Abstract

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) material presents a readily available resource in the study of various biomarkers. There has been interest in whether the storage period has significant effect on the extracted macromolecules. Thus, in this study, we investigated if the storage period had an effect on the quantity/quality of the extracted nucleic acids and proteins. We systematically examined the quality/quantity of genomic DNA, total RNA, and total protein in the FFPE blocks of malignant tumors of lung, thyroid, and salivary gland that had been stored over several years. We show that there is no significant difference between macromolecules extracted from blocks stored over 11–12 years, 5–7 years, or 1–2 years in comparison to the current year blocks.

Introduction

Formalin fixation and paraffin embedding of tissues preserves the morphology and cellular details of tissue samples. Thus it has become the standard preservation procedure for diagnostic surgical pathology. The long-term storage of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks at ambient temperature is more cost effective than storing frozen tissues at ultra-low temperatures due to maintenance, space, and labor costs. Pathology departments routinely archive vast numbers of FFPE blocks as compared to frozen tissues. This largely untapped resource represents an extensive repository of tissue material with a long-term clinical follow-up,1 providing a valuable resource for translational clinical research.

Since the first publication of use of antigen retrieval to facilitate immunohistochemistry (IHC) on FFPE samples in 1991 by Shi and associates,2 the use of FFPE blocks for IHC has become an accepted procedure in diagnostic pathology. Further, the use of antigen retrieval techniques for extraction of DNA, RNA, and proteins from FFPE tissues allows for a combinatorial approach in terms of preservation of both morphology and molecules in cell/tissue samples.2 Recent technical advances in the field of molecular biotechnology have made it possible to extract nucleic acids and proteins from FFPE blocks to be used in downstream applications.

Proteins isolated from FFPE blocks have been successfully used in Western blot analysis, reverse-phase arrays, and surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight MS,3 while DNA obtained, though highly fragmented, can be used for successful amplification of shorter amplification products up to 250 bp in length.4 Even when the samples were partially degraded, the extracted DNA proved to be suitable for the downstream analysis by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) procedure in combination with sequence-specific oligonucleotide (SSO) probe procedures.5 In FFPE samples, because RNA is assumed to degrade over time into small fragments, the RNA quality indicators such as RNA Integrity Number (RIN; Agilent Bioanalyzer) or RNA Quality Indicator (RQI; Bio-Rad Experion, Hercules, CA) are much lower than in frozen tissues. However, even a RIN of 1.4 (with 1 representing totally degraded RNA to 10 for completely intact RNA) has been successfully used for gene expression analysis.6 The DNA and miRNA extracted from FFPE blocks have currently reached levels that allow their application as a first-line approach in the search for biomarkers.7

Though several studies have been done using extracted RNA, DNA or protein or a combination of nucleotides in the downstream analysis, there is a lack of understanding of the quantitiy and quality of RNA, DNA, and protein that could be extracted from FFPE blocks stored over a period of time and comparison to current (less than a year) blocks. In this study, we examined whether the storage period had any effect on the quantity/quality of the extracted nucleic acids and proteins. This was accomplished by systematically examining the quality and quantity of genomic DNA, total RNA, and total protein in the FFPE blocks of malignant tumors of lung, thyroid, and salivary gland that had been archived for 11–12 years, 5–7 years, 1–2 years, or current blocks stored for less than one year (4–9 months).

Materials and Methods

Human tissue samples

The study was conducted in accordance with the policies stated by the University of Pennsylvania IRB. Tissue samples were provided by the Cooperative Human Tissue Network which is funded by the National Cancer Institute. Other investigators may have received specimens from the same subjects.

Based on the availability of remnant resections of the surgical tissues, FFPE blocks of malignant tumors of lung, thyroid, and salivary gland [archived for 11–12 years, 5–7 years, 1–2 years, or less than one year (4–9 months)] (Table 1), were investigated in this study. The FFPE blocks were stored at temperatures maintained in the range of 17°C–22°C and humidity levels of 20%–60%. The tissue samples used in this study were fixed in Neutral buffered Formalin for 24–48 h prior to machine processing. The post-fixation processing of the tissues was completed in the same histopathological laboratory using consistent processor protocols over years. Briefly, post-fixation, the tissues were fixed in 10% phosphate buffered formalin for 2 h, followed by tissue processing for 10 h, and paraffin embedding for 20 min.

Table 1.

Pathologic Diagnosis of FFPE Blocks

| FFPE tissue type | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Archival time | Lung | Thyroid | Salivary Gland |

| 11–12 years | Squamous cell carcinoma (2) Adenocarcinoma (1) |

Papillary carcinoma (6) | Acinic cell carcinoma (1) Squamous carcinoma (2) |

| 5–7 years | Adenocarcinoma (3) | Papillary carcinoma (3) | Acinic cell carcinoma (1) Squamous carcinoma (2) |

| 1–2 years | Adenocarcinoma (1) Squamous carcinoma (2) |

Papillary carcinoma (3) | Squamous carcinoma (1) Poorly differentiated carcinoma (1) Carcinoma. Mixed tumor (1) |

| <1 year | Squamous carcinoma (1) Adenocarcinoma (4) |

Papillary carcinoma (2) Anaplastic carcinoma (1) |

Acinic cell carcinoma (1) Squamous carcinoma (1) Ductal carcinoma (1) |

Frozen samples corresponding to malignant lung (n=4), thyroid (n=3), and salivary gland (n=3) were chosen as controls (Table 2). The frozen tissues chosen were independent of FFPE blocks and did not have a matching FFPE block counterpart. The timeline on frozen samples ranged from 4 months to 2 years.

Table 2.

Pathologic Diagnosis of Snap-Frozen Control Tissues

| Frozen tissues | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lung | Thyroid | Salivary gland |

| Sarcomatoid carcinoma (1) | Papillary carcinoma (2) | Carcinoma mixed tumor (2) |

| Adenocarcinoma (3) | Medullary carcinoma (1) | Squamous carcinoma (1) |

RNA/DNA extraction from FFPE tissue

Total RNA/DNA was isolated from the same set of three to four 10 μm tissue curls cut from each FFPE blocks. Prior to sectioning, the microtome and accessories were cleaned with RNAse AWAY. The tissue curls were collected in individually sealed sterile 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and were baked at 56°C for 15 min to soften the paraffin wax, followed by deparaffinization in xylene and 100% ethanol. Following the dewaxing, the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE (Qiagen Corp, CA) kit protocol was followed. Total RNA was extracted in 60 μL of RNAase-free water, while DNA was extracted in 70 μL of ATE buffer. The concentrations of RNA and DNA were determined using the Tecan 16-plate nanoquant plate and the quality was determined by 260/280 OD ratio and automated gel electrophoresis using Experion (Bio-Rad Inc., Hercules, CA). In addition for RNA, RQI was calculated from the electropherogram. A minimum RQI of 1.4 was considered as threshold for RNA of useful quality. Total liver RNA (Bio-Rad Inc.) was used as a positive gel control.6

Protein extraction from FFPE tissue

Protein was extracted using three to four 10 μm tissue curls from each FFPE blocks. Deparaffinization was accomplished as stated above. Following the dewaxing, the protocol of Qproteome FFPE Tissue kit (Qiagen Corp.) was followed. Protein was extracted in 100 μL of Extraction Buffer and the concentration was determined using BCA assay and the quality was determined by running 6 μL of the samples on automated gel electrophoresis using Experion (Bio-Rad Inc.). The housekeeping protein GAPDH (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used as gel control.

RNA/DNA/protein extraction from frozen samples

RNA, DNA, and proteins were simultaneously extracted from the same frozen tissue. Briefly, 30 mg of frozen samples stored at −80°C were further cooled in liquid nitrogen and freeze-fractured in Covaris TT1® tissue tubes using the Covaris CryoPrep™ pulverization system at an impact setting of 5. The pulverized tissues were then transferred to Tissuelyser LT (Qiagen Corp.) and homogenized for 5 min. All Prep RNA/DNA and Protein kit (Qiagen Corp.) protocol was followed. The concentrations and quality for RNA, DNA, and protein were examined as described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses for variance were performed using Kruskall-Wallis test (PROSTAT software, Pearl River, NY) to estimate whether the samples and the population from which they came have the same curve form.8

Results

Nucleic acid quality

DNA and RNA were analyzed using the Nanoquant method. The 260/280 nm values for all the tissues indicated that both DNA and RNA purity obtained from FFPE tissues were comparable to those obtained from frozen tissues as seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Nucleic Acid Quality in Terms of 260/280 Ratios for Malignant Lung, Thyroid and Salivary Gland. A) DNA and B) RNA from FFPE Blocks (N=41) and Frozen Tissues (N=10). Data Represented as Mean±SD.

| A) | Lung DNA | Thyroid DNA | Salivary gland DNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFPE11–12 years | 1.90±0.08 | 1.90±0.02 | 2.03±0.10 |

| FFPE5–7 years | 2.23±0.46 | 1.96±0.34 | 1.86±0.27 |

| FFPE1–2 years | 2.01±0.09 | 1.91±0.07 | 2.02±0.04 |

| FFPE<1 year | 2.09±0.27 | 2.05±0.06 | 2.02±0.05 |

| Frozen | 2.01±0.09 | 1.91±0.01 | 1.91±0.04 |

| B) | Lung RNA | Thyroid RNA | Salivary gland RNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFPE11–12 years | 1.95±0.04 | 1.96±0.02 | 1.97±0.04 |

| FFPE5–7 years | 2.09±0.18 | 2.18±0.24 | 2.17±0.19 |

| FFPE1–2 years | 2.06±0.02 | 2.06±0.02 | 1.98±0.04 |

| FFPE<1 year | 2.03±0.09 | 1.97±0.14 | 2.00±0.13 |

| Frozens | 2.11±0.14 | 2.16±0.12 | 2.12±0.02 |

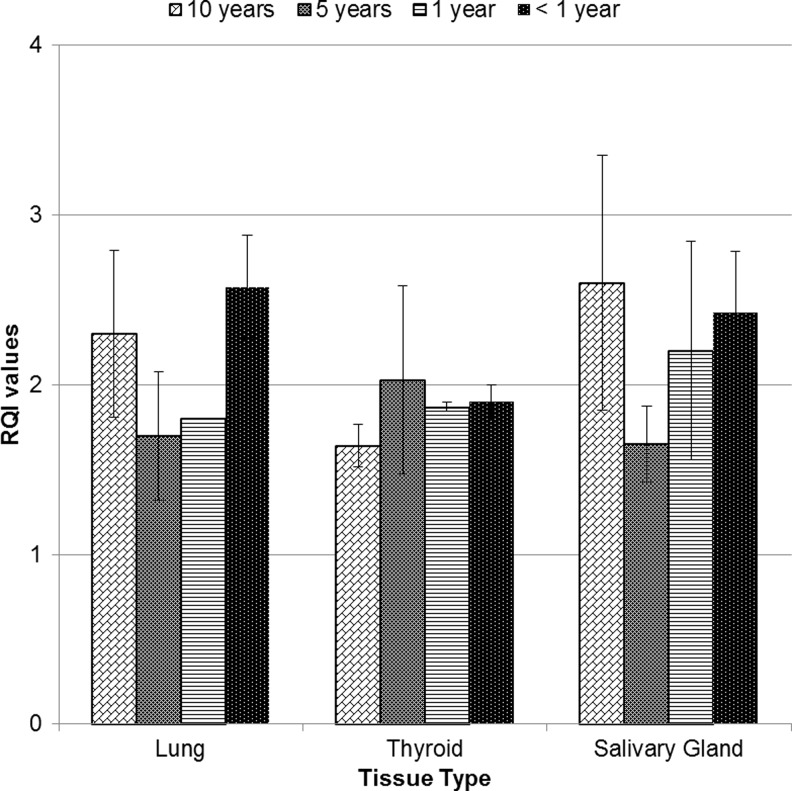

RNA integrity quality using RQI

A comparison was made between the RQI values obtained for the total RNA extracted from FFPE tissues and frozen tissues. The frozen tissues demonstrated higher RQI values (Table 4) in comparison to FFPE tissues. In the analysis of FPPE blocks, minimal variance was seen in the quality of RNA extracted from archived FFPE tissues from 11–12 years, 5–7 years, 1–2 years, and less than 1 year (4– 9 months). In addition, minimal/no significant differences were observed in RQI values among different type of tissues (lung, thyroid, and salivary gland) (Fig. 1).

Table 4.

RQI Values of A) Malignant Lung RNA, B) Malignant Thyroid RNA, and C) Malignant Salivary Gland RNA

| A) | Lung FFPE 11–12 years | Lung FFPE 5–7 years | Lung FFPE 1–2 years | Lung FFPE <1 year | Lung Frozen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±S.E.M | 2.1±0.74 | 1.7±0.38 | 1.8 | 2.63±0.44 | 6.7±0.74 |

| Range | 1–3.5 | 1–2.3 | N/A | 1.8–3.3 | 5.7–8.9 |

| # of blocks analyzed | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| # of blocks RQI>1.4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| B) | Thyroid FFPE 11–12 years | Thyroid FFPE 5–7 years | Thyroid FFPE 1–2 years | Thyroid FFPE <1 year | Thyroid Frozen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±S.E.M | 1.6±0.16 | 2.03±0.55 | 1.87±0.03 | 1.9±0.1 | 7.27±0.42 |

| Range | 1.8–2.3 | 1.0–2.9 | 1.8–1.9 | 1.8–2.1 | 6.8–8.1 |

| # of blocks analyzed | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| # of blocks RQI>1.4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| C) | Salivary gland FFPE 11–12 years | Salivary gland FFPE 5–7 years | Salivary gland FFPE 1–2 years | Salivary gland FFPE <1 year | Salivary gland Frozen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±S.E.M | 1.87±0.03 | 1.87±0.07 | 2.03±0.64 | 2.6±0.44 | 7.23±0.77 |

| Range | 1.8–1.9 | 1.8–2.0 | 1.0–3.2 | 1.9–3.4 | 6.1–8.7 |

| # of blocks analyzed | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| # of blocks RQI>1.4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

FIG. 1.

RQI values for FFPE and frozen tissues. Comparison of RQI values obtained over several time points for malignant lung thyroid and salivary gland FFPE blocks (n=41) and frozen tissues (n=10). Data represented as Mean±S.E.M.

Analyses of lung FFPE tissues showed that 67% were above the minimum threshold for RQI in 12 year and 5–7 year groups, whereas all cases in 1–2 year and less than 1 year were higher than the minimum threshold RQI value. In thyroid FFPE tissues stored for 12 years, 1–2 years, and less than 1 year, the RQI>1.4 and were considered usable. The 5–7 year group had only one block that had a RQI value less than 1.4, making 67% of the 5-year group usable. Similarly, one block of salivary gland FFPE tissue stored for 1–2 years had a RQI value less than 1.4, while the rest of the blocks stored over 12 years, 5–7 years, and less than a year had RQI values>1.4. Statistical analyses indicated that the differences observed were not significant.

Nucleic acid quantity

Concentrations of both RNA and DNA were determined using the absorbance at 260 nm. The values obtained for both FFPE and frozen blocks are represented in Figures 2 and 3 for RNA and DNA, respectively.

FIG. 2.

RNA concentrations for FFPE and frozen tissues. Comparison of RNA concentration values obtained over several time points for malignant lung thyroid and salivary gland FFPE blocks (n=41) and frozen tissues (n=10). Data represented as Mean±S.E.M.

FIG. 3.

DNA concentrations for FFPE and frozen tissues. Comparison of DNA concentration values obtained over several time points for malignant lung thyroid and salivary gland FFPE blocks (n=41) and frozen tissues (n=10). Data represented as Mean±S.E.M.

Protein concentration and profile

The concentration of extracted protein was calculated by BCA assay using bovine serum albumin as standard. The concentrations obtained for both FFPE and frozen tissues are represented in Figure 4.

FIG. 4.

Protein concentrations for FFPE and frozen tissues. Comparison of protein concentration values obtained over several time points for malignant lung thyroid and salivary gland FFPE blocks (n=41) and frozen tissues (n=10). Data represented as Mean±S.E.M.

Protein extraction from FFPE and frozen tissues were run on microchip for electrophoresis profiles. A commonly used housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as control for electrophoresis. A representative of protein electropherogram showing protein fragmentation pattern across various years in represented in Figure 5. The positive control, GAPDH (37 kDa), a housekeeping protein, can be seen across various years. The figure shows that the protein extractions from 5 years and above have more fragmentation than from 1 year or less than one-year stored samples.

FIG. 5.

Protein electropherogram. Representive run of protein samples obtained from FFPE blocks. Molecular marker (Lane 1), positive control GAPDH (37 kDa) (Lane 2), 10-year malignant lung (Lanes 3, 4), 5-year malignant lung (Lanes 5, 6), 1-year malignant lung (Lanes 7, 8), less than a year (Lanes 9, 10), and frozen tissues (Lanes 11, 12).

Statistical analyses using Kruskal-Wallis test for the analysis of distribution for each molecular derivative across various years for each tissue showed that the null hypothesis cannot be rejected. This implied that there is no significant difference in values obtained across various years.

Discussion

Historically, the archived FFPE blocks have been successfully used for immunohistochemistry application. However, formalin-fixed archival samples are known to be poor materials for molecular biological applications due to the irreversible modifications caused by formalin fixation on macromolecules.9 In the last 10 years, there has been an exponential increase in the development of molecular assays by employing FFPE blocks. At present, when sections from FFPE blocks are to be used for molecular extraction, attention is paid to the time of fixation in formalin so as not to cause overfixation. The current era of personalized medicine requires analyzing a larger cohort of samples to study various biomarkers used for targeted therapies and prognosis. Therefore, access to archived samples of FFPE material presents a readily available resource to meet this need.

The advances in the field of molecular biological techniques have attempted to overcome the issue of formalin cross-linking and have successfully extracted DNA, RNA, and proteins, albeit fragmented. These fragmented macromolecules have been resourcefully used in downstream analyses where short fragments can be utilized. For instance, fragmented DNA has been used in PCR for amplification, while micro RNAs, due to their small size of the 21–22 nucleotides, are currently studied for biomarker analysis. Similarly peptides obtained from protein extraction have been used in mass spectrometry analyses for understanding the molecular mechanism of diseases. Therefore, there has been an interest in whether the storage period has significant effects on the extracted macromolecules. In FFPE blocks, residual formalin within some FFPE tissues continues to react with DNA during sample storage. Thus analysis of DNA is a crucial first step in acquiring meaningful data from FFPE tissues.10

Our results show that in terms of quantity and quality, for all FFPE tissues DNA extracted from FFPE blocks from 11–12 years, 5–7 years, and 1–2 year are comparable to DNA extracted from FFPE blocks stored for less than a year. Similar results were obtained for total protein extracted from all the three tissue types studied. Overall RNA concentration was less when compared to DNA concentrations; while most of the extracted RNA was considered adequate/usable (RQI>1.4). In particular, analysis of average RQI for FFPE blocks did not show a significant difference between the blocks that were processed within several months before analyses and those that had been stored for 11–12 years, 5–7 years, or 1–2 years.

In this study, we used frozen tissues as controls. The frozen tissues used were not matched in their storage periods to the FFPE tissues. This was done to reflect the scenario in clinical settings where there is generally a large repository of FFPE tissues but frozen material is collected prospectively. We extracted RNA and DNA from the same set of FFPE tissue curls while protein was extracted from the subsequent tissue curls. A wide range in concentration of the molecular derivatives was seen across the cases. This can be mainly be attributed to the fact that 71% of the samples had tumor cellularities ranging from 40%–100%. Even though greater protein fragmentation pattern was seen in FFPE tissues stored for more than 5 years, the positive control (GAPDH) was seen in all cases, suggesting the usability of older FFPE cases in fit-for-purpose studies. This result may be attributed to the modifications of protein by formalin. It was observed, in the analysis of formalin-fixed synthetic homo-oligo RNAs, that the reaction between formaldehyde and nucleotide monomers results in the addition of a formaldehyde group to a base in the form of N-methylol (N-CH(2)OH), followed by an electrophilic attack on N-methylol on an amino base to form a methylene bridge between two amino groups.9

To our knowledge, this is the second study to report the extraction of nucleic acid from the same set of FFPE curls, and the first to have protein extracted from the same tissue for comparison. We believe that the results of our study are significant in light of the variability in processing of tissue to a FFPE block since fixation in formalin is largely dependent on specimen size and time of processing.11 Our results show that, despite the variability in tissue collection and processing, FFPE tissue blocks stored up to 12 years can be used to extract adequate and usable RNA, DNA, and protein.

Several studies have investigated the effect of the storage period on either RNA or DNA and the use of extracted material in downstream analysis.4–6 Extraction of RNA and DNA from different sections of tissues may not always be possible when the tissue size is limited. Thus, extracting RNA and DNA from same sections is valuable and it has been recently shown that an effective extraction for RNA and DNA can be done using the same sections.12 However, none have shown all three types of macromolecules (i.e., RNA, DNA and proteins) extracted from the same FFPE block. We show that RNA, DNA, and protein can be successfully extracted from one archived FFPE block stored over several years. This we believe will prove to be of immense value in cases where limited lesional tissue is available for biomarker analysis to predict prognosis and devise personalized therapies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Ms. Gina Piermatteo, Ms. Munia Islam, and Mr. Andrew Tieniber for helping with the histopathological processes.

Disclosure Statement

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (Grant No. CA-044974). There are no potential conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Gnanapragasam VJ. Unlocking the molecular archive: The emerging use of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue for biomarker research in urological cancer. BJU Int. 2010;105:274–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi SR. Shi Y. Taylor CR. Antigen retrieval immunohistochemistry: Review and future prospects in research and diagnosis over two decades. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:13–32. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2010.957191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scicchitano MS. Dalmas DA. Boyce RW. Thomas HC. Frazier KS. Protein extraction of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue enables robust proteomic profiles by mass spectrometry. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:849–860. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.953497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dedhia P. Tarale S. Dhongde G. Khadapkar R. Das B. Evaluation of DNA extraction methods and real time PCR optimization on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Impraim Chaka C. Saiki Randall K. Erlich Henry A. Teplitz RL. Analysis of DNA extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues by enzymatic amplification and hybridization with sequence-specific oligonucleotides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;142:710–716. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91472-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribeiro-Silva A. Zhang H. Jeffrey SS. RNA extraction from ten year old formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded breast cancer samples: A comparison of column purification and magnetic bead-based technologies. BMC Mol Biol. 2007;8:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klopfleisch R. Weiss AT. Gruber AD. Excavation of a buried treasure—DNA, mRNA, miRNA and protein analysis in formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissues. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26:797–810. doi: 10.14670/HH-26.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan Y. Walmsley RP. Learning and understanding the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis-of-variance-by-ranks test for differences among three or more independent groups. Phys Therapy. 1997;77:1755–1762. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.12.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuda N. Ohnishi T. Kawamoto S. Monden M. Okubo K. Analysis of chemical modification of RNA from formalin-fixed samples and optimization of molecular biology applications for such samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4436–4443. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michalik S. Overcoming poor quality DNA. Drug Disc Devel. 2008;11:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung JY. Braunschweig T. Williams R, et al. Factors in tissue handling and processing that impact RNA obtained from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:1033–1042. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.951863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotorashvili A. Ramnauth A. Liu C, et al. Effective DNA/RNA co-extraction for analysis of microRNAs, mRNAs, and genomic DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]