Abstract

Kensinger (in press) and Mather (2007) both argue that intrinsic features of emotional items are remembered better than intrinsic features of non-emotional items. However, Kensinger attributes these effects to negative valence whereas Mather attributes them to arousal. In this paper, we note several reasons why arousal may be the driving factor even when a study reveals more detailed memory for negative items than for positive items. We also reanalyze previous data (Mather & Nesmith, 2008) to show that although both arousal and negative valence were correlated with memory accuracy, enhanced memory accuracy was accounted for by arousal rather than valence.

Kensinger (in press) argues that positive emotions lead to more schematic memories whereas negative emotions lead to more accurate memory for event details. Specifically, Kensinger argues that intrinsic attributes of negative stimuli are better remembered than extrinsic information because during the initial experience, people focus on negative information to the detriment of other event details. This creates tradeoffs in memory when there is an object that grabs attention.

Kensinger’s perspective is broadly consistent with an object-based framework proposed to explain how emotional arousal can enhance or impair memory binding (Mather, 2007). The object-based framework posits that arousal evoked by an object is the source of enhanced memory for emotional objects and their intrinsic features. “Arousal” describes heightened physiological activity. Feelings of excitement, nervousness or alertness characterize high arousal states while feelings of relaxation or boredom characterize low arousal states. Enhanced within-object memory binding for emotionally arousing objects occurs because: 1) arousing objects attract focused attention; 2) focused attention is required for initial perceptual binding; and 3) emotionally arousing items have privileged access to working memory, where initial perceptual binding can be maintained and consolidated into long-term memory. In contrast, no initial perceptual binding benefits occur for contextual details that are not intrinsic to the arousing object.

A key distinction between the object-based framework and Kensinger’s proposal is the focus on negative valence versus arousal. Kensinger (in press) argues that memory enhancements for intrinsic details of emotional objects only occur for negative items, whereas Mather (2007) attributes the effects to arousal rather than to valence. Arousal may be the underlying mechanism even when a study reveals more detailed memory for negative items than positive items, as negative valence tends to be more strongly correlated with arousal than positive valence, particularly for women (Bradley et al., 2001). Furthermore, equating arousal ratings for two sets of stimuli does not necessarily equate the physiological arousal they evoke (Bradley et al., 2008; Hamann et al., 2004).

Studies comparing the likelihood of reporting vivid memory for words or pictures (Dewhurst & Parry, 2000; Ochsner, 2000) found that negative items were more likely than neutral items to be remembered vividly. A smaller memory enhancement was also seen for positive items. Moreover, studies examining memory for the color or location of positive and negative words revealed that features of emotional words were better remembered than features of neutral words (D'Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004; Doerksen & Shimamura, 2001). Thus, positive items may show similar but less pronounced within-object memory enhancements as negative items – a pattern more consistent with an arousal mechanism than with a negative valence mechanism, which predicts no memory enhancement for intrinsic details of positive items.

In contrast, subjects shown a series of neutral and emotional objects (such as airplanes and snakes) could more accurately distinguish previously viewed negative objects from similar foils, whereas no memory advantage was observed for details of positive objects (Kensinger et al., 2007). Given the weaker association of positive valence and arousal than negative valence and arousal, especially for women (most of the participants were female), it is unclear whether the lack of memory enhancement for intrinsic details of positive objects stems from the absence of negative valence or lower levels of arousal.

A recent study suggests that equating the visual and semantic content of arousing and neutral items can reveal arousal effects for positive stimuli that otherwise would go undetected (Mather & Nesmith, 2008, Experiment 1). This study used 72 pairs of pictures. Each pair had pictures with different arousal levels but a similar appearance. For instance, a picture of a man with a gun to his head was paired with a picture of a man with a hairdryer to his head. Arousing and non-arousing versions of each picture pair were counterbalanced across participants. Participants viewed a slide show of the pictures in various locations and then took a picture-location memory test.

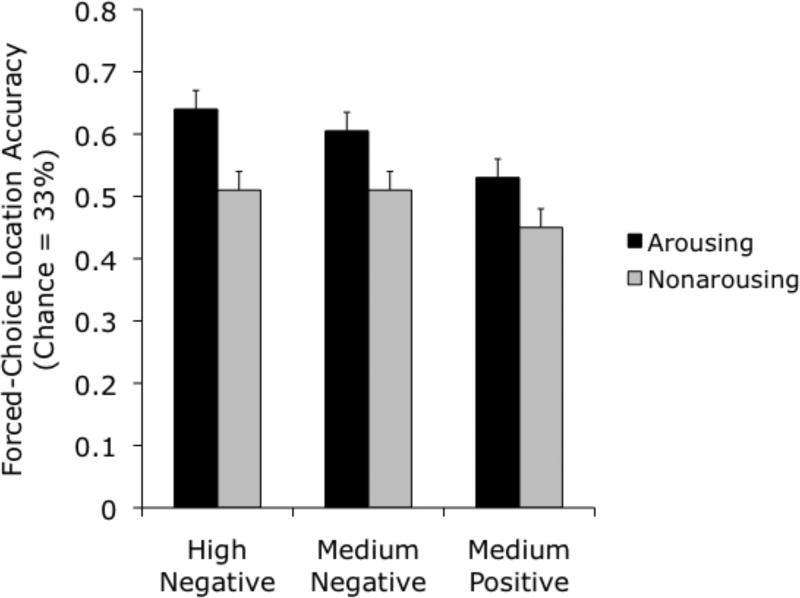

As shown in Figure 1, location memory was better for arousing pictures than for non-arousing pictures, regardless of valence. However, overall location memory was worse for positive pictures and their non-arousing matches than for negative pictures and their non-arousing matches. Thus, an un-yoked design comparing positive and negative pictures to an overall pool of neutral pictures might not have revealed memory enhancement for positive pictures. This suggests that non-emotional aspects of negative pictures contribute to the vivid memories they evoke. Controlling for these non-emotional aspects enables a more accurate investigation of how arousal impacts memory for negative and positive pictures.

Figure 1.

Location memory performance for arousing and non-arousing pictures in Experiment 1 of Mather and Nesmith’s (2008) study (averaged across the lag and no-lag conditions) reveals that positive arousing pictures were remembered better than their matched non-arousing pictures, even though location accuracy was near the levels seen for the non-arousing matches for high and medium arousal negative pictures.

To glean more information from these data, we conducted item analyses by correlating average arousal and valence ratings for each picture with its average location accuracy. Table 1 shows that both arousal and valence ratings correlated with location accuracy, although arousal did so more reliably. Across the board, arousal and valence ratings were highly correlated. Thus, to test whether arousal and valence each make independent contributions to memory for detail, we conducted partial correlations. The correlation between arousal and location accuracy remained significant when controlling for valence, r(141) = .26, p<.01, yet the correlation between valence and location accuracy was not significant when controlling for arousal, r(141) = .02, p>.8.

Table 1.

Correlations (r) between picture ratings and location accuracy in Experiments 1–3 of Mather and Nesmith (2008).

| Valence-Accuracy Correlation |

Arousal-Accuracy Correlation |

Valence-Arousal Correlation |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 – all 144 items | −.19* | .21* | −.69** |

| Experiment 2 – all 144 items | −.29** | .36** | −.76** |

| Experiment 3 – all 144 items | −.08 | .25** | −.62** |

| Negative high arousal set1 | −.35* | .34* | −.92** |

| Negative medium arousal set1 | −.24 | .31* | −.84** |

| Positive medium arousal set1 | .17 | .45** | .59** |

p<.05;

p<.01.

Average ratings across the three experiments were used, and matched non-arousing pictures from the set were included, yielding 48 pictures for each correlation.

Although certain studies implicate negative valence in enhanced memory for emotional information, these studies fail to rule out and in some instances support arousal as the critical factor underlying enhanced memory for intrinsic details of emotional objects. Yoked designs afford more accurate comparisons across visual stimuli, and may reveal effects that may otherwise remain undetected. The use of such designs should be encouraged. In any case, further research is needed to better characterize the related versus independent contributions of arousal and valence to memory accuracy.

References

- Bradley MM, Codispoti M, Sabatinelli D, Lang PJ. Emotion and motivation II: Sex differences in picture processing. Emotion. 2001;1:300–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Miccoli L, Escrig MA, Lang PJ. The pupil as a measure of emotional arousal and autonomic activation. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:602–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Argembeau A, Van der Linden M. Influence of affective meaning on memory for contextual information. Emotion. 2004;4:173–188. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.4.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhurst SA, Parry LA. Emotionality, distinctiveness, and recollective experience. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 2000;12:541–551. [Google Scholar]

- Doerksen S, Shimamura AP. Source memory enhancement for emotional words. Emotion. 2001;1:5–11. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S, Herman RA, Nolan CL, Wallen K. Men and women differ in amygdala response to visual sexual stimuli. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:411–416. doi: 10.1038/nn1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA. Remembering the details: Effects of emotion. Emotion Review. doi: 10.1177/1754073908100432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Garoff-Eaton RJ, Schacter DL. Effects of emotion on memory specificity in young and older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2007;62:208–215. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.p208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M. Emotional arousal and memory binding: An object-based framework. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2:33–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Nesmith K. Arousal-enhanced location memory for pictures. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;58:449–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN. Are affective events richly recollected or simply familiar? The experience and process of recognizing feelings past. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2000;129:242–261. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.129.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]