Abstract

In 2005, the NIH Chronic GVHD Consensus Response Criteria Working Group recommended several measures to document serial evaluations of chronic GVHD organ involvement. Provisional definitions of complete response, partial response, and progression were proposed for each organ and for overall outcome. Based on publications over the last nine years, the 2014 Working Group has updated its recommendations for measures and interpretation of organ and overall responses. Major changes include elimination of several clinical parameters from the determination of response, updates to or addition of new organ scales to assess response, and the recognition that progression excludes minimal, clinically insignificant worsening that does not usually warrant a change in therapy. The response definitions have been revised to reflect these changes and are expected to enhance reliability and practical utility of these measures in clinical trials. Clarification is provided about response assessment after the addition of topical or organ-targeted treatment. Ancillary measures are strongly encouraged in clinical trials. Areas suggested for additional research include criteria to identify irreversible organ damage and validation of the modified response criteria, including in the pediatric population.

Keywords: Chronic graft-versus-host disease, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, response criteria, consensus, guidelines

BACKGROUND

Overall survival or survival to permanent resolution of chronic GVHD and discontinuation of systemic immunosuppression represent long-term clinical outcomes that are accepted as measures of meaningful benefit in chronic GVHD clinical trials,1–3 but these long-term outcomes are not suitable for early-phase studies. Qualitative assessments of chronic GVHD manifestations can guide clinical decisions but are not adequate for measuring outcomes in clinical trials. To accelerate development and approval of novel therapeutic agents in chronic GVHD, quantitative research tools are needed to measure short-term responses to treatment and to predict long-term clinical benefit.

The 2005 NIH recommendations proposed a broad set of assessment measures that were thought to be feasible in most academic settings and were based on group consensus with input from subspecialists.4 For this 2014 update, the reconvened Working Group reviewed the literature, and then used a consensus process to reconsider each prior recommendation while adding new recommendations. Table 1 summarizes the 2014 changes to the original 2005 recommendations. Measures are designated as “recommended” if available data support their use for response measurement (Table 2). Measures are designated as “strongly encouraged” if they were previously recommended but the interpretation of data or utility of measures remain controversial, “exploratory” if the Working Group believes that substantial additional research is warranted before adoption, and “no longer recommended for general chronic GVHD trials” if the measure was previously recommended, but data have demonstrated no utility or have not been generated since 2005 (Table 3).

Table 1.

2014 changes to the 2005 recommendations

| Organ Measures | 2005 Recommendation | 2014 Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | Skin response is measured using the body surface area of erythematous rash, moveable sclerosis and non-moveable sclerosis | Skin response is measured using the updated NIH Skin Score Detailed collection of type of BSA involvement no longer collected except for non-moveable sclerosis Skin and/or joint tightening is an exploratory measure |

| Size of skin ulcers is documented | Presence or absence, not size, of skin ulcer is documented | |

| Eye | Eye response is measured by change in Schirmer’s test | Eye response is measured by change in NIH Eye Score |

| Mouth | Mouth response is measured by change in the Modified Oral Mucosa Score. Scores range from 0–15 | Remove mucoceles from the Modified Oral Mucosa Score. Scores range from 0–12 |

| Oral chronic GVHD is described as “hyperkeratosis” changes | The term “hyperkeratosis” is replaced by “lichen-like” changes | |

| Patients’ symptoms of mouth dryness and mouth pain are captured on 0–10 scales | No longer recommended. Mouth sensitivity is still captured on a 0–10 scale. | |

| GI | Change from a 0 to 1 in the NIH GI and esophagus response measures are considered progression | Change from a 0 to 1 in these measures is no longer considered progression |

| Liver | Liver response is measured by change in ALT, bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase | Simplification of the definitions of improvement and progression |

| Lung | Lung response is measured by change in %FEV1 and DLCO after calculation of the Lung Function Score | Lung response is measured by change in %FEV1 |

| Joints and Fascia | Joints and Fascia are not included in response assessment | The NIH Joint and Fascia Score and the P-ROM are used to assess joint response |

| Hematology | Platelet count and absolute eosinophil count are collected to measure hematologic response | Platelet count and absolute eosinophil count are collected only at baseline to provide prognostic information |

| Other | All abnormalities are documented and attributed to chronic GVHD | All abnormalities are documented but the organ is not evaluable if there is another well documented non-chronic GVHD cause |

| Ancillary Measures | ||

| Quality of life | Pediatric surveys CHRI and ASK are recommended | No longer recommended |

| SF36, FACT-BMT and HAP are recommended | SF36 OR FACT-BMT plus HAP are strongly encouraged | |

| Functional status | Two minute walk distance is recommended | Two minute walk distance provides prognostic information, consider assessing only at baseline |

| Grip strength is recommended | No longer recommended | |

| Karnofsky or Lansky performance status is recommended | Karnofsky or Lansky performance status is strongly encouraged only at baseline | |

| Response Assignments | ||

| Response category | Mixed response category is not recognized | Mixed response category is recognized and considered progression |

| Other | No comment on whether responses can be assessed in the setting of additional organ-directed treatments | If topical or organ-directed treatments are added, any CR or PR in those organs should be reported as occurring in the setting of additional local therapy. |

| No comment on whether responses can be assessed in the setting of additional systemic immunosuppressive treatments | Addition of systemic immunosuppressive treatment is considered treatment failure, unless otherwise specified in the protocol |

Table 2.

2014 Recommended chronic GVHD-specific core measures for assessing responses in chronic GVHD trials

| Measure | Clinician Assessed | Patient Reported |

|---|---|---|

| Assessments | NIH Skin Score (0-3) | N/A |

| NIH Eye Score* (0-3) | ||

| Modified OMRS (0-12) | ||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL), ALT (U/L) | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | ||

| FEV-1 (Liters, % predicted) | ||

| NIH Joint Score (0-3) | ||

| Photographic range of motion (4-25) | ||

| Symptoms | NIH Lung Symptom Score (0-3) | Lee Symptom Scale 7 (0-100) |

| Upper GI Response Score (0-3) | Skin itching (0-10) | |

| Lower GI Response Score (0-3) | Mouth sensitivity (0-10) | |

| Esophagus Response Score (0-3) | Chief eye complaint (0-10) | |

| Global rating scales | None-Mild-moderate-severe 7 (0-3) | None-Mild-moderate-severe7 (0-3) |

| 0-10 severity scale 8 (0-10) | 0-10 severity scale 8 (0-10) | |

| 7 point change scale 9 (-3 to +3) | 7 point change scale 9 (-3 to +3) |

Components include both signs and symptoms

NIH, National Institutes of Health; OMRS, Oral Mucosa Rating Scale; FEV-1, forced expiratory volume, first second; ALT, alanine transaminase; GI, gastrointestinal;

Table 3.

Strongly encouraged, exploratory, and no longer recommended response measures for general chronic GVHD trials

| Organ* | Strongly Encouraged | Exploratory | No longer recommended for general chronic GVHD studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | Clinician and patient reported skin and/or joint tightening | Body surface area of erythematous changes and moveable sclerosis Pigmentary changes |

|

| Eyes | Schirmer’s test | ||

| Mouth | Mucoceles, patient-reported mouth pain and dryness on a 0–10 scale | ||

| Upper GI | Weight | ||

| Lower GI | Weight | ||

| Liver | Aspartate aminotransferase | ||

| Lungs | Corrected DLCO, FVC, TLC, RV | ||

| Hematologic | Platelet count, absolute eosinophil count | ||

| Genitals | Female and male self-reported question: “Worse genital discomfort” on a 0–10 scale | ||

| Ancillary measures | SF-36v.2 (0–100) or FACT-BMT (0–148) in adults HAP (if the SF-36v2 is not used) (0–94) Patient overall severity score 0–10 |

PedsQL Clinician and patient-reported severity (0–10) and change (−3 to +3) for organ-specific chronic GVHD manifestations |

Grip strength Children’s Health Rating Inventory Activity Scale for Kids |

No measures for esophagus or joints and fascia

SF-36v2, Medical Outcome Study Short Form 36, version 2; FACT-BMT, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplantation subscale; HAP, human activities profile; PedsQL, pediatric quality of life

PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT

This document summarizes proposed measures and criteria for use in clinical trials involving patients with chronic GVHD where the goal is to demonstrate improved patient outcomes or to obtain regulatory approval. The measures and criteria do not necessarily apply to routine patient care or to trials with limited resources or trials that target specific organs. The following general principles were applied in selecting the recommended measures:

The measures should be easy for all care providers to collect and should be attainable in the outpatient setting.

The criteria should be adaptable for use in adults and children.

The measures should focus on the most important and common manifestations of chronic GVHD and should not attempt to characterize all possible clinical manifestations.

Quantitative measures should be favored over qualitative measures.

Measurements of symptoms, global ratings, function, and quality of life should be made separately from each other, and scales with established psychometric characteristics and desirable measurement properties should be used whenever possible.5,6

The Working Group had three additional goals: a) to propose provisional definitions of complete response, partial response, and disease progression for each organ and for overall response; b) to suggest appropriate strategies for using response measures in therapeutic clinical trials; and c) to outline future research directions.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

“Chronic GVHD-specific” core measures are a) clinician-assessed and patient-reported signs and symptoms, b) the Lee Chronic GVHD Symptom Scale, and c) the clinician-assessed or patient-reported global rating scales (Table 2).7–9 Easily recorded continuous data should not be reduced to pre-specified categories.

“Chronic GVHD non-specific” ancillary measures for adults include either the SF-36 version 2 questionnaire10,11 or the FACT-BMT12 plus the Human Activity Profile (HAP) questionnaire13 (Table 3). These measures are strongly encouraged but remain optional and should not be used as primary endpoints in chronic GVHD trials.

Age-appropriate modifications of existing measures should be used in children with chronic GVHD.

Documenting response involves a comparison of chronic GVHD activity at two time points. Definitions of response are offered for each organ and for overall outcomes, although each protocol should define precisely how response will be determined. Simple forms that may be used for clinician and patient assessments are provided in Appendices A and B, and at http://www.asbmt.org/?page=MeasureCGVHD. Currently, objective and subjective data are kept separate. The field would benefit from methods that integrate physical exam and laboratory findings with clinician- and patient-reported information to determine accurately whether chronic GVHD is improving or worsening.

Measurements should be made at regular intervals, for example every three months, and whenever a new systemic immunosuppressive treatment is started or the patient stops study treatment. Efforts to document the durability of response are strongly encouraged.

-

Collaboration with sub-specialists is encouraged in order to develop and validate more detailed organ- or site-specific measures that could improve sensitivity to change or serve as primary endpoints in organ-specific therapy trials. For example:

Skin: skin-specific scoring systems,14 durometer,14–16 histopathology,15 or imaging (ultrasound, MRI)17,18

Eyes: corneal staining grading,19,20 conjunctival grading,21 Ocular Surface Disease Index22

Oral: Oral Health Impact Profile-14,23 saliva analysis24, Oral Mucosa Rating Scale25

Function: range of motion measured by goniometer, fatigue severity scale28–30

Measures that predict outcomes, but are not sensitive to change or do not directly measure chronic GVHD manifestations should be collected at baseline but not used in the response assessment, for example: performance status, platelet count, eosinophils, and the two-minute walk test.

PROPOSED MEASURES OF CHRONIC GVHD RESPONSE ASSESSMENTS

The Working Group identified two broad categories of tools for use in the assessment of response. These include a) the “Chronic GVHD-specific” core measures that directly measure organ-specific manifestations of chronic GVHD, and b) the “non-specific” ancillary measures that could reflect the overall impact of chronic GVHD, treatment, comorbidity, or other illness on function or quality of life.

CHRONIC GVHD-SPECIFIC CORE MEASURES

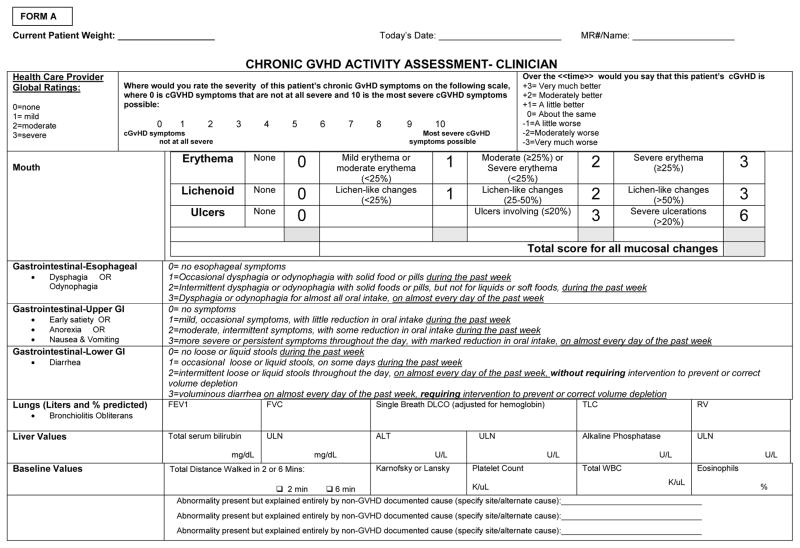

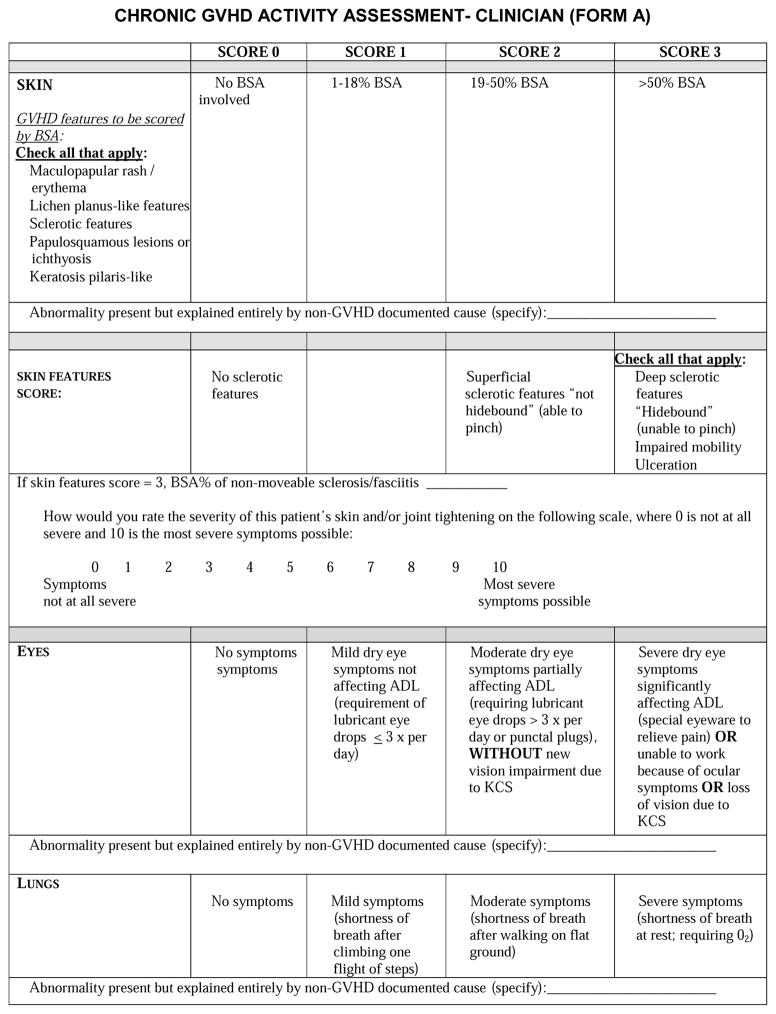

The core clinician-assessed and patient-reported chronic GVHD-specific measures are described in the following sections: organ-specific assessments, chronic GVHD symptoms, clinician- and patient-reported global ratings (Table 2, Form A, Form B). Specific pediatric considerations are highlighted where appropriate. For the assessment of symptoms in younger children, depending on the child’s development, assistance can be provided by the health care provider or the parent. The Working Group also recommends formal, interactive training for all assessors in order to minimize intra- and inter-observer variability.31–33 Whenever possible, the same clinician should score a patient serially to reduce measurement error due to inter-observer variability.

FORM A.

FORM B.

Organ-specific assessments

The discussion below is applicable to signs and symptoms potentially attributable to chronic GVHD. Other documented causes of the abnormality, such as infection, injury, or other non-GVHD cause, should be indicated on the case report forms, and if explained entirely by non-GVHD documented cause, the respective organ may not be evaluable for response assessment. The measures below reflect the minimum data documentation in chronic GVHD trials. Some studies will require more detailed organ assessments.

Skin and skin appendages

Skin is the most frequently affected organ in chronic GVHD, and manifestations are highly variable. In the 2005 response criteria, proposed measures included the percentage of body surface area (BSA) by the type of involvement (erythematous rash, movable sclerosis, non-moveable sclerosis). BSA measurement on a continuous scale suffered from poor inter-rater reliability, particularly for moveable sclerosis.32 Thus, the 2014 revision recommends the simpler NIH Skin Score instead, because it correlates with chronic GVHD severity, symptoms, and survival.34 The NIH Skin Score is a 0–3 score that summarizes BSA involvement into four categories: no skin involvement; ≤18% without sclerosis; 19–50% or any moveable sclerosis; and >50% or any non-movable sclerosis, impaired mobility, or ulcers. The “Rule of 9’s” as an estimate of BSA involvement is intended for use in adults and is less accurate in children, particularly young children. For the sake of simplicity, we recommend using the “Rule of 9’s” for all children, except for those less than one year of age. A body surface area grid for children less than 1 year of age can be found at http://www.asbmt.org/?page=MeasureCGVHD. BSA assessment should include superficial skin eruptions, moveable sclerosis and non-movable sclerosis. Superficial skin eruptions of cutaneous chronic GVHD include maculopapular, erythematous, lichen planus-like, papulosquamous, ichthyotic, and keratosis pilaris-like rashes. Superficial sclerosis (moveable) includes both lichen sclerosis-like and morphea-like lesions. Deep sclerosis (non-movable) includes diffuse, fixed (hidebound) sclerosis, fibrosis of subcutaneous fat septae (“rippling”) and fasciitis (“groove sign”). The presence of ulcers should be noted but documentation of the size is no longer required.

Sclerotic changes are common in skin GVHD, difficult to measure reliably, and respond slowly to therapy. Since quantitative methods to measure the depth of sclerotic involvement are not available in a general oncology practice, these changes have been described in more qualitative terms related to thickening, pliability, color, adherence to underlying tissues, or changes in joint mobility. No validated scale exists for assessing sclerotic skin changes of chronic GVHD. Measures such as the Rodnan scale for assessment of systemic sclerosis might be helpful for clinical evaluation, but this scale is not suitable for use in clinical trials because it does not address the full spectrum of sclerotic skin manifestations in chronic GVHD. There is an urgent need for the development of more quantifiable and reproducible measurements or imaging methods that could be used in patients with sclerotic skin manifestations of chronic GVHD.14–18 Pending development of these measures, the Working Group recommends recording the percentage of BSA involved with deep sclerosis/fasciitis and using an exploratory 0–10 semi-quantitative scale for capturing clinician-perceived severity of sclerosis using the descriptor “skin and/or joint tightening.”

Pigmentary changes do not indicate chronic GVHD disease activity per se. Moreover, changes in pigmentation occur gradually and are perceptible only across long time intervals. Thus, these changes are not scored for the purposes of response assessment.

Patient-reported measures of skin disease are also useful for measuring response. The skin subscale of the Lee Symptom Scale correlates with severity of skin disease, and changes in patient-reported skin symptoms correlate with survival.34 Patients should report their most severe itching during the past week, rated according to a 0 – 10 scale, since itching is the most frequent cutaneous symptom of chronic GVHD. These are considered recommended measures. A semi-quantitative exploratory measure, “Your skin and/or joint tightening at its worst,” on a 0–10 scale has been added to capture severity of skin sclerosis. Informal cognitive testing suggested that including both “skin” and “joint” tightening in the question was not confusing for patients.

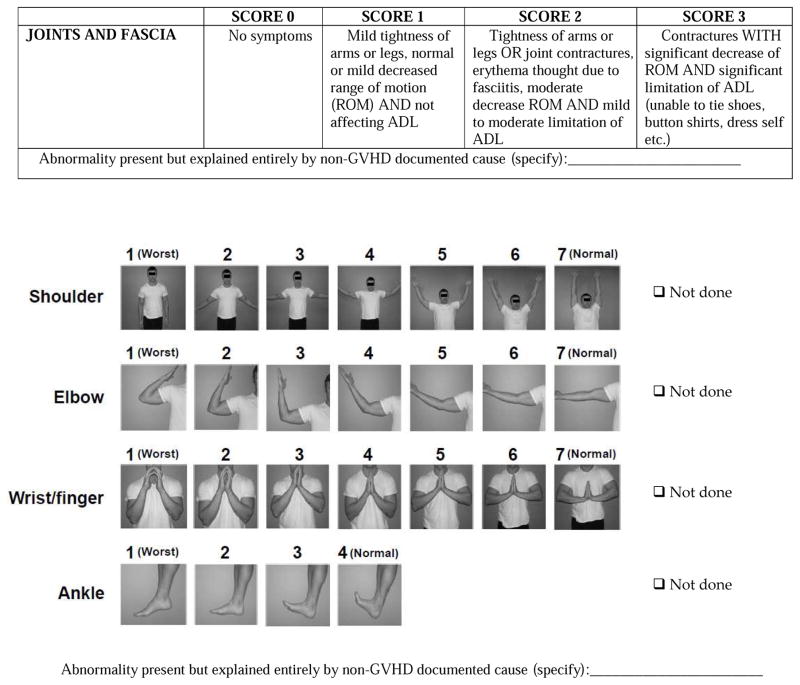

Musculoskeletal connective tissue

Assessment of joint range of motion is a very useful objective measure of chronic GVHD tissue response in patients with sclerotic changes involving large joints. The NIH Joint Score and the photographic range of motion (P-ROM) scales correlate with change in joint involvement, and are recommended measures.35

Eyes

Dry eyes represent either lacrimal gland dysfunction or destruction that may be permanent. Although the Schirmer’s test36 was recommended in the 2005 criteria, subsequent studies have not supported the validity of this test in ocular chronic GVHD monitoring, and it is no longer recommended as a response measure for general chronic GVHD clinical trials.37 The NIH Eye Score is a recommended measure, since it detects improvement or worsening in ocular chronic GVHD.37 Scoring from 0–3 is based on symptoms, need for eye drops, and use of therapeutic procedures or devices.

Patients should report a “chief eye complaint” rated according to a 0 –10 scale for peak severity during the past week. The complaint can change from visit to visit, but only one “chief eye complaint” is graded. This method is simple to use but may impose undesirable limitations in patients with multiple complaints. The eye subscale of the Lee Symptom Scale and the Ocular Surface Disease Index are also sensitive to change,37 but the Lee eye subscale is more convenient since it is shorter and is already included in the composite symptom battery.

Mouth

Previously, oral chronic GVHD was assessed using a NIH modification of the Schubert Oral Mucosa Rating Scale25 (OMRS) that scores oral surfaces from 0 – 15, with higher scores indicating more severe involvement. The four 2005 NIH Consensus chronic GVHD manifestations assessed in this scale included a) mucosal erythema (color intensity and percent of oral surface area); b) lichen-like hyperkeratosis (percent of oral surface area); c) ulcerations (percent of oral surface area); and d) mucoceles (total number). Subsequent studies have suggested that mucoceles are not reliably assessed,32,33,38 and their enumeration does not correlate with important clinical outcomes.38,39 Thus, the Working Group recommends removing mucoceles from the NIH-modified OMRS, resulting in a further modified 0–12 scale. The term “hyperkeratosis” has been removed and clarified as “lichen-like changes” instead.

Patients should report their mouth sensitivity (irritation resulting from normally tolerated spices, foods, liquids, or flavors), rated according to a 0 – 10 scale for peak severity during the past week. Children may have an easier time with a 0–3 scale, but this format has not been validated and may be less sensitive to change. Evaluation of mouth dryness and mouth pain on 0–10 scales is no longer recommended for general chronic GVHD trials.40 Mouth symptoms are also captured in the Lee Symptom Scale, as part of a recommended battery.

Hematopoietic

Parameters to be documented at trial enrollment include platelet count41 and absolute eosinophil count,42,43 since they may have prognostic significance. These measures are not part of the response assessment, and their ongoing documentation is no longer recommended.

GI tract

Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are difficult to measure quantitatively. GI symptoms during the preceding week are graded through interview by the examining clinician according to 0 – 3 severity scales for the upper and lower GI tract and esophagus. Patients with chronic GVHD often have weight loss that is not explained by GI symptoms.44 Although the exact relationship between weight loss and chronic GVHD activity is not clear, recording patient weight at each scheduled evaluation is strongly encouraged, given the simplicity of this measure and its potential importance for monitoring the success of therapy.

Liver

Liver injury should be assessed according to the most recent laboratory results for total serum bilirubin (mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase (U/L) and alanine aminotransferase (U/L). Laboratory upper limits of normal should also be recorded. Aspartate aminotransferase is not recorded since it is not specific for liver inflammation.

Lung

The 2005 response criteria recommended the lung function score (LFS), based on percent predicted forced expiratory volume in the first second (%FEV1) and single breath diffusion lung capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) adjusted for hemoglobin, because it is predictive of respiratory failure and mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.45,46 Experience in patients with steroid-refractory GVHD has suggested that the LFS is sensitive to change and is useful as a response measure.47 On the other hand, DLCO is not directly affected by bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) did not perform as well as the NIH Lung Symptom Score in predicting non-relapse mortality and survival in an observational study, although conclusions were limited by 50% missing PFT data.48 PFTs cannot be performed in children younger than 5 years of age, and DLCO usually cannot be measured in children younger than 10 years. FEV1 may not be reliable in children.49 Another therapeutic study that included mostly BOS patients showed that a decrease in %FEV1 or FVC of greater than 10% was highly correlated with an increased risk of death within 5-years.50

The Working Group recommends recording the %FEV1, FEV1 (L), and forced vital capacity (FVC), and strongly encourages parallel documentation of DLCO corrected for hemoglobin, total lung capacity (TLC), and residual volume (RV) to allow further validation studies, including exploration of restrictive lung disease as a manifestation of chronic GVHD.51–53 If available, the %FEV1 value should be prioritized for response assessment. However, if PFTs are not available, the NIH 0–3 Lung Symptom Score may be used for response assessment. Of note, airway hyper-responsiveness in, and variable cooperation by, pediatric patients may require repeated PFTs in cases where abnormal values are observed. %FEV1 may decline due to respiratory infections or progressive restrictive physiology due to extrinsic thoracic compression from sclerosis or respiratory muscle weakness, and these causes should be considered if PFTs worsen. Exploration of the %FEV1 slope as an outcome measure to account for the change in disease trajectory is encouraged.54,55 Chronic GVHD of the lung is not a bronchodilator-responsive process, so bronchodilators are not required to assess response for general chronic GVHD trials. Patients with reactive airways disease such as asthma, who have a documented bronchodilator response, should continue to receive bronchodilators during PFTs.

Genitals

Women should be asked specific questions relating to vulvar and vaginal symptoms, such as burning, pain, discomfort, or dyspareunia. Patients who report problems should be referred to a gynecologist experienced in the care of patients with chronic GVHD. Since such symptoms could be under-reported or caused by conditions other than chronic GVHD,56 and because proper evaluation requires a specialist exam, measures of genital response are considered exploratory. Both female and male genital symptoms may be captured by the exploratory item rating “Worst genital discomfort” on a scale from 0–10 in adolescent and adult patients while this item will not work in pediatric patients. Academic gynecologists interested in chronic GVHD are developing precise vulvo-vaginal assessment scales. These scales will be useful in selected trials where vulvar and vaginal changes are the primary endpoints of interest.26,27

Other organ systems may be affected by chronic GVHD, but are either uncommon or difficult to quantify by non-specialists. The Working Group encourages investigators to develop and validate response assessment tools that could detect meaningful clinical benefit in trials focused on specific organs or manifestations.

Chronic GVHD symptoms

Lee and colleagues developed a symptom scale designed for individuals with chronic GVHD.7 The questionnaire asks patients to indicate the degree of bother that they experienced during the past four weeks due to symptoms in seven domains potentially affected by chronic GVHD (skin, eyes and mouth, breathing, eating and digestion, muscles and joints, energy, emotional distress). Published evidence supports its validity, reliability, and sensitivity to chronic GVHD severity.34,37,48,57,58 The symptom scale can be completed in approximately 5 minutes. The reporting time frame may be decreased to one week to specifically capture more recent symptoms.

The Lee Symptom Scale has been tested only in patients older than 18 years of age. Given its face validity and other desirable properties, however, this scale could be used for assessment of chronic GVHD in pediatric patients using either child or parent report, after appropriate modification and psychometric evaluation.59 Information may be obtained by self-report from adolescents over 12 years of age. For children who are 8–12 years of age, data should be obtained with the assistance of parents and the health care provider. Investigators are working on developing a symptom scale appropriate for all pediatric patients.60

The Lee Scale measures symptom bother as distinguished from symptom intensity, which is reported on the forms in Appendix B.61 The degree to which patients report that they are bothered by a symptom represents a global assessment incorporating not only the intensity of the symptom and its frequency, but also the degree to which it causes emotional disturbance or interferes with functioning. For example, oral sensitivity may be severe, but patients may report that they are not bothered or distressed by this symptom. By contrast, skin itching may not be very intense or frequent but may cause great distress. Additional study is needed to determine the relationships between symptom intensity, frequency, and distress or bother in patients with chronic GVHD and the degree to which these are distinct dimensions of the symptom experience.

Clinician-assessed and patient-reported global rating scales

Clinician perceptions

Physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants should provide a subjective assessment of current overall chronic GVHD severity on a 4-point scale (no chronic GVHD, mild, moderate, severe)7 without knowledge of the calculated NIH global severity score. They should also provide an assessment of current overall chronic GVHD severity on an 11-point numerical scale (0 indicates no GVHD manifestations; 10 indicates most severe chronic GVHD symptoms possible).62 The categories of mild, moderate, and severe have been used in previous studies for patient and clinician assessment, where they were often undefined but showed good prognostic ability.7,63 Clinicians should also provide their evaluations of chronic GVHD changes since the last assessment scored on a 7-point scale (very much better, moderately better, a little better, about the same, a little worse, moderately worse, very much worse).9 These semi-quantitative assessments may detect qualitative improvements that are clinically meaningful but not well captured using other measures.64 The protocol and case report form should specify the time interval for assessing changes.

Patient perceptions

Similarly, at each assessment, patients should score their perceptions of overall chronic GVHD severity, overall severity of symptoms, and change in symptom severity compared with the last assessment, using the same response options used by clinicians.

The exact role of global scales in chronic GVHD response assessments and their appropriate use as outcome measures in clinical trials remain to be determined. These scales could be sensitive to qualitative changes that might otherwise escape detection if the assessments were limited to quantitative measures. They are used in studies that establish clinically meaningful differences in measures. A potential limitation is that personality traits can influence patient perceptions or self-report.65

CHRONIC GVHD NON-SPECIFIC ANCILLARY MEASURES

Non-specific measures of function and patient-reported outcomes related to functional status and health-related quality of life could potentially offer additive objective and subjective data regarding the effects of chronic GVHD and its therapy. The GVHD non-specific measures listed in Table 3 assess different dimensions of the patient experience. These measures are strongly encouraged to allow investigation of the potential role of these non-specific measures as response measurements in chronic GVHD therapeutic clinical trials.

Functional status

For an extremely complex, multi-system disease such as chronic GVHD, objective measures of physical performance and patient-reported measures of functional status could represent important surrogate outcomes that might be more informative than the measures described above for assessing response in some situations (e.g., advanced skin sclerosis). At the very least, measures of functional status can provide corroborative evidence of important changes after therapy. In other patient populations with chronic diseases,66–68 such outcomes have been extensively applied, and population norms for both physical performance measures and self-reported functional status are available. Since the use of functional endpoints in chronic GVHD assessment has not been extensively tested, and since these measures do not directly assess chronic GVHD manifestations, functional status outcomes can be used only as optional secondary endpoints in chronic GVHD trials until further information is available.

An objective measure of physical performance is the 2-minute walk distance (total distance in feet walked in 2 minutes)69,70,71 measured at baseline as a prognostic factor since it correlates with survival,72 but not as a response measure at follow-up. Although measurement properties have been less thoroughly examined for the 2-minute walk distance than those for the 6-minute walk distance in other chronic diseases, the 2-minute walk distance could suffer from a ceiling effect in patients without impaired physical functioning. The 6-minute walk distance is often used as an endpoint in non-HCT lung treatment trials.73 Additional evaluation is needed to determine whether the 6-minute walk distance is superior in unimpaired patients. Age-matched norms for 2-minute walk distance are available for adults while age-matched norms are available for the 6-minute walk test for children and adolescents.74–76 Of note, no data are currently available to support the use of the 2-minute walk distance in pediatric HCT patients. Grip strength77–79 measured using a hydraulic dynamometer to capture muscle strength of the upper extremity80 is no longer recommended, as it does not correlate with chronic GVHD severity or outcome.72

Human Activity Profile

The strongly encouraged patient-reported measure of physical activity in adults is the Human Activity Profile (HAP) questionnaire. The 94 questions are presented in ascending order according to the metabolic equivalents of oxygen consumption required to perform each activity.13 The HAP therefore provides a survey of activities that the patient performs independently across a wide range of metabolic demand, beginning with getting out of bed, bathing, dressing, performing a series of progressively more physically demanding household chores, and ending with running or jogging 3 miles in 30 minutes or less. While the HAP correlates with chronic GVHD severity,72,81 it may not be necessary if the SF-36 is collected, since the SF-36 also assesses physical activity. The Working Group no longer recommends the Activities Scale for Kids (ASK)82–84 due to lack of data in patients with chronic GVHD.

Performance scales

The Karnofsky or Lansky Performance Scale is commonly used in clinical assessments of chronic GVHD and has prognostic value for survival, so it is strongly encouraged at enrollment.85,86 These scales are not valid measures of response.

Health-Related Quality of Life

The effects of chronic GVHD and its treatment on general physical and emotional health and health-related quality of life are other endpoints that may be responsive to change as a result of chronic GVHD therapy.87 Since evidence of sensitivity to change is lacking, these instruments are only “strongly encouraged.” The SF-36v2 (Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36-item Questionnaire version 2) has had wide application and is well accepted as a measure of self-reported general health and the degree to which health impairments interfere with activities of daily living and role function.11,88 The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) is a suite of health-related quality of life instruments that have well-developed psychometric properties, have been used widely in oncology, and have available population norms for those with both mild and severe chronic illnesses, as well as for cancer patients and survivors. The core measure (FACT-G) is combined with an additional 12-item disease-specific module that evaluates concerns common to patients who have had hematopoietic cell transplantation, and the entire instrument is called the FACT-BMT.12 The SF-36v2 (36 items) and FACT-BMT (47 items) instruments are appropriate for adults, however they evaluate similar constructs and in order to minimize burden for respondents, only one should be used. The SF-36v2 may be used alone. If the FACT-BMT is used, it should be combined with the HAP to capture functional abilities. The NIH PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) measures have not been studied in chronic GVHD, but their evaluation is encouraged.89 Previously recommended pediatric scales, the Child Health Ratings Inventories (CHRIs) generic core and Disease-Specific Impairment Inventory-HSCT,90–92 are no longer recommended due to lack of data in chronic GVHD. Instead, the Working Group recommends exploration of the PedsQL based on results in other chronic illnesses and hematopoietic cell transplantation.93–95

Cross-sectional studies have shown that chronic GVHD has an adverse effect on quality of life,96 but the role of quality of life as a measure of response to therapy or as a predictor of long-term outcome remains to be defined. Patient-reported quality-of-life measures can augment, but cannot replace, quantitative measures of chronic GVHD activity in clinical trials. Since responses to patient surveys may be affected by personality traits65 and baseline status, cross-sectional measurements may not be interpretable.

CHRONIC GVHD DATA COLLECTION FORMS

Appendices A and B at http://www.asbmt.org/?page=MeasureCGVHD (Forms A and B) provide downloadable data collection forms for the recommended clinician-assessed and non-copyrighted patient-reported measures. It is not necessary to include all recommended or strongly encouraged measures in every trial, and judgment must be used in deciding which items will best suit the needs of each study. Organ-specific trials will likely add more detailed measures, perhaps requiring subspecialist evaluations. In all studies, the measures to be collected and the timing of the assessments must be specified.

PROVISIONAL CRITERIA FOR DEFINITION OF RESPONSE

In order to assess response, disease manifestations at two pre-defined time points must be compared, and a judgment must be made as to whether the magnitude of any change qualifies as improvement or deterioration. This magnitude of change should reflect genuine clinical change, and the criteria should be clarified and standardized as much as possible to avoid measurement error. This standardization may be relatively easy to establish for manifestations that can be measured quantitatively with little day-to-day variation but will be more difficult to establish for manifestations that can be measured only in more qualitative ways. The Working Group proposes the following consensus definitions for assessment of overall response and for measurable organ response (Table 4).

Table 4.

Response determination for chronic GVHD clinical trials based on clinician assessments

| Organ | Complete Response | Partial Response | Progression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | NIH Skin Score 0 after previous involvement | Decrease in NIH Skin Score by 1 or more points | Increase in NIH Skin Score by 1 or more points, except 0 to 1 |

| Eyes | NIH Eye Score 0 after previous involvement | Decrease in NIH Eye Score by 1 or more points | Increase in NIH Eye Score by 1 or more points, except 0 to 1 |

| Mouth | NIH Modified Oral Mucosa Rating Score 0 after previous involvement | Decrease in NIH Modified Oral Mucosa Rating Score of 2 or more points | Increase in NIH Modified Oral Mucosa Rating Score of 2 or more points |

| Esophagus | NIH Esophagus Score 0 after previous involvement | Decrease in NIH Esophagus Score by 1 or more points | Increase in NIH Esophagus Score by 1 or more points, except 0 to 1 |

| Upper GI | NIH Upper GI Score 0 after previous involvement | Decrease in NIH Upper GI Score by 1 or more points | Increase in NIH Upper GI Score by 1 or more points, except 0 to 1 |

| Lower GI | NIH Lower GI Score 0 after previous involvement | Decrease in NIH Lower GI Score by 1 or more points | Increase in NIH Lower GI Score by 1 or more points, except from 0 to 1 |

| Liver | Normal ALT, alkaline phosphatase, and Total bilirubin after previous elevation of one or more | Decrease by 50% | Increase by 2x ULN |

| Lungs | -Normal %FEV1 after previous involvement -If PFTs not available, NIH Lung Symptom Score 0 after previous involvement |

-Increase by 10% predicted absolute value of %FEV1 -If PFTs not available, decrease in NIH Lung Symptom Score by 1 or more points |

-Decrease by 10% predicted absolute value of %FEV1 -If PFTs not available, increase in NIH Lung Symptom Score by 1 or more points, except 0 to 1 |

| Joints and Fascia | Both NIH Joint and Fascia Score 0 and P-ROM score 25 after previous involvement by at least one measure | Decrease in NIH Joint and Fascia Score by 1 or more points or increase in P-ROM score by 1 point for any site | Increase in NIH Joint and Fascia Score by 1 or more points or decrease in P-ROM score by 1 point for any site |

| Global | Clinician overall severity score 0 | Clinician overall severity score decreases by 2 or more points on a 0–10 scale | Clinician overall severity score increases by 2 or more points on a 0–10 scale |

Objective measures of GVHD activity

Overall response

Three general categories of overall response are proposed for interpretation of clinical trials: complete response, partial response, and lack of response (unchanged, mixed response, progression). Complete response is defined as resolution of all manifestations in each organ or site, and partial response is defined as improvement in at least one organ or site without progression in any other organ or site as described in the following sections on organ response. The Working Group recommends that skin, mouth, liver, upper and lower GI, esophagus, lung, eye, and joint/fascia be considered in evaluating overall response. Genital tract and other manifestations are not included due to lack of validated response measures.

Complete organ response

The term “complete organ response” indicates resolution of all manifestations related to chronic GVHD in a specific organ. This category may not apply to organs with irreversible damage. The Working Group extensively discussed whether a “near CR” category was justified to indicate resolution of all reversible organ manifestations despite residual minor abnormalities. However, no consensus could be reached on the definition of “irreversibility,” and there is no evidence yet that the ultimate outcome after CR, near CR or PR differs. For these reasons, no “near CR” category is included, and both CR and PR are considered to be meaningful responses in clinical trials.

Partial organ response

The proposed definition of partial response in a specific organ requires an improvement in score from baseline that reflects genuine clinical benefit and exceeds the measurement error of the assessment tool: an improvement of 1 or more points on a 4–7 point scale, or an improvement of 2 or more points on a 10–12 point scale. Partial response in the liver requires at least a 50% improvement in ALT, alkaline phosphatase or total bilirubin. For patients with BOS, an absolute improvement in %FEV1 of 10% predicted or more (e.g., 50% to 60%) is considered a partial response50 as long as the initial %FEV1 is <70%. Normalization (>80%) is considered a complete response.

Because the NIH 0–3 Skin Score is now recommended for response assessment, even substantial improvement in sclerotic features will not be considered responses unless the NIH Skin Score improves. To aid in future measure development and validation, recording the body surface area involved with non-moveable sclerosis and collecting the severity of sclerosis on a semi-quantitative 0–10 scale is strongly encouraged. Trials targeting sclerotic chronic GVHD should use more detailed measures to document change in extent and functional consequences of sclerosis.

Organ Progression

Criteria for progression in each organ must be defined, since the overall category of partial response requires the absence of progression in any organ. For skin, eye, esophagus and upper and lower GI tract, a worsening of 1 point or more on the 0–3 scale is considered progression, except a change from 0 to 1, which is considered trivial progression since it often reflects mild, non-specific, intermittent, self-limited symptoms and signs that do not warrant a change of therapy. One study showed poor test-retest reliability in 0 to 1 GI changes, suggesting these minimal changes are also not reliably measured.97 For joint/fascia, a worsening of 1 point or more on the 0–3 scale is considered progression, even if from 0 to 1, because a change to score 1 was considered meaningful progression that would prompt a change in therapy. For joints assessed by the P-ROM, a worsening of 1 or more points for the 7 point scales and 1 or more points for the 4 point scale is considered progression. For mouth, a worsening of 2 or more points on the 12 point scale indicates progression. Worsening of liver GVHD is defined by an increase of 2 or more times the ULN for the assay for ALT, alkaline phosphatase or total bilirubin. For patients with lung involvement, absolute worsening of FEV1 by 10% predicted or more (e.g., 50% to 40%) is considered progression, as long as the final %FEV1 is <65% (since initial %FEV1 must be <75% to establish the diagnosis of lung involvement). If PFTs are not available, then worsening of the clinical lung score based on symptoms by 1 or more points should be scored as progression, except from score 0 to 1, which is considered trivial progression due to its lack of specificity for lung chronic GVHD. If the clinical lung symptom score worsens from 0 to 1, PFTs are encouraged if lung chronic GVHD is suspected.

For all organs, progression cannot be scored for manifestations with baseline values that are too close to the worst score, especially the organs using 0–3 scales, raising the possibility that patients could experience significant clinical worsening in an organ and still be considered a PR if they have measurable improvement in another organ. However, this concern is mitigated because many clinicians would change therapy in such a situation, and any addition of a new systemic immunosuppressive treatment is considered as indicating a lack of response.

Mixed Response

Mixed response is a new category defined as complete or partial response in at least one organ accompanied by progression in another organ. This category should be considered progression for the purposes of analysis but may aid in identifying organ-specific response patterns.

Unchanged

Outcomes that do not meet the criteria for complete response, partial response, progression or mixed response are considered unchanged. These outcomes will generally be considered non-responders unless specified otherwise by the protocol.

Limitations in measurement of organ responses

The response criteria do not account for qualitative changes. Clinical experience indicates that clinically important qualitative improvement often occurs before improvement in the objective measures. For this reason, the response criteria are not intended for use as the primary guide for clinical decisions. Certain organs or rare manifestations are not considered in the response criteria because quantitative assessments are not feasible, but these may be the most important manifestations of chronic GVHD for individual patients. To capture qualitative and global changes of the entire chronic GVHD syndrome, use of the clinician and patient assessed 0–10 global scale is strongly encouraged. The response criteria also do not account for the prior trajectory of abnormalities. For example, “stable” or “unchanged” disease might be considered a meaningful response when the prior trajectory was clear progression, as indicated, for example, by serial pulmonary function tests or rapidly progressive sclerosis, whereas “stable disease” after prior improvement or stability should not be considered a “response.” If the prior trajectory is important for response determination, the protocol should specify data to be documented in order to establish the trajectory.

Validation of response criteria

One study showed significant prognostic value of the NIH calculated responses for predicting survival in the context of a therapeutic trial47 but this conclusion was not supported by results from a large observational study.98 The criteria proposed in these guidelines have been modified based on publications since 2005 but still need to be validated prospectively for patients with chronic GVHD. For these reasons, the updated criteria are still provisional and subject to change with further clinical experience. Also, depending on the stringency of response definitions required by the specific study, these general guidelines could be modified to fit the needs of a particular protocol. Since the criteria are subject to change, we strongly recommend that case report forms should always record the actual numerical values for any measurement in order to allow future recategorization.

Caveats for assessment of response in clinical trials

Protocols must specify the times when response will be assessed, generally 2–6 months after enrollment, and the requirement(s) for durability of response. Permanent discontinuation of systemic chronic GVHD therapy confirmed for the duration of the observation period indicates a durable response. In principle, if additional systemic therapy for chronic GVHD is added before the end of the specified study period, the outcome is categorized as lack of response. The protocol should specify whether dose changes, for example increased steroid doses, are considered “additional systemic therapy.” Specific reasons for additional systemic therapy should be collected, since new treatments are sometimes added even though chronic GVHD is stable or improving (e.g., loss or change of insurance coverage, transportation or logistical issues, loss of central IV access etc.), and protocols should specify whether these cases should be categorized as lack of response.

Occasionally patients have co-morbid conditions that may interfere with response assessment (for example, a viral infection at the time of a planned PFT, temporary cholestasis due to a gallstone) or pre-existing irreversible conditions (for example post traumatic joint contracture, lung disease etc). In these situations the abnormality should still be scored but the check box (From A) should also indicate that the abnormality is explained entirely by a non-GVHD documented cause and the cause should be specified. Protocols should specify whether response measures may be delayed to allow resolution of a non-GVHD issue before response assessment or whether an organ entirely explained by another non-GVHD cause should be excluded for organ-specific or overall response assessment.

Addition of topical or organ-directed treatments generally make it impossible to be sure any response is due to systemic immunosuppressive treatment. Thus, topical and local therapy added after study enrollment must be documented in all patients and considered especially in patients who have a complete or partial response. Sensitivity analyses may be appropriate to determine whether exclusion of responses in the affected organs or sites changes the study conclusions. Some topical or organ-directed therapies may result in systemic effects due to absorption (e.g., oral, GI tract, lung, skin) or effects beyond the target organ (e.g., montelukast), and protocols should specify whether such treatments are allowed during the course of the trial or would automatically indicate a lack of response.

Patient-reported measures of GVHD activity

While improvement in patient functioning and symptoms is recognized as a measure of clinical benefit, the Working Group recommends that such outcomes be tabulated separately from clinician-assessed responses. The terms “complete response,” “partial response,” and “progression” do not technically apply to patient-reported or functional measures data. Patient-reported outcomes should be classified into response (clinically meaningful improvement) versus no response (no improvement or worsening), as measured by change between baseline and follow-up scores. The definition of improvement or worsening for such scales is based on the reliability of the measure (the variability due to measurement error) and is anchored against clinically perceptible changes. For global ratings and categorical scales, a 1-point change on a 0–3 or 1–7 point scale, or a 2-point change (0.5 standard deviation change) on a 0 – 10-point scale could be considered clinically meaningful.

Unless otherwise specified, for all patient-reported measures, a change of 0.5 standard deviation may be considered clinically meaningful for normally distributed data.99,100 For example, a distribution-based analysis was used to define improvement as a change of 6 – 7 points (0.5 SD) on the total chronic GVHD symptom score.7 For the physical and mental component summary scores for the SF-36, a change of 5 points is considered clinically meaningful.101,102 For HAP, clinically meaningful improvement is defined as a 10-point increase in the maximum activity score, since a change of this magnitude is sufficient to change the disability category at the middle of the scale.

An area for future investigation is to determine methods to integrate objective and subjective measures into holistic assessments of chronic GVHD disease activity. This approach has been used successfully in other autoimmune diseases. Examples include the American College of Rheumatology criteria for rheumatoid arthritis,103,104 Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI),105,106 ankylosing spondylitis short-term improvement criteria,107 the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K),108–111 Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Responder Index,112 and the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG).113,114

USE OF RESPONSE ASSESSMENT AS A PRIMARY ENDPOINT IN CLINICAL TRIALS

Use of the recommended measures and methods of calculating response has at least two important advantages. First, the field will gain valuable experience with the measures to help validate them in the context of therapeutic clinical trials. Second, the use of standardized assessment methods will allow comparison of efficacy between agents. At the same time, it will be possible to recalculate response categories if new information becomes available. Valid methods are urgently needed to document whether chronic GVHD is responding adequately.

More sophisticated assessments of certain organs such as skin, eyes, mouth, female genital tract, and joints may be needed for certain studies.14–19,21,22,25,26,115 Specialized expertise will be needed for these assessments, and efforts to define the criteria for measurement of response in these situations exceed the scope of the current proposal. The Working Group encourages development and validation of more precise assessment tools that could be used in organ-specific trials. In situations where expert assessors are not readily available, objective assessments of the skin, mouth, eye and external genitalia might be enhanced through review of serial photographs by a panel of expert individuals as blinded assessors who have no other information about the patient, so as to avoid bias and minimize potential inter-rater differences.33

Note that this document addresses only the measurement of clinical responses. It does not address other suggested surrogate endpoints such as failure-free survival, defined as absence of relapse, death and addition of new treatment,116,117 survival free of impairment, or reduction in steroid dosing that do not rely on direct assessment of organ responses.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The proposed response criteria are expected to enhance uniformity and feasibility of data collection methods and further advance standards of chronic GVHD clinical trials. Although this 2014 proposal is based on substantial interim evidence of utility and suggested clinical benefit for many proposed measures, these recommendations need to be tested further in prospective chronic GVHD therapy trials. Algorithms for measuring combinations of organ-specific and global responses to assess overall therapy response, and definition of minimal clinically meaningful cut off points may help in the development of highly relevant chronic GVHD response measurement tools, as demonstrated for other systemic inflammatory diseases. Improved methods will be needed to distinguish chronic GVHD disease activity from irreversible damage, leading toward development of a chronic GVHD activity index for clinical trials. The development and validation of laboratory biomarkers that reflect chronic GVHD activity could enhance methods based on clinical assessment.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, Intramural Research Program and Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program; Office of Rare Disease Research, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; Division of Allergy, Immunology and Transplantation, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease; National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Division of Blood Diseases and Resources. The authors want to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations that, by their participation, made this project possible: American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Center for International Bone and Marrow Transplant Research, US Chronic GVHD Consortium (supported by ORD and NCI), German-Austrian-Swiss GVHD Consortium, National Marrow Donor Program, the Health Resources and Services Administration, Division of Transplantation, US Department of Human Health and Services, Canadian Blood and Marrow Transplant Group, European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium, and the representatives of the Brazilian Chronic GVHD consortium (Drs. Maria Claudia Moreira, Marcia and Vaneuza Funke) and Deutsche José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung. The organizers are in debt to patients and patient and research advocacy groups, who made this process much more meaningful by their engagement. Acknowledgement goes to the Meredith Cowden GVHD foundation for facilitating the initial planning meeting in Cleveland in November of 2013 in conjunction with the National GVHD Symposium. The project group also recognizes the contributions of numerous colleagues in the field of blood and marrow transplantation in the US and internationally, medical specialists and consultants, the pharmaceutical industry, and the NIH and US Food and Drug Administration professional staff for their intellectual input, dedication, and enthusiasm on the road to completion of these documents. For their expert contributions to this 2014 NIH Consensus Response Criteria Working Group document special acknowledgements go to Drs. Edward Cowen, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Nathaniel Treister, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Kirsten Williams, NIH and DC Children’s National Medical Center, Pamela Stratton, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, Tina Dietrich-Ntoukas, University of Regensburg, George McDonald and Mark Schubert, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Carol Bassim, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, NIH, Janine Clayton, National Eye Institute, NIH, Gerhardt Hildebrandt, Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, Sharon Elad, University of Rochester, New York, Andrea Bacigalupo, University of Genoa, and Francis Ayuk, Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf. Project participants also recognize Drs. Joseph Antin and Gerard Socie for their independent expert reviews and comments on final documents at the June 2014 meeting.

APPENDIX: NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH CONSENSUS-DEVELOPMENT PROJECT ON CRITERIA FOR CLINICAL TRIALS IN CHRONIC GVHD STEERING COMMITTEE

Members of this committee included: Steven Pavletic, Georgia Vogelsang and Stephanie Lee (project chairs), Mary Flowers and Madan Jagasia (Diagnosis and Staging), David Kleiner and Howard Shulman (Histopathology), Kirk Schultz and Sophie Paczesny (Biomarkers), Stephanie Lee and Steven Pavletic (Response Criteria), Dan Couriel and Paul Carpenter (Ancillary and Supportive Care), Paul Martin and Corey Cutler (Design of Clinical Trials), Kenneth Cooke and David Miklos (Chronic GVHD Biology), Roy Wu, William Merritt, Linda Griffith, Nancy DiFronzo, Myra Jacobs, Susan Stewart, Meredith Cowden (members).

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the NIH, FDA or the United States Government.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stewart BL, Storer B, Storek J, et al. Duration of immunosuppressive treatment for chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2004 Dec 1;104(12):3501–3506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavletic SZ, Carter SL, Kernan NA, et al. Influence of T-cell depletion on chronic graft-versus-host disease: results of a multicenter randomized trial in unrelated marrow donor transplantation. Blood. 2005 Nov 1;106(9):3308–3313. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koc S, Leisenring W, Flowers ME, et al. Therapy for chronic graft-versus-host disease: a randomized trial comparing cyclosporine plus prednisone versus prednisone alone. Blood. 2002 Jul 1;100(1):48–51. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pavletic SZ, Martin P, Lee SJ, et al. Measuring Therapeutic Response in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: IV. Response Criteria Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006 Mar;12(3):252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acquadro C, Berzon R, Dubois D, et al. Incorporating the patient’s perspective into drug development and communication: an ad hoc task force report of the Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Harmonization Group meeting at the Food and Drug Administration, February 16, 2001. Value Health. 2003 Sep-Oct;6(5):522–531. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2003.65309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Revicki DA, Osoba D, Fairclough D, et al. Recommendations on health-related quality of life research to support labeling and promotional claims in the United States. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(8):887–900. doi: 10.1023/a:1008996223999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, Cook EF, Soiffer R, Antin JH. Development and validation of a scale to measure symptoms of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8(8):444–452. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12234170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000 Oct 1;89(7):1634–1646. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1634::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998 Jan;16(1):139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992 Jun;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE., Jr SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000 Dec 15;25(24):3130–3139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Cella DF, et al. Quality of life measurement in bone marrow transplantation: development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT) scale. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19(4):357–368. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daughton DM, Fix AJ, Kass I, Bell CW, Patil KD. Maximum oxygen consumption and the ADAPT quality-of-life scale. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1982 Dec;63(12):620–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seyger MM, van den Hoogen FH, de Boo T, de Jong EM. Reliability of two methods to assess morphea: skin scoring and the use of a durometer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997 Nov;37(5 Pt 1):793–796. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aghassi D, Monoson T, Braverman I. Reproducible measurements to quantify cutaneous involvement in scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 1995 Oct;131(10):1160–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falanga V, Bucalo B. Use of a durometer to assess skin hardness. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993 Jul;29(1):47–51. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70150-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottlober P, Leiter U, Friedrich W, et al. Chronic cutaneous sclerodermoid graft-versus-host disease: evaluation by 20-MHz sonography. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003 Jul;17(4):402–407. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumford K, Anderson JC. CT and MRI findings in sclerodermatous chronic graft vs. host disease. Clin Imaging. 2001 Mar-Apr;25(2):138–140. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(01)00240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bron AJ, Evans VE, Smith JA. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea. 2003 Oct;22(7):640–650. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200310000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogawa Y, Kim SK, Dana R, et al. International Chronic Ocular Graft-vs-Host-Disease (GVHD) Consensus Group: proposed diagnostic criteria for chronic GVHD (Part I) Scientific reports. 2013;3:3419. doi: 10.1038/srep03419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson MR, Lee SS, Rubin BI, et al. Topical corticosteroid therapy for cicatricial conjunctivitis associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004 May;33(10):1031–1035. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD, Reis BL. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000 May;118(5):615–621. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slade GD. Assessing change in quality of life using the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology. 1998 Feb;26(1):52–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb02084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imanguli MM, Atkinson JC, Mitchell SA, et al. Salivary gland involvement in chronic graft-versus-host disease: prevalence, clinical significance, and recommendations for evaluation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010 Oct;16(10):1362–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schubert MM, Williams BE, Lloid ME, Donaldson G, Chapko MK. Clinical assessment scale for the rating of oral mucosal changes associated with bone marrow transplantation. Development of an oral mucositis index. Cancer. 1992 May 15;69(10):2469–2477. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920515)69:10<2469::aid-cncr2820691015>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spinelli S, Chiodi S, Costantini S, et al. Female genital tract graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Haematologica. 2003 Oct;88(10):1163–1168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stratton P, Turner ML, Childs R, et al. Vulvovaginal chronic graft-versus-host disease with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2007 Nov;110(5):1041–1049. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000285998.75450.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hann DM, Denniston MM, Baker F. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: further validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(7):847–854. doi: 10.1023/a:1008900413113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989 May;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res. 1998 Jul;45(1 Spec):5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greinix HT, Pohlreich D, Maalouf J, et al. A single-center pilot validation study of a new chronic GVHD skin scoring system. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007 Jun;13(6):715–723. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell SA, Jacobsohn D, Thormann Powers KE, et al. A Multicenter Pilot Evaluation of the National Institutes of Health Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease (cGVHD) Therapeutic Response Measures: Feasibility, Interrater Reliability, and Minimum Detectable Change. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011 Apr 12; doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Treister NS, Stevenson K, Kim H, Woo SB, Soiffer R, Cutler C. Oral chronic graft-versus-host disease scoring using the NIH consensus criteria. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010 Jan;16(1):108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobsohn DA, Kurland BF, Pidala J, et al. Correlation between NIH composite skin score, patient-reported skin score, and outcome: results from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood. 2012 Sep 27;120(13):2545–2552. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-424135. quiz 2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inamoto Y, Pidala J, Chai X, et al. Assessment of joint and fascia manifestations in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2014 Nov 27;66(4):1044–1052. doi: 10.1002/art.38293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002 Jun;61(6):554–558. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inamoto Y, Chai X, Kurland BF, et al. Validation of measurement scales in ocular graft-versus-host disease. Ophthalmology. 2012 Mar;119(3):487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elad S, Zeevi I, Or R, Resnick IB, Dray L, Shapira MY. Validation of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) scale for oral chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010 Jan;16(1):62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bassim CW, Fassil H, Mays JW, et al. Validation of the National Institutes of Health chronic GVHD Oral Mucosal Score using component-specific measures. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014 Jan;49(1):116–121. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fassil H, Bassim CW, Mays J, et al. Oral chronic graft-vs.-host disease characterization using the NIH scale. Journal of dental research. 2012 Jul;91(7 Suppl):45S–51S. doi: 10.1177/0022034512450881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003 Apr;9(4):215–233. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobsohn DA, Schechter T, Seshadri R, Thormann K, Duerst R, Kletzel M. Eosinophilia correlates with the presence or development of chronic graft-versus-host disease in children. Transplantation. 2004 Apr 15;77(7):1096–1100. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000118409.92769.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baird K, Steinberg SM, Grkovic L, et al. National Institutes of Health chronic graft-versus-host disease staging in severely affected patients: organ and global scoring correlate with established indicators of disease severity and prognosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013 Apr;19(4):632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobsohn DA, Margolis J, Doherty J, Anders V, Vogelsang GB. Weight loss and malnutrition in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29(3):231–236. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parimon T, Madtes DK, Au DH, Clark JG, Chien JW. Pretransplant lung function, respiratory failure, and mortality after stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Aug 1;172(3):384–390. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-212OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walter EC, Orozco-Levi M, Ramirez-Sarmiento A, et al. Lung function and long-term complications after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010 Jan;16(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olivieri A, Cimminiello M, Corradini P, et al. Long-term outcome and prospective validation of NIH response criteria in 39 patients receiving imatinib for steroid-refractory chronic GVHD. Blood. 2013 Oct 23; doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-494278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmer J, Williams K, Inamoto Y, et al. Pulmonary symptoms measured by the national institutes of health lung score predict overall survival, nonrelapse mortality, and patient-reported outcomes in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014 Mar;20(3):337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalhoff H, Breidenbach R, Smith HJ, Marek W. Spirometry in preschool children: time has come for new reference values. Journal of physiology and pharmacology : an official journal of the Polish Physiological Society. 2009 Nov;60( Suppl 5):67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanik GA, Mineishi S, Levine JE, et al. Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor: enbrel (etanercept) for subacute pulmonary dysfunction following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012 Jul;18(7):1044–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bergeron A, Bengoufa D, Feuillet S, et al. The spectrum of lung involvement in collagen vascular-like diseases following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: report of 6 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 2011 Mar;90(2):146–157. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31821160af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Freudenberger TD, Madtes DK, Curtis JR, Cummings P, Storer BE, Hackman RC. Association between acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease and bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Blood. 2003 Nov 15;102(10):3822–3828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshihara S, Yanik G, Cooke KR, Mineishi S. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP), and other late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007 Jul;13(7):749–759. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, et al. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1994 Nov 16;272(19):1497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scanlon PD, Connett JE, Waller LA, et al. Smoking cessation and lung function in mild-to-moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lung Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Feb;161(2 Pt 1):381–390. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9901044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shanis D, Merideth M, Pulanic TK, Savani BN, Battiwalla M, Stratton P. Female long-term survivors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: evaluation and management. Seminars in hematology. 2012 Jan;49(1):83–93. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mitchell SA, Leidy NK, Mooney KH, et al. Determinants of functional performance in long-term survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010 Apr;45(4):762–769. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Treister N, Chai X, Kurland B, et al. Measurement of oral chronic GVHD: results from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013 Jan 28; doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matza LS, Swensen AR, Flood EM, Secnik K, Leidy NK. Assessment of health-related quality of life in children: a review of conceptual, methodological, and regulatory issues. Value Health. 2004 Jan-Feb;7(1):79–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.71273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]