To the Editor

[18F]-fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol ([18F]-FEOBV) is a vesamicol analogue selectively binding the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT), a protein expressed uniquely by cholinergic neurons1. Non-invasive and short duration PET imaging acquisition protocols allowing accurate quantification of VAChT are preferred in patients with dementia because of their limited ability to lay still during prolonged imaging sessions. Recently, Aghourian et al. reported in vivo quantification of brain cholinergic denervation in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) using simplified and non-invasive [18F]-FEOBV PET imaging2. These authors applied an abbreviated and non-invasive 30-minute imaging protocol with white matter as a reference region to estimate regional gray matter VAChT binding. The white matter reference region was chosen based on non-specific binding patterns of time-activity curves during late uptake (3–3.5 hours) scan phases. This approach departs from previously used cerebellar gray matter reference regions3. This is appropriate as the cerebellar cortex contains cholinergic nerve terminals resulting in specific VAChT uptake4. Furthermore, cholinergic terminal changes may occur in cerebellar cortices in neurodegenerative disorders, potentially further invalidating the use of this reference region5. Using the white matter reference region method, Aghourian et al. reported evidence of prominent cortical VAChT losses in AD patients with the greatest reductions observed in the temporal cortex2. No significant differences were found in the hippocampus or subcortical regions between AD patients and age-matched normal control subjects. These observations indicate that septal nuclei and the substantia innominata, the proposed origins of the cholinergic projections to the hippocampus and neocortex, respectively, are differentially involved in AD.

We determined the feasibility of using a similar non-invasive and abbreviated [18F]-FEOBV brain PET imaging protocol in a different dementia population (dementia with Lewy bodies, DLB) and to assess the non-specificity of white matter reference region binding. We hypothesized that radiotracer uptake in a supratentorial white matter reference region is also non-specific in DLB, allowing the quantification of gray matter VAChT reductions in this α-synucleinopathy.

Our study sample consisted of 18 participants, including four subjects diagnosed with DLB (2 females; mean age 76.0±1.4 years, duration of disease 4.2±2.2 years and Mini-Mental Status Examination, 17.8±5.1) and 14 normal control elderly (7 females; mean age 75.1±5.3 years). The patients in the present study were diagnosed as having probable DLB using the third international clinical diagnostic consensus criteria6. All patients were recruited at the Cognitive Disorders Clinic at the University of Michigan Health System. The 14 normal control subjects were identified through our existing normal control elderly database covering the age range and gender distribution of the patients. The normal control subjects did not have a history of neurological or psychiatric disease and had a normal neurological examination at the time of PET imaging. Subjects with evidence of large vessel stroke or other intracranial lesions were excluded. All studies were conducted in accordance with the University of Michigan Medical School IRB approved protocol. All subjects provided written informed consent before study participation.

All subjects underwent brain MRI and VAChT [18F]-FEOBV PET imaging. T1-weighted MRI was performed on a 3 Tesla Philips Achieva system (Philips, Best, The Netherlands). A 3D inversion recovery-prepared turbo-field-echo was performed in the sagittal plane using TR/TE/TI=9.8/4.6/1041ms; turbo factor=200; single average; FOV=240×200×160mm; acquired Matrix = 240×200×160slices and reconstructed to 1mm isotropic resolution. PET imaging was performed in 3D imaging mode with an ECAT Exact HR+ tomograph (Siemens Molecular Imaging, Inc., Knoxville, TN) as previously reported7. [18F]-FEOBV was prepared in high radiochemical purity (>95%)8. Delayed dynamic imaging was performed over 30 minutes (in six 5-minute frames) starting 3 hours after an intravenous bolus dose injection of 8 mCi [18F]-FEOBV3. The PET imaging frames were spatially coregistered within subjects with a rigid-body transformation to reduce the effects of subject motion during the imaging session9. Neurostat software (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) was used for PET-MRI registration using the cropped T1-weighted MR volumetric scan.

Freesurfer software (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) was used to define cortical and subcortical MR gray volumes-of-interest (VOI). Supratentorial white matter segments were isolated using Freesurfer software to create a white matter mask. These WM masks were eroded using a morphological filter to include only the core voxels of the supratentorial WM to minimize the partial volume effects of the cortical areas. Given the proximity of the WM voxels to high binding subcortical regions below the lateral ventricles (such as the striatum and thalamus) only WM voxels above the ventricles were included in the measurements. Time-activity curves for the 3–3.5 hours delayed PET imaging protocol (defined for the global cortex, thalamus and white matter) were compared to assess for absence or presence of overlap between the two groups for which purpose the sample size was sufficient. Distribution volume ratios (DVR) were calculated from ratio of total volume of distribution estimates for gray matter target and white matter reference tissues3. Late static imaging studies will yield DVR values nearly identical to standardized uptake value ratios (SUVr) binding values; DVR values obtained in our study are comparable to SUVr values used in the study by Aghourian et al.2.

Early post-injection imaging data were also available for the DLB patients and a small subset of the normal control subjects. The early (first 4 minutes) post-injection images were used to compute K1 flow delivery images. K1 flow delivery images are highly correlated with cerebral blood flow and can be used as a proxy for regional cerebral blood flow or glucose metabolism10. These images were used to compare the regional topography of flow changes to the pattern of VAChT binding. K1 flow delivery images were normalized to the cerebellar hemisphere (K1R), a stable blood flow and metabolic region, as global normalization may attenuate disease-specific blood flow patterns.

Standard pooled-variance t-test or Satterthwaite’s method of approximate t-test (tapprox) were used for statistical group comparisons (SAS version 9.3, SAS institute, Cary, North Carolina). Statistical inferences were made on meeting two-tailed testing requirement for α<0.05 and Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Our findings showed that average time-activity curve activities in the segmented white matter between the DLB patients and the elderly normal controls were nearly identical, i.e., mean white matter concentrations scaled to injected dose were within 1% of each other (Figure 1). Time-activity curves for the thalamus and cortex show substantially lower activity values for DLB patients compared to control subjects.

Figure 1.

Time-activity curves for the delayed PET scan acquisition showing near identical white matter curves for the dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and elderly normal control (NC) groups. Time-activity curves for the thalamus and cortex show substantially lower activity values for the dementia patients compared to the control subjects.

There were diffuse neocortical VAChT binding losses (frontal −16.8%, P<0.0001; temporal −25.7%, P<0.0001; parietal −19.5%, P<0.0001 and occipital cortex −17.7%, P<0.0001) in DLB subjects compared to control subjects (Table 1, Figure 2). We also observed significant reductions in limbic (hippocampus: −19.8%, P<0.0001; amygdala: −17.5%, P=0.0001) structures and the thalamus (−20.6%, P=0.0011) in our DLB subjects.

Table 1.

Mean (± SD) values of regional cerebral [18F]FEOBV VAChT distribution volume ratios (DVR) in the patients with DLB and normal control elderly. Levels of statistical difference between groups are presented.

| VAChT DVR | DLB (n =4) | Elderly control (n=14) |

Group comparison (significance) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global neocortex | 0.98±0.04 | 1.23±0.06 | −20.3%, t=−7.4, P<0.0001 |

| Frontal cortex | 1.09±0.06 | 1.31±0.07 | −16.8%, t=−6.0, P<0.0001 |

| Temporal cortex | 1.04±0.08 | 1.40±0.09 | −25.7%, t=−7.5, P<0.0001 |

| Parietal cortex | 0.95±0.03 | 1.18±0.07 | −19.5%, t=−6.4, P<0.0001 |

| Occipital cortex | 0.84±0.06 | 1.02±0.08 | −17.7%, t=−4.0, P=0.001 |

| Hippocampus | 1.5±0.06 | 1.87±0.21 | −19.8%, tapprox =−5.5, P<0.0001 |

| Amygdala | 1.88±0.06 | 2.28±0.27 | −17.5%, tapprox =−5.2, P=0.0001 |

| Thalamus | 1.66±0.12 | 2.09±0.32 | −20.6%, tapprox =−4.1, P=0.0011 |

Abbreviations: DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; VAChT, vesicular acetylcholine transporter.

tapprox= Satterthwaite’s method of approximate t tests.

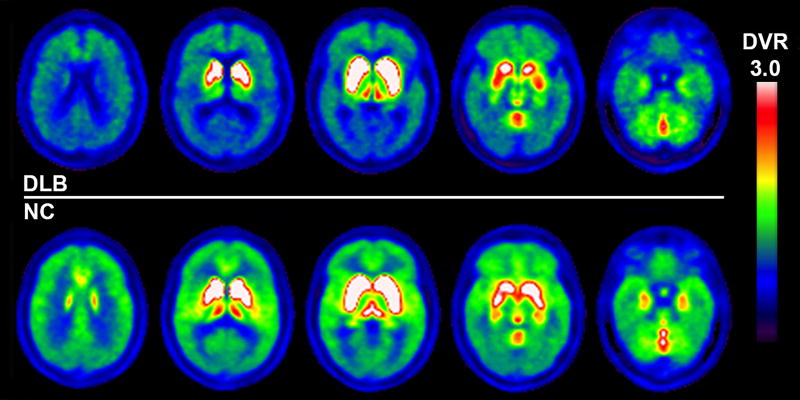

Figure 2.

Vesicular acetylcholine transporter [18F]FEOBV PET images show significantly reduced vesicular acetylcholine transporter activity in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (upper row) compared to findings from representative elderly control subjects (lower row). Reductions are present not only in extensive cortical but also in limbic and sub-cortical regions, such as the thalami.

It is possible that DLB disease-specific regional cerebral blood flow changes might affect VAChT binding estimates based on the use of the supratentorial white matter as a reference region. Therefore, we compared the topography of [18F]-FEOBV DVR binding images to the patterns of disease-specific flow changes in [18F]-FEOBV K1 images. K1 measures blood to brain tracer delivery and reflects regional cerebral blood flow. The K1 flow delivery images showed regionally prominent parieto-temporal, occipital, and posterior cingulate neocortical reductions with relative sparing of frontal cortices (Figure 3). Direct comparison of [18F]-FEOBV DVR binding Figure 2) and the K1 flow delivery images (Figure 3) showed more diffuse neocortical [18F]-FEOBV DVR reductions and prominent [18F]-FEOBV binding in the hippocampi, basal ganglia, thalami, cerebellar vermis and dorsal pontomesencephalic brainstem regions compared to the flow images.

Figure 3.

K1 flow delivery images (normalized to the cerebellum K1R) show prominent parieto-temporal, occipital and posterior cingulate cortical reductions in the patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB, upper row) compared to findings from representative elderly control subjects (lower row). Frontal flow was relatively spared in the DLB patients.

We agree with Aghourian et al., that the use of the supratentorial white matter reference region is feasible for the non-invasive quantification of brain cholinergic transporter changes using delayed imaging acquisition of [18F]-FEOBV PET in subjects with dementia. Immunochemistry studies have not shown significant levels of VAChT in white matter11, 12, making the white matter as a suitable candidate reference region for brain PET VAChT quantification. In the present [18F]-FEOBV PET study, time-activity curves for the delayed PET scan acquisition showed near identical white matter curves for the DLB and elderly normal control groups. Mean white matter radiotracer concentrations scaled to injected dose for the patient and control groups were within 1% of each other. These findings confirm previous observations that white matter [18F]-FEOBV radioligand binding is consistent with non-specific binding as shown in AD2.

It is possible that disease-specific regional cerebral blood flow changes in DLB may affect VAChT binding estimates based on the use of the white matter as a reference region. Comparison, however, between K1 flow delivery and late DVR binding images demonstrated significant regional differences. Our K1 flow delivery images parallel known [18F]-FDG glucose metabolic or regional cerebral blood flow abnormalities in DLB, in particular, prominent parieto-temporal, occipital and posterior cingulate cortical reductions13. In contrast, [18F]-FEOBV DVR binding images show more diffuse neocortical reductions but with prominent binding in the hippocampi, basal ganglia, thalami, cerebellar vermis, and dorsal pontomesencephalic brainstem regions. We previously reported computer simulations using full dynamic modeling of [18F]-FEOBV data obtained in young normal subjects3. These simulations show that decreases in cerebral blood flow of 20% in the striatum would result in only a 3.5% reduction in the striatal binding values of delayed [18F]-FEOBV binding. Predicted flow-related bias was even smaller in regions with lower VAChT density, where isolated 20% flow reductions in the thalamus and occipital cortex would result in late binding discrepancies of only −0.6% and +0.1%, respectively3. These findings support the utility of delayed [18F]-FEOBV DVR binding data (using supratentorial white matter as a reference region) to reliably estimate VAChT binding without significant bias from blood flow changes. Due to possible ageing effects on white matter integrity, caution may be needed in using white matter as a reference region when comparing groups of different ages. We found, however, similar results in younger subjects14. Further studies are also needed to validate this method in the setting of vascular disease affecting white matter integrity.

Cholinergic neurons of the forebrain are grouped according to the efferent projection targets: the Ch1 (medial septal nucleus) and the Ch2 (vertical limb nucleus of the diagonal band of Broca) project to hippocampus; the Ch4 group (encompassing the nucleus basalis of Meynert) projects to the neocortical mantle and amygdala15. The Ch5 (pedunculopontine nucleus and Ch6 (laterodorsal tegmental complex) groups project to the thalamus, basal ganglia, basal forebrain, other brainstem structures, and spinal cord16, 17. The striatum also contains intrinsic cholinergic interneurons with a remarkably high density of cholinergic terminals18, 19. Aghourian and colleagues reported evidence of prominent neocortical VAChT losses in AD patients with greatest reductions observed in temporal cortex2. No significant differences were found in the hippocampus or subcortical regions between AD patients and age-matched normal control subjects. These observations indicate predominant involvement of the Ch4 group with sparing of the Ch1-2 and Ch5-6 cholinergic cell groups in AD. Using a similar PET delayed imaging acquisition and image analysis protocol as Aghourian et al., we also found diffuse neocortical losses in the DLB subjects compared to normal elderly controls with greatest magnitude reductions in temporal cortex. In addition, we observed significant reductions in hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus in our DLB subjects. Our data suggest more extensive degeneration of cholinergic cell groups in the basal forebrain in DLB than in AD, including involvement of mesopontine Ch5-6 neurons. Extensive cortical and subcortical cholinergic nerve terminal losses were also demonstrated in a recent VAChT [123I]IBVM SPECT study in DLB20. Estimates of cholinergic terminal losses were higher than observed in this study, which may be due to technical factors or clinical differences between study populations. One of these technical factors may be the use of cerebellar hemisphere reference regions where cholinergic nerve terminals may be altered by disease processes, possibly resulting in overestimation of group differences5.

These preliminary VAChT imaging studies in DLB and AD suggest that not only thalamic but also limbic (hippocampal and amygdala) reductions seen in DLB may be used for the differential diagnosis between these two common dementia syndromes. We previously compared thalamic acetylcholinesteras hydrolysis rates using [11C]-methyl-4-piperidinyl propionate (PMP) PET imaging in patients with AD, DLB, PD dementia and PD21. Compared to normal control subjects, reduced thalamic hydrolysis was noted in subjects with PDD (−19.8%), DLB (−17.4%) and PD (−12.8%). Each of these 3 subgroups was statistically different from AD subjects (−0.7%) who showed relatively spared thalamic hydrolysis rates which were comparable to normal elderly. These in vivo imaging data agree with previous post-mortem studies showing that there is selective loss of basal forebrain neurons in AD, with relative sparing of the brainstem pedunculopontine cholinergic neurons22, 23, 24. Thalamic cholinergic denervation may partly explain the greater frequency of falls and parasomnias in DLB compared to AD25, 26. It should be noted however that young-onset AD (age 64 or younger) may be associated with significant thalamic and also hippocampal cholinergic reductions as shown in a prior VAChT [123I]IBVM SPECT study27. Another [123I]IBVM SPECT study found VAChT reductions in the bilateral perihippocampal-amygdaloid complexes in elderly with AD28.

A limitation of the our study is the small sample size. Larger future studies are needed to not only confirm our initial observations but also compare the differential diagnostic accuracy of [18F]FEOBV PET to other imaging approaches that are used to distinguish DLB from AD. These comparison approaches include [18F]Fluorodexoglucose (FDG) PET and [123I]Ioflupane dopamine transporter SPECT imaging29, 30. In this respect, [18F]FEOBV PET may have potential advantages as both FDG PET (limited sensitivity of occipital lobe hypometabolism as a marker of DLB) and dopamine transporter imaging (limited specificity as this technique will also be abnormal in atypical parkinsonian syndromes presenting with dementia, such as progressive supranuclear palsy) have drawbacks10, 13, 31.

We conclude that the use of supratentorial white matter reference regions is feasible for non-invasive quantification of brain VAChT changes using delayed imaging acquisition of [18F]-FEOBV PET in subjects with dementia. Unlike AD, VAChT reductions are more extensive and affect neocortical, limbic, and thalamic regions in DLB.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by NIH grants P01 NS015655, RO1 NS070856, P50 NS091856 and R21 NS088302. We are indebted to the subjects who participated in this study.

Robert Koeppe has received grant support from the NIH. Roger Albin has received grant support from the NIH and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Kirk Frey has received research support from the NIH, GE Healthcare and AVID Radiopharmaceuticals (Eli Lilly subsidiary). Martijn Muller has received research support from the NIH, Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Department of Veteran Affairs and Axovant Sciences. Nicolaas Bohnen has received research support from the NIH, Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Department of Veteran Affairs and Axovant Sciences. Dr. Nejad-Davarani reports no sources of funding.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no relevant biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

SND and NIB were responsible for drafting the text and statistical analysis.

RAK was responsible for the time-activity activity curve analysis, kinetic analysis and drafting of figures.

KAF was responsible for conception and design of the study

KAF, RLA, MLTMM and NIB were responsible for acquisition of data.

References

- 1.Kilbourn MR, Hockley B, Lee L, Sherman P, Quesada C, Frey KA, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of (2R,3R)-5-[(18)F]fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol in rat and monkey brain: a radioligand for the vesicular acetylcholine transporter. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36(5):489–493. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aghourian M, Legault-Denis C, Soucy JP, Rosa-Neto P, Gauthier S, Kostikov A, et al. Quantification of brain cholinergic denervation in Alzheimer's disease using PET imaging with [18F]-FEOBV. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(11):1531–1538. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrou M, Frey KA, Kilbourn MR, Scott PJ, Raffel DM, Bohnen NI, et al. In vivo imaging of human cholinergic nerve terminals with (−)-5-(18)F-fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol: biodistribution, dosimetry, and tracer kinetic analyses. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(3):396–404. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.124792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schafer MK, Eiden LE, Weihe E. Cholinergic neurons and terminal fields revealed by immunohistochemistry for the vesicular acetylcholine transporter. I. Central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1998;84(2):331–359. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00516-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilman S, Koeppe RA, Nan B, Wang CN, Wang X, Junck L, et al. Cerebral cortical and subcortical cholinergic deficits in parkinsonian syndromes. Neurology. 2010;74(18):1416–1423. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dc1a55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohnen NI, Muller MLTM, Kotagal V, Koeppe RA, Kilbourn MR, Gilman S, et al. Heterogeneity of cholinergic denervation in Parkinson's disease without dementia. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2012;32(8):1609–1617. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shao X, Hoareau R, Hockley BG, Tluczek LJ, Henderson BD, Padgett HC, et al. Highlighting the Versatility of the Tracerlab Synthesis Modules. Part 1: Fully Automated Production of [18F]Labelled Radiopharmaceuticals using a Tracerlab FXFN. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2011;54(6):292–307. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minoshima S, Koeppe RA, Fessler JA, Mintun MA, Berger KL, Taylor SF, et al. Integrated and automated data analysis method for neuronal activation studying using O15 wate PET. In: Uemura K, Lassen NA, Jones T, Kanno I, editors. Quantification of brain function to tracer kinetics and image analysis in brain PET; International Congress Series 1030. Excerpta Medica; Tokyo. 1993. pp. 409–418. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koeppe RA, Gilman S, Joshi A, Liu S, Little R, Junck L, et al. 11C-DTBZ and 18F-FDG PET measures in differentiating dementias. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(6):936–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilmor ML, Nash NR, Roghani A, Edwards RH, Yi H, Hersch SM, et al. Expression of the putative vesicular acetylcholine transporter in rat brain and localization in cholinergic synaptic vesicles. J Neurosci. 1996;16(7):2179–2190. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02179.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arvidsson U, Riedl M, Elde R, Meister B. Vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) protein: a novel and unique marker for cholinergic neurons in the central and peripheral nervous systems. J Comp Neurol. 1997;378(4):454–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minoshima S, Foster NL, Sima AA, Frey KA, Albin RL, Kuhl DE. Alzheimer's disease versus dementia with Lewy bodies: cerebral metabolic distinction with autopsy confirmation. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:358–365. doi: 10.1002/ana.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albin RL, Minderovic C, Koeppe RA. Normal Striatal Vesicular Acetylcholine Transporter Expression in Tourette Syndrome. Eneuro. 2017;4(4) doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0178-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesulam M, Mufson E, Levy A, Wainer B. Cholinergic innervation of cortex by the basal forebrain: Cytochemistry and cortical connections of the septal area, diagonal band nuclei, nucleus basalis (substantia innominata), and hypothalamus in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1983;214:170–197. doi: 10.1002/cne.902140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Wainer BH, Levy AI. Central cholinergic pathways in the rat: An overview based on an alternative nomenclature (CH1-CH-6) Neurosci. 1983;10:1185–1201. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heckers S, Geula C, Mesulam M. Cholinergic innervation of the human thalamus: Dual origin and differential nuclear distribution. J Comp Neurol. 1992;325:68–82. doi: 10.1002/cne.903250107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fibiger H. The organization and some projections of cholinergic neurons of the mammalian forebrain. Brain Res Rev. 1982;4:327–388. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(82)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mesulam M, Mash D, Hersh L, Bothwell M, Geula C. Cholinergic innervation of the human striatum, globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, substantia nigra, and red nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1992;323:252–268. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazere J, Lamare F, Allard M, Fernandez P, Mayo W. 123I-Iodobenzovesamicol SPECT Imaging of Cholinergic Systems in Dementia with Lewy Bodies. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(1):123–128. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.176180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotagal V, Muller ML, Kaufer DI, Koeppe RA, Bohnen NI. Thalamic cholinergic innervation is spared in Alzheimer disease compared to parkinsonian disorders. Neurosci Lett. 2012;514(2):169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.02.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolf NJ, Jacobs RW, Butcher LL. The pontomesencephalotegmental cholinergic system does not degenerate in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 1989;96(3):277–282. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandel JP, Hirsch EC, Malessa S, Duyckaerts C, Cervera P, Agid Y. Differential vulnerability of cholinergic projections to the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus in senile dementia of Alzheimer type and progressive supranuclear palsy. Neuroscience. 1991;41(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90197-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dugger BN, Murray ME, Boeve BF, Parisi JE, Benarroch EE, Ferman TJ, et al. Neuropathological analysis of brainstem cholinergic and catecholaminergic nuclei in relation to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2012;38(2):142–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohnen NI, Muller ML, Koeppe RA, Studenski SA, Kilbourn MA, Frey KA, et al. History of falls in Parkinson disease is associated with reduced cholinergic activity. Neurology. 2009;73(20):1670–1676. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c1ded6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotagal V, Albin RL, Muller MLTM, Koeppe RA, Chervin RD, Frey KA, et al. Symptoms of Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder are associated with Cholinergic Denervation in Parkinson Disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(4):560–568. doi: 10.1002/ana.22691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuhl D, Minoshima S, Fessler J, Frey K, Foster N, Ficaro E, et al. In vivo mapping of cholinergic terminals in normal aging, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:399–410. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazere J, Prunier C, Barret O, Guyot M, Hommet C, Guilloteau D, et al. In vivo SPECT imaging of vesicular acetylcholine transporter using [(123)I]-IBVM in early Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 2008;40(1):280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bohnen NI, Djang DS, Herholz K, Anzai Y, Minoshima S. Effectiveness and safety of 18F-FDG PET in the evaluation of dementia: a review of the recent literature. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(1):59–71. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.096578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker Z, Costa DC, Walker RW, Shaw K, Gacinovic S, Stevens T, et al. Differentiation of dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer's disease using a dopaminergic presynaptic ligand. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:134–140. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall V, Grosset D. Role of dopamine transporter imaging in routine clinical practice. Mov Disord. 2003;18(12):1415–1423. doi: 10.1002/mds.10592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]