Abstract

Previous research suggests hypoactivity in response to the visual perception of faces in the fusiform gyri and amygdalae of individuals with autism. However, critical questions remain regarding the mechanisms underlying these findings. In particular, to what degree is the hypoactivation accounted for by known differences in the visual scanpaths exhibited by individuals with and without autism in response to faces? Here, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), we report “normalization” of activity in the right fusiform gyrus, but not the amygdalae, when individuals with autism were compelled to perform visual scanpaths that involved fixating upon the eyes of a fearful face. These findings hold important implications for our understanding of social brain dysfunction in autism, theories of the role of the fusiform gyri in face processing, and the design of more effective interventions for autism.

Keywords: Autism, Face Perception, Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Fusiform Gyrus, Amygdala

Autism is a pervasive neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by pathognomic social deficits (Kanner, 1943; Wing & Gould, 1979). A deficit in eye contact is among the most striking of these social impairments and is one of the diagnostic criteria for the disorder (DSM-IV-TR, American Psychiatric Association, 1994). This deficit appears to be among the earliest behavioral manifestations of autism. For example, in a study of first birthday videos, looking at others was found to be among four social behaviors that differentiated children who would go on to be diagnosed with autism later in childhood (Osterling & Dawson, 1994). Eye-tracking studies have served to quantify and characterize the developmental nature of the eye-to-eye gaze impairment (Jones et al., 2008; Klin et al., 2002; Pelphrey et al., 2002). For instance, Jones and his colleagues (2008) measured looking to the eyes of others in two-year-old children with autism (currently the earliest possible point of reliable diagnosis), typically developing children, and developmentally delayed children without autism. They found that looking at the eyes of others was significantly decreased while looking at the mouth was increased in two-year-olds with autism, in comparison with typically developing and developmentally delayed but nonautistic children. Jones and colleagues (2008) concluded that “diminished and aberrant eye contact is a lifelong hallmark of disability” (pg. 946).

Given the natural history of the social deficits in autism, it is not surprising that many of the available functional neuroimaging studies of individuals with autism have examined aspects of the human face processing system (e.g. Critchley et al., 2000; Pierce et al., 2001; Schultz et al., 2000). Hypoactivation of the amygdalae (e.g. Baron-Cohen et al., 1999; Ogai et al., 2003) and the “fusiform face area” (FFA), a region localized to the lateral fusiform gyri (FFG) (e.g. Critchley et al., 2000; Schultz et al., 2000) that is specialized for face perception (Kanwisher, McDermott, & Chun, 1997; Puce, Allison, Asgari, Gore, & McCarthy, 1996), has been observed in participants with autism in comparison to typically developing participants. However, the question of whether or not hypoactivation in these regions is an aspect of the brain phenotype in autism remains an open and widely debated question.

A recent literature search revealed 18 studies of the face processing system in individuals with autism published between 1999 and mid 2009. Of those 18 studies, 15 reported data from the FFG and 12 reported data from the amygdalae. Ten (Critchley et al., 2000; Dalton et al., 2000; Humphreys et al., 2008; Koshino et al., 2008; Hubl et al., 2003; Pelphrey et al., 2007; Pierce et al., 2001; Piggot et al., 2004; Schultz et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2004) out of 15 studies of the FFG reported hypoactivation in participants with autism compared to neurotypical participants, while five reported equivalent FFG activity (Bookheimer et al., 2008; Hadjikhani et al., 2004; Pierce et al., 2004; Pierce & Redcay, 2008; Kleinhans et al., 2009) in participants with and without autism. A particularly elegant study of children with and without autism reported hypoactivation for unfamiliar faces but equivalent activation for familiar and/or highly salient faces (i.e., pictures of the child’s mother) (Pierce & Redcay, 2008). Eight (Ashwin et al., 2007; Baron-Cohen et al., 1999; Bookheimer et al., 2008; Critchley et al., 2000; Pelphrey et al., 2007; Pierce et al., 2004; Pierce et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2004) of 12 studies reported hypoactivation of the amygdalae in participants with autism as compared to typically developing participants. Three reported equivalent amygdalae activity in affected and unaffected individuals (Pierce et al., 2004; Piggot et al., 2004; Kleinhans et al., 2009). One study reported left amygdala hyperactivation (Dalton et al., 2005) in participants with autism relative to typically developing participants.

Potentially critical methodological differences exist between those studies that have reported hypoactivation versus equivalent activity in the FFG. The majority of studies reporting FFG hypoactivation involved free viewing and/or very modest task demands. In contrast, two of the four studies reporting equivalent activation in the FFG constrained the viewing patterns of the participants by placing a fixation cross in the center of the stimulus (e.g., on the bridge of the nose between the eyes) (Hadjikhani et al., 2004; Pierce et al., 2004). Two others reporting equivalent FFG activation involved a relatively demanding face recognition task in the context of upright and inverted faces (Bookheimer et al., 2008; Kleinhans et al., 2009). Finally, Pierce and Redcay (2008) observed equivalent FFG activity in children with and without autism when the children viewed highly familiar and salient pictures of their mothers. It can be argued that the underlying mechanism uniting these studies is a task manipulation that increased visual attention to the face, and particularly the eyes of the faces, either by requiring participants to maintain a fixation placed between the eyes (Hadjikhani et al., 2004; Pierce et al., 2004) (and thereby potentially removing the confound of altered visual scanpaths), by increasing the salience of the face (Pierce & Redcay, 2008), or by increasing the relevance of the core facial features to the task at hand (Bookheimer et al., 2008). Relatedly, Bird and colleagues (2006) reported that individuals with ASD exhibited attentional modulation in the FFG for house but not face stimuli, suggesting impairment in attentional modulation specific to face stimuli.

As the above review illustrates, the state of the literature on the face processing system in individuals with autism is currently quite unsettled. As expressed by Klin (2008), all of the prior studies can be criticized, albeit on different grounds, for the approaches they have taken to the issue of potentially confounding differences in overt visual attention. On the one hand, studies that have involved free viewing can be criticized for ignoring known differences in visual attention in individuals with autism. On the other hand, the two studies that have controlled for differences in visual scanpaths by constraining fixation to a central cross may be criticized because their design does not allow us to evaluate experimentally the exact mechanism underlying the observed outcome. That is, it is possible that constraining visual fixation to the center of the face inadvertently alters the task for the typically developing participants who are forced to attend to a fixation point that, in turn, may reduce their experiences of faces as such. In this circumstance, the observed lack of FFG abnormalities in individuals with autism might actually reflect reduced FFG activation in control participants, rather than increased activity in participants with autism.

Indeed, in a previous study of typically developing individuals, we experimentally investigated this issue via the direct manipulation of visual scanpaths (Morris et al., 2006). Participants visually tracked a small crosshair moving across a single static face for the duration of the experiment. When the crosshair followed an “atypical” scanpath (landing on eyes 12% of the time, or less than that of a normative viewing pattern of a typically developing subject), decreased FFA activation was observed as compared to that recorded during a “typical” scanpath (landing on eyes approximately 80% of the time, or more than that of a typically developing subject). This study demonstrates that by making typically developing individuals scan the eyes less, we can actually reduce levels of FFA activity.

Only one study to date has directly measured visual attention to faces during fMRI scanning. Dalton and colleagues (2005) reported a strong, positive correlation in participants with autism between the number of fixations upon the eyes of faces and the level of activation in the FFG and left amygdala, suggesting a link between visual scanpaths and hypoactivation in these components of the face processing system. This association could mean that individuals with more FFG and left amygdala activity are the ones who look more at the eyes of faces. Alternatively, the correlation could reflect that when participants with autism happen to look more at the eyes, they in turn exhibit greater activity in face processing regions. The available data cannot adjudicate between these two plausible mechanisms because scanpaths were not experimentally manipulated.

In the present study, we sought to manipulate experimentally activity in the face processing system of individuals with autism by compelling them to look at the eyes of faces to varying degrees. This manipulation allowed us to determine whether hypoactivation in the amygdalae and FFG can be accounted for by known differences in the visual scanpaths exhibited by individuals with and without autism in response to faces. We directly manipulated visual scanpaths across three experimental conditions with naturalistic scanpaths involving: free viewing, low, medium, or high amounts of fixating the eyes in a group of high-functioning adults with autism and a matched group of typically developing participants during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

Methods

Participants

We studied a group of 12 adults with autism (mean age = 25.5, 11 male) and 7 typically developing adults (mean age = 28.57, 7 male) matched on age and verbal and performance IQ (see Table 1). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant for a protocol approved by the local Human Investigations Committee. All individuals with autism met DSM-IV criteria for autism as based on a history of clinical diagnosis of autism, expert evaluation, parental interview (ADI-R; Lord et al., 1994), and proband assessment (ADOS-Module 4; Lord et al., 2000). Typically developing individuals completed either the ADOS (n = 3) or the SCQ (Rutter et al., 2003) (n = 4) to ensure they did not meet criteria for a diagnosis of autism. The two groups did not differ significantly on any of the matching variables, including age [t(17) = 1.08, p = .29], verbal IQ [t(17) = 1.86, p = .08], and performance IQ [t(17) = 1.56, p = .14].

Table 1.

Subject demographics and diagnostic scores.

| Autism (N=12) | Typically Developing (N=7) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N male : N female | 11 : 1 | 7 : 0 | ||

| Age range (years) | 18–37 | 22–37 | ||

| RH : LH | 11 : 1 | 7 : 0 | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age | 25.5 | (7.47) | 28.57 | (5.74) |

| Verbal IQ | 106.7 | (11.7) | 114.9 | (4.4) |

| Performance IQ | 102.2 | (15.8) | 112.0 | (6.7) |

| ADI Social | 21.6 | (3.2) | - | - |

| ADI Communication Verbal | 16.5 | (4.1) | - | - |

| ADI Communication Nonverbal | 9.0 | (3.0) | - | - |

| ADI Stereotyped Behaviors | 6.1 | (2.4) | - | - |

| ADOS Communication | 4.8 | (1.2) | 1.0 | (0.8) |

| ADOS Social | 8.5 | (2.8) | 0.3 | (1.3) |

| ADOS Com+Soc Total | 13.3 | (3.8) | 1.3 | (1.6) |

| ADOS Stereotyped Behaviors | 1.4 | (1.3) | 0.0 | (0.7) |

| SCQ | - | - | 3 | (2.8) |

Experimental stimuli

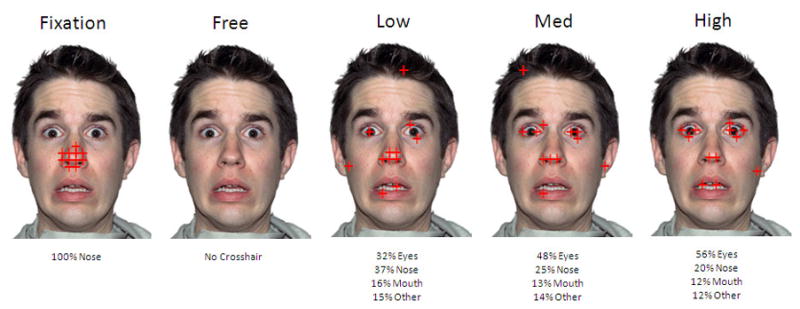

We modified aspects of the basic design of our previous study of typically developing individuals (Morris et al., 2006) to address our current hypotheses. Throughout the experiment, participants viewed a single fearful, male face (shown in Figure 1) in full color from the NimStim set of facial expressions (Tottenham et al., 2009) in the center of the screen. Although the Morris et al. (2006) study used a single neutral face, we chose to maximize the potential for amygdala activation in our participants by asking them to view a fearful face, as fearful faces have been repeatedly shown to be strong activators of the human amygdalae (e.g., Morris et al., 1996). Participants visually followed a small red crosshair as it made small jumps across the face every 500 ms such that they made a saccade and fixated upon the crosshair at each new location.

Figure 1.

Experimental design. Each face image shows fixations from a block condition in which participants’ attention was drawn to the eye area of the emotional face for varying amounts of time. During free viewing, participants were instructed to view the face as they normally would.

As illustrated in Figure 1, three types of 12-s blocks were designed to simulate scanpaths with varying amounts of eye fixation (Low = 32%, Medium = 48%, High = 56%). In contrast to the Morris et al. (2006) study, we selected these particular amounts in an effort to mimic normal variation in the scanpaths typically developing adults make in response to faces. We based the selected values upon eye-tracking results from our recent study of individual differences in visual scanpaths exhibited by typically developing young adults when viewing a fearful face (Perlman, Morris, Vander Wyk, Green, Doyle, & Pelphrey, 2009). We also employed a Free Viewing condition in which participants were allowed to look at the faces as they typically would in the absence of a moving crosshair. Each block (6 blocks of each condition interspersed with each other throughout the experiment) alternated with a Central Fixation block during which the crosshair made small jumps around the nose area for 6 seconds. To ensure compliance with our instructions, participants were asked to press a button upon seeing the rare (two times across the experiment) event of the crosshair changing from red to blue for 500 milliseconds. All of the participants were able to comply with this instruction 100% of the time.

fMRI data acquisition

Scanning was performed on a Siemens 3 Tesla Allegra head-only scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). High-resolution, T1-weighted anatomical images were acquired using an MPRAGE sequence (TR = 1630 ms; TE = 2.48 ms; FOV = 20.4 cm; α = 8°; image matrix = 2562; voxel size = 0.8 × 0.8 × 0.8 mm; 224 slices). Whole-brain functional images were acquired using a single-shot, gradient-recalled echoplanar pulse sequence (TR = 2000 ms; TE = 30 ms; α = 73°; FOV = 20.4 cm; image matrix = 642; voxel size = 3.2 × 3.2 × 3.2 mm; 35 slices) sensitive to blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) contrast. Runs consisted of the acquisition of 225 successive brain volumes beginning with 2 discarded RF excitations to allow for steady-state equilibrium.

Results

We first compared the brain activity of the individuals with and without autism during Free Viewing using an ANOVA with random effects implemented in the Brain Voyager QX software package (Brain Innovation, Maastricht, The Netherlands). In agreement with several previous studies, we found that regions localized to the right lateral FFG and amygdalae were significantly more active in the typically developing participants as compared to individuals with autism during Free Viewing [t(72) ≥ 2.04]. These regions are illustrated in Figure 2. We used the false discovery rate procedure (Genovese, Lazar, & Nichols, 2002) [FDR(q) < .05] to control for multiple statistical comparisons. Using the free viewing condition as a localizer, we created regions of interest (ROIs) derived from this analysis to investigate the influence of our experimental manipulation of scanpaths on activity in areas where participants with autism showed hypoactivation. These ROIs were employed for all subsequent analyses. Following the creation of these ROIs, we set aside the free-viewing data and focused our analyses on the remaining four conditions (Central Fixation, Low, Medium, and High) so as to render the subsequent comparisons orthogonal to our method of identifying ROIs (Kriegeskorte, Simmons, Bellgowan, & Baker, 2009).

Figure 2.

Activation t-map displaying regions in the rFFG (Peak voxel Talairach coordinates: 27x, −55y, −11z), rAMY (18x, −7y, −8z), and lAMY (−24x, −1y, −14z) that were significantly more active in typically developing participants than in participants with autism during Free Viewing.

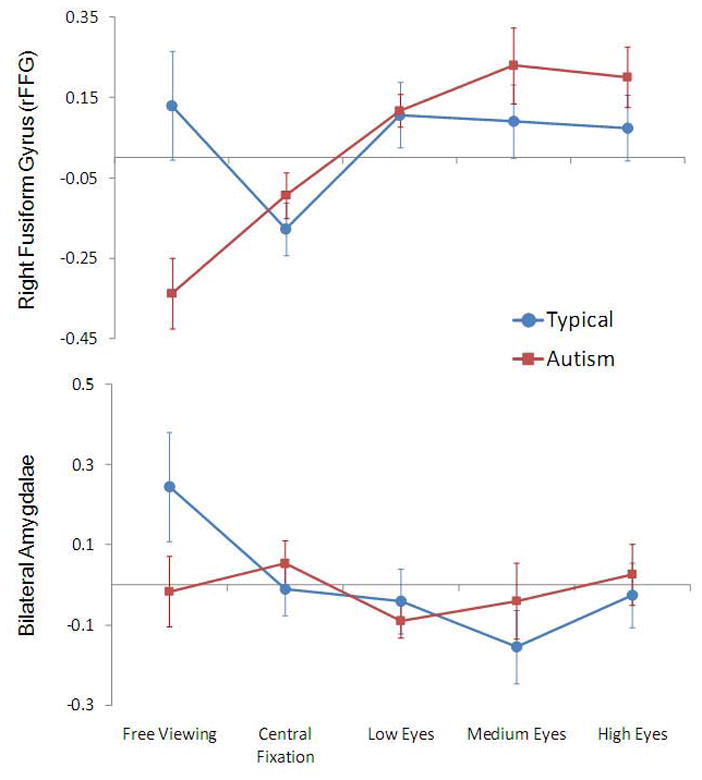

Next, average beta values were extracted by condition for each participant from the ROIs defined in our comparison of individuals with and without autism during free viewing. For the right FFG, we conducted a Group (Autism, Typical) × Condition (Central Fixation, Low, Med, High) repeated-measures ANOVA. This analysis revealed a significant effect of group (Autism > Typical) [F(1,17) = 5.90, p = .02] and a significant effect of condition [F(3,51) = 5.27, p = .003]. The Group × Condition interaction was not significant. Repeated measures comparisons by condition revealed that activity was significantly higher for Low [F(1,17) = 13.37, p = .002], Medium [F(1,17) = 9.22, p = .007], and High Eyes [F(1,17) = 9.05, p = .008] versus Central Fixation. However, activity for Low, Medium, and High Eyes did not significantly differ amongst each other. This pattern of effects is illustrated in the Figure 3 (top panel). Notably, activation in the right FFG from individuals with autism increased from a slightly negative response during central fixation to a robustly positive response for each of the eye fixation conditions.

Figure 3.

Line graphs representing average beta value (across all voxels of the ROI) in the right FFG (top panel) and the bilateral amygdala (bottom panel) for Free Viewing, Central Fixation, Low, Medium, and High Eyes conditions. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

In sharp contrast to the pattern of results obtained for the right FFG, within the amygdalae, a Group (Typical, Autism) × Hemisphere (Left, Right) × Condition (Central Fixation, Low, Med, High) repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant main effects or interactions (Figure 3,bottom panel).

Discussion

By identifying hypoactivation in two components of the face processing system, the FFG and the amygdalae, in people with autism during unrestricted viewing of faces, our results replicate numerous studies (e.g. Critchley et al., 2000; Pierce et al., 2001). Our findings concerning increases in FFG activity when participants with autism are compelled to look at the eyes are generally consistent with the two prior studies that, using varying methodology, constrained fixation to a central crosshair on a face (Hadjikhani et al., 2004; Pierce et al., 2004). However, we demonstrate here that activity in the right FFG of individuals with autism increases from a below zero level during the central fixation condition to robustly positive levels during execution of a scanpath involving eye contact, as it does for typically developing subjects. This increase is directly attributable to our experimental manipulation of looking at the eyes. In essence, by simply manipulating visual attention to the eyes, we were able to “normalize” activity in one component of the face processing system in individuals with autism. Thus, it seems that with encouraging any variation in typically developing scanpath, we were able to raise activity in the right FFG to typically developing levels.

Furthermore, our findings from the free viewing condition (Figure 3, top panel) reveal that the effect is not attributable to decreases in activity in the FFG of our neurotypical participants as a function of artificially constraining their visual scanpaths during the Low, Medium, and High conditions. It is noteworthy that when the fixation patterns were constrained to the center of the face during our Central Fixation condition, as they were constrained to the center of the eyes in the by Hadjikhani et al. (2004) and to the center of the screen by Pierce et al. (2004), we found reduced activity to the point of negative activation in both groups of participants, but this effect was more pronounced for typically developing individuals relative to their free-viewing data.

Our findings have important repercussions for theoretical debates concerning the nature of the FFA. Some researchers have argued that the FFA is not specialized for faces per se; rather, the seemingly selective response to faces reflects the development of a high level of visual “expertise” for faces, relative to other categories of objects, in typically developing individuals (Gauthier et al., 1999; Tarr & Gauthier, 2000). This theoretical camp has seized upon the findings of FFA hypoactivation in autism as evidence in favor of their theory of visual processing (e.g., Grelotti et al., 2002). Specifically, they argue that a lack of attention to the eyes leads to a failure to develop a FFA in individuals with autism. Our results are not easily reconciled with the expertise view of face processing deficits in autism. We do find that the FFA is hypoactive in individuals with autism, but we show here that this hypoactivation can be reversed with a simple manipulation of fixation to the eyes. It appears that an FFA is present in individuals who presumably lack the necessary “expertise” with faces to have developed such a region.

In contrast to the FFG, our manipulation of eye contact had no effect on amygdalae activation in our group of participants with autism. In typically developing individuals, constraining eye movements to the center of the screen or directing eye movements to the eyes of the stimulus face served to greatly decrease amygdalae activity (bottom panel of Figure 3). This observation is consistent with previous research conceptualizing the role of the amygdalae as directing attention towards salient environmental stimuli such as the eyes of faces (e.g., Adolphs et al., 2005). It is possible that we do not observe amygdalae activity when we constrain the eye movements of typically developing participants because we are removing the need for the amygdalae to direct eye movements in response to the presentation of an emotionally expressive faces. In the case of autism, the lack of amygdalae activity during free viewing, combined with the observation that this hypoactivation cannot be reversed via the manipulation of eye movements, suggests that this brain mechanism for directing eye movements to the key, most socially relevant features of a face is severely impaired in individuals with autism.

We must acknowledge an important limitation to our experimental design. Eye-tracking data was not collected during our fMRI scans. Thus, we cannot be certain that our participants made all of the eye movements we wished them to make and only those eye movements, nor can we be sure that participants fixated upon the cross in order to detect color change. Nonetheless, the fact that all participants were able to identify the rare and very subtle instances of the crosshair turning from red to blue with 100% accuracy provides some reassurance that our manipulations, via attention to the crosshair, were successful. In addition, we have no data concerning the scanpaths participants were making during the Free Viewing condition, although, on the basis of prior reports (Jones et al., 2008; Klin et al., 2002; Pelphrey et al., 2002), we suspect that participants with autism were looking less at the eyes then were our typically-developing participants.

A second limitation of our study concerns our relatively small sample size of matched typically developing individuals. It is possible, that our study was underpowered for detecting group differences. We do not, however, believe this to be the case given that our 7 typically developing subjects showed significantly more, rather than less, right FFG and bilateral amygdalae activity during the free viewing condition. Thus, the lack of significant differences between subjects with autism and their typically developing counterparts on all other conditions in which scanpaths were manipulated should reflect the effects of our manipulation.

In summary, the present results add a higher degree of specificity to our understanding of social brain dysfunction in autism. Pivotal questions are raised for future research, however, including the following: If the FFG can be engaged in individuals with autism, why is it not engaged organically, and what limits the implementation of this region in everyday situations? Our results offer important implications for behavioral interventions that may help those with autism to develop higher levels of social functioning through increased attention to the eyes of social partners. The present findings offer some preliminary insights into the mechanisms by which the common clinical practice of encouraging eye contact might serve to shape the development of the social brain. Requiring individuals with autism, even high-functioning adults, to fixate the eyes appears temporarily to “normalize” activity within a previously silent component of the face processing system. Future research will be needed to determine if this kind of manipulation can have any lasting effects on brain activity beyond the time frame of a single experimental session.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the participants in this study who generously gave of their time to make this research possible. We also wish to thank Drs. Ami Klin, Fred Volkmar, and Sarah-Jayne Blakemore for their extremely helpful comments on this manuscript. This research was supported by the NICHD Pittsburgh Autism Center for Excellence and by the John Merck Scholars Fund. Kevin Pelphrey is supported by a career development award from the NIMH.

References

- Ashwin C, Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, O’Riordan M, Bullmore ET. Differential activation of the amygdalae and the ‘social brain’ during fearful face-processing in Asperger syndrome. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Ring HA, Wheelright S, Bullmore ET, Brammer MJ, Simmons A, et al. Social intelligence in the normal and autistic brain: An fMRI study. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:1891–1898. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird G, Catmur C, Silani G, Frith C, Frith U. Attention does not modulate neural responses to social stimuli in autism spectrum disorders. NeuroImage. 2006;31(4):1614–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookheimer SY, Wang AT, Scott A, Sigman M, Dapretto M. Frontal contributions to face processing differences in autism: Evidence from fMRI of inverted face processing. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2008;14:922–932. doi: 10.1017/S135561770808140X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Daly EM, Bullmore ET, Williams SCR, Van Amelsvoort T, Robertson DM, et al. The functional neuroanatomy of social behavior: Changes in cerebral bloodflow when people with autistic disorder process facial expressions. Brain. 2000;123:2203–2212. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.11.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton KM, Nacewicz BM, Johnstone T, Schaefer HS, Gernsbacher MA, Goldsmith HH, et al. Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:519–526. doi: 10.1038/nn1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1992;15:353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier I, Behrmann M, Tarr MJ. Can face recognition really be dissociated from object recognition? Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1999;11:349–370. doi: 10.1162/089892999563472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage. 2002;15:870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grelotti DJ, Gauthier I, Schultz RT. Social interest and the development of cortical face specialization: What autism teaches us about face processing. Developmental Psychobiology. 2002;40:213–225. doi: 10.1002/dev.10028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjikhani N, Joseph RM, Snyder J, Chabris CF, Clark J, Steele S, et al. Activation of the fusiform gyrus when individuals with autism spectrum disorder view faces. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1141–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubl D, Bölte S, Feineis-Matthews S, Lanfermann H, Federspiel A, Strik F, et al. Functional imbalance of visual pathways indicates alternative face processing strategies in autism. Neurology. 2003;61:1232–1237. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000091862.22033.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Hasson U, Avidan G, Minshew N, Behrmann M. Cortical patterns of category-selective activation for faces, places and objects in adults with autism. Autism Research. 2008;1:52–63. doi: 10.1002/aur.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W, Carr K, Klin A. Absence of preferential looking to the eyes of approaching adults predicts level of social disability in 2-year-old toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:946–954. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.8.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. The fusiform face area: A module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17(11):4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans NM, Johnson LC, Richards T, Mahurin R, Greenson J, Dawson G, et al. Reduced neural habituation in the amygdala and social impairments in autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):467–475. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klin A. Three things to remember if you are a functional magnetic resonance imaging researcher of face processing in autism spectrum disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64:549–551. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klin A, Jones W, Schultz RT, Volkmar FR, Cohen DJ. Visual fixation patterns during viewing of naturalistic social situations as predictors of social competence in individuals with autism. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:809–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshino H, Kana RJ, Keller TA, Cherkassky VL, Minshew NJ, Just MA. FMRI Investigation of working memory for faces in autism: Visual coding underconnectivity with frontal areas. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:289–300. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph RM, Ehrman K, McNally R, Keehn B. Affective response to eye contact and face recognition ability in children with ASD. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2008;14:947–955. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708081344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, et al. The autism diagnostic observation schedule–generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism diagnostic interview-revised: A revised version of a daignostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JP, Pelphrey KA, McCarthy G. Controlled scanpath variation alters fusiform face activation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2006;2:31–38. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Frith CD, Perrett DI, Rowland D, Young AW, Calder AJ, et al. A differential neural response in the human amygdala to fearful and happy facial expressions. Nature. 1996;383:812–185. doi: 10.1038/383812a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogai M, Matsumoto H, Suzuki K, Ozawa F, Fukuda R, Uchiyama I, et al. fMRI study of recognition of facial expression in high-functioning autistic patients. NeuroReport. 2003;14:559–563. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200303240-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterling J, Dawson G. Early recognition of children with autism: A study of first birthday home videotapes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:247–257. doi: 10.1007/BF02172225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelphrey KA, Morris JP, McCarthy G, LaBar KS. Perception of dynamic changes in facial affect and identity in autism. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2007;2(2):140–150. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelphrey KA, Sasson NJ, Reznick JS, Paul G, Goldman BD, Piven J. Visual scanning of faces in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;32:249–261. doi: 10.1023/a:1016374617369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman SB, Morris JP, Vander Wyk BC, Green SR, Doyle JL, Pelphrey KA. Individual differences in personality shape how people look at faces. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(6):e5952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, Haist F, Sedaghat F, Courchesne E. The brain response to personally familiar faces in autism: Findings of fusiform activity and beyond. Brain. 2004;127:2703–2716. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, Müller RA, Ambrose J, Allern G, Courchesne E. Face processing occurs outside the fusiform ‘face area’ in autism: Evidence from functional MRI. Brain. 2001;124:2059–2073. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.10.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, Redcay E. Fusiform function in children with an autism spectrum disorder is a matter of ‘who’. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;64:552–560. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggot J, Kwon H, Mobbs D, Blasey C, Lotspeich L, Menon V, et al. Emotional attribution in high-functioning individuals with autistic spectrum disorder: A functional imaging study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):473–480. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA. Can cognitive processes be inferred from neuroimaging data? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2006;10(2):59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puce A, Allison T, Asgari M, Gore JC, McCarthy G. Differential sensitivity of human visual cortex to faces, letterstrings, and textures: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16(16):5205–5215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05205.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Bailey A, Berument SK, Lecouteur A, Lord C, Pickles A. Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz RT, Gauthier I, Klin A, Fulbright RK, Anderson AW, Volkmar F, et al. Abnormal ventral temporal cortical activity during face discrimination among individuals with autism and asperger syndrome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:331–340. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr MJ, Gauthier I. FFA: A flexible fusiform area for subordinate-level visual processing automatized by expertise. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:764–769. doi: 10.1038/77666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Tanaka J, Leon AC, McCarry T, Nurse M, et al. The NimStim set of facial expressions: Judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Research. 2009;168(3):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang AT, Dapretto M, Hariri AR, Sigman M, Bookheimer S. Neural correlates of facial affect processing in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):481–490. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing L, Gould J. Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnormalities in children: Epidemiology and classification. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1979;24:11–29. doi: 10.1007/BF01531288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]