Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the utilization of neurologist providers in the treatment of patients with Parkinson disease (PD) in the United States and determine whether neurologist treatment is associated with improved clinical outcomes.

Methods:

This was a retrospective observational cohort study of Medicare beneficiaries with PD in the year 2002. Multilevel logistic regression was used to determine which patient characteristics predicted neurologist care between 2002 and 2005 and compare the age, race, sex, and comorbidity-adjusted annual risk of skilled nursing facility placement and hip fracture between neurologist- and primary care physician–treated patients with PD. Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine the adjusted 6-year risk of death using incident PD cases, stratified by physician specialty.

Results:

More than 138,000 incident PD cases were identified. Only 58% of patients with PD received neurologist care between 2002 and 2005. Race and sex were significant demographic predictors of neurologist treatment: women (odds ratio [OR] 0.78, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.76–0.80) and nonwhites (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.79–0.87) were less likely to be treated by a neurologist. Neurologist-treated patients were less likely to be placed in a skilled nursing facility (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.77–0.82) and had a lower risk of hip fracture (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.80–0.92) in logistic regression models that included demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic covariates. Neurologist-treated patients also had a lower adjusted likelihood of death (hazard ratio 0.78, 95% CI 0.77–0.79).

Conclusions:

Women and minorities with PD obtain specialist care less often than white men. Neurologist care of patients with PD may be associated with improved selected clinical outcomes and greater survival.

Neurologic disorders are common, and neurologic complaints account for up to 15% of primary care office visits.1–3 Studies of medical trainees and graduates in the United States, Europe, and Asia have reported that medical students and physicians feel less secure in their ability to diagnose and manage neurologic problems.4–7 Unfortunately, primary care training programs may not be able to provide sufficient training in the management of complicated neurodegenerative diseases such as PD. Given the recent Medicare emphasis on quality-based reimbursement and the need to contain growing health care costs, understanding the utilization of neurologic specialty services is critical. Furthermore, demonstrating that neurologist treatment improves outcomes of patients with PD would influence evidence-based practice metrics and highlight the need for health policy measures that support neurology practice and neurologic education.

We examined which demographic, socioeconomic, and physician factors correlate with whether a patient with PD received neurologist care and explored the potential health and social impact of neurologist care by comparing nursing home placement rates by physician specialty. Individuals with PD have a high risk of falls,8 particularly falls with resultant hip fracture.9 We compared hip fracture rates in patients with PD treated by neurologists vs those treated by primary care physicians. Finally, we investigated whether neurologist treatment early in the disease course altered survival. Understanding the short- and long-term health outcomes of these care patterns is vital to improve quality of life of those with PD and minimize avoidable excess health care cost.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

This study was approved by the Human Studies Committee at Washington University School of Medicine.

Study population.

The study population consisted of 100% Medicare part A and B outpatient and carrier claims data from the year 2002 from which International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9) code 332.0 was used to identify Medicare beneficiaries with a PD diagnosis seen in an outpatient clinical setting. Medicare is a government-financed health insurance program for the elderly and disabled in the United States, used by 98% of Americans older than age 65. We identified incident cases using previously described methods.10 All patients included in this analysis had at least 2 claims for PD. We excluded those who had subsequent diagnostic claims for secondary parkinsonism or an atypical parkinsonian syndrome. Demographic (race, age, and sex) and residential (county and zip code) data were extracted for each subject. The presence of a diagnostic claim for diabetes, dementia, malignancy (lung, colon/rectum, breast, prostate, or uterine), ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke/TIA, acute myocardial infarction, chronic kidney disease, or congestive heart failure was used to calculate an age-weighted modified Charlson comorbidity index for each subject.11

Community and socioeconomic variables.

Although previous studies of the impact of community and socioeconomic factors on access to specialist treatment in people with PD are uncommon, studies of referral and treatment patterns in people with cancers have demonstrated that neighborhood social and economic factors affect the level of care sought and quality of care received.12–14 We applied a previously developed county-level socioeconomic deprivation score, composed of census data on education (% with high school education), employment (% population unemployed), and poverty (% population living in a crowded house, % population without a car, % population without a telephone, and % population below the federal poverty rate), weighted to reflect the neighborhood factors that affect access to specialty care.15

Physician encounter and referral patterns.

Medicare provider specialty codes identified the physician specialty for each patient encounter. We restricted analysis to patients with PD who had claims generated by physicians specializing in neurology, internal medicine, family practice, or geriatric medicine (who accounted for 98% of outpatient and carrier PD claims). We calculated neurologist encounter rates over a 48-month period by examining carrier files for the cohort from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2005 (the only years of data available at the time of this study). Logistic regression with incident cases for the primary analysis was used to determine the odds of receiving neurologist treatment. In a second model, we assessed the effect of race–sex combinations (white male, white female, black male, black female, Hispanic male, Hispanic female, Asian male, and Asian female) on the likelihood of receiving neurologist care. Both models included the following covariates: modified comorbidity index and socioeconomic deprivation.

Health care services utilization and outcome.

Differences in long-term health and health care utilization in PD were determined by extracting data from the Beneficiary Annual Summary File, which provides individual level data on inpatient hospitalization, outpatient physician visits, home health services, and skilled nursing facility (SNF) care. One-year SNF placement rates were calculated for subjects with PD without incident stroke/TIA (a confounding diagnosis that could alter SNF placement and neurologist care rates). We performed logistic regression analyses of SNF placement with physician specialty as the primary effect variable, adjusting for race, age, sex, socioeconomic deprivation, and modified comorbidity index.

Hip fractures and survival.

To investigate whether treatment by a neurologist was associated with differences in clinical outcomes among patients with PD, we compared 1-year risk of hip fracture between neurologist-treated and primary care physician–treated patients with PD. Because race and sex also have been shown to affect baseline hip fracture risk,16 our logistic regression model for this analysis consisted of hip/pelvic fracture as the main effect variable, with race, sex, socioeconomic deprivation, and modified comorbidity index and age as covariates.

For survival analyses, we extracted vital status information for each patient from 2002 to 2008. Cox proportional hazards models were used to compare survival between neurologist- and primary care physician–treated patients with PD, controlling for age at diagnosis, race, socioeconomic deprivation score, and modified comorbidity index. The time-to-event variable was from the beginning of the study period to the date of death (measured in months). The surviving patients were censored at the end of the calendar year 2008.

Statistical analyses.

Means of continuous variables were compared by analysis of variance, and proportions were evaluated using χ2 tests. Primary analyses were performed on incident cases; sensitivity analyses included prevalent PD and atypical parkinsonism cases where appropriate. Logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards coefficients, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI), and survival curves and posterior probabilities were produced using standard methods. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SPSS version 17 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Subject demographics.

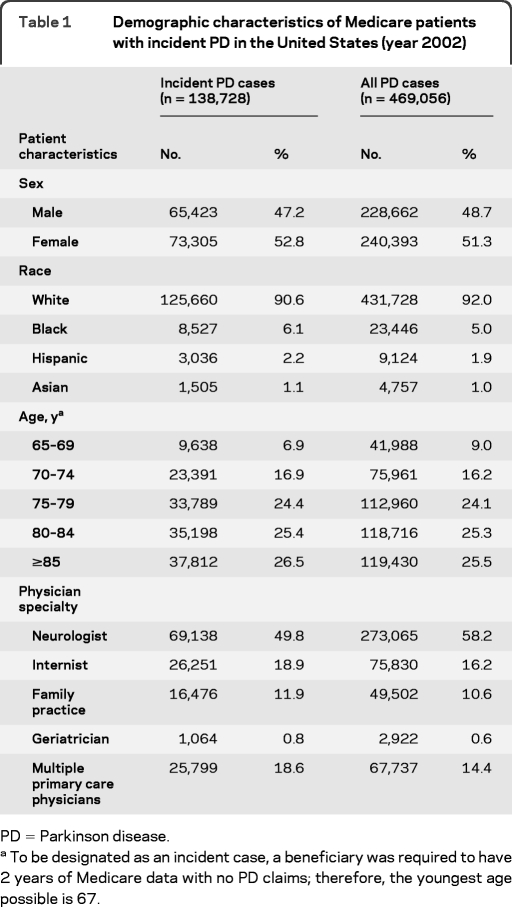

Our analysis included 138,728 Medicare beneficiaries with PD in 2002. The majority of patients with PD in this cohort were white (90.6%); the remaining patients were black (6.1%), Hispanic (2.2%), or Asian (1.1%). Although there were more women living with PD, the age-adjusted incidence of PD was greater in men (537.36 per 100,000) than in women (367.70 per 100,000), consistent with previous data.10 Study population demographic characteristics are summarized in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Medicare patients with incident PD in the United States (year 2002)

PD = Parkinson disease.

To be designated as an incident case, a beneficiary was required to have 2 years of Medicare data with no PD claims; therefore, the youngest age possible is 67.

Predictors of specialist care.

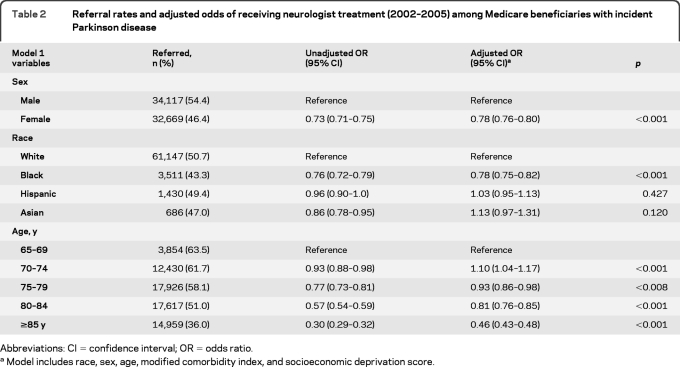

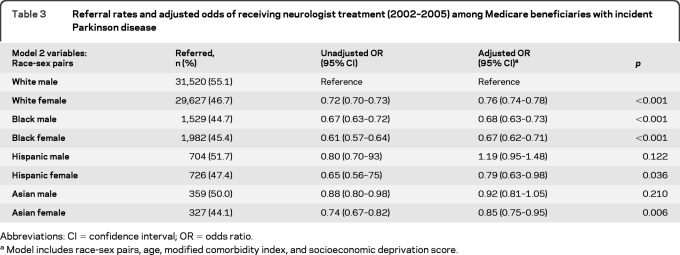

Only 58% of patients with PD saw a neurologist at any time in the 48-month study period. The remaining subjects received their PD care from a primary care physician specializing in internal medicine (18.9%), family practice (11.9%), or geriatric medicine (0.8%). Some subjects (18.6%) had more than one type of primary care physician submit a PD treatment claim on their behalf. A logistic regression model including age, race, sex, modified comorbidity index, and socioeconomic deprivation score revealed that women (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.76–0.80) and nonwhites (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.79–0.87) were less likely to have specialist care. Specific race, sex, and age group data are presented in table 2. A multivariable regression model assessing the interaction of race and sex demonstrated that both factors strongly predicted whether a patient with PD received specialist care. Black female patients with PD were least likely to receive care by a neurologist in the study period (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.62–0.71), followed by black male and white female patients (table 3). Adjustment for comorbidity and socioeconomic variables did not alter race/sex relationships significantly, suggesting that race and sex are major predictors of specialist referral, after accounting for age. A sensitivity analysis using prevalent cases (n = 469,056) and the same covariates supported our findings with incident cases: women (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.77–0.79) and blacks (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.57–0.60) were less likely to have neurologist care, suggesting that referral was not merely delayed in early disease for these groups.

Table 2.

Referral rates and adjusted odds of receiving neurologist treatment (2002–2005) among Medicare beneficiaries with incident Parkinson disease

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; OR=odds ratio.

Model includes race, sex, age, modified comorbidity index, and socioeconomic deprivation score.

Table 3.

Referral rates and adjusted odds of receiving neurologist treatment (2002–2005) among Medicare beneficiaries with incident Parkinson disease

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; OR=odds ratio.

Model includes race-sex pairs, age, modified comorbidity index, and socioeconomic deprivation score.

Health care utilization and outcomes.

In a subgroup of 124,173 Medicare beneficiaries with a claims diagnosis of PD but without incident stroke/TIA, those cared for by a neurologist had the lowest 1-year SNF placement rates compared with patients cared for by all types of primary care physicians (18.0%). The highest SNF rate was among those seen by geriatricians (31.5%), followed by internists (24.1%) and then family practice physicians (21.1%) (χ2; p for difference < 0.001). In a logistic regression model that adjusted for age, race, sex, comorbidity index, and socioeconomic deprivation, patients with PD who received neurologist care were less likely to be placed in a SNF (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.77–0.82; unadjusted OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.75–0.79). In an analysis of all incident cases of PD, treatment by a neurologist was associated with a lower likelihood of hip fracture (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.80–0.92; unadjusted OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.69–0.78).

Survival.

Patients with incident cases of PD who received neurologist care had improved survival demonstrated by higher survival rates and an increase in posterior probability/odds of survival compared with primary care physician–treated subjects (table 4). Cox proportional hazards models with death as the primary effect variable, adjusting for race, age, sex, socioeconomic deprivation, and modified comorbidity index, revealed that patients with PD treated by neurologists had a lower likelihood of death compared with those receiving PD treatment only by primary care physicians (hazard ratio [HR] 0.78, 95% CI 0.77–0.79; unadjusted HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.69–0.71; p < 0.001) (figure). A sensitivity analysis including the much rarer, but more lethal, atypical parkinsonism diagnoses (ICD-9 code 333.0) did not significantly alter the primary results.

Table 4.

Six-year survival (2002–2008) among patients with incident Parkinson disease according to physician specialty

Physician specialty treatment determined using claims data from 2002 to 2005.

Based on race and sex, regardless of physician specialty.

Given that a subject received neurologist care.

Figure. Survival of Medicare beneficiaries with incident Parkinson disease stratified by treating physician specialty, adjusted for race, age, sex, comorbidity index, and socioeconomic deprivation.

*Physicians in the following specialties: internal medicine, family practice, or geriatric medicine.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated demographic variables important in determining whether patients with PD are evaluated by neurologists and what outcome variables are associated with treatment by neurologists. Our data demonstrate that many people diagnosed with PD do not see a neurologist. We also found that race and sex were major determinants of whether patients with PD were treated by a neurologist, even after adjustment for comorbid disease and socioeconomic barriers to specialty care. A major strength of our study is the large sample size and a design that linked otherwise separate census, geographic, health care utilization, and diagnostic administrative datasets. Our study investigated minority (Asian, Hispanic, and African American) patients, who have been largely absent from previous PD epidemiology studies, and suggests disparate care patterns in PD treatment. Should our outcomes and survival data be confirmed using individual level data, measures to lessen these disparities are vital. However, the finding that fewer women and nonwhites receive neurology care may have broader implications than health care disparity. In addition to the clear social and policy implications of our research, these data are important for PD researchers. PD epidemiology studies and treatment trials typically rely on specialty (neurologist or movement disorders neurologist) centers for case identification and recruitment. Our data suggest that this practice may produce a significant referral bias, which is critical in performance of gene or environmental risk studies, and may result in a distortion of PD literature. Furthermore, the exclusive use of specialty center patient populations for recruitment in clinical trials may also propagate a treatment bias, resulting in fewer women and minorities receiving state-of-the-art care.

There are several possible reasons that women, some minorities, and most elderly individuals receive neurologist care less frequently than younger white male patients. Complicated presentations of PD such as prominent gait impairment and postural instability may predominate in some demographic subgroups. This may make referral to a neurologist for treatment more or less likely. Likewise, PD comorbidities such as psychosis or orthostatic hypotension may also play an important role in disproportionate referral to neurologists. In addition, female patients with PD or their spouses may not request specialist care as frequently as male patients or the spouses of male patients with PD. Although 83% of Americans older than age 65 are retired,17 men are traditionally more likely to be wage earners, and, therefore, a need to preserve work function that favors men may exist. Because studies focused on the clinical manifestations of PD in women and minorities are rare, the patient characteristics that predict neurologist care warrant further study. It is unclear whether the finding of decreasing neurologist referral with age represents a confounder or an age disparity.

A second important finding of this study was that neurologist treatment was associated with reduced SNF placement in patients with PD. SNF placement is not an ideal indicator of disease severity, but this may be an important time point in the lifetime of patients with PD. Although we adjusted for age, race, sex, comorbidities, and socioeconomic variables in our assessment of SNF placement, religious, political, or other community variables not assessed in our study may explain a portion of the results obtained. Most patients with PD do not require SNF care, thereby limiting the data available to define an endpoint of progression of advanced PD. Ideally, more precise measures of PD progression, measured longitudinally, would permit a better estimate of the effect of neurologist care disease outcomes.

In addition to the reduction in SNF placement, we found reduced risk of hip fracture in neurologist-treated patients with PD. More severe disease, manifested as greater immobility or postural stability, may result in a bias toward neurologist referral and an underestimation of the benefits of neurologist care. Although unknown confounders may explain these findings, we did control for known risk factors for hip fractures such as sex, race, and age. The impact of even a modest increase in fall rates in patients with PD can have a substantial economic impact on the health care system. According to recent studies, the per person 1-year direct cost of a hip fracture is between $15,000 and $26,000, not including physician fees.18 Of course, the social benefit to those with PD and their families of decreased or delayed need for nursing home placement or avoidance of hip/pelvic fracture is immeasurable. As the aged population at risk for PD continues to increase, the treatment and patient outcome disparities presented, if confirmed, will increase steadily.

Perhaps the most intriguing finding of this study is improved 6-year survival associated with neurologist care in incident PD. There are many potential reasons that neurologist-treated patients with PD may have a better outcome than primary care physician–treated patients with PD. The focused training on neurologic disease during residency and accumulated clinical experience with PD probably improve patient outcomes. In addition, neurologists are probably more likely to be more aggressive with use of medications such as levodopa. Some formularies use Physicians' Desk Reference maximums in establishing maximum covered doses of levodopa. Neurologists are probably more likely to push beyond these dose maximums given their experience with the disease. Although the impact of levodopa use on PD survival is not known, there is a clear dose-dependent improvement in PD motor scores with levodopa.19,20 More aggressive treatment may be associated with a lower incidence of medical conditions caused or exacerbated by immobility, such as venous stasis, pneumonia, and deconditioning. Appropriate use of ancillary PD medications such as dopamine agonists,21,22 catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors,23,24 or selective monoamine oxidase B inhibitors25,26 may also be a factor in improved patient outcomes associated with neurologist care. Finally, neurologists may be more successful in the early recognition and management of common PD-associated comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, psychosis, and dysautonomia. Further study is essential to determine which factors are responsible for improved PD outcomes associated with neurologist care. Moreover, a more systematic approach to education of primary care physicians on basic management of patients with PD may improve disease outcome.

There are several limitations to this study. Diagnosis of PD as “falls” or “tremor” by a primary care physician may have affected the baseline patient demographics. Our data are consistent with other studies, suggesting that PD is much more common in whites than in other racial groups.27–29 However, it is possible that unknown medical, social, economic, or cultural factors may have influenced the observed health care patterns in women, Asians, blacks, or Hispanics. Misdiagnosis of essential tremor as PD by primary care physicians may have increased the proportion of patients with milder cases treated by primary care physicians, and we cannot account for physician accuracy in diagnosis or coding. However, these phenomena would probably bias our data toward the null hypothesis of no difference in outcome or survival. Seeking neurologist care may be more likely in those who are health conscious and may correlate with other behaviors that would improve survival, such as medication compliance and exercise. Our study design used administratively identified cases, and this approach does not provide information on PD severity. Confounding by disease severity could result in either an overestimate or underestimate of the benefit from neurologist care. For example, a severely disabled or bedbound patient may be less likely to see a neurologist. Adjustment with a comorbidity index and restriction of analyses to noninstitutionalized incident cases may not be sufficient. We adjusted for community level socioeconomic factors in our analyses; however, we did not have individual level socioeconomic data. Therefore, there may be individual or group level confounders, both known and unknown, that we could not control. Although this concern does not invalidate our findings, it suggests that these preliminary data be interpreted with caution. Traditional PD outcome measures such as motor function or fall frequency are of interest but were impossible to assess in a large administrative database study.

We present evidence that there are ethnic and gender disparities in the utilization of neurologist care by patients with PD and that neurologist treatment is associated with improved patient outcomes, including survival. Although a formal cost-effectiveness analysis was beyond the scope of this article, the potential health care savings from simply referring patients with PD to a neurologist could be substantial. If the improved clinical outcomes and survival are confirmed in future studies, consistent neurologist care and increased neurologic education at all levels of medical training could emerge as significant disease-modifying measures.

GLOSSARY

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision

- OR

odds ratio

- PD

Parkinson disease

- SNF

skilled nursing facility

Footnotes

Editorial, page 814

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Willis: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, and statistical analysis. Dr. Schootman: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, and statistical analysis. Dr. Evanoff: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, and study supervision. Dr. Perlmutter: drafting/revising the manuscript. Dr. Racette: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, study supervision, and obtaining funding.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Willis receives research support from the NIH, the American Parkinson Disease Association, St. Louis Chapter, Walter and Connie Donius, and the Robert Renschen Fund. Dr. Schootman receives support from the NIH. Dr. Evanoff has served as a consultant for Monsanto and Concentra Health Care and receives research support from the NIH. Dr. Perlmutter serves on scientific advisory boards for the American Parkinson Disease Association, Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, MO Chapter of the Dystonia Medical Research Fund, Greater St. Louis Chapter of the APDA; serves on the editorial board of Neurology®; has received funding for travel from Ceregene; received honoraria from Parkinson Disease Study Group for grant reviews; received partial fellowship support for fellows from Medtronic, Inc.; receives research support from the NIH (NCRR), the Huntington Disease Society of American Center of Excellence, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, HiQ Foundation, McDonnell Center for Higher Brain Function, Greater St. Louis Chapter of the American Parkinson Disease Association, American Parkinson Disease Association, Bander Foundation for Medical Ethics and Advanced PD Research Center at Washington University, and the Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation; and has served as a consultant in medico-legal cases. Dr. Racette receives/has received research support from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Eisai Inc., Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., SCHWARZ PHARMA, Solstice Neurosciences, Inc., Allergan, Inc., NeuroGen (PI), the NIH (NIEHS), BJHF/ICTS, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation; and has served as a consultant in medico-legal cases.

REFERENCES

- 1. Coeytaux RR, Linville JC. Chronic daily headache in a primary care population: prevalence and headache impact test scores. Headache 2007;47:7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacDonald BK, Cockerell OC, Sander JW, Shorvon SD. The incidence and lifetime prevalence of neurological disorders in a prospective community-based study in the UK. Brain 2000;123:665–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maarsingh OR, Dros J, Schellevis FG, van Weert HC, Bindels PJ, Horst HE. Dizziness reported by elderly patients in family practice: prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristics. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flanagan E, Walsh C, Tubridy N. ‘Neurophobia': attitudes of medical students and doctors in Ireland to neurological teaching. Eur J Neurol 2007;14:1109–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jozefowicz RF. Neurophobia: the fear of neurology among medical students. Arch Neurol 1994;51:328–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ridsdale L, Massey R, Clark L. Preventing neurophobia in medical students, and so future doctors. Pract Neurol 2007;7:116–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zinchuk AV, Flanagan EP, Tubridy NJ, Miller WA, McCullough LD. Attitudes of US medical trainees towards neurology education: “neurophobia”: a global issue. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wood BH, Bilclough JA, Bowron A, Walker RW. Incidence and prediction of falls in Parkinson's disease: a prospective multidisciplinary study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;72:721–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grisso JA, Kelsey JL, Strom BL, et al. Risk factors for falls as a cause of hip fracture in women: the Northeast Hip Fracture Study Group. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1326–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wright Willis A, Evanoff BA, Lian M, Criswell SR, Racette BA. Geographic and ethnic variation in Parkinson disease: a population-based study of US Medicare beneficiaries. Neuroepidemiology 2010;34:143–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mukherjee D, Kosztowski T, Zaidi HA, et al. Disparities in access to pediatric neurooncological surgery in the United States. Pediatrics 2009;124:e688–e696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hayanga AJ, Waljee AK, Kaiser HE, Chang DC, Morris AM. Racial clustering and access to colorectal surgeons, gastroenterologists, and radiation oncologists by African Americans and Asian Americans in the United States: a county-level data analysis. Arch Surg 2009;144:532–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schootman M, Lian M, Deshpande AD, et al. Temporal trends in area socioeconomic disparities in breast-cancer incidence and mortality, 1988–2005. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010;122:533–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schootman M, Lian M, Deshpande AD, et al. Temporal trends in area socioeconomic disparities in breast-cancer incidence and mortality, 1988–2005. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010;122:533–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA 2009;302:1573–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. US Census Bureau Labor statistics. 2011. www.bls.gov Accessed in August 2011

- 18. Shi N, Foley K, Lenhart G, Badamgarav E. Direct healthcare costs of hip, vertebral, and non-hip, non-vertebral fractures. Bone 2009;45:1084–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fahn S. Does levodopa slow or hasten the rate of progression of Parkinson's disease? J Neurol 2005;252(suppl 4):IV37–IV42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hauser RA, Auinger P, Oakes D. Levodopa response in early Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2009;24:2328–2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mizuno Y, Abe T, Hasegawa K, et al. Ropinirole is effective on motor function when used as an adjunct to levodopa in Parkinson's disease: STRONG study. Mov Disord 2007;22:1860–1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pinter MM, Pogarell O, Oertel WH. Efficacy, safety, and tolerance of the non-ergoline dopamine agonist pramipexole in the treatment of advanced Parkinson's disease: a double blind, placebo controlled, randomised, multicentre study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:436–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rinne UK, Larsen JP, Siden A, Worm-Petersen J. Entacapone enhances the response to levodopa in parkinsonian patients with motor fluctuations: Nomecomt Study Group. Neurology 1998;51:1309–1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts JW, Cora-Locatelli G, Bravi D, Amantea MA, Mouradian MM, Chase TN. Catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitor tolcapone prolongs levodopa/carbidopa action in parkinsonian patients. Neurology 1993;43:2685–2688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waters CH, Sethi KD, Hauser RA, Molho E, Bertoni JM. Zydis selegiline reduces off time in Parkinson's disease patients with motor fluctuations: a 3-month, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord 2004;19:426–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of rasagiline in levodopa-treated patients with Parkinson disease and motor fluctuations: the PRESTO study. Arch Neurol 2005;62:241–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hemming JP, Gruber-Baldini AL, Anderson KE, et al. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in Parkinsonism. Arch Neurol 2010;68:498–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sethi KD, Meador KJ, Loring D, Meador MP. Neuroepidemiology of Parkinson's disease: analysis of mortality data for the U.S.A. and Georgia. Int J Neurosci 1989;46:87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kurtzke JF, Goldberg ID. Parkinsonism death rates by race, sex, and geography. Neurology 1988;38:1558–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]