Abstract

The mitochondrial transcription factor A, or TFAM, is a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) binding protein essential for genome maintenance. TFAM functions in determining the abundance of the mitochondrial genome by regulating packaging, stability, and replication. More recently, TFAM has been shown to play a central role in the mtDNA stress-mediated inflammatory response. Emerging evidence indicates that decreased mtDNA copy number is associated with several aging-related pathologies; however, little is known about the association of TFAM abundance and disease. In this Review, we evaluate the potential associations of altered TFAM levels or mtDNA copy number with neurodegeneration. We also describe potential mechanisms by which mtDNA replication, transcription initiation, and TFAM-mediated endogenous danger signals may impact mitochondrial homeostasis in Alzheimer, Huntington, Parkinson and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: TFAM, mitochondrial DNA, neurodegeneration

INTRODUCTION

Neurodegenerative diseases are heterogeneous disorders characterized by progressive and selective loss of neurons. Common examples include Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal dementia (ALS-FTD), and Huntington’s disease (HD). Progressive neuron degeneration results in currently irreversible deterioration of brain function. The pathologies of these neurodegenerative diseases share many similarities at a subcellular level, offering the hope that a common therapy could slow the decline in multiple neurodegenerative diseases [1, 2].

One common pathway proposed to contribute to neurodegenerative diseases is mitochondrial dysfunction [3, 4]. Mitochondria house the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes, comprised of the electron transport chain (Complexes I-IV) and the ATP synthase (Complex V), which are essential for efficient energy generation in the metabolically active neuronal tissue. Neurodegenerative disease can be caused by exposure to mitochondrial poisons [5] and PD can be caused by mutations in mitochondrial proteins [6], both of which can lead to mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction. In fact, mitochondrial dysfunction of unknown origin is well documented in ALS [7], PD [6], HD [8], and AD [9]. At the time of this writing, a PubMed search for “mitochondria” and “neurodegeneration” reviews exceeded 1,500 manuscripts, summarizing the abundance of evidence supporting a key role for mitochondrial pathobiology in neurodegeneration.

Despite the abundance of literature about mitochondria in neurodegeneration, our understanding of the underlying causes of mitochondrial dysfunction in these disorders is still limited [10]. The strongest evidence of mitochondrial involvement comes from the mutations that cause autosomal recessive forms of PD, in which genes that encode mitochondrial proteins or that regulate mitochondrial function, dynamics, biogenesis or turnover by mitophagy have been implicated [11]. These include PINK1, which encodes a mitochondrially targeted kinase [12, 13], PRKN/PARK2, which encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase recruited to depolarized mitochondria [14, 15], PARK7/DJ1, a chaperone that undergoes redox driven mitochondrial translocation [16, 17], and the mitochondrial protease HTRA2 [18]. Interestingly, there is also evidence from primary mitochondrial disorders for a causative role of mitochondrial dysfunction in some forms of neurodegeneration [19]. For example, patients who have mutations in mitochondrial polymerase γ, which exclusively replicates the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA), show an elevated risk of developing PD [20, 21]. In sporadic PD, similar processes to those delineated by studying causative gene mutations, such as mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity, quality control, organelle dynamics, mtDNA sequence and activation of cell death pathways implicate mitochondrial involvement in the development of the disease [6]. While the evidence supporting a role for mitochondrial dysfunction in other common sporadic diseases remains correlative [22], mechanistic pathways defined from studying genetic causes of neurodegenerative may converge with that of sporadic disease when aging or other factors impact shared pathways.

Primary mitochondrial disorders arise from mutations in the OXPHOS subunits, or the proteins and RNAs required for their expression, that are encoded in either the nucleus or the mtDNA [23]. MtDNA is a multi-copy, circular genome that is approximately 16.5 kb long and encodes 37 genes. Thirteen of these genes encode core protein subunits of Complexes I, III, IV, and V; twenty-two genes encode tRNAs and two genes encode rRNA that are required for the synthesis of those protein subunits. The sequence integrity of mtDNA is essential for mitochondrial respiratory function [24]. Studying primary mitochondrial diseases have revealed not only information on the function of specific proteins in the basic biology of mitochondria[25], but also that systemic mitochondrial dysfunction can nevertheless manifest in a tissue-specific manner. Likewise, Complex I deficiency has been found not only in brain regions that degenerate in PD [26], but also in the skeletal muscle and platelets of PD patients [27]. Moreover, multiple reports support the idea that low mtDNA copy number is associated with various human diseases, including obesity, cardiomyopathy, and cancer [28–31]. These data suggest that the preservation of mitochondrial genome copy number and sequence integrity may play a crucial role in replacing damaged mitochondrial complexes to maintain ATP levels and preserve cell viability under stress.

Mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) is a nuclear-encoded protein with an essential role in mtDNA metabolism. TFAM binds mtDNA in both sequence-specific and non-specific manner (reviewed in [32]). Sequence-specific binding to mtDNA promoter regions is required for initiating mitochondrial transcription, which may also serve as the RNA-primer for replication initiation. In addition, TFAM binds mtDNA in a sequence-independent manner to compact the genome. It is likely that both modes of mtDNA binding contribute to TFAM’s impact on mtDNA copy number. As a major factor in regulating mtDNA copy number, it is therefore timely to review the question ‘Is TFAM associated with neurodegeneration?’. The answer may help us to establish the potential of TFAM-related mitochondrial mechanisms in neurodegeneration and neuroprotection.

In this review, we examined the association of TFAM and mtDNA copy number with various neurodegenerative disorders. The term “TFAM” was used in a PubMed search in combination with each of the following terms: “Parkinson’s disease”, “Alzheimer’s disease”, “Huntington’s disease”, “amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”, “aging”, and “neurodegeneration”. Studies of TFAM in non-neural tissues were not included for tabulating changes in TFAM or mtDNA in neurodegenerative diseases. From this set, we focused on studies that examined TFAM alterations (mutation, deletion, changes in expression), during the progression of neurodegenerative disorders. We also compiled the changes in mtDNA content and/or TFAM protein levels in neurodegenerative disease samples relative to controls. After summarizing how TFAM functions to regulate mtDNA, and highlighting potential mechanisms by which alterations in TFAM may affect the progression of neurodegeneration, this review has been organized to delineate: 1) the impact of TFAM and mtDNA on the risk of neurodegenerative diseases, 2) changes in mtDNA or TFAM levels in neurodegenerative conditions, and 3) in vitro and in vivo evidence supporting a role for TFAM as a key regulator in neurodegeneration.

TFAM REGULATION OF mtDNA

Introduction to nuclear transcriptional regulation of mitochondrial content

Cells and tissues can adapt mitochondrial content in response to cellular energetic needs. Nutrient deficiency or mitochondrial dysfunction can trigger an upregulation in the transcription of nuclear encoded mitochondrial genes as a compensatory response called mitochondrial biogenesis [33]. Mitochondrial biogenesis is a process of increasing mitochondrial content that is primarily driven by changes in nuclear transcription. The complexity of this process is beyond the scope of this review, as there are amplification loops, pathway crosstalk, and elements of tissue specificity, but specific transcriptional regulators play a central role (ex. [34]). The PPARγ coactivator-1 (PGC-1) family of transcription co-activators (PGC-1α, PGC-1β, and PPRC1) interact with many transcription factors to regulate nuclear gene expression [35]. Importantly, PGC-1α activates expression of Nuclear Respiratory Factor (NRF)-1 and -2, which together act on many genes whose products are imported into mitochondria [36], including TFAM [37]. Upregulated TFAM transcription is generally concomitant with increased mtDNA, suggesting that TFAM links the nuclear transcription response to mtDNA content, coordinating mitochondrial biogenesis between the two genomes [37, 38].

The role of TFAM in regulating mtDNA replication, transcription, and packaging

TFAM was discovered as a mitochondrial protein that stimulated transcription of model templates in mitochondrial extracts [39]. TFAM is a nuclear-encoded protein that is synthesized in the cytoplasm and imported into the mitochondria [40]. The protein contains two high mobility group (HMG) box domains that insert into the DNA minor groove on the light strand promoter (LSP), heavy strand promoter 1 (HSP1), or non-specific regions of the mtDNA [41–43]. TFAM-binding causes a distortion of the mtDNA and results in DNA bending [42–46]. This distortion enables the specific binding of POLRMT (mitochondrial RNA polymerase) to the start site, where TFAM binds to the N-terminus of POLRMT to recruit TFB2M (mitochondrial Transcription Factor 2) while maintaining an open DNA complex arrangement that enables productive transcription initiation [47–51].

Transcripts are also used in priming DNA synthesis [52], implicating a TFAM function in the initiation of mtDNA replication. In brief, POLRMT synthesizes the nascent transcript from LSP, which either terminates or is post-transcriptionally processed at the conserved sequences blocks (CSB) I, II, or III [52, 53]. The RNA provides exposed 3′-end for the initiation of DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase γ. The nascent DNA frequently pauses, causing a structure termed the D-loop, which has a yet poorly defined function [54]. DNA synthesis that extends beyond the D-loop region has initiated replication. Thus, through the regulation of the LSP transcription initiation, TFAM levels can contribute to mtDNA replication initiation.

TFAM also binds non-specifically to all sequences of the mtDNA, thus coating the mitochondrial genome, providing structural stability and compacting the genome into nucleoid-like structures in vitro [45, 46, 55–58]. TFAM exists almost exclusively in a DNA-bound form [56, 57], as the DNA-free form is rapidly degraded in the mitochondrial matrix by the ATP-dependent mitochondrial Lon protease [59, 60]. TFAM protein abundance is thus tightly correlated with mtDNA content. The notable exception is the case of a POLRMT knockout, which reduces mtDNA content without changing TFAM protein amounts [61]. To summarize, through both its specific and non-specific sequence interactions with mtDNA, TFAM has multiple direct and indirect functions regulating mtDNA copy number to support mitochondrial respiratory function.

TFAM levels and mtDNA copy number

Numerous molecular and genetic models have demonstrated a direct connection between TFAM and mtDNA levels. Heterozygous mutation of TFAM results in ~40% decrease in mtDNA copy number in vivo, whereas the homozygous mutation is embryonically lethal [62]. TFAM heterozygous mice are more prone to metastasis in an intestinal cancer model [63], and TFAM heterozygous cells produce more inflammatory cytokines due to mitochondrial stress signaling [64]. Reciprocally, genetic TFAM overexpression increases mtDNA abundance such that the levels of TFAM are proportionally associated with the levels of mtDNA [65]. TFAM overexpression has also been observed as a protective modifier of diseases in numerous in vivo and in vitro models (reviewed in Campbell [66]). However, there is a limit to the benefit of TFAM overexpression. Titration of TFAM overexpression showed increases in mtDNA levels at low TFAM levels, but decreases as higher levels, suggestive of overcompaction of the genome cause replication inhibition [67, 68].

Regulation of TFAM stability or function through phosphorylation

Because levels of TFAM protein directly regulate mtDNA abundance, post-translational processes that alter the turnover or stability of TFAM protein could play an important role in regulating mtDNA content. Indeed, the mitochondrial matrix protease Lon selectively degrades TFAM protein and thus impacts mtDNA copy number [59]. Interestingly, the cAMP-dependent Protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylates TFAM at specific sites that impairs DNA-binding, causing TFAM release and allowing its degradation by Lon [60]. In contrast, extracellular signal regulated protein kinases (ERK1/2) phosphorylate a distinct site on TFAM that reduces promoter binding and transcription, but not non-selective mtDNA binding or mtDNA levels [69]. Besides phosphorylation, several studies concluded that TFAM is also post-translationally modified (PTM) by glycosylation [70], acetylation [71], and ubiquitination [72]. Although the numbers of TFAM PTMs described is growing, many of these have been identified through proteomics without further functional characterization, and the detailed mechanisms still need to be identified. As far as phosphorylation is concerned, both the PKA and ERK1/2 phosphosites act to reduce TFAM DNA-binding and thereby impact stability or function through different mechanisms.

TFAM and mtDNA-mediated inflammation

Recent evidence showed that decreased expression of TFAM (e.g. cells and tissues from TFAM heterozygous (TFAM+/-) mice) resulted in mtDNA stress signaling [64]. In primary TFAM heterozygous cells, the decreased TFAM protein levels caused an alteration mtDNA packaging, as evidenced by large mtDNA structures observed in primary TFAM heterozygous cells, allowing fragmented mtDNA to be released in the cytosol to activate the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) [64]. cGAS detects DNA from a broad range of intracellular viral and bacterial pathogens, also sensing mtDNA released to the cytosol upon mitochondrial stress. This activation results in an increased expression of interferon-stimulated genes and antiviral factors leading to a resistance to viral infections. The addition of TFAM, or other HMG box proteins such as bacterial HU and HMGB1, strongly potentiates cGAS signaling [73]. The mitochondrial genome can also increase innate immune responses, such as through the inflammasome or Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9)-related signaling (reviewed in West et al. [74]). Thus, any process that reduces TFAM function may activate mtDNA stress signaling, contributing to a pro-inflammatory environment that could alter disease trajectory and tissue function [74].

Overall premise supporting a role for mtDNA and TFAM in neurodegeneration and neuroprotection

MtDNA has a 10–17-fold higher mutation rate than that observed for nuclear DNA, implying that the mitochondrial genome is more vulnerable to accumulate oxidative damage that contributes to replication errors [75]. This vulnerability might be due to the mtDNA’s lack of complex chromatin organization, limited DNA repair activities, and/or proximity to the mitochondrial electron transport chain, a major source of cellular reactive oxygen species. Abnormalities in mtDNA were associated with numerous neurodegenerative diseases (reviewed in [76]). For example, mtDNA mutation, deletion, or depletion, as well as impaired transcription and replication, are observed in human samples from individuals affected by PD [77–81], AD [82–87], ALS [88], as well as in aging human or rat samples [89, 90]. It should be noted that not all investigators agree on whether changes in mtDNA mutation, deletion, or copy number are detected in their respective patient sample sets.

Overexpression analysis of mitochondrial TFAM showed a protective effect on cell survival or function in many models of disease that affect energetically demanding tissues, including type II diabetes [70, 91], heart attack [92], and heart failure [93]. Protective effects of TFAM overexpression is also reported in neuropathological conditions in model systems for aging-related hearing loss [94], memory loss [95], ALS [96], and AD [97, 98]. These novel results imply that TFAM has a protective role in several pathological conditions, but no clear underlying mechanisms have been identified.

CHANGES IN THE mtDNA LEVELS OR TFAM IN NEURODEGENERATIVE CONDITIONS

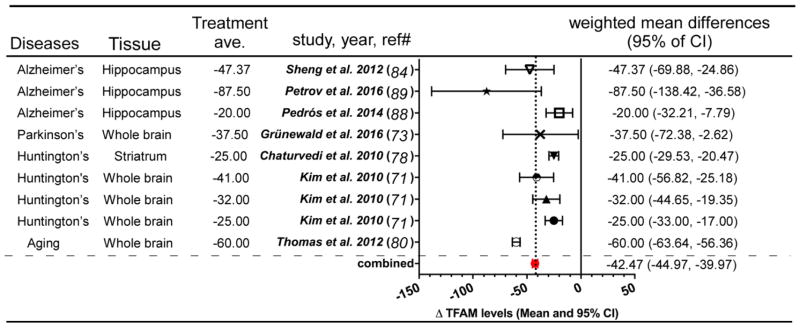

Decreased levels of mtDNA or TFAM in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and Huntington’s disease, as well as in Aging, were observed in multiple patient populations and animal models (Table 1). Using available data, we performed meta-analysis to combine and average measured mtDNA levels in neurodegenerative conditions from different studies (http://www.healthstrategy.com/meta/meta.pl) and found an average of ~29% relative to the control samples in each study (Figure 1). Using a similar meta-analysis approach, we found that TFAM protein or transcript levels (mostly protein levels) showed an average decrease of ~43% (Figure 2). Descriptions related to these observations are listed in Table 1. A limited number of studies examined TFAM and mtDNA levels in the same samples, supporting that reduction in mtDNA copy number is coupled to TFAM protein levels. This overview supports not only the known connection between TFAM and mtDNA, it re-enforces the hypothesis that mtDNA and TFAM content is associated with neuropathogenesis. In the following sections, we will discuss the evidence in two parts: 1) changes of mtDNA levels in different neurodegenerative conditions; and 2) changes in TFAM protein levels in different neurodegenerative conditions.

Table 1.

Evidence for mtDNA copy number changes in neurodegenerative disease.

| Catergory | Model | Tissue | mtDNA level | TFAM levels | Result/Responses | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | mRNA | ||||||

| Patient | iPD | midbrain section | ↓ (−27%) | ↓ (−38%) | - | 1. mitochondrial mass was unchanged 2. ↓ Complex I and II subunits, ↓mtDNA copy number and TFAM protein levels. 3.↓transcription/replication-associated mtDNA |

Grünewald et al. 2016 [101] |

| Mice | Alzheimer’s (APPswe/PS1dE9) | hippocampus | - | ↓ (−20%) | - | 1. ↓genes involved in insulin pathways 2.↓Ppargc1a mRNA and Pgc-1alpha protein levels in the hippocampus 3. 6 month-old APP/PS1 mice were glucose intolerant. |

Pedrós et al. 2014 [116] |

| Mice | Alzheimer’s (APPswe/PS1dE9) | hippocampus | - | ↓ (−88%) | - | 1. ↑ Prion protein level 2. ↓ Tfam, Pgc-1alpha, Nrf1 protein levels |

Petrov et al. 2016 [117] |

| Patient | Alzheimer’s | hippocampus | - | ↓ (−47%) | - | ↓NRF 1/2 and PGC-1alpha: ↓mitochondrial biogenesis protein levels | Sheng et al. 2012 [112] |

| Patient | Alzheimer’s | Brain | ↓ (−57%) | - | - | 1. ↑somatic mtDNA control region mutations 2. OXPHOS deficiency, ↑ROS production, ↑mtPTP 3. ↓synaptic connections through apoptosis |

Coskun et al. 2004 [82] |

| Mice | Huntington’s (R6/2, 7wks vs 10wks) | cerebral cortex | ↓ (−23%) | - | - | 1. ↑ mtDNA damage 2. DNA damage: mtDNA> nDNA, |

Acevedo-Torres et al. 2009 [104] |

| Mice | Huntington’s (R6/2, 7wks vs 12wks) | cerebral cortex | ↓ (−19%) | - | - | ||

| Mice | Huntington’s (NLS-N171-82Q) | striatum | ↓ (−25%) | - | ↓ (−25%) | 1. ↓ mtDNA and Pgc-1alpha, Nrf1/2, Tfam, mt-Cox-2, Ppar-delta, Creb and Err-alpha mRNA levels 2. microvacuolation in the neutrophil, gliosis and huntingtin aggregates. |

Chaturvedi et al. 2010 [106] |

| Patients | Huntington’s (Grade 2,3,4) | Bain lysate | ↓ (−10, −38, −62%) | ↓ (−25, −32, −41%) | - | 1. Mitochondrial loss and altered mitochondrial morphogenesis 2. ↑mitochondrial fission and ↓fusion |

Kim et al. 2010 [99] |

| Mice | Aging (4mon vs 17mon or 24 mon) | striatum | ↓ (−23%, −43%) | - | - | ↑ age-dependent mtDNA damage and nDNA damage | Acevedo-Torres et al. 2009 [104] |

| Mice | Aging (5mon vs 21mon) | brain | ↓ (−90%) | - | ↓ (−60%) | ↓ mtDNA copy number, Tfam and Sirt3 gene expression in brain | Thomas et al. 2012 [108] |

Alzheimer’s: Alzheimer’s disease, CREB: cAMP response element binding protein, ERR: Estrogen-related receptor, Huntington’s: Huntington’s disease, iPD: Idiopathic Parkinson Disease, mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA, mt-COX-2: mitochondrial Cytochrome c oxidase II, mtPTP: mitochondrial permeability transition pore, nDNA: nuclear DNA, NRF 1: Nuclear Respiratory Factor 1, OXPHOS: Oxidative phosphorylation, PGC1-alpha: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha, PPAR: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, SIRT 3: Sirtuin 3, TFAM: mitochondrial transcription factor A

Figure 1.

mtDNA copy number changes in different neurodegenerative diseases. Data from indicated studies were entered into meta-analysis calculator and graphically represented (http://www.healthstrategy.com/meta/meta.pl). Red dot and vertical dashed line: shows the calculated average of values of 29% reduction in mtDNA levels across the indicated studies. Values weighted to reflect sample number. Ave.: average, CI: confidence interval, ΔmtDNA levels: difference in mtDNA levels in patient group relative to control group

Figure 2.

TFAM expression changes in different neurodegenerative diseases. Data from indicated studies were entered into meta-analysis calculator and graphically represented (http://www.healthstrategy.com/meta/meta.pl). Red dot and vertical dashed line: shows the calculated average of values of 42% reduction in TFAM levels across the indicated studies. Values weighted to reflect sample number. Ave.: average, CI: confidence interval, Δ TFAM levels: difference in TFAM levels in patient group relative to control group.

Evidence for decreased mtDNA copy number in neurodegenerative disease patients and animal models

Reduction in mitochondrial genome content has been observed in multiple human samples (HD, AD, and idiopathic PD (iPD)). In post mortem HD patient lysates, the extent to which mtDNA levels were decreased depended on the grade of disease, showing a progressive decline of 10% (Grade 2), 38% (Grade 3), or 68% (Grade 4) compared to age-matched control subjects [99]. In AD patients samples, which is the most common neurodegenerative disease, mtDNA levels are reduced by 57% in the frontal cortex brain when compared to control patients [82]. Furthermore, AD patients also appeared to have an increased number in somatic mtDNA mutations. These mutations were located in elements involved in mtDNA L-strand transcription and/or H-strand replication and were associated with reductions in the mtDNA L-strand mRNA mt-ND6 (Mitochondrially Encoded NADH: Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase Core Subunit 6) and mtDNA copy number. In micro-dissected pyramidal neurons from the hippocampus of AD patients, mtDNA levels were decreased as were associated markers of mitochondrial biogenesis [100]. iPD patients also showed 27% reduction in mtDNA levels from midbrain sections [101]. Recently, an extensive review of mtDNA sequence and abundance in aged brain provided a compelling evidence for an association between mtDNA copy number reduction to neurodegeneration in AD and Creutzfeldt-Jakob Jacob disease [87]. Interestingly, this study suggested that mtDNA mutation is not a significant contributor to mitochondrial dysfunction in those tissues.

A growing number of studies demonstrated the influence of mtDNA copy number reduction on neurodegeneration in animal models (Table 1). HD is exclusively an inherited disorder caused by a mutation in the Huntingtin protein that results in glutamine expansion in the protein [102]. R6/2 was the first HD mouse model, generated to express exon 1 of the human HD gene with around 150 glutamine codon (CAG) repeats, which causes a progressive neurological phenotype [103]. In the cerebral cortex R6/2 mice, Acevedo-Torres and colleagues found both a significant reduction of mtDNA levels of ~23% and an increase in mtDNA damage relative to controls [104]. They also demonstrated that the reduction of mtDNA is connected to mtDNA damage, which may be an early biomarker for HD neurodegeneration. Another HD mimic-transgenic mouse model is NLS-N171-82Q, which expresses the first 171 amino acids of Huntingtin with an 82-glutamine expansion. This mouse model demonstrated multiple degenerative phenotypes such as losses of motoric function, hypoactivity, and abbreviated life-span [105]. In the study of Chaturvedi et al., striatum mtDNA levels were significantly reduced by 25% in the NLS-N171-82Q HD model relative to the control group [106]. They also found that this HD model exhibited reduced expression of nuclear-encoded genes representing mitochondrial biogenesis markers, such as PGC-1α, and several Complex IV subunits.

Despite the low prevalence of neurodegeneration in normally aged mice [107], aged rodent studies remain relevant for understanding the context of genetic and idiopathic neurodegeneration. Acevedo-Torres et al. compared brain-mtDNA levels in 4-month-old mice with 17- or 24-month-old C57BL/6 mice and found that mtDNA levels were decreased in the 17 and 24-month aged mice (33% and 43% reduction, respectively,) accompanied by increased mtDNA damage in the striatum of the brain [104]. Similarly, Thomas et al. found that aging produced a marked 90% reduction in mtDNA copy number relative to the control group in the mouse brain (and to a lesser degree in the heart) [108]. Not only mtDNA levels, but also mitochondrial biogenesis signaling, is substantially reduced in aging brain and heart compared to the control group. Thus, the study of aging remains fundamental to understanding how mtDNA abundance may impact the development and progression of age-related neurodegenerative diseases.

As a caveat, studies of mtDNA copy number in human brains at various ages have yielded mixed results [109, 110]. Different regions of the brain have also been shown to exhibit significant differences in mtDNA level within a single individual [111], suggesting that sample acquisition may account for some of the variation. Alternatively, uniformity within inbred animal strains may enable the detection of age-related changes, while the genetic diversity among human subjects masks that change. Because none of the human studies are longitudinal in the same individual, we cannot account for changes within an individual during the aging process.

Evidence for TFAM expression changes in neurodegenerative disease models

TFAM protein levels are a central regulator of mtDNA copy number [65], which has multiple associations with neurodegeneration, prompting a review of TFAM levels (mostly protein levels) in association with neuropathological findings in patient samples and animals. AD is the most common neurodegenerative disease whose gross pathology involves cortical and hippocampal shrinkage, enlargement of ventricles, and frequent evidence of extracellular β-amyloid plaques or intracellular Tau neurofibrillary tangles. Sheng et al. showed that relative to control samples, the hippocampus of AD patient brains, but not the cerebellum, contained a 50% reduction in TFAM protein levels, which was concomitant with impaired mitochondrial biogenesis evidenced by decreased NRF1, NRF2 and PGC-1α protein levels [112]. β-amyloid is a cleavage product of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), which mice do not readily make. Many transgenic mice lines have been created to overcome this challenge (reviewed in [113]). A common animal model for study is the APPswe/PS1dE9 double transgenic mouse, which neuronally expresses a chimeric APP (KM670/671NL) and the mutant human presenilin 1 protein harboring a deletion in exon 9. In this mutant mouse model the production of human β-amyloid is increased [114], leading to more visible plaque formation, memory loss, and a moderate behavior phenotype [115]. APPswe/PS1dE9 mice have a 20% to 87.5% reduction in TFAM protein levels in the hippocampus compared to the control group [116, 117]. The levels of mtDNA were not determined in either of these studies and we could not find another AD mouse model that reported levels of TFAM protein.

TFAM protein levels were also measured in HD patient samples and animal models, mouse aging, and iPD patients. Kim et al. examined the TFAM protein levels in Grade 2, 3, and 4 of HD patients, which were reduced by 25, 32, and 41%, respectively, compared to age-matched control subjects [99]. In HD patients, the reduction of TFAM protein levels was accompanied by reduced nuclear mitochondria biogenesis markers, dampened number of mitochondria, altered mitochondrial morphogenesis, increased mitochondrial fission, and reduced mitochondrial fusion. In the HD transgenic mouse NLS-N171-82Q, TFAM showed a 25% reduction of TFAM mRNA levels compared to the wild-type mice along with reduced nuclear mitochondrial biogenesis transcription signatures and mtDNA [106]. Aged mice (21 months) had 60% less TFAM expression in brain preparations relative to that of 5-month old control mice [108]. Moreover, iPD patients had around 37.5% reduction in TFAM protein levels and loss of the respiratory chain complexes in individual dopaminergic neurons [101]. IPD patients also showed a significant reduction in Complex I and II subunits compared to the age-matched control group. These changes are correlated with increased ERK1/2 activation in human iPD midbrain neurons [118], which drives autophagic turnover of mitochondria [119, 120] in concert with suppression of TFAM-mediated mtDNA transcription [69] and mitochondrial protein synthesis [121]in cellular models of iPD. The collection of evidence is still indirect, but point to an alteration in mitochondrial biogenesis that reduces TFAM protein levels in some patient samples and many animal models. Whether evidence supports a central role for TFAM levels in the susceptibility to disease will be discussed in a later section.

THE ROLE OF TFAM IN NEURODEGENERATION

The TFAM genetics in neurodegenerative diseases

There are several reports illustrating the association of TFAM gene mutations or polymorphisms, mostly from two TFAM mutations (rs1937 and rs2306604), and the development of PD, dementia, AD, and HD (Table 2). TFAM SNP rs2306604 is located in intron 4, but which allele is associated with each disease is still disputed. According to Gaweda-Walerych et al., the G allele is associated with PD risk [122], whereas Gatt et al. reported that the A allele is associated with PD in males [123]. Günther et al. [124] and Belin et al. [125] also reported that rs2306604A is connected with a moderate risk factor for AD. There is also a report arguing that there is no association between rs2306604 and late-onset AD [126]. For TFAM rs1937, Günther et al. observed that the G allele moderately increases risk for AD [124], while Zhang et al. reported that the C allele provides a protective role against late-onset of AD [126]. Although there are continuously new reports about TFAM genetics on the risk of neurodegeneration, it is not yet possible to conclude which allele is a specific major risk of neurodegeneration due a lack of consensus among studies. It also remains unknown whether or not either of these alleles are able to impact TFAM protein levels or function.

Table 2.

TFAM genetic variants associated with risk or progression in neurodegenerative patients

| Diseases | Gene locus | TFAM SNP | subjects | Key observation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | 10q21.1 | rs2306604 | PD patients (n=326) and controls (n=316) | TFAM SNP rs2306604 (IVS4 + 113A > G) has been associated with PD | Gaweda-Walerych et al. 2010 [122] |

| PD, dementia | 10q21.1 | rs2306604 | DLB (n=72) or PDD (n=63) and control (n=106) | 1. TFAM SNP rs2306604 genotype frequency was significantly different to controls in PDD but not DLB. 2. TFAM SNP rs2306604 A allele was associated with PDD but not DLB. 3. rs2306604 A allele was strongly associated with PDD in males but not in females. 4. Genetic factors predisposing to dementia may differ in PDD and DLB. |

Gatt et al. 2013 [123] |

| AD | 10q21.1 | rs1937 and rs2306604 | AD (n=372) patients and non-demented control (n=295) | TFAM haplotype containing rs1937 G (for S12) and rs230660 A may be a moderate risk factor for AD. | Günther et al. 2004 [124] |

| PD | 10q21.1 | rs1937 and rs2306604 | AD (n=423) and control (n=313) or PD (n=300) and control (n=253) from Sweden | TFAM rs2306604 A-allele could be a moderate risk factor for AD | Belin et al. 2007 [125] |

| AD | 10q21.1 | rs1937 and rs2306604 | LOAD (n=394) and control (n=390), A large Chinese cohort | 1. Significant difference was found in genotype and allele frequencies of the SNP rs1937 between LOAD patients and controls. 2. The C allele of rs1937 acted as a protective factor of LOAD 3. No significant association was observed between rs2306604 and LOAD. 4. The variations in TFAM are involved in the pathogenesis of sporadic LOAD in Han Chinese. |

Zhang et al. 2011 [126] |

| AD | 10q21.1 | rs1937 | AD patients (n=161), non-AD (n=96) patient controls and healthy controls (n=192) | 1. BER is the major pathway for repairing oxidative damage events in chromosomal and mitochondrial DNA. 2. Deficient BER activity has been detected in brain ageing and neurodegeneration. 3. Alleles in mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) is associated with reduced cognitive performance. 4. SNPs in BER and TFAM genes are potential diagnostic biomarkers for cognitive function |

Lillenes et al. 2017 [138] |

| HD | 10q21.1 | rs1937 and rs2306604 | HD patients (n=401) Germany | TFAM showed nominally significant association with AO of HD. | Taherzadeh-Fard et al. 2011 [139] |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease, AO: age at onset, BER: Base excision repair, DLB: dementia with Lewy bodies, LOAD: late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, PD: Parkinson’s disease, PDD: Parkinson’s disease dementia

In vivo models of TFAM deficiency and its neurodegenerative phenotypes

A growing number of studies demonstrated the ability of ‘loss-of-function’ or ‘gain-of-function’ manipulations of TFAM expression to modify neurodegenerative phenotypes (Table 3). TFAM knockout is embryonic-lethal; therefore, several groups utilized neuron-specific knockout as ‘loss-of-function’ models of TFAM in mice. The first of such TFAM models was the mitochondrial late-onset neurodegeneration (MILON) mouse, which used CaMKIIa-CRE to disrupt TFAM in the forebrain, including the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus [127]. The MILON mouse brain showed a reduction of ~50% in mtDNA levels, accompanied by progressive nerve cell loss, apoptosis, and gliosis in the neocortex and hippocampus. Also, MILON mice were considerably more vulnerable to an excitotoxic challenge. The results demonstrated that a complete loss of TFAM would render neurons more vulnerable to stress, leading to neurodegenerative phenotypes.

Table 3.

The evidence for manipulation TFAM by gain-of-function and loss-of-function in vivo and in vitro

| Category | Test model | TFAM | Responses and Physiological effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Late-onset neurodegeneration | TFAM KO in forebrain neurons (MILON) | 1. ↓ mtDNA in neocortex and hippocampus 2. corticohippocampal nerve cell loss and gliosis 3. ↓ induction of antioxidant defenses 4. excitotoxic stress induces marked neuronal cell death |

Sörensen et al. 2001 [127] |

| In vivo | PD | TFAM KO in dopamine (MitoPark) | 1. ↓ mtDNA and ↓respiratory chain deficiency in midbrain DA neurons. 2. respiratory chain dysfunction in DA neurons leads to PD |

Ekstrand et al. 2007 [128] |

| In vivo | PD | TFAM KO in dopamine (MitoPark) | Progressive loss of motor function, intraneuronal inclusions, and eventually neuronal cell death. | Galter et al. 2010 [129] |

| In vivo | PD | TFAM KO in dopamine (MitoPark) | 1. cell body mitochondria are enlarged 2. fragmented and striatal mitochondria are reduced in number and size |

Sterky et al. 2011 [130] |

| In vivo | PD | TFAM KO in dopamine (MitoPark) | 1. slow progressing parkinsonian phenotype (~12 weeks) 2. Release of DA was imparied in early stage. 3. Nigral DA neurons lacked characteristic pacemaker activity. 4. ↓ hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel function. |

Good et al. 2011 [131] |

| In vivo | AD (3xTg-AD) | TFAM OE | 1. improved cognitive function 2.↓ 8-oxoguanine and oxidized form of guanine in the mtDNA and intracellular Aβ 3.↑ Transthyretin (known to inhibit Aβ aggregation) expression |

Oka et al. 2016 [98] |

| In vivo | Aging (24mon C57BL/6) | TFAM OE | 1. ↓ age-dependent lipid peroxidation, ↑Complex I, IV activities in the brain. 2. Deficits of the motor learning memory, the working memory, and the hippocampal LTP were improved. 3.↓ Il-1beta immunofluorescences activity and ↓ mtDNA damages in microglia. 4.↓ Il-1beta protein levels in brain from LPS treated aged TG mice |

Hayashi et al. 2008 [95] |

| In vivo | Aging (20mon C57BL/6) | Recombinant human TFAM treatment | 1. ↑ mitochondrial respiration in brain, heart, muscle 2. ↑ mtDNA, mitochondrial RNA polymerase (Pplrmt mRNA expression) in brain 3. ↑ Pgc1-alpha in heart 4. ↓ oxidative stress damage to brain proteins and improved memory function |

Thomas et al. 2012 [108] |

| In vitro | AD (model of AD using neurons derived from iPSCs) | Recombinant human TFAM treatment | 1. improved mitochondrial dysfunction, accumulation of 8-oxoguanine, single-strand breaks in mtDNA 2. ↑ expression of Transthyretin (known to inhibit Aβ aggregation) 3. ↓intracellular Aβ |

Oka et al. 2016 [98] |

| In vitro | AD | TFAM OE | 1. ↓ROS and reversed the reduction in cytochrome c oxidase activity, ATP production induced by Abeta1-42. 2. maintain the mtDNA nucleoid formation and mtDNA copy number |

Xu et al. 2009 [97] |

| In vitro | PD | TFAM OE | 1. ↓abrogated MPP(+)-mediated damages on mitochondria and insulin signaling 2. recover nigrostriatal neurodegeneration. |

Piao et al. 2012 [134] |

| In vitro | PD | mtDNA-complexed TFAM | ↑ mitochondrial functions deregulated in cybrids from PD patients (↑mtDNA, mtRNA, TFAM, ETC protein levels-mitochondrial biogenesis). | Keeney et al. 2009 [135] |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease, DA: dopamin, KO: knock-out, LTP: long-term potentiation, MPP: 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium, PD: Parkinson’s disease, POLMRT: mitochondrial RNA polymerase

Use of the dopamine transporter promoter to drive CRE-mediated TFAM knockout in dopaminergic neurons resulted in a Parkinson’s like neurodegenerative phenotype [128]. These mice, called MitoPark mice, appear healthy at birth, but develop progressive degeneration of dopamine neurons as adults accompanied by depletion of striatal dopamine and impaired spontaneous locomotion. Pathological analysis revealed intraneuronal inclusions, and eventually neuronal cell death [129]. Additional studies showed that TFAM depletion in the MitoPark mice led to fragmentation of the mitochondrial network, formation of large mitochondrial aggregates, and impaired transport of mitochondria to the nerve terminals in the striatum [130]. MitoPark mice also exhibit functional changes in the substantia nigra pars compacta dopamine neurons, with slow progression of Parkinsonian phenotype and motor impairment [131]. Furthermore, hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel function and release of dopamine were reduced in young, presympotomatic MitoPark brain slices, indicating that altered nigrostriatal function precedes behavioral Parkinsonian symptoms. Whether partial depletion of TFAM, such as conditional induction of TFAM heterozygosity, can modify other models of neurodegenerative diseases still needs to be established.

Evidence for TFAM overexpression or TFAM enzyme replacement therapy in addressing neurodegenerative disease models

From the above discussion, it is evident that TFAM and mitochondrial genome levels frequently decline in both patient samples and animal models of neurodegeneration, and genetic TFAM deficiency can cause neurodegeneration. However, these results could also be explained by indirect effects of decreased mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction, respectively. TFAM overexpression (OE) has been used as a tool to demonstrate the importance of TFAM in preserving a healthy mitochondrial genome. Indeed, TFAM OE improved the phenotypes in models with mitochondrial disorders [132, 133]. Interestingly, TFAM OE in wild-type mice increased the mtDNA content but did not increase mitochondrial respiratory function [65]. The use of TFAM OE thus allows the assessment of direct effects of TFAM on mtDNA in aging-related disorders and in neurodegenerative disease models (Table 3). Notably, whole body TFAM OE improved hippocampal long-term potentiation as well as motor learning memory in mice at 24 months of age, associated with a reduction of lipid peroxidation and improved Complex I and IV activities in the brain [95]. Furthermore, the Interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), which is an important mediator of the inflammatory response and mtDNA damage, was decreased in microglia [95]. In the 3xTg mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease (PSEN1 PS1M146V, APPswe, and MAPT P301L triple transgenic), TFAM OE improved cognitive function and reduced both mtDNA oxidative damage and Aβ accumulation [98]. In a cell-based model of Aβ toxicity, human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell lines showed increased oxidative stress and decreased mitochondrial respiratory function, both of which were significantly improved when TFAM was overexpressed [97]. Using a cell-based model of toxicant-induced Parkinson’s disease, the inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory function by exposure to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) was significantly reduced when TFAM was overexpressed in human SH-SY5Y cells [134]. In light of the number of studies showing that TFAM protects against diseases with oxidative stress and mitochondrial components (see [32] and above references), any intervention causing increase of TFAM levels, and therefore mtDNA stability and enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis, could be a viable approach to slow the progression of neurodegenerative diseases.

Non-genetic approaches, such as recombinant protein treatment, have also been used to test TFAM-mediated protection in neurodegenerative models. Recombinant human TFAM (rhTFAM) treatment can stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis in human cells derived from sporadic Parkinson’s disease patients [135]. PD cybrids, which carry the mtDNA of PD patients but have a cell line nucleus, showed a significant reduction in the electronic transport chain of Complex I, increased oxidative stress, respiratory impairment, and reduced mtDNA levels. These cells also spontaneously formed Lewy body inclusions, Treatment with TFAM complexed with mtDNA increased mitochondrial function as evidenced by induction of mtDNA, mtRNA, TFAM, and respiratory chain protein levels. In animal models of aging, treatment of 20-month aged mice with rhTFAM stimulated mitochondrial biogenesis and mtDNA gene expression in the absence of any apparent systemic toxicity [108]. Increases in mitochondrial oxidative metabolism were mirrored by improvements in spatial learning and memory in aged mice. In a human cell culture model of Alzheimer’s disease (PS1 P117L), cells treated with rhTFAM (but not a control form that cannot be imported into mitochondria) reduced mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and consequently, reduced mtDNA oxidative damage and prevented Aβ accumulation [98]. The protective effect of overexpressed TFAM is expected to be largely dependent on its role in maintaining the mtDNA nucleoid formation and mtDNA copy number, or in regulating mtRNA synthesis and mitochondrially-encoded protein synthesis. These findings support further investigations for a beneficial effect of rhTFAM in human aging and neurodegeneration

UNRESOLVED QUESTIONS

There are two primary limitations to the argument that TFAM is central to neurodegenerative disease. First, we lack a complete understanding of the regulation of mtDNA content in neurons. Our current understanding primarily comes from the response of skeletal muscle to mitochondrial dysfunction, where the adaptive gene expression increases mitochondrial content and TFAM gene expression. Interestingly, we are unaware of evidence demonstrating that TFAM upregulation is necessary for this coupling of mtDNA levels to nuclear responses of mitochondrial biogenesis. Other factors may play the primary role in establishing the link between the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes (i.e. TFAM transcriptional coordination is true but irrelevant). Additional studies of the coordination of TFAM transcription, TFAM protein levels, and mtDNA copy number, perhaps at the single cell level, will be necessary to reach a quantitative understanding of the TFAM-mtDNA connection. Also, neurons may show different responses to a given injury compared to proliferative or glycolytic cell types [136, 137]. Thus, studies using iPSC-derived tissues or organoids may enable a more comprehensive mechanistic picture of the transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanism at play in human diseases, allowing the delineation of specialized regulatory mechanisms operating in post-mitotic neurons.

Second, the evidence provided in Figure 1 & 2 summarize a trend toward a generalized maladaptive gene expression, rather than changes specific or unique to TFAM. Such is the limitation with associative studies. However, both of these caveats are mitigated by the observation that TFAM overexpression is sufficient to elevate mtDNA levels and protect against disease. From a practical perspective, rhTFAM, potentially via viral delivery, may represent a potential modifier of disease course. Nonetheless, the exact mechanisms by which disease progression is arrested by elevating TFAM warrants further investigation.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES

Mitochondrial dysfunction, in conjunction with altered mitochondrial dynamics, is a major factor observed in neurodegenerative diseases. In this review, we compiled the literature indicating that changes in mtDNA and TFAM protein levels occur in multiple neurodegenerative diseases, and the impact of gain-of-function and loss-of-function manipulations of TFAM in aging and neurodegenerative models. In neurodegenerative model studies, the overall levels of mtDNA are reduced by ~30%, while TFAM protein levels are reduced by ~50%. Cell type-specific TFAM ablation is sufficient to cause mice to have a late-onset of phenotypes reminiscent of common neurodegenerative diseases. In both cell and animal models of neurodegeneration, TFAM overexpression and TFAM enzyme replacement therapy measurably improved neural function and content. These data, when considered along with the genetic evidence drawn from primary mitochondrial diseases and monogenic forms of Parkinson’s disease, strongly implicate alterations in mitochondrial content, function or dynamics in the initiation or progression of neurodegenerative diseases.

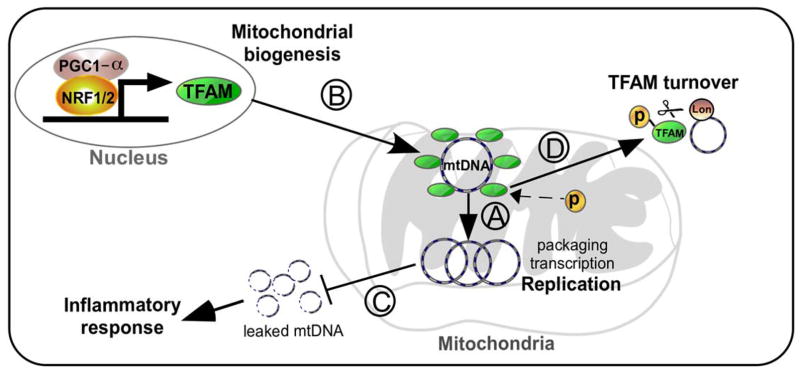

As illustrated in Figure 3, the roles of TFAM in neurodegenerative diseases and potential mechanisms of action include the following: A) control of mtDNA copy number via TFAM; B) TFAM-mediated induction of mtDNA copy number and transcription in response to increased mitochondrial biogenesis by transcription factor NRF1/2 and/or transcription co-factor PGC-1α; C) prevention of mtDNA damage and release into the cytosol which leads to inflammatory signaling; and D) the impact on mtDNA or mtRNA levels due to TFAM phosphorylation or other post-translational modifications. Because altered TFAM and mtDNA levels are associated with multiple models of neurodegeneration, we suggest that the mechanisms that regulate TFAM, such as gene expression, post-translational modification, and proteolysis may be key mechanisms in the progression of the diseases. These discoveries support a potential benefit of TFAM-related treatment strategies as a novel therapy in future clinical studies.

Figure 3.

Working model explaining how TFAM could impact the progression of neurodegenerative diseases through alteration of mtDNA dynamics. A) TFAM controls mtDNA copy number though regulation of mtDNA replication, transcription, and packaging. B) mtDNA copy number may increase during mitochondrial biogenesis through increased TFAM levels. C) Adequate levels of TFAM are required to prevent mtDNA release into cytoplasm that could elicit an inflammatory response. D) mtDNA turnover or transcription may be modulated by TFAM post-translational modification. Enhancing TFAM functions or decreasing its turnover may serve to slow or prevent several neurodegenerative diseases. NRF1: Nuclear Respiratory Factor 1, TFAM: Mitochondrial Transcription Factor A, mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA

Acknowledgments

Research in the authors’ laboratories have been supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (Grants GM110424, AG026389, NS065789, TR000503, NS101628).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflicts of interest: Inhae Kang

No conflicts of interest: Charleen T. Chu

No conflicts of interest: Brett A. Kaufman

References

- 1.Bredesen DE, Rao RV, Mehlen P. Cell death in the nervous system. Nature. 2006;443:796–802. doi: 10.1038/nature05293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubinsztein DC. The roles of intracellular protein-degradation pathways in neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:780–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beal MF. Mitochondria take center stage in aging and neurodegeneration. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:495–505. doi: 10.1002/ana.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright AF, Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Roman AJ, Shu X, Vlachantoni D, McInnes RR, Riemersma RA. Lifespan and mitochondrial control of neurodegeneration. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1153–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon JR, Greenamyre JT. The role of environmental exposures in neurodegeneration and neurodegenerative diseases. Toxicol Sci. 2011;124:225–50. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bose A, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2016;139(Suppl 1):216–231. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith EF, Shaw PJ, De Vos KJ. The role of mitochondria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci Lett. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jodeiri Farshbaf M, Ghaedi K. Huntington’s Disease and Mitochondria. Neurotox Res. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12640-017-9766-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grimm A, Friedland K, Eckert A. Mitochondrial dysfunction: the missing link between aging and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Biogerontology. 2016;17:281–96. doi: 10.1007/s10522-015-9618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giannoccaro MP, La Morgia C, Rizzo G, Carelli V. Mitochondrial DNA and primary mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2017;32:346–363. doi: 10.1002/mds.26966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hauser DN, Hastings TG. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease and monogenic parkinsonism. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;51:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dagda RK, Pien I, Wang R, Zhu J, Wang KZ, Callio J, Banerjee TD, Dagda RY, Chu CT. Beyond the mitochondrion: cytosolic PINK1 remodels dendrites through protein kinase A. J Neurochem. 2014;128:864–77. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazarou M, Sliter DA, Kane LA, Sarraf SA, Wang C, Burman JL, Sideris DP, Fogel AI, Youle RJ. The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature. 2015;524:309–314. doi: 10.1038/nature14893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shlevkov E, Kramer T, Schapansky J, LaVoie MJ, Schwarz TL. Miro phosphorylation sites regulate Parkin recruitment and mitochondrial motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E6097–E6106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612283113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens DA, Lee Y, Kang HC, Lee BD, Lee YI, Bower A, Jiang H, Kang SU, Andrabi SA, Dawson VL, Shin JH, Dawson TM. Parkin loss leads to PARIS-dependent declines in mitochondrial mass and respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:11696–701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500624112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas KJ, McCoy MK, Blackinton J, Beilina A, van der Brug M, Sandebring A, Miller D, Maric D, Cedazo-Minguez A, Cookson MR. DJ-1 acts in parallel to the PINK1/parkin pathway to control mitochondrial function and autophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:40–50. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Junn E, Jang WH, Zhao X, Jeong BS, Mouradian MM. Mitochondrial localization of DJ-1 leads to enhanced neuroprotection. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:123–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bogaerts V, Nuytemans K, Reumers J, Pals P, Engelborghs S, Pickut B, Corsmit E, Peeters K, Schymkowitz J, De Deyn PP, Cras P, Rousseau F, Theuns J, Van Broeckhoven C. Genetic variability in the mitochondrial serine protease HTRA2 contributes to risk for Parkinson disease. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:832–40. doi: 10.1002/humu.20713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turnbull HE, Lax NZ, Diodato D, Ansorge O, Turnbull DM. The mitochondrial brain: From mitochondrial genome to neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:111–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luoma P, Melberg A, Rinne JO, Kaukonen JA, Nupponen NN, Chalmers RM, Oldfors A, Rautakorpi I, Peltonen L, Majamaa K, Somer H, Suomalainen A. Parkinsonism, premature menopause, and mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma mutations: clinical and molecular genetic study. Lancet. 2004;364:875–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16983-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeve A, Meagher M, Lax N, Simcox E, Hepplewhite P, Jaros E, Turnbull D. The impact of pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations on substantia nigra neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:10790–801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3525-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zsurka G, Kunz WS. Mitochondrial involvement in neurodegenerative diseases. IUBMB Life. 2013;65:263–72. doi: 10.1002/iub.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craven L, Alston CL, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. Recent Advances in Mitochondrial Disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2017;18:257–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091416-035426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Picard M, Wallace DC, Burelle Y. The rise of mitochondria in medicine. Mitochondrion. 2016;30:105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McFarland R, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial disease--its impact, etiology, and pathology. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;77:113–55. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)77005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schapira AH, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Clark JB, Jenner P, Marsden CD. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 1990;54:823–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann VM, Cooper JM, Krige D, Daniel SE, Schapira AH, Marsden CD. Brain, skeletal muscle and platelet homogenate mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1992;115(Pt 2):333–42. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu M, Zhou Y, Shi Y, Ning L, Yang Y, Wei X, Zhang N, Hao X, Niu R. Reduced mitochondrial DNA copy number is correlated with tumor progression and prognosis in Chinese breast cancer patients. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:450–7. doi: 10.1080/15216540701509955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Memon AA, Zoller B, Hedelius A, Wang X, Stenman E, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Quantification of mitochondrial DNA copy number in suspected cancer patients by a well optimized ddPCR method. Biomol Detect Quantif. 2017;13:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bdq.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karamanlidis G, Nascimben L, Couper GS, Shekar PS, del Monte F, Tian R. Defective DNA replication impairs mitochondrial biogenesis in human failing hearts. Circ Res. 2010;106:1541–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JY, Lee DC, Im JA, Lee JW. Mitochondrial DNA copy number in peripheral blood is independently associated with visceral fat accumulation in healthy young adults. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:586017. doi: 10.1155/2014/586017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell CT, Kolesar JE, Kaufman BA. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mitochondrial transcription initiation, DNA packaging, and genome copy number. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819:921–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jornayvaz FR, Shulman GI. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem. 2010;47:69–84. doi: 10.1042/bse0470069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Auwerx J. Regulation of PGC-1alpha, a nodal regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:884S–90. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finck BN, Kelly DP. PGC-1 coactivators: inducible regulators of energy metabolism in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:615–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI27794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scarpulla RC. Metabolic control of mitochondrial biogenesis through the PGC-1 family regulatory network. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1269–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Virbasius JV, Scarpulla RC. Activation of the human mitochondrial transcription factor A gene by nuclear respiratory factors: a potential regulatory link between nuclear and mitochondrial gene expression in organelle biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1309–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Picca A, Lezza AM. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis through TFAM-mitochondrial DNA interactions: Useful insights from aging and calorie restriction studies. Mitochondrion. 2015;25:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher RP, Clayton DA. A transcription factor required for promoter recognition by human mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Accurate initiation at the heavy- and light-strand promoters dissected and reconstituted in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:11330–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garstka HL, Schmitt WE, Schultz J, Sogl B, Silakowski B, Perez-Martos A, Montoya J, Wiesner RJ. Import of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) into rat liver mitochondria stimulates transcription of mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5039–47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ngo HB, Kaiser JT, Chan DC. The mitochondrial transcription and packaging factor Tfam imposes a U-turn on mitochondrial DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1290–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ngo HB, Lovely GA, Phillips R, Chan DC. Distinct structural features of TFAM drive mitochondrial DNA packaging versus transcriptional activation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3077. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubio-Cosials A, Sidow JF, Jimenez-Menendez N, Fernandez-Millan P, Montoya J, Jacobs HT, Coll M, Bernado P, Sola M. Human mitochondrial transcription factor A induces a U-turn structure in the light strand promoter. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1281–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malarkey CS, Bestwick M, Kuhlwilm JE, Shadel GS, Churchill ME. Transcriptional activation by mitochondrial transcription factor A involves preferential distortion of promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:614–24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kukat C, Davies KM, Wurm CA, Spahr H, Bonekamp NA, Kuhl I, Joos F, Polosa PL, Park CB, Posse V, Falkenberg M, Jakobs S, Kuhlbrandt W, Larsson NG. Cross-strand binding of TFAM to a single mtDNA molecule forms the mitochondrial nucleoid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:11288–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512131112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaufman BA, Durisic N, Mativetsky JM, Costantino S, Hancock MA, Grutter P, Shoubridge EA. The mitochondrial transcription factor TFAM coordinates the assembly of multiple DNA molecules into nucleoid-like structures. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3225–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramachandran A, Basu U, Sultana S, Nandakumar D, Patel SS. Human mitochondrial transcription factors TFAM and TFB2M work synergistically in promoter melting during transcription initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:861–874. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Posse V, Gustafsson CM. Human Mitochondrial Transcription Factor B2 Is Required for Promoter Melting during Initiation of Transcription. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:2637–2645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.751008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hillen HS, Morozov YI, Sarfallah A, Temiakov D, Cramer P. Structural Basis of Mitochondrial Transcription Initiation. Cell. 2017;171:1072–1081 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morozov YI, Agaronyan K, Cheung AC, Anikin M, Cramer P, Temiakov D. A novel intermediate in transcription initiation by human mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:3884–93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morozov YI, Parshin AV, Agaronyan K, Cheung AC, Anikin M, Cramer P, Temiakov D. A model for transcription initiation in human mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:3726–35. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gustafsson CM, Falkenberg M, Larsson NG. Maintenance and Expression of Mammalian Mitochondrial DNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 2016;85:133–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shadel GS, Clayton DA. Mitochondrial DNA maintenance in vertebrates. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:409–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nicholls TJ, Minczuk M. In D-loop: 40 years of mitochondrial 7S DNA. Exp Gerontol. 2014;56:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang YE, Marinov GK, Wold BJ, Chan DC. Genome-wide analysis reveals coating of the mitochondrial genome by TFAM. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alam TI, Kanki T, Muta T, Ukaji K, Abe Y, Nakayama H, Takio K, Hamasaki N, Kang D. Human mitochondrial DNA is packaged with TFAM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1640–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takamatsu C, Umeda S, Ohsato T, Ohno T, Abe Y, Fukuoh A, Shinagawa H, Hamasaki N, Kang D. Regulation of mitochondrial D-loops by transcription factor A and single-stranded DNA-binding protein. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:451–6. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kanki T, Ohgaki K, Gaspari M, Gustafsson CM, Fukuoh A, Sasaki N, Hamasaki N, Kang D. Architectural role of mitochondrial transcription factor A in maintenance of human mitochondrial DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9823–34. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9823-9834.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsushima Y, Goto Y, Kaguni LS. Mitochondrial Lon protease regulates mitochondrial DNA copy number and transcription by selective degradation of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18410–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008924107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu B, Lee J, Nie X, Li M, Morozov YI, Venkatesh S, Bogenhagen DF, Temiakov D, Suzuki CK. Phosphorylation of human TFAM in mitochondria impairs DNA binding and promotes degradation by the AAA+ Lon protease. Mol Cell. 2013;49:121–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuhl I, Miranda M, Posse V, Milenkovic D, Mourier A, Siira SJ, Bonekamp NA, Neumann U, Filipovska A, Polosa PL, Gustafsson CM, Larsson NG. POLRMT regulates the switch between replication primer formation and gene expression of mammalian mtDNA. Sci Adv. 2016;2:e1600963. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Larsson NG, Wang J, Wilhelmsson H, Oldfors A, Rustin P, Lewandoski M, Barsh GS, Clayton DA. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and embryogenesis in mice. Nat Genet. 1998;18:231–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0398-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woo DK, Green PD, Santos JH, D’Souza AD, Walther Z, Martin WD, Christian BE, Chandel NS, Shadel GS. Mitochondrial Genome Instability and ROS Enhance Intestinal Tumorigenesis in APC(Min/+) Mice. The American Journal of Pathology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.West AP, Khoury-Hanold W, Staron M, Tal MC, Pineda CM, Lang SM, Bestwick M, Duguay BA, Raimundo N, MacDuff DA, Kaech SM, Smiley JR, Means RE, Iwasaki A, Shadel GS. Mitochondrial DNA stress primes the antiviral innate immune response. Nature. 2015;520:553–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ekstrand MI, Falkenberg M, Rantanen A, Park CB, Gaspari M, Hultenby K, Rustin P, Gustafsson CM, Larsson NG. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mtDNA copy number in mammals. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:935–44. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Campbell CT, Kolesar JE, Kaufman BA. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mitochondrial transcription initiation, DNA packaging, and genome copy number. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1819:921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pohjoismäki JLO, Wanrooij S, Hyvärinen AK, Goffart S, Holt IJ, Spelbrink JN, Jacobs HT. Alterations to the expression level of mitochondrial transcription factor A, TFAM, modify the mode of mitochondrial DNA replication in cultured human cells. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:5815–5828. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Farge G, Mehmedovic M, Baclayon M, van den Wildenberg SM, Roos WH, Gustafsson CM, Wuite GJ, Falkenberg M. In vitro-reconstituted nucleoids can block mitochondrial DNA replication and transcription. Cell Rep. 2014;8:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang KZ, Zhu J, Dagda RK, Uechi G, Cherra SJ, 3rd, Gusdon AM, Balasubramani M, Chu CT. ERK-mediated phosphorylation of TFAM downregulates mitochondrial transcription: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Mitochondrion. 2014;17:132–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suarez J, Hu Y, Makino A, Fricovsky E, Wang H, Dillmann WH. Alterations in mitochondrial function and cytosolic calcium induced by hyperglycemia are restored by mitochondrial transcription factor A in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1561–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00076.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dinardo MM, Musicco C, Fracasso F, Milella F, Gadaleta MN, Gadaleta G, Cantatore P. Acetylation and level of mitochondrial transcription factor A in several organs of young and old rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:187–91. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)03008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Santos JM, Mishra M, Kowluru RA. Posttranslational modification of mitochondrial transcription factor A in impaired mitochondria biogenesis: implications in diabetic retinopathy and metabolic memory phenomenon. Exp Eye Res. 2014;121:168–77. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andreeva L, Hiller B, Kostrewa D, Lassig C, de Oliveira Mann CC, Jan Drexler D, Maiser A, Gaidt M, Leonhardt H, Hornung V, Hopfner KP. cGAS senses long and HMGB/TFAM-bound U-turn DNA by forming protein-DNA ladders. Nature. 2017;549:394–398. doi: 10.1038/nature23890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.West AP, Shadel GS. Mitochondrial DNA in innate immune responses and inflammatory pathology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:363–375. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tuppen HA, Blakely EL, Turnbull DM, Taylor RW. Mitochondrial DNA mutations and human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:113–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Su B, Wang X, Zheng L, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Abnormal mitochondrial dynamics and neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bender A, Krishnan KJ, Morris CM, Taylor GA, Reeve AK, Perry RH, Jaros E, Hersheson JS, Betts J, Klopstock T, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. High levels of mitochondrial DNA deletions in substantia nigra neurons in aging and Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38:515–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Coskun P, Wyrembak J, Schriner SE, Chen HW, Marciniack C, Laferla F, Wallace DC. A mitochondrial etiology of Alzheimer and Parkinson disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:553–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ikebe S, Tanaka M, Ohno K, Sato W, Hattori K, Kondo T, Mizuno Y, Ozawa T. Increase of deleted mitochondrial DNA in the striatum in Parkinson’s disease and senescence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;170:1044–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90497-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kirches E. Do mtDNA Mutations Participate in the Pathogenesis of Sporadic Parkinson’s Disease? Curr Genomics. 2009;10:585–93. doi: 10.2174/138920209789503879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lin MT, Cantuti-Castelvetri I, Zheng K, Jackson KE, Tan YB, Arzberger T, Lees AJ, Betensky RA, Beal MF, Simon DK. Somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in early Parkinson and incidental Lewy body disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:850–4. doi: 10.1002/ana.23568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Coskun PE, Beal MF, Wallace DC. Alzheimer’s brains harbor somatic mtDNA control-region mutations that suppress mitochondrial transcription and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10726–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403649101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang J, Xiong S, Xie C, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Increased oxidative damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2005;93:953–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Coskun PE, Busciglio J. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Down’s Syndrome: Relevance to Aging and Dementia. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2012;2012:383170. doi: 10.1155/2012/383170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Coskun PE, Wyrembak J, Derbereva O, Melkonian G, Doran E, Lott IT, Head E, Cotman CW, Wallace DC. Systemic mitochondrial dysfunction and the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and down syndrome dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S293–310. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Phillips NR, Simpkins JW, Roby RK. Mitochondrial DNA deletions in Alzheimer’s brains: a review. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.04.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wei W, Keogh MJ, Wilson I, Coxhead J, Ryan S, Rollinson S, Griffin H, Kurzawa-Akanbi M, Santibanez-Koref M, Talbot K, Turner MR, McKenzie CA, Troakes C, Attems J, Smith C, Al Sarraj S, Morris CM, Ansorge O, Pickering-Brown S, Ironside JW, Chinnery PF. Mitochondrial DNA point mutations and relative copy number in 1363 disease and control human brains. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5:13. doi: 10.1186/s40478-016-0404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Keeney PM, Bennett JP., Jr ALS spinal neurons show varied and reduced mtDNA gene copy numbers and increased mtDNA gene deletions. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Andreu AL, Arbos MA, Perez-Martos A, Lopez-Perez MJ, Asin J, Lopez N, Montoya J, Schwartz S. Reduced mitochondrial DNA transcription in senescent rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:577–81. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sondheimer N, Glatz CE, Tirone JE, Deardorff MA, Krieger AM, Hakonarson H. Neutral mitochondrial heteroplasmy and the influence of aging. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1653–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gauthier BR, Wiederkehr A, Baquie M, Dai C, Powers AC, Kerr-Conte J, Pattou F, MacDonald RJ, Ferrer J, Wollheim CB. PDX1 deficiency causes mitochondrial dysfunction and defective insulin secretion through TFAM suppression. Cell Metab. 2009;10:110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ikeuchi M, Matsusaka H, Kang D, Matsushima S, Ide T, Kubota T, Fujiwara T, Hamasaki N, Takeshita A, Sunagawa K, Tsutsui H. Overexpression of mitochondrial transcription factor a ameliorates mitochondrial deficiencies and cardiac failure after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;112:683–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ikeda M, Ide T, Fujino T, Arai S, Saku K, Kakino T, Tyynismaa H, Yamasaki T, Yamada K, Kang D, Suomalainen A, Sunagawa K. Overexpression of TFAM or twinkle increases mtDNA copy number and facilitates cardioprotection associated with limited mitochondrial oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhong Y, Hu YJ, Chen B, Peng W, Sun Y, Yang Y, Zhao XY, Fan GR, Huang X, Kong WJ. Mitochondrial transcription factor A overexpression and base excision repair deficiency in the inner ear of rats with D-galactose-induced aging. FEBS J. 2011;278:2500–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hayashi Y, Yoshida M, Yamato M, Ide T, Wu Z, Ochi-Shindou M, Kanki T, Kang D, Sunagawa K, Tsutsui H, Nakanishi H. Reverse of age-dependent memory impairment and mitochondrial DNA damage in microglia by an overexpression of human mitochondrial transcription factor a in mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8624–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1957-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Morimoto N, Miyazaki K, Kurata T, Ikeda Y, Matsuura T, Kang D, Ide T, Abe K. Effect of mitochondrial transcription factor a overexpression on motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model mice. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:1200–8. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xu S, Zhong M, Zhang L, Wang Y, Zhou Z, Hao Y, Zhang W, Yang X, Wei A, Pei L, Yu Z. Overexpression of Tfam protects mitochondria against beta-amyloid-induced oxidative damage in SH-SY5Y cells. FEBS J. 2009;276:3800–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Oka S, Leon J, Sakumi K, Ide T, Kang D, LaFerla FM, Nakabeppu Y. Human mitochondrial transcriptional factor A breaks the mitochondria-mediated vicious cycle in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37889. doi: 10.1038/srep37889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim J, Moody JP, Edgerly CK, Bordiuk OL, Cormier K, Smith K, Beal MF, Ferrante RJ. Mitochondrial loss, dysfunction and altered dynamics in Huntington’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3919–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rice AC, Keeney PM, Algarzae NK, Ladd AC, Thomas RR, Bennett JP., Jr Mitochondrial DNA copy numbers in pyramidal neurons are decreased and mitochondrial biogenesis transcriptome signaling is disrupted in Alzheimer’s disease hippocampi. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:319–30. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Grunewald A, Rygiel KA, Hepplewhite PD, Morris CM, Picard M, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial DNA Depletion in Respiratory Chain-Deficient Parkinson Disease Neurons. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:366–78. doi: 10.1002/ana.24571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ross CA. Intranuclear neuronal inclusions: a common pathogenic mechanism for glutamine-repeat neurodegenerative diseases? Neuron. 1997;19:1147–50. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mangiarini L, Sathasivam K, Seller M, Cozens B, Harper A, Hetherington C, Lawton M, Trottier Y, Lehrach H, Davies SW, Bates GP. Exon 1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell. 1996;87:493–506. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Acevedo-Torres K, Berrios L, Rosario N, Dufault V, Skatchkov S, Eaton MJ, Torres-Ramos CA, Ayala-Torres S. Mitochondrial DNA damage is a hallmark of chemically induced and the R6/2 transgenic model of Huntington’s disease. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:126–36. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]