a red arrow). Moreover, perturbation of induced gamma-band power was observed over similar left posterior parietal regions following both cue and probe onset, indicating that overlapping regions of cortex are likely involved in both the preparation and implementation of control processes. Finally, experimental differences in induced gamma power were not modulated by participants’ awareness of the manipulation, suggesting that increases in anticipatory gamma-band activity during the preparing-to-overcome-prepotency (POP) task (e.g., Cho et al., 2006) are independent of the application of explicit task instructions and that cognitive control in such tasks is effectuated, at least in part, by induced oscillatory activity in the gamma band.

Interestingly, gamma-band modulations over the cue period were driven both by increases for the redEX and decreases for the greenEX conditions. This suggests that there may have been a partial representation of the high-control state that spanned blocks of trials, which was further up-modulated during redEX trials and down-modulated during greenEX trials. Given the mixed, random presentation of trial types, this could be a sensible strategic approach to task performance. Future work could examine such effects through analyses that include comparisons of mixed versus single condition block performance as has been done in fMRI studies of task switching to parse out neural activity associated with transient versus sustained modulations in control-related activations (Braver, Reynolds, & Donaldson, 2003). In fact, the region of activity over frontocentral recording sites observed during the cue interval in the present study is consistent with Barber and Carter’s (2005) finding of increased bilateral activation of the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex during the preparatory phase of an explicit version of the POP task. Moreover, the time course of the BOLD response reported by Barber and Carter reveals a similar pattern of increased activation (percentage signal change) for nonprepotent responses and decreased activation for prepotent responses.

An advantage to using probability cues in the present study is that it permits an analysis of the response to probes in those cases when the anticipated stimulus– response strategy is incongruent with the current probe. One might posit that any reasonable theory of cognitive control would predict that this incongruency would elicit an increase in cognitive control given the need to reconfigure the so-called task set once the probe appeared. However, whereas induced gamma power was increased for these incongruent trials relative to congruent trials in which the probe identity matched expectation, this difference appears to have been driven by a marked reduction of gamma-band activity in congruent trials. We contend that this somewhat counterintuitive result possibly reflects the role that gamma-band activity may play in the actualization of an established task set. Consistent with the finding of increased parietal gamma-band activity for high- versus low-control trials in the present task, there is evidence that activity in the medial superior parietal lobule is associated with the domain-general task set configuration (Esterman, Chiu, Tamber-Rosenau, & Yantis, 2009) and that parietal gamma-band activity encodes motor goals during a pro-/anti- saccade task (Van der Werf, Jensen, Fries, & Medendorp, 2008).

However, the present data suggest that gamma-band activity in this region was modulated by expectancies regarding the identity of the probe, being suppressed on those occasions when the task indicated by the color of the probe stimulus was congruent with the most likely task set indicated by the probability cue rather than increased for incongruent probes. Such findings are consistent with previous findings of decreased power and synchrony in the gamma band that have been observed between 200 msec and 450 msec in the no-go condition of a go/no-go task, which has been taken to indicate a connection between the gamma-band activity and transition to motor preparation (Harmony, Alba, Marroquin, & Gonzalez-Frankenberger, 2009; Rodriguez et al., 1999).

This interpretation, relating suppression of induced gamma to the transition between task-relevant cognitive operations and motor preparation, may also explain the pattern of results seen over the right frontal electrodes during the probe-delay interval. Induced gamma-band power in this region was suppressed to some extent following all probe stimuli, but to a greater extent when the color of the probe matched the expected color, given the cued location. Such congruency between the anticipated task and the probe may have facilitated the transition to motor preparation, leading to increased suppression of induced gamma on those trials. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the modulation of frontal gamma-band activity was more lateralized during the probe interval, given that the lateral premotor cortex is commonly linked with motor preparation and sensory-guided action (Brass & von Cramon, 2002; Deiber et al., 1991). However, these possible interpretations must be made with caution due to the relatively small number of trials (N = 30) in the probe analysis conditions in which each color appeared in an unexpected location. This limitation does not pose a problem for the interpretation of the analysis of the cue–probe interval for which the study was designed and for which there was ample sampling per condition (N = 200). Future studies could more adequately sample probe period activity to examine how gamma activity modulates with cognitive control and motor preparatory processes.

One possible caveat to the interpretation of the present cue period findings is the concern that induced gamma-band activity has been related to the planning and execution of saccadic eye movements (Jerbi et al., 2009; Reva & Aftanas, 2004; Trujillo, Peterson, Kaszniak, & Allen, 2005). For example, Yuval-Greenberg, Tomer, Keren, Nelken, and Deouell (2008) presented evidence that transient modulations of the induced gamma-band response can be tightly time-locked with saccades and Trujillo et al. demonstrated that the saccadic gamma-band response can even be sensitive to experimental conditions. However, concerns that saccade-related gamma-band activity may have served as a confounding signal in the EEG analyses are assuaged by several aspects of the present findings.

We first note that there likely was saccade-related gamma activity indexed by the periocular channels. The modulations there were broadband in frequency content and peaked at 200 msec postcue onset, both features consistent with miniature saccadic activity (Yuval-Greenberg et al., 2008). However, this can be contrasted with a number of features regarding the frontal and parietal channel findings. First, the topography itself is suggestive of dissociations. Although the parietal modulations could be due to posteriorly oriented projections of the saccade-related gamma, one would expect spatial contiguity of modulations in frontal sites. However, the right frontal activations are clearly spatially dissociated from the periocular activations. Second, the time course appears significantly different, with the frontal and parietal activations being much more temporally extended across most of the cue–probe interval. Finally, the directionality of findings across the regions is strongly suggestive of dissociability of the respective signals. Whereas the periocular signal positively modulates for both the redEX and greenEX cues, the greenEX signal negatively modulates in the frontal and parietal areas. So, although we cannot definitively rule out covariations in the redEX modulations across the regions, the pattern of modulations across conditions is consistent with task-related components of the frontal and parietal activations being dissociable from saccade-related signals. Together, the timing, distribution, and directionality of findings suggest that although saccade-related gamma is detectable in periocular channels, it does not confound interpretations of the frontal and parietal EEG findings.

One surprising aspect of the behavioral results was that accuracy was improved on those trials in which the probe color was “unexpected.” This is a surprising result because one might expect that the now-inappropriate response strategy prepared during the cue–probe interval might lead to an increase in the probability of making an erroneous response. Likewise, such trials should require a task switch as participants negotiate the two response strategies, leading to increased error rates (Monsell, 2003). One potential explanation is that the high level of cognitive control elicited by unexpected probe stimuli elicited a strategic postponement of response execution that permitted improved processing and classification of the probe stimulus. Although studies of task switching commonly manipulate the cue–probe interval, the impact of a task switch following the presentation of a probe stimulus has not been elucidated. Another possible explanation is that responses to colored arrows in the expected locations relied primarily on implicit expectancies and automatic processes, which are more error prone than the explicit processes elicited in those cases in which the color of the arrow did not match expectancy.

Taken together, the present findings provide support to the claim that elevated power in the gamma frequency range indexes the preparation and implementation of cognitive control. Importantly, the use of implicit probability cues addresses the concern that differences between high-and low-control conditions previously reported may correspond with differences between the rules participants are explicitly asked to use. Moreover, despite indications in the literature that saccadic activity may contribute to gamma-band dynamics, the equivalency between conditions in the present task helps to reconcile these findings with continued efforts to determine the relationships between synchronous cortical gamma-band oscillatory activity and cognitive control.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grant 5T32MH018273 (to P.D.K.) and by NIH Grant K08 MH080329 and Astra-Zeneca/APIRE, NARSAD Grant P50 MH084053 (to R.Y.C.).

Footnotes

Frequency bands in the delta (1–2 Hz), theta (3–7 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), and beta (13–29 Hz) ranges were also analyzed; task-relevant modulation was only significant for the gamma (30–80 Hz) band.

Contributor Information

Paul D. Kieffaber, Email: pdkieffaber@wm.edu, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Raymond Y. Cho, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

REFERENCES

- Barber A, Carter C. Cognitive control involved in overcoming prepotent response tendencies and switching between tasks. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:899–912. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M, Braver T, Barch D, Carter C, Cohen J. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review. 2001;108:624–652. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brass M, von Cramon DY. The role of the frontal cortex in task preparation. Cerebral Cortex. 2002;12:908–914. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.9.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver T, Reynolds J, Donaldson D. Neural mechanisms of transient and sustained cognitive control during task switching. Neuron. 2003;39:713–726. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00466-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho RY, Konecky RO, Carter C. Impairments in frontal cortical gamma synchrony and cognitive control in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:19878–19883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609440103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Barch D, Carter C, Servan-Schreiber D. Context-processing deficits in schizophrenia: Converging evidence from three theoretically motivated cognitive tasks. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:120–133. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MX, van Gaal S, Ridderinkhof KR, Lamme VAF. Unconscious errors enhance prefrontal-occipital oscillatory synchrony. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2009;3:54. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.054.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiber MP, Passingham RE, Colebatch JG, Friston KJ, Nixon PD, Frackowiak RSJ. Cortical areas and the selection of movement: A study with positron emission tomography. Experimental Brain Research. 1991;84:393–402. doi: 10.1007/BF00231461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2004;134:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterman M, Chiu Y, Tamber-Rosenau B, Yantis S. Decoding cognitive control in human parietal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:17974–17979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903593106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Byrne J, Worden MS, Guise KG, McCandliss BD, Fossella J, et al. The relation of brain oscillations to attentional networks. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:6197–6206. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1833-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng JJ, Behrmann M. Probability cuing of target location facilitates visual search implicitly in normal participants and patients with hemispatial neglect. Psychological Science. 2002;13:520–525. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CM, Konig P, Engel AK, Singer W. Oscillatory responses in cat visual cortex exhibit inter-columnar synchronization which reflects global stimulus properties. Nature. 1989;338:334–337. doi: 10.1038/338334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmony T, Alba A, Marroquin J, Gonzalez-Frankenberger B. Time-frequency-topographic analysis of induced power and synchrony of EEG signals during a Go/No-Go task. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2009;71:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MW, Rizzuto DS, Caplan JB, Madsen JR, Lisman J, Aschenbrenner-Scheibe R, et al. Gamma oscillations correlate with working memory load in humans. Cerebral Cortex. 2003;13:1369–1374. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerbi K, Freyermuth S, Dalal S, Kahane P, Bertrand O, Berthoz A, et al. Saccade related gamma-band activity in intracerebral EEG: Dissociating neural from ocular muscle activity. Brain Topography. 2009;22:18–23. doi: 10.1007/s10548-009-0078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, Trinath T, Oeltermann A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature. 2001;412:150–157. doi: 10.1038/35084005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AW, III, Cohen JD, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Dissociating the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex in cognitive control. Science. 2000;288:1835–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makeig S, Bell AJ, Jung T-P, Sejnowski TJ. Independent component analysis of electroencephalographic data. Vol. 8. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1996. pp. 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsell S. Task switching. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2003;7:134–140. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mørup M, Hansen LK, Sidse A. ERPWAVELAB: A toolbox for multi-channel analysis of time-frequency transformed event-related potentials. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2007;161:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reva NV, Aftanas LI. The coincidence between late non-phase-locked gamma synchronization response and saccadic eye movements. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2004;51:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez E, George N, Lachaux JP, Martinerie J, Renault B, Varela FJ. Perception’s shadow: Long-distance synchronization of human brain activity. Nature. 1999;397:430–433. doi: 10.1038/17120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, Detwiler M. A connectionist control architecture for working memory. In: Bower G, editor. The psychology of learning and motivation. Vol. 21. New York: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 54–119. [Google Scholar]

- Simon J, Berbaum K. Effect of conflicting cues on information-processing: The Stroop effect vs. the Simon effect. Acta Psychologica. 1990;73:159–170. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(90)90077-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snitz B, Carter C, MacDonald A, Becker T, Stenger V, Cohen JD. Conflict- and error-related activity of the anterior cingulate cortex in medication-naive first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005;31:435. [Google Scholar]

- Tallon-Baudry C, Kreiter A, Bertrand O. Sustained and transient oscillatory responses in the gamma and beta bands in a visual short-term memory task in humans. Visual Neuroscience. 1999;16:449–459. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899163065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tittinen H, Sinkkonen J, Reinikainen K, Alho K, Lavikainen J, Naatanen R. Selective attention enhances the auditory 40-Hz transient response in humans. Nature. 1993;364:59–60. doi: 10.1038/364059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo LT, Peterson MA, Kaszniak AW, Allen JJB. EEG phase synchrony differences across visual perception conditions may depend on recording and analysis methods. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2005;116:172–189. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Werf J, Jensen O, Fries P, Medendorp W. Gamma-band activity in human posterior parietal cortex encodes the motor goal during delayed prosaccades and antisaccades. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:8397–8405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0630-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuval-Greenberg S, Tomer O, Keren AS, Nelken I, Deouell LY. Transient induced gamma-band response in EEG as a manifestation of miniature saccades. Neuron. 2008;58:429–441. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]