Abstract

Background

The benefits and risks of prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy may be different for patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) compared with more stable presentations.

Objective

To assess the benefits and risks of 30 versus 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy among patients undergoing coronary stent implantation following presentation with and without MI.

Methods

The DAPT Study was a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing 30 versus 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting. The effect of continued thienopyridine on ischemic and bleeding events among patients initially presenting with versus without MI was assessed. The co-primary endpoints were definite or probable stent thrombosis and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE, a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke). The primary safety endpoint was GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding.

Results

Of 11,648 randomized patients (9961 treated with drug-eluting, 1687 with bare metal stents), 3,576 (30.7%) presented with MI. Between 12 and 30 months, continued thienopyridine reduced stent thrombosis compared with placebo in patients with and without MI at presentation (MI group 0.5% vs. 1.9%, hazard ratio [HR] 0.27, p<0.001; No MI group, 0.4% vs. 1.1%, HR 0.33, p<0.001; interaction p=0.69). The reduction in MACCE for continued thienopyridine was greater for patients with MI (3.9% vs. 6.8%, HR 0.56, p<0.001) compared to those with no MI (4.4% vs. 5.3%, HR 0.83, p=0.08, interaction p=0.03). In both groups, continued thienopyridine reduced MI (2.2% vs. 5.2%, HR 0.42, p<0.001 for MI; 2.1% vs. 3.5%, HR 0.60, p<0.001 for no MI, interaction p=0.15) but increased bleeding (1.9% vs. 0.8%, p=0.005 for MI; 2.6% vs. 1.7%, p=0.007 for no MI; interaction p = 0.21).

Conclusions

Compared with 12 months of therapy, 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy reduced the risk of stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction in patients with and without MI, and increased bleeding.

Keywords: Antiplatelet therapy, acute coronary syndromes, myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, randomized clinical trial

Introduction

Treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy using the combination of a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor and aspirin is mandatory after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stents. In the Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (DAPT) Study, patients who were free from major ischemic or bleeding events at 1 year after PCI had significant reductions in stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction but increases in moderate or severe bleeding when treated with continued dual antiplatelet therapy for a total of 30 months as compared with 12 months.(1) Patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction (MI) may derive particular benefit from treatment with extended duration dual antiplatelet therapy, due to a greater risk of subsequent myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis.(2,3) Consequently, current guidelines generally recommend a longer treatment period in patients undergoing PCI for MI regardless of stent type (bare metal or drug-eluting) compared with those undergoing PCI for less acute indications. (4–6)

However, patients with stable coronary disease are also at risk for future acute ischemic events, and may also benefit from prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy. (7) Whether those undergoing PCI for MI derive a similar or greater benefit from continued thienopyridine treatment beyond 12 months compared with those undergoing PCI for more stable presentations is unknown. We therefore compared the treatment effect of 30 vs. 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting among subjects who presented with and without acute MI.

METHODS

Design

The DAPT Study design has previously been described.(8) Briefly, this double-blind, international, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial compared the benefits and risks of 30 versus 12 months of thienopyridine therapy (clopidogrel or prasugrel) when prescribed in addition to aspirin following coronary stenting with either drug-eluting stents (DES) or bare metal stents (BMS) (ClinicalTrials.gov # NCT00977938). The trial incorporated five individual component studies into a single, uniform randomized trial, with enrollment of subjects either by the Harvard Clinical Research Institute (HCRI) or through one of four post-marketing surveillance studies. The results comparing randomized treatments in the overall DES-treated(1) and BMS-treated(9) cohorts have been reported previously. The institutional review board at each participating institution approved the study. The purpose of the present study was to examine whether the ischemic benefits and bleeding risks associated with 30 versus 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy are consistent among patients presenting with versus without acute MI.. These analyses were not prespecified in the original protocol.

Study Population and Procedures

We enrolled patients with coronary artery disease who were candidates for dual antiplatelet therapy and who received treatment with Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved DES and BMS devices. Patients provided written informed consent and were enrolled within 3 days of stent placement. Stent treatment was performed according to site standards of care. DES types included sirolimus-eluting stent (Cypher, Cordis), zotarolimus-eluting stent (Endeavor, Medtronic), paclitaxel-eluting stent (TAXUS, Boston Scientific), and everolimus-eluting stents (Xience, Abbott Vascular; PROMUS, Boston Scientific). For this analysis, all randomized DES- and BMS-treated patients were included.

All patients received open-label aspirin plus thienopyridine for the first 12 months after stent implantation. In one of the contributing studies(10), all patients received prasugrel under an Investigational Device Exemption from the FDA. In the remaining four contributing studies, the selection of thienopyridine was left to the discretion of the treating physician. At 12 months, patients who had not had a major adverse cardiovascular or cerebrovascular event (MACCE, defined as the composite of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke), repeat revascularization, or moderate or severe bleeding and had been compliant with thienopyridine therapy (defined as having taken 80 to 120% of the drug without an interruption of longer than 14 days) were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to continued thienopyridine or to placebo for an additional 18 months. Both groups continued aspirin therapy.

Computer-generated randomization was stratified according to stent type (DES vs. BMS), hospital site, thienopyridine type, and presence or absence of at least one prespecified clinical- or lesion-related stent thrombosis risk factors, including presentation with MI. (8) Acute MI at the time of PCI was defined as the presence of ischemic symptoms at rest and lasting > 10 minutes before index procedure and/or EKG evidence of ischemia, in conjunction with elevated levels of a cardiac biomarker of necrosis (CK-MB or troponin T or I greater than the upper limit of normal). If CK-MB or troponin was not available, total CK >2 times the upper limit of normal was also considered to constitute MI.

Endpoints

The co-primary effectiveness end points of the DAPT Study were the incidence of definite or probable stent thrombosis according to the Academic Research Consortium definitions(11) and incidence of MACCE in all randomized patients at 12– 30 months post-index procedure. The primary safety endpoint was moderate or severe bleeding during this same time period as assessed according to the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Arteries [GUSTO] classification.(12) Bleeding was also ascertained according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] definitions.(13) Secondary endpoints of the study included MI, according to the ARC definition, which was further segregated into those occurring in association with stent thrombosis and those not related to stent thrombosis.

All potential endpoint events were adjudicated by an independent Clinical Events Committee blinded to treatment assignment. An independent central Data Safety Monitoring Board reviewed data from all subjects at regular intervals.

Statistical Analysis

We compared Kaplan-Meier estimates of endpoint events occurring between 12 and 30 months after PCI among patients with and without acute MI at presentation, irrespective of treatment arm using the log-rank test. Patients not experiencing the co-primary endpoints 12–30 months post-index procedure were censored at the time of last known contact or 30 months, whichever was earlier.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of endpoint events were also generated for each treatment arm among patients with and without MI. The effects of continued thienopyridine vs. placebo for patients with and without MI were assessed using Cox-proportional hazards regression models, and are expressed as hazard ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The consistency of the treatment effect between patients with and without MI was evaluated through the inclusion of randomized treatment-by-MI status interaction terms. Furthermore, among patients with and without MI, exploratory sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the consistency of treatment effect among DES- vs. BMS-treated patients for stent thrombosis, and among patients treated with clopidogrel vs. prasugrel at randomization for stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and bleeding. Finally, for the endpoints of stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction, additional analyses were performed excluding paclitaxel-eluting stents, which have been associated with higher rates of adverse stent-related ischemic events compared with other drug-eluting stents.(14)

All analyses were performed on randomized subjects according to the intention-to-treat principle. All statistical analyses were conducted at HCRI with the use of SAS software, version 9.2. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A two-sided p value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Role of the funding source

The stent manufacturers who funded the trial had contributing roles in the design of the trial and in the collection of the data. HCRI was responsible for the scientific conduct of the trial and independent analysis of the data. RWY, JMM and LM had full access to all the data used in the study, and the study publications committee (including RWY, DJK, JMM, and LM) had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Study Population

Of 11,648 patients randomized in the DAPT Study, 3,576 (30.7%) presented with acute MI with the remainder presenting without evidence of MI at the index procedure. (Figure 1) Among MI patients, 1680 (47%) presented with initial ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), while the remainder presented with non-STEMI. Among patients with no MI, 1821 (22.6%) were classified as having unstable angina without cardiac biomarker elevation.

Figure 1. Enrollment, randomization and follow-up of patients in the DAPT Study stratified by acute myocardial infarction status at presentation.

Patients were enrolled within 72 hours after placement of either a bare metal or drug-eluting stent, and received open-label treatment with aspirin and thienopyridine. Eligible subjects were then randomized to thienopyridine or placebo, while continuing aspirin, and followed for an additional 18 months (months 12–30).

Patients with MI had higher rates of smoking while patients with no MI were older (average age 63 vs. 58 years, p<0.001), more often female, and had higher rates of diabetes, peripheral arterial disease and prior PCI. Characteristics were evenly balanced across randomization arms for patients with and without MI. (Table 1) Rates of prasugrel use at randomization were higher among patients with MI compared to those without (34.0% vs. 30.6%, respectively, p<0.001). Among patients with MI, 27.6% received BMS only and 72.4% received a DES, compared with 8.7% and 91.3%, respectively, among patients with no MI. Lesions were less complex among patients with MI, with lower rates of heavy calcification, tortuosity, left main and in-stent restenosis lesions.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of randomized patients initially presenting with versus without acute myocardial infarction

| Myocardial Infarction at Presentation (N=3576) |

No Myocardial Infarction at Presentation (N=8072) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Thienopyridine N=1805 |

Placebo N=1771 |

Thienopyridine N=4057 |

Placebo N=4015 |

| Patients | ||||

| Age (years) | 57.9 ± 10.5 | 57.7 ± 10.5 | 63.0 ± 9.8 | 62.8 ± 9.8 |

| Female | 22.4% | 21.2% | 25.9% | 27.2% |

| Non-White race | 8.9% | 7.9% | 8.6% | 8.7 |

| Weight (kg) | 89.7 ±19.1 | 90.8 ± 19.0 | 91.6 ± 19.8 | 91.2 ± 19.5 |

| BMI | 29.8 ± 5.5 | 30.0 ± 5.6 | 30.7 ± 5.8 | 30.6 ± 5.8 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20.8% | 21.0% | 33.7% | 32.1% |

| Hypertension | 59.8% | 56.4% | 80.5% | 79.7% |

| Cigarette smoker | 41.8% | 41.8% | 21.0% | 21.0% |

| Stroke or TIA | 2.1% | 2.5% | 4.0% | 4.0% |

| Congestive heart failure | 3.0% | 2.9% | 5.4% | 5.0% |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 2.6% | 3.2% | 6.8% | 7.0% |

| Prior PCI | 16.4% | 15.4% | 34.0% | 35.7% |

| Prior CABG | 4.1% | 5.5% | 13.4% | 13.3% |

| Prior myocardial Infarction | 19.1% | 20.0% | 22.8% | 21.7% |

| Indication for PCI | ||||

| Myocardial Infarction | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| STEMI | 46.8% | 47.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| NSTEMI | 53.2% | 52.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Unstable Angina | 0.0% | 0.0% | 22.6% | 22.6% |

| Stable Angina | 0.0% | 0.0% | 51.3% | 51.5% |

| Other | 0.0% | 0.0% | 26.2% | 25.9% |

| Any risk factor for stent thrombosis† | 100.0% | 100.0% | 31.1% | 31.7% |

| Renal Insufficiency or Failure | 3.5% | 2.6% | 4.7% | 4.3% |

| LVEF < 30% | 2.6% | 2.0% | 1.8% | 1.7% |

| More than 2 vessels stented | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.6% |

| More than 2 lesions per vessel | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.8% | 2.0% |

| Lesion length ≥ 30 mm | 10.2% | 8.8% | 9.2% | 10.0% |

| Bifurcation lesion | 5.6% | 6.2% | 6.5% | 6.2% |

| In-stent restenosis of DES | 1.4% | 1.4% | 3.3% | 3.5% |

| Vein graft stented | 1.7% | 2.4% | 2.9% | 3.2% |

| Unprotected left main stented | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% |

| Thrombus-containing lesion | 37.4% | 35.1% | 3.7% | 4.0% |

| Prior brachytherapy | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Thienopyridine at randomization | ||||

| Clopidogrel | 66.4% | 65.6% | 69.2% | 69.5% |

| Prasugrel | 33.6% | 34.4% | 30.8% | 30.5% |

| DES | 72.4% | 91.3% | ||

| Type of DES at index procedure | ||||

| Sirolimus | 8.3% | 7.8% | 12.6% | 12.1% |

| Zotarolimus | 12.0% | 11.4% | 13.1% | 13.0% |

| Paclitaxel | 28.3% | 30.2% | 26.4% | 25.4% |

| Everolimus | 49.8% | 48.5% | 45.6% | 47.5% |

| >1 type | 1.6% | 2.1% | 2.3% | 2.1% |

| No. of treated lesions | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.5 |

| No. of treated vessels | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| No. of stents | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.7 |

| Minimum stent diameter | ||||

| <3 mm | 37.2% | 37.3% | 46.1% | 45.8% |

| ≥3 mm | 62.8% | 62.7% | 53.9% | 54.2% |

| Total stent length- mm | 27.6 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 26.9 |

| Lesions | N=2259 | N=2207 | N=5310 | N=5197 |

| Treated vessel | ||||

| Native coronary-artery lesions | 98.0% | 97.2% | 96.8% | 96.8% |

| Left main | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.9% | 0.9% |

| Left anterior descending | 36.7% | 34.5% | 41.4% | 41.1% |

| Right | 38.6% | 38.3% | 32.4% | 32.1% |

| Circumflex | 22.4% | 24.1% | 22.1% | 22.8% |

| Venous graft | 1.7% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.7% |

| Arterial graft | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.6% | 0.5% |

| In-stent restenosis | 1.9% | 1.5% | 4.0% | 4.4% |

| Extreme tortuosity | 3.1% | 2.9% | 4.8% | 3.9% |

| Heavy calcification | 5.8% | 4.9% | 9.3% | 8.5% |

| Modified ACC or AHA lesion class B2 or C | 52.9% | 53.9% | 40.2% | 39.4% |

Stent thrombosis risk factors include those listed as well as presentation with acute myocardial infarction at index procedure.

Abbreviations: ACC, American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DES, drug-eluting stent; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Results presented are mean (SD) for continuous variables and percent for categorical variables.

Outcomes Comparing Patients With vs. Without Acute MI

Patients with presenting with MI had significantly higher rates of definite or probable stent thrombosis (1.2% vs. 0.7%, p=0.01) between 12–30 months than patients without MI. Rates of MACCE were similar for patients with vs. without MI (5.4% vs. 4.9%, p=0.24). Among the components of MACCE, rates of recurrent myocardial infarction were higher for patients with MI compared with those without MI (3.7% vs. 2.8%, p=0.01) (Figure 2B), which was primarily related to higher rates of stent-thrombosis-associated myocardial infarction (1.2% vs. 0.7%, p = 0.005). The rates of death and stroke were no different between patients with vs. without MI. In both groups, non-fatal MI was the predominant contributor to MACCE in follow-up, accounting for 69% of events in the MI group, and 57% of events in no MI group.

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence of stent thrombosis according to randomization arm for patients with (Panel A) and without (Panel B) acute myocardial infarction.

Randomization occurred 12 months after initial presentation. Endpoint includes definite or probable stent thrombosis as assessed according to the criteria of the Academic Research Consortium. The effect of continued thienopyridine on stent thrombosis was similar for patients with vs. without myocardial infarction at presentation (interaction p=0.69).

GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding occurred less often in patients with MI (1.4%) as compared with those without (2.1%, p=0.008) between 12–30 months after initial presentation. Similar results were observed based on classification by the BARC-definitions. Fatal bleeding was rare and not significantly different between patients with vs. without MI (0.17% vs. 0.08%, p=0.145).

Consistency of Treatment Effect of Continued Thienopyridine in Patients Presenting With and Without MI

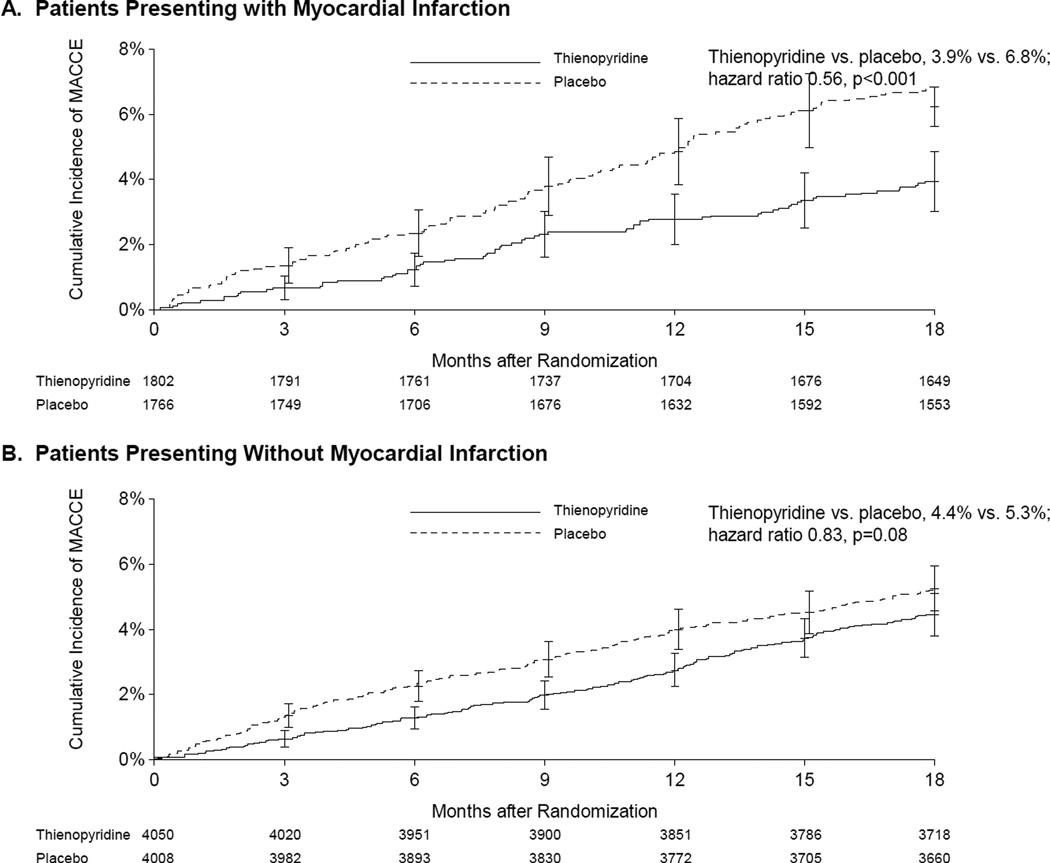

The relative reduction of stent thrombosis associated with continued thienopyridine was similar for patients with and without MI (interaction p=0.69 for stent thrombosis (Figures 2) In patients with MI, the rate of stent thrombosis was 0.5% for continued thienopyridine versus 1.9% for placebo (hazard ratio [HR] 0.27, 95% CI 0.13–0.57, p<0.001), while for patients with no MI, the corresponding rates were 0.4% versus 1.1%, respectively (HR 0.33, 95% CI 0.18–0.60, p<0.001). For the composite endpoint of MACCE, continued thienopyridine was associated with a similar directional benefit but greater magnitude reductions for patients with MI (3.9% vs. 6.8%, HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.42–0.76, p<0.001) compared with those without MI (4.4% vs. 5.3%, HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.68–1.02, p=0.08, interaction p=0.03). (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Cumulative incidence of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) according to randomization arm for patients with (Panel A) and without (Panel B) acute myocardial infarction.

MACCE was defined as the composite of death, myocardial infarction or stroke. Randomization occurred 12 months after initial presentation. The effect of continued thienopyridine on MACCE was greater for patients with MI compared with patients without myocardial infarction at presentation (interaction p=0.03).

Continued thienopyridine consistently reduced myocardial infarction in patients with and without MI (interaction p=0.15, Figure 4/Central Figure). Among patients with MI, the rate of myocardial infarction was 2.2% for continued thienopyridine versus 5.2% for placebo (HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.29–0.62, p<0.001). In patients with no MI, the rate of myocardial infarction was 2.1% for continued thienopyridine vs. 3.5% for placebo (HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.45–0.79, p<0.001). For both groups, the reduction in myocardial infarction was related to the prevention of both stent thrombosis and non-stent thrombosis-related events. (Table 3)

Figure 4. Cumulative incidence of myocardial infarction according to randomization arm for patients with (Panel A) and without (Panel B) acute myocardial infarction.

Randomization occurred 12 months after initial presentation. The effect of continued thienopyridine on myocardial infarction was similar for patients with vs. without myocardial infarction at presentation (interaction p=0.15).

Table 3.

Ischemic and bleeding outcomes 12–30 months after coronary stent treatment in all randomized patients, stratified by presentation with versus without acute myocardial infarction.

| Continued Thienopyridine N (%) |

Placebo N (%) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

Stratified Log- Rank P Value |

P Value for Interaction |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definite or Probable Stent Thrombosis | 0.69 | ||||

| MI Group | 9 (0.5%) | 32 (1.9%) | 0.27 (0.13,0.57) | <0.001 | |

| No MI Group | 14 (0.4%) | 42 (1.1%) | 0.33 (0.18,0.60) | <0.001 | |

| MACCE | 0.03 | ||||

| MI Group | 69 (3.9%) | 117 (6.8%) | 0.56 (0.42,0.76) | <0.001 | |

| No MI Group | 175 (4.4%) | 206 (5.3%) | 0.83 (0.68,1.02) | 0.08 | |

| MI | 0.15 | ||||

| MI Group | 39 (2.2%) | 88 (5.2%) | 0.42 (0.29,0.62) | <0.001 | |

| No MI Group | 82 (2.1%) | 135 (3.5%) | 0.60 (0.45,0.79) | <0.001 | |

| Stent Thrombosis-Related MI | 0.86 | ||||

| MI Group | 9 (0.5%) | 32 (1.9%) | 0.27 (0.13,0.57) | <0.001 | |

| No MI Group | 12 (0.3%) | 40 (1.0%) | 0.30 (0.16,0.57) | <0.001 | |

| Non-Stent Thrombosis-Related MI | 0.24 | ||||

| MI Group | 31 (1.8%) | 56 (3.3%) | 0.53 (0.34,0.83) | 0.01 | |

| No MI Group | 73 (1.9%) | 98 (2.5%) | 0.74 (0.54,1.00) | 0.047 | |

| Death | 0.13 | ||||

| MI Group | 24 (1.4%) | 27 (1.6%) | 0.87 (0.50,1.50) | 0.61 | |

| No MI Group | 82 (2.1%) | 57 (1.5%) | 1.43 (1.02,2.00) | 0.04 | |

| Cardiac Death | 0.33 | ||||

| MI Group | 11 (0.6%) | 16 (0.9%) | 0.67 (0.31,1.44) | 0.30 | |

| No MI Group | 38 (1.0%) | 36 (0.9%) | 1.05 (0.66,1.65) | 0.48 | |

| Non-Cardiovascular Death | 0.23 | ||||

| MI Group | 11 (0.6%) | 9 (0.5%) | 1.19 (0.49,2.87) | 0.69 | |

| No MI Group | 41 (1.0%) | 18 (0.5%) | 2.26 (1.30,3.94) | 0.002 | |

| GUSTO Moderate or Severe Bleeding | 0.21 | ||||

| MI Group | 34 (1.9%) | 14 (0.8%) | 2.38 (1.27,4.43) | 0.005 | |

| No MI Group | 101 (2.6%) | 66 (1.7%) | 1.53 (1.12,2.08) | 0.007 | |

| GUSTO Moderate Bleeding | 0.06 | ||||

| MI Group | 21 (1.2%) | 5 (0.3%) | 4.10 (1.55,10.87) | 0.002 | |

| No MI Group | 70 (1.8%) | 47 (1.2%) | 1.48 (1.03,2.15) | 0.04 | |

| GUSTO Severe Bleeding | 0.86 | ||||

| MI Group | 13 (0.7%) | 9 (0.5%) | 1.41 (0.60,3.29) | 0.43 | |

| No MI Group | 31 (0.8%) | 20 (0.5%) | 1.54 (0.88,2.70) | 0.13 | |

| BARC 2, 3 or 5 | 0.666 | ||||

| MI Group | 76 (4.3%) | 35 (2.1%) | 2.14 (1.43,3.19) | <0.001 | |

| No MI Group | 223 (5.7%) | 116 (3.0%) | 1.93 (1.55,2.42) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: MI, myocardial infarction; GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Arteries; MACCE, major adverse cerebral and cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; NNH, number needed to harm; NNT, number needed to treat.

Percentages are Kaplan–Meier estimates.

Continued thienopyridine increased major bleeding in both patients with MI (1.9% vs. 0.8%, hazard ratio 2.38, 95% CI 1.28–4.43, p=0.005) and those without MI (2.6% vs. 1.7%, hazard ratio 1.53, 95% CI 1.12–2.08, p=0.007, p=0.21 for interaction). Among patients with MI, the rates of all-cause death were 1.4% in the continued therapy group vs. 1.6% in the placebo group (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.50–1.50, p=0.61). Among patients with no MI, the rates of death were 2.1% for continued thienopyridine group vs. 1.5% for placebo (HR 1.43, 95% CI 1.02–2.00, p=0.04, effect for MI vs. no MI interaction p=0.13).

Sensitivity analyses

In patients with and without MI, reduction in stent thrombosis with continued thienopyridine was consistent for DES-treated patients and BMS-treated patients (interaction p=0.87 for MI patients; interaction p=0.12 for no MI patients) (Supplementary Materials) Continued thienopyridine was also associated with consistent reductions in stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction across different thienopyridine types, prasugrel and clopidogrel, (interaction p = 0.86 for stent thrombosis, p = 0.22 for myocardial infarction for patients with MI; interaction p = 0.96 for stent thrombosis, p = 0.10 for myocardial infarction for patients without MI). Moderate or severe bleeding with continued thienopyridine was also increased to a similar degree with prasugrel or clopidogrel among patients with MI (interaction p = 0.09) and those without MI (interaction p = 0.33). Finally, when excluding patients who received paclitaxel eluting-stents, the results were similar to the main study findings, with continued thienopyridine having a similar effect on stent thrombosis (interaction p=0.36) and myocardial infarction (interaction p=0.36) for patients with and without MI.

DISCUSSION

In this analysis from the DAPT Study, patients presenting with acute MI who survived the first year after PCI without a major ischemic or bleeding event continued to be at higher risk for subsequent ischemic events, including stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction, compared with those presenting without MI. Continued thienopyridine therapy beyond 12 months was associated with significant reductions in stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction and an increase in bleeding in both groups.

These findings have important implications for the management of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing PCI. As demonstrated here and in prior studies, patients presenting with MI represent a subgroup that continues to experience higher rates of stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction more than 1 year removed from their initial event.(2) As such, MI patients are among those that may derive particular benefit from extension of thienopyridine therapy. Current guidelines recommend only a year of dual antiplatelet therapy after an acute coronary event.(4–6) Our data suggest that if patients undergoing PCI after MI have not experienced a major ischemic or bleeding event within the first year of follow up, continuation of dual antiplatelet therapy beyond one year is associated with a reduced risk of stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction. Continued thienopyridine therapy over an 18 month treatment period was associated with an absolute risk reduction of 2.9% for myocardial infarction and 1.4% for stent thrombosis, and an absolute risk increase of 1.1% for moderate or severe bleeding (0.9% for moderate and 0.2% for severe) among patients with MI.

Patients undergoing PCI without MI had lower long-term ischemic event rates compared with MI patients, yet the reduction in stent thrombosis and MI with continued dual antiplatelet therapy was consistent among patients not presenting with MI. Compared with 12 months of treatment, continued thienopyridine therapy over an 18 month treatment period was associated with an absolute risk reduction of 1.4% for myocardial infarction and 0.7% for stent thrombosis, and an absolute risk increase of 0.9% for moderate or severe bleeding (0.6% for moderate and 0.3% for severe) in this population.

A lesser magnitude reduction in MACCE was observed with continued thienopyridine therapy among patients without compared to those with MI at presentation, due in part to the overall lower rates of non-fatal MI in follow up among patients without MI, but also to an increase in death for patients without MI receiving continued dual antiplatelet therapy. As previously described(1), a higher rate of non-cardiovascular death was observed among drug-eluting stent-treated patients assigned to continued thienopyridine. Blinded adjudication of all-non-cardiovascular deaths determined that the large majority of these deaths were not preceded by a documented bleeding event. A meta-analysis of over 69,000 patients from randomized clinical trials comparing different durations of dual antiplatelet therapy across a variety of clinical indications, including more than 39,000 patients with coronary artery disease, showed no association between thienopyridine therapy and all-cause or non-cardiovascular death(15), suggesting that the findings among drug-eluting stent patients, concentrated among those without MI, may have been due to chance. Patients without MI were older and had more comorbidities (diabetes, peripheral and cerebrovascular disease). These factors may have led to the higher proportion of non-cardiac events in patients without MI; it is also possible that these factors contributed to more frequent bleeding events in this same group.

In light of greater reduction in quality of life expectancy associated with major ischemic events, as compared with bleeding events of this frequency and magnitude(16), our results suggest that among acute MI patients undergoing PCI, there is a strong benefit for continuing thienopyridine therapy beyond 12 months after presentation. However, even among patients without MI, the risk-benefit balance may favor continuation of thienopyridine therapy beyond 12 months for those who are able to tolerate the first year of dual antiplatelet therapy. The results also suggest that the benefits of continued thienopyridine therapy observed in patients with and without MI were consistent whether or not patients received clopidogrel or prasugrel, or whether they received paclitaxel or non-paclitaxel-eluting stents. Furthermore, the benefit of receiving continued thienopyridine therapy in patients with and without MI was in the prevention of non-fatal MI in follow up, both related to and not related to stent thrombosis. The absolute reduction in non-stent thrombosis-related MI was 1.5% in the MI group and 0.6% in the no MI group, accounting for roughly half of the reduction in non-fatal MI in both groups. These findings suggest that continued thienopyridine therapy has an important effect beyond stent thrombosis on secondary prevention of future MIs after PCI.

A number of prior analyses have compared different durations of dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stent procedures(17–21) including examining the consistency of treatment effects on patients with and without acute coronary syndromes.(22) However, the DAPT Study is unique in several regards. First, it is the largest study to date, having been powered to examine rare events such as stent thrombosis. Next, patients enrolled in the DAPT Study comprised a broad range of presentations(23), including a very high proportion with acute coronary syndromes, including STEMI, allowing more precise estimates of the effect of continued thienopyridine therapy in high-risk patients similar to those seen in clinical practice. The study population represents the largest cohort to date to evaluate the effect of continued thienopyridine therapy after coronary stents in patients with and without MI..

Beyond randomized studies focused on coronary stents, the largest prior study of extended duration clopidogrel in subjects with symptomatic, but stable, cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease was negative regarding reduction in cardiovascular risk. (7) Within this trial, the subset of patients with prior documented symptomatic cardiovascular disease (mainly coronary artery disease) appeared to benefit from extended therapy(24), whereas the asymptomatic subset did not. Our results are consistent with these prior results, and suggest that among symptomatic patients with coronary artery disease, prolonged thienopyridine therapy may provide ischemic benefit. Notably, in the DAPT Study, subjects without MI represented a higher risk population than subjects studied in prior trials of stable angina, as the group included a large number of subjects with unstable angina, all with history of prior coronary revascularization procedures, and with concomitant cardiac risk factors.

These findings suggest that patients previously considered “stable”, a full year removed from PCI for acute or stable presentations, are still subject to preventable risks of future MI, not directly related to the stent procedure. The one-year follow up after coronary stenting thus provides an important contact in which to intervene to continue thienopyridine therapy in those subjects who have tolerated treatment without major bleeding.

Several limitations should be considered in interpreting this analysis. First, because the study randomized only those patients who did not sustain a major event during the first year after PCI and were compliant with therapy, the study results are only relevant to patients who have achieved a similar milestone. Next, the study only included thienopyridine P2Y12 inhibitors; a related randomized study of a different P2Y12 inhibitor, ticagrelor, will identify whether subjects with prior MI benefit from extended dual antiplatelet therapy initiation with this agent.(25) We conducted several exploratory analyses examining the consistency of the treatment effect of continued thienopyridine based on stent type and drug type. However, these analyses were not pre-specified nor specifically powered to assess interactions, and should therefore be interpreted accordingly. Finally, the results shown represent aggregated findings for patients with and without MI. Additional risk factors may help to identify smaller subgroups of patients who may experience a different balance in the risks and benefits of continued thienopyridine therapy after 12 months.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the continuation of thienopyridine-plus-aspirin therapy beyond 1 year after coronary stenting reduced ischemic events in patients both with and without acute MI at presentation, but increased bleeding compared with treatment with aspirin alone. Although patients presenting with MI had higher risks of subsequent ischemic events, the effect of continued treatment in reducing stent thrombosis and MI was nevertheless consistent among patients not presenting with MI.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Ischemic and bleeding outcomes in all randomized patients, according to acute myocardial infarction status, from 12–30 months after stent implantation.

| Outcome | Myocardial Infarction at Presentation N=3576 |

No Myocardial Infarction at Presentation N=8072 |

Log-rank P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stent Thrombosis (Definite or Probable) | 41 (1.19%) | 56 (0.72%) | 0.01 |

| Definite | 39 (1.14%) | 47 (0.60%) | 0.003 |

| Probable | 3 (0.09%) | 9 (0.12%) | 0.67 |

| MACCE (Death, MI, or Stroke) | 186 (5.37%) | 381 (4.85%) | 0.24 |

| Death | 51 (1.48%) | 139 (1.77%) | 0.26 |

| Cardiac | 27 (0.78%) | 74 (0.95%) | 0.39 |

| Vascular | 4 (0.12%) | 6 (0.08%) | 0.52 |

| Non-Cardiovascular | 20 (0.58%) | 59 (0.76%) | 0.31 |

| MI | 127 (3.69%) | 217 (2.78%) | 0.010 |

| Stent Thrombosis Related | 41 (1.19%) | 52 (0.67%) | 0.005 |

| Non Stent Thrombosis Related | 87 (2.52%) | 171 (2.19%) | 0.27 |

| Stroke (total) | 25 (0.73%) | 66 (0.85%) | 0.51 |

| Ischemic | 19 (0.55%) | 48 (0.62%) | 0.69 |

| Hemorrhagic | 7 (0.20%) | 16 (0.21%) | 0.99 |

| Type Uncertain | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (0.03%) | 0.35 |

| GUSTO Moderate or Severe Bleeding | 48 (1.39%) | 167 (2.14%) | 0.008 |

| GUSTO Moderate | 26 (0.75%) | 117 (1.50%) | 0.001 |

| GUSTO Severe | 22 (0.64%) | 51 (0.66%) | 0.93 |

| BARC Types 2, 3, or 5 | 111 (3.22%) | 339 (4.34%) | 0.005 |

| BARC Type 2 | 61 (1.77%) | 185 (2.37%) | 0.04 |

| BARC Type 3 | 47 (1.36%) | 165 (2.12%) | 0.007 |

| BARC Type 5 (fatal bleeding) | 6 (0.17%) | 6 (0.08%) | 0.15 |

Abbreviations: GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Arteries; MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction.

Percentages are Kaplan Meier estimates.

Perspectives.

Competency in Systems-Based Practice

Continuation of thienopyridine therapy beyond 12 months after coronary stent implantation significantly reduces stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction in patients presenting initially with myocardial infarction as well as those with more stable disease, but increases bleeding.

Translational Outlook

Because continuation of dual antiplatelet therapy reduces ischemic events but also increases bleeding, patients should be made aware of the respective risks they incur and be involved in the decision to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond one year after coronary stent implantation.

Acknowledgments

This research has been sponsored by Harvard Clinical Research Institute and funded by Abbott, Boston Scientific Corporation, Cordis Corporation, Medtronic, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb Company/Sanofi Pharmaceuticals Partnership, Eli Lilly and Company, and Daiichi Sankyo Company Limited and the US Department of Health and Human Services (1RO1FD003870-01).

The authors wish to acknowledge Ms. Priscilla Driscoll-Schempp, Ms. Wen-Hua Hsieh, and Ms. Joanna Suomi for their important contributions to this study.

Dr. Yeh: Advisory Board – Abbott Vascular; Consulting Fees – Gilead Sciences, Merck

Dr. Steg: Personal fees from Amarin, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Merck-Sharpe-Dohme, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Medtronic, sanofi-aventis, Servier, Vivus, Janssn, The Medicines Company, and Orexigen; and grants from sanofi-aventis and Servier.

Dr. Windecker: Research grants to the institution from Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Medicines Company and St Jude, and speaker fees from Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Bayer and Biosensors.

Dr. Gershlick: Personal fees from Medtronic, personal fees from Abbott, grants from Medicines Company

Dr. Cutlip: Other fees from Medtronic, other from Boston Scientific, other from Cordis Inc., other from Abbott Vascular, grants from NHLBI, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Cohen: Research grant support to institution – Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Medtronic; Consulting Fees – Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Abbott Vascular, Medtronic

Dr. Tanguay: Personal fees and other from Abbott Vascular, personal fees and other from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees and other from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees and other from Eli Lilly, personal fees and other from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Roche, personal fees and other from Sanofi-Aventis, personal fees from Servier, other from Ikaria, other from Merck

Dr. Wiviott: grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, grants from Eisai, grants and personal fees from Arena, grants from Merck, personal fees from Aegerion, personal fees from Angelmed, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Xoma, personal fees from ICON Clinical, personal fees from Boston Clinical Research Institute, grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly/Daiichi Sankyo, grants from Sanofi-Aventis, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Massaro: Personal fees from Harvard Clinical Research Institute during the conduct of the study

Dr. Mauri: Institutional research grants from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Eli Lilly/Daiichi Sankyo, and sanofi Aventis/Bristol Myers Squibb; and personal fees from Medtronic, Recor, St. Jude Medical, and Biotronik.

Abbreviations

- ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

- ARC

Academic Research Consortium

- BARC

Bleeding Academic Research Consortium

- BMS

Bare metal stent

- DAPT Study

Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Study

- DES

Drug-eluting stent

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GUSTO

Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Arteries

- MACCE

Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

- MI

Myocardial Infarction

- PCI

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00977938

Relationships with Industry:

Dr. Kereiakes: None

Dr. Rinaldi: None

Dr. Jacobs: None

Dr. Iancu: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, et al. Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371:2155–2166. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jernberg T, Hasvold P, Henriksson M, Hjelm H, Thuresson M, Janzon M. Cardiovascular risk in post-myocardial infarction patients: nationwide real world data demonstrate the importance of a long-term perspective. European heart journal. 2015 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu505. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Werkum JW, Heestermans AA, Zomer AC, et al. Predictors of coronary stent thrombosis: the Dutch Stent Thrombosis Registry. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;53:1399–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Authors/Task Force m. Windecker S, Kolh P, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) European heart journal. 2014;35:2541–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58:e44–e122. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanguay JF, Bell AD, Ackman ML, et al. Focused 2012 update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the use of antiplatelet therapy. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2013;29:1334–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;354:1706–1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Normand SL, et al. Rationale and design of the dual antiplatelet therapy study, a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial to assess the effectiveness and safety of 12 versus 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy in subjects undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with either drug-eluting stent or bare metal stent placement for the treatment of coronary artery lesions. American heart journal. 2010;160:1035–1041. 1041 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Massaro JM, et al. Antiplatelet therapy duration following bare metal or drug-eluting coronary stents: the Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1671. (accepted for publication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garratt KN, Weaver WD, Jenkins RG, et al. Prasugrel plus aspirin beyond 12 months is associated with improved outcomes after taxus liberte Paclitaxel-eluting coronary stent placement. Circulation. 2015;131:62–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. The GUSTO investigators. The New England journal of medicine. 1993;329:673–682. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309023291001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmerini T, Biondi-Zoccai G, Della Riva D, et al. Stent thrombosis with drug-eluting and bare-metal stents: evidence from a comprehensive network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:1393–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elmariah S, Mauri L, Doros G, et al. Extended duration dual antiplatelet therapy and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62052-3. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg P, Galper BZ, Cohen DJ, Yeh RW, Mauri L. Balancing the risks of bleeding and stent thrombosis: A decision analytic model to compare durations of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. American heart journal. 2015;169:222–233 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collet JP, Silvain J, Barthelemy O, et al. Dual-antiplatelet treatment beyond 1 year after drug-eluting stent implantation (ARCTIC-Interruption): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1577–1585. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60612-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colombo A, Chieffo A, Frasheri A, et al. Second-generation drug-eluting stent implantation followed by 6-versus 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy: the SECURITY randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;64:2086–2097. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feres F, Costa RA, Abizaid A, et al. Three vs twelve months of dual antiplatelet therapy after zotarolimus-eluting stents: the OPTIMIZE randomized trial. Jama. 2013;310:2510–2522. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulz-Schupke S, Byrne RA, Ten Berg JM, et al. ISAR-SAFE: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 6 versus 12 months of clopidogrel therapy after drug-eluting stenting. European heart journal. 2015 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu523. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valgimigli M, Campo G, Monti M, et al. Short- versus long-term duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: a randomized multicenter trial. Circulation. 2012;125:2015–2026. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.071589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilard M, Barragan P, Noryani AA, et al. Six-month versus 24-month dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug eluting stents in patients non-resistant to aspirin: ITALIC, a randomized multicenter trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.11.008. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeh RW, Czarny MJ, Normand SL, et al. Evaluating the generalizability of a large streamlined cardiovascular trial: comparing hospitals and patients in the dual antiplatelet therapy study versus the national cardiovascular data registry. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2015;8:96–102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhatt DL, Flather MD, Hacke W, et al. Patients with prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the CHARISMA trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49:1982–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. Design and rationale for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Prior Heart Attack Using Ticagrelor Compared to Placebo on a Background of Aspirin-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 54 (PEGASUS-TIMI 54) trial. American heart journal. 2014;167:437–444 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.