Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to evaluate preoperative treatment with full-dose gemcitabine, oxaliplatin and radiation (RT) in localized pancreatic cancer.

Methods

Eligibility included confirmation of adenocarcinoma, resectable or borderline resectable disease, PS≤2, and adequate organ function. Treatment consisted of two, 28 day cycles of gemcitabine (1g/m2 over 30 minutes days 1, 8, 15) and oxaliplatin (85mg/m2 days 1, 15) with RT during cycle 1 (30Gy in 2Gy fractions). Patients were evaluated for surgery following cycle 2. Resected patients received 2 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Results

Sixty-eight evaluable patients were treated at 4 centers. By central radiology review, 23 patients were resectable, 39 borderline resectable, and 6 unresectable. Sixty-six patients (97%) completed cycle 1/RT and 61 patients (90%) cycle 2. Adverse events ≥ grade 3 during preoperative therapy included neutropenia (32%), thrombocytopenia (25%), and biliary obstruction/cholangitis (14%). Forty-three patients were resected (63%) with R0 resection in 36 (84%). Median overall survival for all patients was 18.2 months (95%CI 13–26.9), those resected 27.1 months (95%CI 21.2–47.1) and those not resected 10.9 months (95%CI 6.1–12.6). A decrease in CA19-9 following neoadjuvant therapy was associated with R0 resection (p=0.02) which resulted in a median survival of 34.6 months (95% CI 20.3–47.1). Fourteen patients (21%) are alive and disease-free at a median follow-up time of 31.4 months (range, 24–47.6).

Conclusion

Preoperative therapy with full dose gemcitabine, oxaliplatin and RT was feasible and resulted in a high percentage of R0 resections. Results are particularly encouraging given a majority of patients with borderline resectable disease.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, neoadjuvant, gemcitabine, oxaliplatin

Introduction

Pancreatic carcinoma is associated with a poor prognosis in all stages1. In patients presenting with resectable disease, surgery offers a potential for cure and post-operative therapy provides benefit1–4. Unfortunately, a majority of patients with localized pancreatic cancer present with borderline resectable or unresectable disease and initial surgical therapy is unlikely to result in a complete resection1,5,6.

In contrast to surgery first, preoperative therapy offers advantages for patients with localized pancreatic cancer. Patients receive systemic therapy sooner, generally with better tolerance and compliance. Preoperative treatment appears to increase the rate of margin-negative resections in borderline lesions7,8. Furthermore, recognition of metastatic disease during preoperative therapy spares patients a major surgery. Finally, isolated local progression during preoperative therapy precluding resection appears uncommon, as reported in two sequential studies involving 176 patients9,10.

We previously conducted a phase I study of oxaliplatin added to full dose gemcitabine and radiation in pancreas cancer11. This approach is intended to maximize systemic therapy while simultaneously enhancing effects of radiation12–15. Based on safety and encouraging results in patients with resectable disease, we report here, a multi-institution phase II study of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer.

Patients and Methods

Patients with pathologic confirmation of pancreatic carcinoma and localized disease were eligible for this study. Resectability was assessed by multidetector (CT) scan using a multiphase contrast-enhanced technique and applying the National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network (NCCN) criteria (Version 1, 2008). Briefly, tumors were designated as resectable with a clear fat plane around celiac (CA) and superior mesenteric (SMA) arteries and patent superior mesenteric (SMV) and portal veins (PV). Patients were deemed borderline resectable with severe unilateral SMV or PV impingement, tumor abutment of the SMA, gastroduodenal artery encasement up to the origin from the hepatic artery or colon invasion. Further eligibility criteria included life expectancy >12 weeks, Zubrod performance status ≤ 2, and adequate hematologic, renal, and hepatic function. Patients with neuropathy ≥ grade 2, prior therapy for pancreatic cancer, or prior abdominal radiation were not eligible. The institutional review board of each participating institution approved the trial. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to treatment initiation.

Treatment

Protocol treatment consisted of four 28-day cycles of chemotherapy, two cycles before surgery and two cycles following. Gemcitabine (1g/m2 infused over 30 minutes) was administered on days 1, 8, and 15 of each cycle; oxaliplatin (85mg/m2 infused over 90 minutes) was administered on days 1 and 15. Radiation therapy was delivered concurrently with the first cycle of chemotherapy in 2Gy fractions (total dose 30Gy). Three dimensional planning was used limiting target volumes to gross disease with a 1 cm margin and no elective nodal irradiation, as described previously11. Treatment plans were reviewed and approved by a central radiation oncologist (EBJ) prior to initiation.

Patients were evaluated after the second cycle of chemotherapy and with no evidence of metastasis or local progression precluding resection, surgery was offered 2 to 4 weeks from last chemotherapy. Following resection, adjuvant chemotherapy was given, resuming within 12 weeks of surgery.

Adjustments to chemotherapy doses were based on toxicity experienced during prior therapy and platelet and absolute neutrophil count (ANC) on day of treatment. For an ANC ≥ 1,000/mm3 and platelets ≥ 75,000/mm3, full doses were given. For an ANC >500/mm3 and <1000/mm3 and/or platelets >50,000/mm3 and <75,000/mm3, a 50% reduction in gemcitabine and 25% reduction in oxaliplatin was made. For an ANC ≤500/mm3 or platelets ≤50,000/mm3, chemotherapy was held until ANC ≥ 1,000/mm3 and platelets ≥ 75,000/mm3. Both agents were held for any non-hematologic toxicities ≥ Grade 3 with treatment resumption upon improvement to ≤ Grade 2. If chemotherapy was held, when resumed, doses of both agents were reduced 25%. If a hold occurred during cycle 1, radiation treatment was also held. Beyond cycle 1, if chemotherapy was held, then that treatment day was dropped. If toxicity and recovery was not sufficient to allow treatment resumption within 3 weeks, patients were taken off protocol.

Assessment of response and surgical therapy

Interpretation of baseline CT and imaging following preoperative therapy and decision making regarding surgery were made at the institutional level. A blinded post-hoc central review of baseline and pre-surgical CTs was performed upon completion of the study by a single radiologist (IRF). For this report, this central review determined resectability status and response following neoadjuvant therapy per RECIST criteria16.

For all patients undergoing surgery, details collected included the type and duration of surgery, vascular resection and/or reconstruction, estimated blood loss, length of hospitalization, and readmission or re-operation within 30 days. A blinded central pathology review of all resection specimens was performed by a single pathologist (JKG) and included assessment of tumor size, grade, margin status, lymph node number and involvement, and histological evaluation of response to treatment17. Quality of life (QOL) measurements were assessed prior to, during and following therapy and will be subject of a separate report.

Statistical analysis

This trial was designed to show an improvement in 2 year disease-free survival (DFS). The treatment regimen was hypothesized to increase DFS by at least 15 percentage points, based on an estimate of 35% derived from resected patients treated with post-operative adjuvant gemcitabine on the CONKO001 trial3. Sixty-eight patients were required to provide 80% statistical power using a 1-sided test. Secondary endpoints included the rate of successful resection and survival. It was assumed when designing the trial that approximately 70% of those enrolled would be resectable at entry with most undergoing successful resection (R0). However, the proportion of accrued cases that were borderline resectable was significantly higher (~70%) than anticipated (~30%). The trial continued with additional emphasis placed upon determining the rate of R0 resection and clinical outcome in the study population.

The ability to have an R0 resection and tumor response (CR + PR) were tested for significant association with patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics using the chi-square and t test statistics for categorical and continuous data, respectively. The characteristics considered were patient’s age at study entry, race, gender, performance status, baseline overall QOL, baseline assessment of resectability, presence of vessel contact (none, artery and/or vein), tumor site in the pancreas (head, body, tail), tumor size before and after neoadjuvant treatment and RECIST response, CA19-9 pre-treatment value and change following therapy, and histologic response to neoadjuvant treatment. Clinical outcome was defined by overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). The times to events were calculated from the first day of treatment until death (OS), or date of progression or death (DFS). Patients not experiencing the events of interest were censored on their last contact date. Time-to-event endpoints were summarized using the product-limit method of Kaplan and Meier. A best multivariable model to explain overall survival was constructed using the proportional hazards model, modeling simultaneously the covariates found to be significantly associated with survival in univariate analysis. The best model was chosen by iteratively removing non-significant covariates until only significant (p<0.05) covariates remained. P-values at or less that 0.05 were considered significant for all test statistics.

Results

Patient and Primary Tumor Characteristics

Seventy-five patients were consented and registered to the study between July 2007 and February 2010. One patient was ineligible due to a diagnosis of neuroendocrine cancer and 3 patients not receiving any study treatment are not considered further. Seventy-one eligible patients are evaluable for safety. Of these, one patient was removed from study during cycle 1 for non-compliance and 2 additional patients withdrew for reasons not related to toxicity or progression. The final evaluable population consists of 68 patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

| # | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 68 | |

| Treatment Center | ||

| University of Michigan | 29 | 43 |

| Johns Hopkins University | 16 | 23 |

| Ohio State University | 13 | 19 |

| Princess Margaret Hospital | 10 | 15 |

| Median Age | 64 (42–83) | |

| Men/Women | 32/36 | 47/53 |

| PS 0/1/2 | 40/26/2 | 59/38/3 |

| Median Size (cm) | 3.1 (1.4–7.8) | |

| Site of Lesion | ||

| Head | 45 | 66 |

| Body | 18 | 27 |

| Tail | 5 | 7 |

| T Stage (Central Radiology Review) | ||

| T1/T2 | 8 | 12 |

| T3 | 56 | 82 |

| T4 | 4 | 6 |

| Resectability (Central Radiology Review) | ||

| Resectable | 23 | 34 |

| No vessel contact | 13 | |

| PV/SMV contact | 10 | |

| Borderline Resectable | 39 | 57 |

| PV/SMV impingement (no arterial) | 22 | |

| SMA abutment | 14* | |

| Other (contiguous organ involvement) | 3 | |

| Unresectable | 6 | 9 |

| PV/SMV encasement/occlusion | 2 | |

| SMA encasement | 3 | |

| CA contact | 1 | |

| Baseline Ca19-9 – median U/mL (range) | 175 (nd-10776) | |

11 cases with SMA abutment also had venous contact

PV – portal vein, SMV – superior mesenteric vein, SMA – superior mesenteric artery, CA – celiac artery

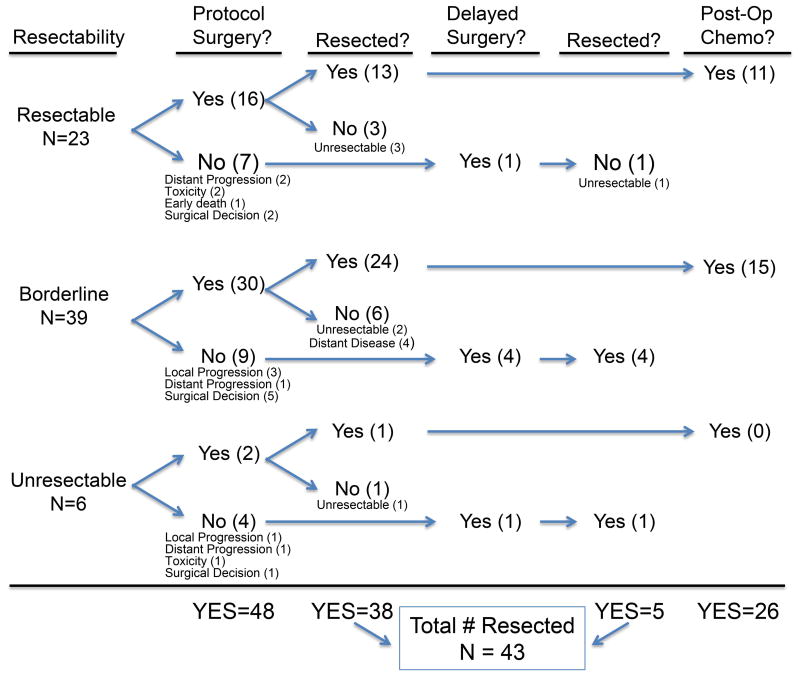

Treatment

Sixty-six (97%) patients completed cycle 1 chemotherapy and radiation (30Gy), with 19 (29%) requiring a delay (generally one week). Sixty-one patients (90%) initiated a second cycle of chemotherapy. Following cycle 2, 4 patients were judged inoperable due to medical condition and 8 patients progressed (12%) either locally (4) or distantly (4) precluding resection (Fig 1). Eight additional patients were removed from protocol to continue chemotherapy as opposed to proceeding to surgery. Six of these patients were subsequently surgically explored as described below.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of evaluable patients grouped by resection status and detailing treatment received. Surgical decision indicates delayed operation for additional off protocol chemotherapy to increase likelihood of resection (see text).

Forty-eight patients (71%) underwent laparotomy per protocol (with 6 additional patients having delayed surgery). In total, 43 patients were resected, (including 5 off protocol), leading to a resection rate of 63% of treated, evaluable patients and 80% of explored patients. Following resection, 26 patients (68%) initiated adjuvant therapy, and 24 (63%) completed a fourth cycle of chemotherapy.

Response

Comparing pre- and post-treatment imaging (Table 2), 5 patients (7%) had partial response and 50 patients (74%) demonstrated stable disease, including 19 (28%) with minor response (10–29% decrease in tumor longest diameter (LD)). Twelve patients had RECIST progression (18%) with increase in tumor LD (9) or metastatic disease (3). Notably, 5 of the 9 patients with RECIST progression had R0 resection without additional therapy. CA19-9 levels available pre- and post-treatment and considered informative (>40 u/ML at least once, n=50) decreased in 74% of patients.

Table 2.

Response to Preoperative Therapy

| # | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Radiographic (n=67) | ||

| PR | 5 | 7 |

| SD | 50 | 74 |

| PD | 12 | 18 |

|

| ||

| Ca19-9 - Elevated pre or post (≥40) | 50 | |

| Decreased | 37 | 74 |

| Increased | 13 | 26 |

|

| ||

| Surgical Pathology | ||

| Centrally reviewed cases | 43 | 100 |

| Size- median (range) | 3 (0.3–5.3) | |

| T stage | ||

| T1/T2 | 11 | 26 |

| T3 | 31 | 72 |

| T4 | 1 | 2 |

| Tumor grade | ||

| 1 | 3 | 7 |

| 2 | 32 | 74 |

| 3 | 8 | 19 |

| Lymph node positive (N1) | 21 | 49 |

| Lymph nodes resected - median (range) | 14 (1–28) | |

| Resection | ||

| R0 | 36 | 84 |

| R1 | 5 | 12 |

| R2 | 2 | 5 |

| Response grade – tumor cell destruction | ||

| 0–50% | 19 | 44 |

| 51–90% | 15 | 35 |

| >90% | 9 | 21 |

Surgical Parameters

Thirty-two patients had a standard pancreaticoduodenectomy and 11 patients had a distal-subtotal pancreatectomy. Vascular resection and/or reconstruction occurred in 17 (40%) cases. The mean operative time was 7.5 hours (range, 2–14 hours), with a mean estimated blood loss of 1010 ml (range, 100–4000 mL). The median duration of hospitalization was 8 days (range, 3–20 days) with 6 patients (14%) re-admitted within 30 days. There was no 30 day peri-operative mortality.

The surgical margins were free of microscopic disease in 36 (84%) cases, 5 were determined to be R1 and 2 were R2 resections. In 19 patients with baseline SMA/celiac arterial contact, 13 patients underwent an R0, and one patient an R1, resection. Regional lymph nodes were involved in 21 of 43 specimens (49%). Treatment effect of at least 50% necrosis was noted in 24 (56%) cases and >90% tumor destruction in 9 cases (21%).

Safety

Grade 3–4 toxicities experienced during preoperative therapy in 71 treated patients are summarized in Table 3. Non-hematologic toxicities occurring in greater than 10% of patients were limited to transaminitis in 13 patients (18%) and biliary obstruction in 10 patients (14%), with associated cholangitis in 8 patients (11%). There were 2 deaths in the pre-operative period; one sudden death following cycle 1, believed cardiopulmonary (autopsy was declined) and a second patient experiencing progressive peritoneal cancer and infection following cycle 1. In total, 18 patients (25%) were hospitalized at least once during the pre-operative period, with 4 patients hospitalized more than once. Lower rates of grade 3–4 toxicities were observed with adjuvant therapy.

Table 3.

Safety

| Neoadjuvant Therapy (n=71) | Adjuvant Therapy (n=38) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 3

|

Grade 4

|

Grade 3

|

Grade 4

|

|||||

| No. of pts | (%) | No. of pts | (%) | No. of pts | (%) | No. of pts | (%) | |

| Hematologic | ||||||||

| Any | 26 | (37) | 13 | (18) | 11 | (29) | 8 | (21) |

| Leukopenia | 22 | (31) | 2 | (3) | 9 | (24) | 3 | (8) |

| Lymphopenia | 12 | (17) | 4 | (6) | 3 | (8) | ||

| Neutropenia | 17 | (24) | 6 | (8) | 7 | (18) | 7 | (18) |

| Anemia | 6 | (8) | ||||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 14 | (20) | 4 | (6) | 5 | (13) | 1 | (3) |

| Non-Hematologic | ||||||||

| Any | 33 | (46) | 1 | (1) | 4 | (11) | ||

| Biliary obstruction | ||||||||

| cholangitis | 8 | (11) | ||||||

| no cholangitis | 2 | (3) | ||||||

| Transaminitis | 13 | (18) | 1 | (3) | ||||

| Dehydration | 5 | (7) | ||||||

| Fatigue | 4 | (6) | ||||||

| Nausea and vomiting | 4 | (6) | ||||||

| Hyperglycemia | 5 | (7) | ||||||

| Hypokalemia | 4 | (6) | ||||||

| Pain | 3 | (4) | ||||||

| Chest pain | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Hypotension | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Anorexia | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Ascites | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Enteritis | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Increased CPK | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Perforated bowel | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Rash | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Syncope | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Thrombosis | 1 | (1) | ||||||

| Neuropathy | 1 | (3) | ||||||

| Weight loss | 1 | (3) | ||||||

| Thrombotic Microangiopathy | 1 | (3) | ||||||

Patient Outcomes

At last follow-up, 48 of 68 patients (71%) have died including 23 of 25 patients (92%) not resected and 25 of 43 patients (58%) surgically treated. The median overall survival was 18.2 months (95% CI 13–26.9) (Fig 2a). For those patients entered with resectable disease, median survival was 26.5 months (95% CI 11.8–44.7) compared to 18.4 months (95% CI 11–27.1) with borderline resectable disease and 9.4 months (95% CI 1.3-NE) with unresectable disease (Fig 2b). Patients undergoing any resection had a median survival of 27.1 months (95% CI 21.2–47.1) versus 10.9 months (95% CI 6.1–12.6) for those not resected (Fig 2c). Median survival for those with R0 resection (n=36) was 34.6 months (95% CI 20.3–47.1). Finally, patients entered with a resectable status and resected (n=13) had a 44.7 months median survival (95% CI 25.6-NE) and those with borderline status and resected (n=28) experienced a 25.4 months median survival (95% CI 16.9-NE) (Fig 2d).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Estimated overall survival of (A) all patients, (B) patients with baseline resectable, borderline resectable, unresectable disease (P = 0.2333), (C) patients either resected or not resected (P < .0001), and (D) patients with either resectable or borderline resectable disease that were either resected or not resected (P < .0001).

Of 41 patients undergoing R0/R1 resection, 22 patients developed recurrent disease at a median time from surgery of 10.4 months (range, 2.3–35.8 months). Recurrent disease was local only in 7 (17%), distant only in 10 (24%), and both in 5 (12%). Five additional patients died without documentation of pattern of recurrence with a median time from surgery to death of 6.9 months (range, 1.8–10.1 months). The 2-year disease-free survival estimate is 26.1% (95% CI: 16.1 – 37.4). Fourteen patients (21%) are alive and disease-free at a median follow-up time of 31.4 months (range, 24–47.6 months).

Patient, tumor and response characteristics were evaluated for significant univariate associations with the occurrence of R0 resection, survival time, and time to disease progression. None of the characteristics (listed in statistics methods section) were significantly associated with R0 resection with the exception of CA19-9 response. Comparing any increase (n=15), to 0–50% decrease (n=13), and > 50% decrease (n=27), demonstrated that a decrease in CA19-9 was associated with R0 resection (p=0.02). Resection (R0 vs. R1/R2 vs. none), baseline QOL, female gender, tumor in body or tail (compared to head) and lower CA 19-9 at baseline (continuous) were associated with improved survival (all p< 0.05). In those undergoing surgical resection (n=43), longer surgery time (p=0.03) and increased blood loss during surgery (p=0.02) were associated with poorer survival, with marginal associations observed with surgical procedure (Whipple inferior to distal-subtotal pancreatectomy p=0.057) and histologic treatment effect (p=0.068). None of the characteristics were associated with time-to-progression.

The best multivariable model to explain overall survival in 68 evaluable patients from the covariates available is presented in Table 4. Incomplete resection (R1/R2) or the inability to be resected was significantly associated with reduced survival along with male gender and tumors located in the head of the pancreas.

Table 4.

Best multivariable model explaining overall survival.

| Characteristic | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resection | |||

| No resection | 5.4 | 2.8 – 10.6 | <0.001 |

| R0 | Reference | ||

| R1/R2 | 1.2 | 0.4 – 3.2 | 0.684 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | Reference | ||

| Male | 2.3 | 1.2 – 4.2 | 0.009 |

| Tumor site on Pancreas | |||

| Head | 2.2 | 1.1 – 4.3 | 0.024 |

| Body/Tail | Reference | ||

Discussion

This multi-institutional trial is a continuation of a series of studies at the University of Michigan which have utilized full dose gemcitabine with conformal radiation limited to gross tumor in localized pancreatic cancer11,13,18–20. The central tenet of this approach is that standard (full) doses of chemotherapy will maximize systemic disease control while simultaneously sensitizing the primary tumor to concurrent radiation12–15. This is in contrast to other gemcitabine/radiation combinations in which gemcitabine is given at lower doses (weekly 400–600 mg/m2, biweekly 40 mg/m2) and radiation includes clinically uninvolved lymph nodes9,10,21,22. In the current study, despite the addition of oxaliplatin at a standard dose, treatment was well tolerated with rates of hospitalization and non-hematologic grade 3–4 toxicities similar to, or lower than, previous studies9,10,19. While the primary study endpoint demonstrating an improvement in 2-year DFS was not achieved, principally due to entry of a majority of patients with borderline resectable disease, evidence of efficacy was noted. This therapy resulted in an R0 resection in 84% of surgically treated patients with a resultant median survival of 34.6 months; notable in the context that 70% of the resections were performed in borderline resectable (28 patients) or unresectable (2 patients) disease. Lymph nodes were involved in 49% of the resections, comparing favorably to a resectable patient population (72% in CONKO-1 and 66% in RTOG 97-04)3,4. This result, and a significant association of CA19-9 response and R0 resection, suggests treatment effect from preoperative therapy. For those achieving any resection, a median survival of 27.1 months is similar to the median survival reported in the adjuvant phase III trials2–4. Appreciating that preoperative treatment is commonly offered to patients with locally advanced disease, there is little prospective data for comparison to our trial, especially in borderline resectable disease19,23–25.

A persistent challenge to the development and evaluation of preoperative therapies for pancreatic cancer is accurate staging. In spite of evaluation in academic medical centers with multi-disciplinary pancreatic cancer programs, post-hoc central review of all CTs led to a number of patients’ resectability status being re-categorized in both directions, with 9 patients moved from borderline to resectable, and 14 patients upstaged, 8 from resectable to borderline and 6 to unresectable. This challenge of accurate staging is also reflected in changing definitions as occurred during the trial. The current definition of resectability is based on consensus statement published in 200926. Although we applied the 2008 definition throughout this report, using 2009 criteria to categorize our 68 evaluable patients, the number of resectable patients would decrease from 23 to 12, with 10 patients upstaged to borderline and 1 to unresectable.

The optimal time for surgery following neoadjuvant therapy is also difficult to define. The tumor may not regress on CT imaging despite clinical and CA 19-9 response27,28. Eight patients were removed from protocol due to vascular involvement to receive additional chemotherapy prior to surgery, and 5 subsequently had R0 resection. The observation that others in the trial with an increase in tumor LD (n=5) or with continuing contact on vessels following two cycles of treatment (n = 21) underwent R0 resections points to the difficulty in determining when an operation should be offered.

Several aspects of this report bear comment. The 2008 NCCN resectability criteria used were inadequate; while they clearly define resectable tumors, they did not easily distinguish between borderline and unresectable disease, especially for tumors outside the pancreatic head. The patient population was heterogeneous, with likelihood of resectablilty at baseline varied by tumor location within the pancreas and presence and degree of contact with vein(s) and/or arteries. The treatment protocol was intended for resectable patients per study design/endpoints and duration/intensity of preoperative therapy, yet eligibility criteria allowed patients with more advanced disease to be accrued. Finally, the utility of combination chemotherapy used here is uncertain. It was based on meta-analysis reporting survival benefit from gemcitabine-platin combinations in advanced disease, and might be supported by recent data with FOLFIRINOX29,30. The study, however, was not designed to determine the contribution of oxaliplatin to gemcitabine-based treatment.

Weaknesses of this study include difficulties in accurate characterization of resectability, entry of patients with unresectable disease, removal of patients from protocol to continue chemotherapy prior to surgery and lower number of patients that received adjuvant treatment. Strengths of this study include the multi-institutional setting, number of patients entered, especially with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer, and the central review of imaging, radiation treatment plan and pathology on resected specimens. This is one of the first prospective studies to establish what might be expected using current definitions of resectability in regards to R0 resection rates and overall outcomes.

In summary, we report on a group of 68 patients with localized pancreatic cancer that by 2009 definitions had resectable (12), borderline resectable (49), or unresectable disease (7)26. Following 2 cycles of preoperative chemotherapy with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin with radiation during cycle 1, a majority of patients went on to an R0 surgical resection. The median survival for the entire population was 18.2 months and for those achieving R0 resection 34.6 months. Based on this experience, the study treatment can be recommended for patients with resectable or borderline resectable disease. For those with more advanced disease, longer or more intensive chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy using higher doses should be further investigated31–33.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported (in part) by the National Institutes of Health through the University of Michigan’s Cancer Center Support Grant (5 P30 CA46592), by the use of the Cancer Center Clinical Trials Office and Biostatistics Core.

We thank Stephanie Gaulrapp, Helen Kim, KP Singh, and Barbara Kleiber for data management support.

Footnotes

Informed consent was obtained from the subjects and/or guardians prior to study participation.

This clinical trial has been registered with clinicaltrials.gov with registration identification # NCT00456599

Presented in part at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium, San Francisco, CA, January 20–21, 2011.

Funding disclosures: Dr. Zalupski received research support from Sanofi for this reported clinical trial. Dr. Bekaii-Saab receives support from Sanofi as a consultant. Dr. Wei has received honoraria from Sanofi.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 Jan-Feb;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010 Sep 8;304(10):1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007 Jan 17;297(3):267–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams RA, et al. Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008 Mar 5;299(9):1019–1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Piccoli A, Pedrazzoli S. Recurrence after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. World J Surg. 1997 Feb;21(2):195–200. doi: 10.1007/s002689900215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuhrman GM, Charnsangavej C, Abbruzzese JL, et al. Thin-section contrast-enhanced computed tomography accurately predicts the resectability of malignant pancreatic neoplasms. Am J Surg. 1994 Jan;167(1):104–111. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(94)90060-4. discussion 111-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pingpank JF, Hoffman JP, Ross EA, et al. Effect of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on surgical margin status of resected adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001 Mar-Apr;5(2):121–130. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurence JM, Tran PD, Morarji K, Eslick GD, Lam VW, Sandroussi C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of survival and surgical outcomes following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011 Nov;15(11):2059–2069. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1659-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans DB, Varadhachary GR, Crane CH, et al. Preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiation for patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jul 20;26(21):3496–3502. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varadhachary GR, Wolff RA, Crane CH, et al. Preoperative gemcitabine and cisplatin followed by gemcitabine-based chemoradiation for resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jul 20;26(21):3487–3495. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai SP, Ben-Josef E, Normolle DP, et al. Phase I study of oxaliplatin, full-dose gemcitabine, and concurrent radiation therapy in pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Oct 10;25(29):4587–4592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence TS, Chang EY, Hahn TM, Hertel LW, Shewach DS. Radiosensitization of pancreatic cancer cells by 2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxycytidine. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996 Mar 1;34(4):867–872. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)02134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGinn CJ, Zalupski MM, Shureiqi I, et al. Phase I trial of radiation dose escalation with concurrent weekly full-dose gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Nov 15;19(22):4202–4208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.22.4202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, et al. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005 May 20;23(15):3509–3516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan MA, Meirovitz A, Davis MA, Kollar LE, Hassan MC, Lawrence TS. Radiotherapy combined with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in pancreatic cancer cells. Transl Oncol. 2008 Mar;1(1):36–43. doi: 10.1593/tlo.07106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000 Feb 2;92(3):205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans DB, Rich TA, Byrd DR, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation and pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Arch Surg. 1992 Nov;127(11):1335–1339. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420110083017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muler JH, McGinn CJ, Normolle D, et al. Phase I trial using a time-to-event continual reassessment strategy for dose escalation of cisplatin combined with gemcitabine and radiation therapy in pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jan 15;22(2):238–243. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Small W, Jr, Berlin J, Freedman GM, et al. Full-dose gemcitabine with concurrent radiation therapy in patients with nonmetastatic pancreatic cancer: a multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 20;26(6):942–947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talamonti MS, Small W, Jr, Mulcahy MF, et al. A multi-institutional phase II trial of preoperative full-dose gemcitabine and concurrent radiation for patients with potentially resectable pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006 Feb;13(2):150–158. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blackstock AW, Tepper JE, Niedwiecki D, Hollis DR, Mayer RJ, Tempero MA. Cancer and leukemia group B (CALGB) 89805: phase II chemoradiation trial using gemcitabine in patients with locoregional adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2003;34(2–3):107–116. doi: 10.1385/ijgc:34:2-3:107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loehrer PJ, Sr, Feng Y, Cardenes H, et al. Gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine plus radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Nov 1;29(31):4105–4112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz MH, Pisters PW, Evans DB, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: the importance of this emerging stage of disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2008 May;206(5):833–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.020. discussion 846-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel M, Hoffe S, Malafa M, et al. Neoadjuvant GTX chemotherapy and IMRT-based chemoradiation for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2011 Aug 1;104(2):155–161. doi: 10.1002/jso.21954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stokes JB, Nolan NJ, Stelow EB, et al. Preoperative capecitabine and concurrent radiation for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011 Mar;18(3):619–627. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callery MP, Chang KJ, Fishman EK, Talamonti MS, William Traverso L, Linehan DC. Pretreatment assessment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009 Jul;16(7):1727–1733. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donahue TR, Isacoff WH, Hines OJ, et al. Downstaging chemotherapy and alteration in the classic computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging signs of vascular involvement in patients with pancreaticobiliary malignant tumors: influence on patient selection for surgery. Arch Surg. 2011 Jul;146(7):836–843. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz MH, Fleming JB, Bhosale P, et al. Response of borderline resectable pancreatic cancer to neoadjuvant therapy is not reflected by radiographic indicators. Cancer. 2012 May 17; doi: 10.1002/cncr.27636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011 May 12;364(19):1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sultana A, Smith CT, Cunningham D, Starling N, Neoptolemos JP, Ghaneh P. Meta-analyses of chemotherapy for locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Jun 20;25(18):2607–2615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Assifi MM, Lu X, Eibl G, Reber HA, Li G, Hines OJ. Neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis of phase II trials. Surgery. 2011 Sep;150(3):466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ben-Josef E, Schipper M, Francis IR, et al. A Phase I/II Trial of Intensity Modulated Radiation (IMRT) Dose Escalation With Concurrent Fixed-dose Rate Gemcitabine (FDR-G) in Patients With Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012 Apr 27; doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varadhachary GR, Tamm EP, Abbruzzese JL, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: definitions, management, and role of preoperative therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006 Aug;13(8):1035–1046. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]