Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the links between coping, disability, and mental health among adults who are confronted with age-related vision loss. Drawing on the model of assimilative and accommodative coping (e.g., Brandtstädter, 1999), hierarchical regressions were designed to examine the effects of coping and disability on mental health. Participants were 55 middle-aged and 52 older adults who had been recruited from a community-based rehabilitation agency. Findings demonstrate a critical role of accommodative coping for adaptation, with beneficial effects on mental health that were more pronounced in the case of high disability for younger participants. Finally, findings suggest that dealing with disability may pose more of a mental health risk in middle than in late adulthood.

Being confronted with the implications of functional impairment in middle or late adulthood constitutes a critical adaptational challenge that can put a person at risk for subsequent mental health problems. Age-related vision loss has been identified as the second most common disability among middle-aged and older adults (NCHS, 1993). Its negative impact on functional ability and social activities has been shown to put individuals at risk for depression and poorer perceived life quality (Horowitz & Reinhardt, 2000). Although preliminary evidence based on the model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) shows that coping is a key factor in adaptation to vision loss, this research has contributed more to identifying maladaptive patterns of coping than to learning what may be adaptive (e.g., Brennan, et al., 2001). However, optimal interventions depend as much on knowing about coping styles that are adaptive as on understanding what may increase risk for poor mental health. Furthermore, because only few studies have included a developmental perspective, this research has been mostly limited to the study of older adults.

The present study sought to fill this gap by including both middle-aged and older adults, and by applying the model of assimilative and accommodative coping (Brandtstädter, 1999; Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002), a theoretical framework that incorporates a developmental component, and specifies coping tendencies that mitigate depression, enabling a person to positively adjust to the experience of major decline. The insights gained from this study can guide subsequent research that serves to identify those who are at risk for mental health problems, and to optimize interventions that help individuals adapt to vision impairment as well as to other disabilities.

Prevalence and Characteristics of Age-Related Vision Impairment

Age-related vision impairment affects 13.8 million Americans 45 years and older, and its prevalence increases with age (NCHS, 1993). Reported percentages range from 15% of Americans aged 45–64 years, 17% aged 65–74, and 26% aged 75 and older (The Lighthouse Inc., 1995). The most common age-related eye diseases (e.g., macular degeneration, glaucoma) are characterized by a gradual and continual deterioration. Although complete blindness is relatively rare (Faye, 2000), this vision loss increasingly affects an individual’s functional ability and interaction with the physical and social environment (e.g., Wahl & Oswald, 2000). This negative impact on a person’s daily functioning can have critical mental health consequences. There is strong evidence from a number of studies demonstrating that the experience of chronic vision impairment is linked to depression and the perception of diminished life quality (e.g., Carabellese et al, 1993; Horowitz, Reinhardt, Boerner, & Travis, in press; Karlsson, 1998). In fact, several studies suggest that approximately one-third of older adults who are visually impaired experience clinically significant depressive symptomatology (Horowitz & Reinhardt, 2000). Consistent relationships have been documented between age-related vision loss and lower morale, social isolation problems, affective disorders, and reduced feelings of self worth (e.g., Bazargan & Hamm-Baugh, 1995; Wahl & Oswald, 2000). Furthermore, vision loss is often feared more than other age-related physical impairments because it tends to be associated with a state of complete dependency and helplessness (National Society for the Prevention of Blindness, 2000).

Coping with Vision Loss

While research evidence demonstrates that vision impairment is often related to poor adaptation, there is still great variability among individuals in the extent to which vision impairment results in mental health problems. Prior work has documented differential adaptation to visual impairment depending on factors such as functional disability, social support, and spirituality (Brennan, 2002; Horowitz, et al., in press; Reinhardt, 1996, 2001). However, most relevant to the focus of this study is prior work, which has documented that adaptation to visual impairment is critically affected by personal coping resources (e.g., Brennan & Silverstone, 2000). Research on coping with age-related vision loss has mainly relied on the Stress and Coping model of Lazarus and Folkman (e.g., Benn & Reinhardt, 1999), which distinguishes a problem-focused (i.e., alter the problem) and an emotion-focused (i.e., regulate one’s emotional response to the problem) dimension of coping. However, this typology has been challenged with regard to two major points. First, the global definition of emotion-focused coping complicates the discussion about adaptiveness of coping because it encompasses coping strategies that are not only different in nature but also are likely to have different implications (Brandtstädter & Renner, 1990; Zeidner & Saflofske, 1996). For example, the emotion-focused mode includes intentional activities (e.g., using sedatives, or relaxation techniques to regulate emotions) as well as more automatic responses that may be reflected upon retrospectively, but are usually not deliberately chosen (e.g., positive reappraisal of negative events). Second, the authors have not sufficiently specified under which condition each mode will and should be employed (e.g., Silver & Wortman, 1980). Both of these aspects may explain why empirical research using the two coping dimensions has shown weak to moderate relations to negative outcomes, and why there is a lack of consistent evidence supporting their relationship with positive outcomes (Carver & Scheier, 1994).

Several studies on coping with vision loss among older adults found that while strategies from the emotion-focused dimension consistently predicted poor adaptational outcome, the role of problem-focused coping for positive outcome was less clear (Benn, 1997; Benn & Reinhardt, 1999; Horowitz et al., 1994). For example, in a two-year longitudinal study on adaptation to vision loss, Horowitz and colleagues (1994) found that the use of emotion-focused strategies at baseline increased the risk of poorer adjustment on all outcomes (i.e., adaptation to vision loss, life satisfaction, depression, and functional disability) available at the two-year follow up, whereas the use of problem-focused coping at baseline was only related to life satisfaction. Thus, research based on this model has contributed more to the understanding of coping patterns that are problematic rather than coping patterns that enable a person to positively adjust to the challenge of major life stressors (Brennan, et al, 2001; Carver & Scheier, 1994).

Understanding coping processes that are adaptive, however, is critical to the design and optimization of intervention programs. Finally, the Stress and Coping Model does not explicitly include a developmental perspective on coping. It would seem reasonable, however, that when addressing a developmental phenomenon, such as age-related vision loss, a theoretical framework of coping and adaptation that incorporates a developmental component would be important. Consequently, conceptual frameworks that attempt to explain how people adjust to the challenges, constraints, and losses at different points of the life span (e.g., P. B. Baltes & M. M. Baltes, 1990; Brandtstädter & Renner, 1990; Heckhausen, 1997; Lang, Rieckman, & M. M. Baltes, 2002) are particularly germane to the study of adaptation to vision loss in different age groups.

Empirical support for the appropriateness of a life-span theory framework for the study of coping with loss has been provided by Wahl and colleagues. For example, Wahl et al (1999) found that older adults with vision impairment, when compared to the non-visually impaired control group, used more compensatory strategies, such as relying other senses, simplifying daily tasks, or using optical and adaptive devices (e.g., magnifiers or large print material). With a more specific focus, Wahl, Schilling, Becker, and Burmedi (in press) recently applied the lifespan theory of control, examining the use of control strategies among older adults suffering from age-related macular degeneration. Findings demonstrated that selective primary control (investing internal resources such as effort or time to reach a goal) was important for maintaining functional ability, and selective secondary control (cognitions that strengthen commitment towards the goal) for emotional adjustment. While compensatory primary control (using external resources such adaptive devices) was also important for emotional adjustment, compensatory secondary control (reevaluation of or disengagement from goals) did not predict either of the two outcomes. The latter finding is not surprising if one keeps in mind that the participants in this study dealt with an early stage of the disease at a point when they are more likely to invest all coping efforts into maintaining their status quo.

Overall, this evidence underscores the benefit of using a life-span theoretical framework for the topic of adaptation to functional loss. Although the different life-span theories overlap with respect to the basic features that are thought to characterize adaptational processes, they converge only partially. For example, the measure derived from the life-span theory of control (Heckhausen, 1997) was specifically designed to assess control-related behavior and the frequency of its use. However, adaptational processes can also be conceptualized as general response tendencies rather than, on a behavioral level, as concrete day-today strategies. Control strategies may be considered as the behavioral manifestations of general coping tendencies, and, as such, mediators of the latter’s impact on adaptation. In furthering the line of research that applies the life-span framework to coping and adaptation in the context of chronic impairment, the present study seeks to add to the literature by focusing on the role of general coping tendencies in adaptation to vision impairment. Among the life-span theories, the model that most specifically formulates such general coping tendencies has been advanced by Brandtstädter and associates (e.g., Brandtstädter & Renner, 1990; Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002).

Assimilative and Accommodative Modes of Coping

This model proposes two coping tendencies that are thought to mitigate or prevent depression and enable individuals to positively adjust to age-related losses and declines. Both modes have been found to predict high life satisfaction and low depression (Brandtstädter & Renner, 1990). The assimilative mode (tenacious goal pursuit) reflects the persistent effort to actively adjust life circumstances to one’s preferences. In the accommodative mode (flexible goal adjustment), preferences and goals are adjusted to situational constraints.1

In the context of dealing with a visual impairment, critical daily life tasks such as reading can constitute a major challenge. A person with a strong assimilative tendency may be inclined to invest a lot of effort into still being able to read by using all possible tools or devices to accomplish the goal of reading, no matter how much time and energy it takes. However, when vision further declines, this coping direction may become increasingly frustrating. At this point, a person with a more accommodative tendency may more easily switch gears, think about other aspects of life that are also important, remember that other people may be worse off, or come to the conclusion that this is a part of life.

Assimilative and accommodative modes of coping are not seen as mutually exclusive, but as sometimes operating simultaneously. Personal coping tendencies could be reflected in a person’s reporting one mode more than the other, reporting high levels of both, or reporting little usage of both. Apart from the idea of personal coping tendencies, the model also predicts that assimilative processes tend to dominate as long as situations appear changeable, and that accommodative process should be activated when assimilative efforts become ineffective. This assumption is supported by findings demonstrating an age-related increase in accommodative mode of coping. For example, in a cross-sectional study of adults aged 34–63, Brandtstädter and Renner (1990) showed evidence for a gradual shift from an assimilative to an accommodative mode of coping. Heckhausen (1997) found a similar age-related increase in flexible goal adjustment in a sample of adults aged 20 to 85. This increase is interpreted as an adaptive resource that helps maintain a positive developmental perspective despite the increasingly unfavorable gain-loss balance in later life. Specifically, in the face of increasing decline, accommodative processes are thought to help prevent, or reduce severity and duration of depressive problems. Thus, older adults with functional impairments may show more flexibility in terms of readjusting their priorities and goals than middle-age adults because of greater life experience and the “on-time” character of limitations and losses in old age (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 1994; Krueger & Heckhausen, 1993).

Drawing on this theoretical framework, the present study extends prior research by linking vision impairment severity, functional disability, and assimilative and accommodative coping tendencies with two facets of mental health that capture both the impact on perceived daily functioning and depressive symptomatology. Also, the consideration of middle-aged and older adults allows the determination of the extent to which the effect of coping tendencies varies depending on the stage in the life cycle at which adults deal with vision impairment. It was hypothesized that both vision impairment severity and functional disability would be positively related to mental health problems. Assimilative and accommodative modes of coping were expected to be negatively related to mental health problems, even after controlling for vision impairment severity and functional disability. However, this effect was expected to be stronger for the accommodative mode because, ultimately, the ability to reevaluate one’s goals in the light of irreversible situational constraints (e.g., the task of reading becomes increasingly hard to accomplish) should be particularly beneficial with regard to a person’s mental health. Based on findings demonstrating an age-related shift towards accommodative coping in old age (Brandtstädter & Greve, 1994), the effect of the accommodative mode of coping on mental health problems was expected to be stronger among older compared to middle-aged visually impaired adults. Furthermore, because so little is known about the consequences of vision loss for middle-aged adults, the question whether or not the effect of functional disability on mental health would vary depending on age was also explored. Finally, the role of accommodative coping in the context of disability was addressed by exploring if its effect would differ depending on levels of disability and on age.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

Participants were recruited from the pool of applicants at a vision rehabilitation agency in the northeast. Eligibility criteria included age 40 or older, community-dwelling, English-speaking, sufficiently free from hearing and cognitive deficits to participate in a telephone interview, first time applicants for vision rehabilitation services, completed services within the past six months, and onset of vision impairment within the past five years. The study sample (n = 107) was first stratified by age and then randomly selected from a pool of middle-aged (40 to 64 years) and older adults (65+ years). A response rate of 63% was obtained. Participants were interviewed over the telephone for approximately 45–60 minutes. All items and answering categories were read to the participant during the interview.

Participants in the middle-aged group (n = 55) were on average 55 years old (SD = 6.2), whereas the average age in the older group (n = 52) was 81 (SD = 7.6). There were no significant differences between the age groups with regard to gender. Nearly two-thirds of the sample were women (65%). A lack of significant group differences was also found for race and education, with 65% of participant who endorsed being non-Hispanic White, and 80% reporting an educational level of at least High School Graduate. However, as one would expect, participants in the older group were more likely to be widowed (48%) as compared to the middle-aged group (9%), and less likely to be divorced or separated (8% vs. 33%). Also as expected, participants in the older group were more likely to be retired (83%) as compared the middle-aged group (11%). Interesting to note is that while participants in the middle-aged group were more likely to be currently working (17% vs. 4%), they were also more likely to be unemployed (67% vs. 6%).

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

Single items were used to assess participants’ age, gender, race, education, as well as marital and employment status.

Vision Status

Vision Impairment Severity was measured with the 15-item self-report Functional Vision Screening Questionnaire (Horowitz, Teresi, & Cassels, 1991), which assesses the extent to which vision loss causes difficulty in specific functional areas (e.g., difficulty reading labels on medicine bottles). Each item was scored: 0 = no difficulty; 1 = difficulty. Participants were also asked to self-report their eye disease diagnosis (e.g., macular degeneration, glaucoma, or cataract), and the extent to which their vision changed over the past six months.

Vision Rehabilitation Services

Participants were asked whether or not they had received any vision rehabilitation (Yes/No) following their application for services.

Functional Disability was assessed with a modified version of the OARS Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, 1975), which included both personal (7 items) and instrumental (6 items) activities of daily living (α = .89). Items were assessed on a 4-point rating scale, ranging from 1 “no difficulty” to 4 “can’t do without help”. The 13 items were summed to create a total score (range 0–52).

Assimilative and Accommodative Coping Tendencies were measured with the English version of Brandtstädter and Renner’s (1990) Tenacious Goal Pursuit (TGP) and Flexible Goal Adjustment (FGA) Scale. This 30-item scale is a measure of assimilative (tenacious goal pursuit; item example: “When faced with difficulties I usually double my efforts”) and accommodative (flexible goal adjustment; item example: “I adapt quite easily to changes in plans or circumstances”) coping tendencies. Each of these orthogonal dimensions contains 15 items. Respondents indicate to what extent items apply to them on a 5-point Likert-scale, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” (0–4). The Cronbach Alphas for the two scales based on the current sample were .74 for TGP and .80 for FGA.

Mental Health Outcomes

Two dimensions of mental health were assessed: The measure Social Dysfunction (α = .78) is a seven-item subscale from the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28), an abbreviated version of the original GHQ-60. The GHQ-28 has shown comparable reliability and validity, with higher sensitivity and equal specificity than the GHQ-60, and is specifically recommended for the use of individual subscales (Goldberg & Williams, 1988). The social dysfunction subscale assesses perceived efficacy in psychosocial functioning. Items such as “Have you recently been satisfied with the way you have carried out your tasks?”, “Have you recently felt capable of making decisions”, or “Have you recently felt that you are playing a useful part in things?” were assessed on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3), with the answering categories “better than usual”, “same as usual”, “worse than usual”, and “much worse than usual”.

Depressive Symptoms were measured with the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, a reduced version of the original 20-item CES-D (Radloff, 1977). Factor and reliability analyses indicate that scores from this short-version have psychometric properties that are comparable to those of the original (Kohut, Berkman, Evans, & Cornoni-Huntley, 1993). While the suggested answering format for the 10-item CES-D is “Yes/No”, the answering format of the original CES-D was chosen for the present study, in order to maintain consistency with the categories used in the GHQ subscales. Thus, respondents indicated on a 4-point Likert-type scale that ranges from (0) “less than one day” to (3) “5–7 times a week” how often they experienced the symptoms described by the item in the past week (higher score = higher depressive symptomatology). This scale showed a Cronbach Alpha of .83.

Analysis plan

A correlation matrix was computed prior to multivariate analysis in order to examine the interrelationships between all study variables (see Table 1; see also for descriptives of all variables). Because the correlational links of study variables with the two mental health outcomes were so similar, and there had been no specific differential predictions with regard to these outcomes, the variables Depressive Symptoms and Social Dysfunction were combined into one measure of mental health problems (α = .86).

Table 1.

Descriptives and Intercorrelations of Coping Tendencies, Mental Health Outcomes, Sociodemographics, and Health

| Variables | M (SD) or %a | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Assimilative Coping | 32.1 (7.8) | .18 | −.38** | −.21* | −.37** | −.31** | −.04 | .11 | .08 | .19 | −.16 | −.30** | −.21* | .10 |

| 2. Accommodative Coping | 38.2 (7.9) | -- | −.57** | −.25** | −.53** | −.03 | −.03 | .09 | .16 | −.03 | −.12 | −.11 | −.17 | −.06 |

| 3. Depressive Symptoms | 8.3 (6.7) | -- | .56** | .97** | −.06 | .19* | −.18 | −.24 | −.14 | .33** | .28** | .43** | −.01 | |

| 4. Social Dysfunction | 8.1 (2.5) | -- | .75** | −.13 | .09 | −.18 | −.21* | −.11 | .29** | .26 | .31** | −.08 | ||

| 5. Mental Health Problems Variables | 16.4 (8.3) | -- | −.09 | .18 | −.19 | −.25** | −.14 | .35** | .30** | .44** | −.03 | |||

| 6. Age | 67.3 (14.7) | -- | .14 | −.08 | −.19 | −.02 | −.03 | .16 | −.06 | .05 | ||||

| 7. Gender (female) | 65% | -- | −.39** | −.01 | −.06 | −.01 | .09 | .08 | .15 | |||||

| 8. Marital Status (married) | 36% | -- | .11 | .07 | −.11 | −.12 | −.08 | .02 | ||||||

| 9. Employment (employed) | 13% | -- | .23* | −.23* | −.07 | −.30** | .20* | |||||||

| 10. Education | 4.6 (1.5) | -- | −.11 | −.26** | −.21* | −.09 | ||||||||

| 11 Vision Loss Severity | 11.5 (3.4) | -- | .26** | .46** | .04 | |||||||||

| 12. Vision Worse (yes) | 53% | -- | .38** | −.04 | ||||||||||

| 13. Functional Disability | 34.6 (11.9) | -- | −.06 | |||||||||||

| 14. Rehabilitation Use (yes) | 79% | -- |

Note. N = 107.

p < .05;

p < .01.

% = Valid %.

The rationale of variable selection for the multiple regression analysis was largely conceptual in nature, addressing the hypothesized effects of impairment status and coping modes (see hypotheses above) on mental health problems. Selected sociodemographic variables were included to control for basic characteristics that have shown to have an effect either on adaptational outcome in prior research on visually impaired adults (education; Reinhardt, 1996, 2001), or more generally in research on depression (gender, marital status; e.g., Ernst & Angst, 1992; Earle, Smith, Harris, & Longino, 1998). Employment Status was included because the role of employment can be expected to be different for middle-aged compared to older adults. Use of rehabilitation service was included to control for its potential influence on mental health outcome. Because of the hypothesized role of accommodative coping in response to major loss and constraints over the life course (Brandtstädter & Greve, 1994), two-way interaction terms were added to examine if the effect of accommodative coping on mental health becomes more pronounced with older age, and to explore if this effect varies depending on levels of functional disability2. Drawing on the concept of normative versus non-normative developmental challenges (Neugarten, 1976), another two-way interaction term was included to see if the effect of functional disability on mental health varies depending on age. Finally, a three-way interaction of accommodative coping, disability, and age was added to explore if there is an interactive effect of accommodative coping and disability on mental health problems that varies by age.

Findings from the blockwise hierarchical regression analysis are shown in Table 2. The four blocks were entered in the following order: 1) Sociodemographic Characteristics (gender, marital status, employment status, education); 2) Impairment Status (vision loss severity, change in vision, functional disability, and use of rehabilitation services); 3) Coping Tendencies (assimilative and accommodative coping), and 4) Two-way interactions of age and accommodative coping, accommodative coping and functional disability, age and functional disability, and a three-way interaction of accommodative coping, disability, and age. Finally, the 95% confidence intervals for beta-coefficients were computed in order to compare the relative strength of the two coping variables.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression for Mental Health Problems

| B | SE B | Confidence Interval for B | β | ΔR2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Block 1 | .14** | |||||

| Age | −1.63 | .60 | −2.83 | −.44 | −.20** | |

| Gender (female) | 3.36 | 1.24 | .89 | 5.83 | .19** | |

| Marital Status (married) | −.10 | 1.22 | −2.52 | 2.32 | −.01 | |

| Employment (yes) | −2.58 | 1.86 | −6.28 | 1.12 | −.11 | |

| Education | −.07 | .40 | −.85 | .72 | −.01 | |

| Block 2 | .16** | |||||

| Vision Loss Severity | .39 | .19 | .02 | .76 | .16* | |

| Functional Disability | 1.80 | .68 | .05 | 3.15 | .22* | |

| Vision Worse (yes) | .80 | 1.22 | −1.61 | 3.22 | .05 | |

| Rehab Use (yes) | −.71 | 1.39 | −3.48 | 2.06 | −.04 | |

| Block 3 | .25*** | |||||

| Assimilative Coping | −1.59 | .62 | −2.83 | −.35 | −.19* | |

| Accommodative Coping | −3.25 | .58 | −4.41 | −.2.09 | −.39*** | |

| Block 4 | .10*** | |||||

| Accommodative Coping* Age | −.16 | .60 | −1.35 | 1.04 | −.02 | |

| Accommodative Coping* | −2.26 | .70 | −3.66 | −.87 | −.23** | |

| Functional Disability | ||||||

| Functional Disability * Age | −2.15 | .62 | −3.39 | −.91 | −.24** | |

| Accommodative Coping * | 1.48 | .71 | .07 | 2.89 | .15* | |

| Functional Disability* Age | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Total R2 | .64*** | |||||

Note. Listwise N = 105, ΔR2 = R2 Change. Centered values of age, accommodative coping, and functional disability we used for both individual effects and interaction terms.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Results

As hypothesized, participants’ reported level of vision impairment severity and functional disability were positively linked on a bivariate level to both social dysfunction and depressive symptoms (see Table 1). Similarly, those who reported a decline in vision over the past six months were likely to show more mental health problems. The relationships between the two coping modes and mental health outcome were also as expected, significant and negative. While the links of assimilative coping with both outcomes, and of accommodative coping with social dysfunction were similar to prior findings on associations of these coping modes with mental health variables, the link between accommodative coping and depressive symptoms (−.57***) was stronger than previously found (−.31** to −.41**; as reported in Brandtstädter & Renner, 1990).

Results for the hierarchical regression are depicted in Tables 2. In the prediction of mental health problems, the coping modes accounted for 29% of the variance over and above sociodemographics (12%) and impairment status (15%). It is noted that, within the block Impairment Status, functional disability and vision loss severity emerged as significant independent predictors. Most importantly and as hypothesized, however, the two coping modes accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in mental health outcome, even after controlling for sociodemographics and impairment status. Furthermore, the negative direction of the individual effects indicates that the more participants used either of the coping modes, the less mental health problems they reported. It is also interesting to note that in comparison to the other increments, the largest proportion of the 62% total variance was accounted for by the coping modes.

The relative importance of both coping modes in the prediction of mental health problems was further examined by comparing the degree of overlap in their confidence intervals. Although the standardized regression coefficients for assimilative and accommodative coping seemed to differ in terms of magnitude and/or significance in both regression sets, the comparison of confidence intervals showed that there was some overlap. Therefore, it cannot be concluded that these coefficients were significantly different. However, a trend can be noted in that the coefficients for accommodative coping were consistently higher compared to those for assimilative coping.

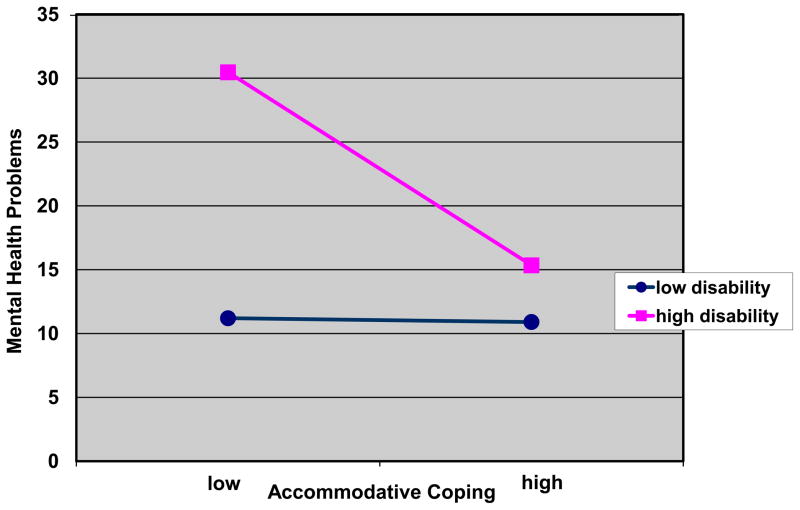

The last block with the four interaction terms added a significant increment of 9% over and above the prior three blocks predicting mental health problems. Contrary to prediction, the two-way interaction between age and accommodative coping was not significant. However, the other two two-way as well as the three-way interaction showed significant effects on mental health problems. Findings suggest that the effect of the accommodative coping mode varied depending on participants level of disability but only under the condition of younger age. The three-way interaction of accommodative coping, functional disability, and age is depicted for younger age in Figure 1.1, and for older age in Figure 1.2. It appears that, under the condition of younger age, the beneficial effect of accommodative coping on mental health problems became increasingly pronounced when levels of functional disability were high. In contrast, under the condition of older age, this effect of accommodative coping did not depend on levels of disability. Rather, the beneficial effect of accommodative coping was there regardless of disability levels. Further, a comparison of the two figures confirms the finding from the two-way interaction of age and disability, that negative mental health effects of high disability seemed to be the most pronounced under the condition of younger age.

Figure 1.1.

Younger Age

Predicted regression lines for three-way interaction of accommodative coping, functional disability, and age predicting mental health problems

Figure 1.2.

Older Age

Predicted regression lines for three-way interaction of accommodative coping, functional disability, and age predicting mental health problems

Discussion

Study findings support the importance of accommodative and assimilative modes of coping for mental health outcome among middle-aged and older adults with a chronic impairment. Specifically, the observation that the link between accommodative coping and depressive symptoms was stronger than previously found suggests that mental health benefits of accommodative coping may be stronger in a chronically impaired group than in the general aging population. Future research comparing a chronically disabled with a non-disabled group of older adults in this regard could clarify if this is indeed the case.

The key finding of the present study, which extended prior evidence based on the general aging population, was that the effect of accommodative coping on mental health problems varied depending on both functional disability and age. However, the beneficial effect of accommodative coping that existed in the older group independently of disability level emerged in the younger group only with high levels of disability, which underscored that disability rather than age became the critical variable among the middle-aged participants. Thus, the hypothesized difference in the impact of accommodative coping on mental health depending on age did exist but only when those with lower levels of disability in the younger group were compared to the older participants. These findings are not inconsistent with the conceptual framework if one considers the notion that the role of accommodative coping becomes increasingly important in old age due to the losses and constraints that typically accompany later life. Thus, if a younger age group is included that deals with the kind of functional loss and resulting limitations that often characterize old age, functional disability rather than age should become the critical variable. Thus, the notable implication of these findings for the theoretical framework of accommodative and assimilative coping seems to be that predictions about an age-related shift from assimilation towards accommodation need to be modified when the situation of a chronically impaired population is addressed. Evidence from the present study suggests that, in this population, the projected shift may occur much earlier than “normative” in younger age groups, and may even emerge more strongly among younger than among older individuals. These insights may serve as guidance for the formulation of more specific hypotheses that take into consideration the unique situation of dealing with a chronic impairment in middle adulthood. Future work in this direction could help identify those who are at risk for mental heath problems, and guide the design of interventions for middle-aged and older adults with chronic vision impairment as well as other age-related health impairments.

Also of particular relevance for intervention planning is the evidence obtained in the present study, which suggests that dealing with a chronic impairment and related health and disability problems in middle adulthood carries particular implications different from those involved when chronic impairment occurs in later life. In fact, facing a chronic impairment seemed to pose more of a risk for mental health problems for middle-aged than for older adults. One explanation may, again, lay in the off-time nature of having to deal with vision and disability problems at a point in life during which most people enjoy better health. In later adulthood, on the other hand, physical constraints tend to be seen as rather normative, in other words what many people would expect to occur as part of the aging process. Alternately, cohort effects may have played a role in the sense that the older participants, due to life experiences that are characteristic for their generation (e.g., living through the Depression), were more prepared to deal with situational constraints or the experience of loss and limitation of any sort than the middle-aged cohort. Another matter of life experience may have been that with an increasingly unfavorable gain–loss ratio in later life (Heckhausen, Dixon, & P. B. Baltes, 1989) the older participants may have had more exposure to loss in general, and therefore may have been able to draw on this prior experience in order to cope with the new challenge of vision loss. To address the latter possibility, future research could directly assess the role of prior loss experience. The viability of the age-normative explanation could be addressed in further studies on coping with disability across the life span by assessing expectations for what is considered normative by middle-aged and older adults, and by accounting for these expectations in the analysis. Being able to ultimately exclude the cohort effect explanation, however, would require longitudinal data that allow a delineation of the transition from mid- to late adulthood among adults in one cohort, and within this cohort, a comparison of those who develop a chronic impairment in mid-life and those for whom this occurs in later life.

Longitudinal data would also be helpful to integrate and further refine the different attempts to apply life-span theories to the field of adaptation to chronic impairment. For example, there is evidence from the present study and prior research that the model of accommodative and assimilative coping and the life-span theory of control provide a useful framework for this topic. However, as suggested above, the question does not seem to be which of the two theories is more appropriate. Rather, it appears that they provide related, yet distinct concepts and measures that can be used to assess adaptation on different levels, that is general coping tendencies one the one hand, and control-related behavior on the other. The usefulness of assessing these separately may be underscored by the fact that Wahl and colleagues found no relationship of compensatory secondary control with emotional adjustment, while the present study demonstrated an important role of the conceptually related accommodative mode for mental health outcome. Yet, it is also possible that these findings differed because the participants in the present study were at a more advanced point of the adaptation process. Thus, future research that would enable us to tease apart the similarities and differences of these concepts, and to determine their exact role in adaptation to chronic impairment would have important theoretical as well as clinical implications for the field of adult development and aging.

As participants were drawn from a population who had contacted a vision rehabilitation agency for services, there may be limits to generalizing the presented findings to visually impaired adults who do not seek out services or to adults with other chronic impairments (e.g., hearing). However, this should not limit the relevance of determining the role of coping tendencies in the relationship between vision loss, functional disability, and mental health in middle- and late-adulthood. Finally, age-related vision loss constitutes a prototypical case in that it shares key features with other chronic age-related disabilities, such as gradual onset, progressive decline, and partial disability. Therefore, the present study can serve to inform and guide future research on adaptation to age-related disability in general.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (1 R03 MH65382). The author would like to thank Amy Horowitz, Mark Brennan, Joann P. Reinhardt, and Jochen Brandtstädter for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript, Chistopher Meehan for his role in the data collection, and study participants for sharing their time and life experiences with us.

Footnotes

It should be noted that while the assimilative mode may be compared to problem-focused coping in that it includes concrete problem-solving efforts, the accommodative mode, unlike emotion focused coping, is specifically conceptualized as a subintentional process of restructuring and reevaluating goal hierarchies. In fact, as Brandtstädter and Renner (1990) pointed out, some of the strategies in the emotion-focused category may even impede accommodative reorientation processes.

Interactive effects involving assimilative coping were not included into the final regression model because they were not expected based on prior research. However, it is noted that a preliminary set of regressions confirmed that there were indeed no such effects.

References

- Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In: Baltes PB, Baltes MM, editors. Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan M, Hamm-Baugn VP. The relationship between chronic illness and depression in a community of urban black elderly persons. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1995;50B (2):S119–S127. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.2.s119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benn D. Dissertation Abstracts International. 04-B. Vol. 58. 1997. The role of personality traits and coping strategies in late-life adaptation to vision loss. (Doctoral dissertation, Fordham University) p. 2151. [Google Scholar]

- Benn D, Reinhardt JP. Coping as a predictor of adaptation in elders with age-related vision impairment. Poster presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Gerontological Society of America; Philadelphia, PA. 1999. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J. Sources of resilience in the aging self. In: Hess TM, Blanchard-Fields F, editors. Social Cognition and Aging. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, Renner G. Tenacious goal pursuit and flexible goal adjustment: Explication and age-related analysis of assimilative and accommodative strategies of coping. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:58–67. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, Rothermund K. Self-percepts of control in middle and alter adulthood: Buffering losses by rescaling goals. Psychology and Aging. 1994;5:58–67. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.9.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, Rothermund K. The life-course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal adjustment: A two-process framework. Developmental Review. 2002;22:117–150. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, Greve W. The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Developmental Review. 1994;14:52–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, Wentura D, Greve W. Adaptive resources of the aging self: Outlines of an emergent perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1993;16:323–349. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan M, Horowitz A, Reinhardt JP, Cimarolli V, Benn D, Leonard R. In their own words: Strategies developed by visually impaired elders to cope with vision loss. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2001;35(1):107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan M, Silverstone B. Developmental perspectives on aging and vision loss. In: Siverstone B, Lang MA, Rosenthal BP, Faye EF, editors. The Lighthouse handbook on vision impairment and vision rehabilitation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 409–429. [Google Scholar]

- Carabellese C, Appollonio I, Rozzini R, Bianchetti A, Frisoni GB, Frattola L, Trabucchi M. Sensory impairment and quality of life in a community elderly population. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1993;41:401–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Situational coping and coping dispositions in a stressful transaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:184–195. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development. Multidimensional functional assessment: The OARS methodology. 1. Durham, NC: Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Earle JR, Smith MH, Harris CT, Longino CF., Jr Women, marital status, and symptoms of depression in a midlife national sample. Women and Aging. 1998;10(1):41–57. doi: 10.1300/j074v10n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst C, Angst J. The Zurich Study. XII. Sex differences in depression. Evidence form longitudinal epidemiological data. European Archives in Psychiatry Clinical Neurosis. 1992;241(4):222–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02190257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye EF. Functional consequences of vision impairment: Visual function related to eye pathology. In: Silverstone B, Lang MA, Rosenthal BP, Faye EF, editors. The Lighthouse handbook on vision impairment and vision rehabilitation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 791–798. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DP, Williams P. A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-NELSON; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J. Developmental regulation Across Adulthood: Primary and Secondary Control of Age-Related Challenges. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:176–187. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J, Dixon RA, Baltes PB. Gains and losses in development throughout adulthood as perceived by different adult age groups. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A, Reinhardt JP. Mental health issues in visual impairment: Research in depression, disability, and rehabilitation. In: Silverstone B, Lang MA, Rosenthal BP, Faye EF, editors. The Lighthouse handbooks on vision impairment and vision rehabilitation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 1089–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A, Reinhardt JP, Boerner K, Travis L. The influence of health, social support, and rehabilitation on depression among disabled elders. Aging & Mental Health. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000150739. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A, Reinhardt JP, McInerney R, Balistreri E. Final Report submitted to the AARP Andrus Foundation. New York: The Lighthouse Inc; 1994. Age-related vision loss: Factors associated with adaptation to chronic impairment over time. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A, Teresi JE, Cassels LA. Development of a Vision Screening Questionnaire for Older People. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1991;17:37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Karlson JS. Self-reports of psychological distress in connection with various degrees of vision impairment. Journal of Vision Impairment & Blindness. 1998;92:483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Kohout FJ, Berman F, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger J, Heckhausen J. Personality development across the adult life span: Subjective conceptions vs. cross-sectional contrasts. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1993;48:100–108. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.3.p100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang FR, Rieckman N, Baltes MM. Adapting to aging, losses: Do resources facilitate strategies of selection, compensation, and optimization in everyday functioning? Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2002;57B(6):501–509. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.p501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson V, Marano MA, editors. National Center for Health Statistics. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 1993 [CD-ROM] Hyattsville, MD: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Publications from the National Center for Health Statistics; 1993. [I No.2, November 1996] [Google Scholar]

- National Society for the Prevention of Blindness. Survey ’84: Attitudes towards blindness prevention. Sight-Saving. 2000;53:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Neugarten B. Adaptation and the life cycle. The Counseling Psychologist. 1976;6(1):16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt JP. The importance of friendship and family support in adaptation to chronic vision impairment. Journal Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1996;51:268–278. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.5.p268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt JP. Effects of positive and negative support received and provided on adaptation to chronic visual impairment. Applied Developmental Science. 2001;5:76–85. [Google Scholar]

- The Lighthouse, Inc. The Lighthouse National Survey on Vision Loss: The experience, attitudes and knowledge of middle-aged and older Americans. New York: The Lighthouse Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl HW, Oswald F, Zimprich D. Everyday competence in visually impaired older adults: A case for person-environment perspectives. The Gerontologist. 1999;39(2):140–149. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl HW, Oswald F. The person-environment perspective of vision impairment. In: Silverstone B, Lang MA, Rosenthal BP, Faye EF, editors. The Lighthouse handbooks on vision impairment and vision rehabilitation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 1069–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl HW, Schilling O, Becker S, Burmedi D. A German research program on the psychosocial adaptation to age-related vision impairment: Recent findings based on a control theory approach. European Psychologist in press. [Google Scholar]