Abstract

Anti–N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis is the most common autoimmune encephalitis related to autoantibody‐mediated synaptic dysfunction. Cerebrospinal fluid–derived human monoclonal NR1 autoantibodies showed low numbers of somatic hypermutations or were unmutated. These unexpected germline‐configured antibodies showed weaker binding to the NMDAR than matured antibodies from the same patient. In primary hippocampal neurons, germline NR1 autoantibodies strongly and specifically reduced total and synaptic NMDAR currents in a dose‐ and time‐dependent manner. The findings suggest that functional NMDAR antibodies are part of the human naïve B cell repertoire. Given their effects on synaptic function, they might contribute to a broad spectrum of neuropsychiatric symptoms. Ann Neurol 2019;85:771–776

Autoantibodies against the aminoterminal domain (ATD) of the NR1 subunit of the N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (NMDA) receptor (NMDAR) are the hallmark of NMDAR encephalitis, the most common autoimmune encephalitis presenting with psychosis, epileptic seizures, amnesia, and autonomic instability.1 The disease can be triggered by NMDAR‐expressing teratomas2 and occur secondarily to viral encephalitis;3, 4 however, in most cases, the initiating events remain unclear. Intracerebroventricular injection of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), as well as a single recombinant monoclonal NR1 immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody obtained from clonally expanded intrathecal plasma cells of a patient with NMDAR encephalitis into mice, led to transient behavioral changes compatible with human disease symptoms.5, 6

We could recently generate a panel of human monoclonal NMDAR autoantibodies from antibody‐secreting cells in CSF of patients with NMDAR encephalitis.7 Unexpectedly, several NR1‐reactive autoantibodies from different patients were unmutated, suggesting that they had not been selected for high affinity during germinal center reactions and instead were derived from activated naïve B cells. We therefore determined whether these germline NR1 antibodies showed functional effects similar to affinity‐matured NR1 autoantibodies leading to synaptic dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant Monoclonal NMDAR Antibodies

Recombinant monoclonal human NR1 IgG autoantibodies were generated as described.7, 8 The study was approved by the Charité University hospital Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from each subject. The control antibody (mGo53) is a nonreactive isotype‐matched human antibody.9 Immunostaining, using primary hippocampal neurons, unfixed mouse brain sections, HEK cell‐expressed NR1 N368Q mutants, and brain sections after intravenous antibody injection, followed our established protocols.7 We generated germline counterpart versions from maturated monoclonal NR1 antibodies with best matching variable V(D)J genes and elimination of somatic hypermutations.10 Relative affinity curves were calculated based on concentration‐dependent antibody binding to hippocampal sections, adapted from previous work using HEK cells transfected with the NR1 subunit.11 For bilateral intracerebroventricular injection, 200 μg of antibodies were infused over 14 days using osmotic minipumps.12

Super‐Resolution Imaging

Direct stochastic reconstruction microscopy (dSTORM) was performed in primary hippocampal neurons (DIV 14) as described.12 Human NR1 autoantibody (clone #003‐109; 4 μg/ml) and polyclonal guinea pig anti‐Homer‐1 (1:300; Synaptic Systems GmbH, Goettingen, Germany) were used as primary antibodies followed by AlexaFluor‐647 goat/anti‐human (1:200; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and CF‐568 donkey/anti–guinea pig (1:200; Biotium, Fremont, CA) as secondary antibodies.

Electrophysiological Recordings

Autaptic murine hippocampal neurons (DIV 14‐17) were incubated with 1 or 5 μg/ml human NR1 (#003‐109) or control antibody at 37°C for 3 or 24 hours. Data were acquired as described.13 Cells were recorded in standard intra‐ and extracellular solutions, except for chemically induced NMDA responses, measured in extracellular solution containing 0 mM of Mg2+, 0.2 mM of CaCl2, and 10 μM of glycine, and evoked NMDA responses, measured in extracellular solution containing 0 mM of Mg2+, 2 mM of CaCl2, 10 μM of glycine, and 10 μM of NBQX (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK). For kinetics of synaptic NMDA responses, non‐silent traces from each cell were averaged and rise time and decay time constant (τ) measured from 10% to 90% or 90% to 10% of the peak, respectively. Decays were fitted with a double exponential and decay time constants for each of the fits converted to a weighted decay.

Homology Modeling

The homology model of the ATD of the human NMDA receptor was generated using the crystal structure of the rat NMDA receptor subunit, zeta‐1. The homology modeling application of MOE 2014.09 (“Molecular Operating Environment [MOE], 2014.09”, 2015) was used with 10 main chain models, each with one side chain. Samples were built using the amber12 force field.14

Results

Germline NR1 Autoantibodies Target the NMDAR in vitro and in vivo

The CSF autoantibody repertoire in NMDAR encephalitis contains NR1‐binding and non‐NR1‐binding antibodies.7 Across all 8 patients, NR1‐binding antibodies had significantly lower numbers of somatic hypermutations (SHM) in the Ig heavy (5.1 ± 4.0 versus 11.9 ± 8.3) and corresponding Ig light chains (3.9 ± 4.8 versus 7.2 ± 5.4) than non‐NR1‐binding antibodies (total, 9.0 ± 7.9 versus 19.1 ± 12.6 mean ± SD; p = 0.018, unpaired t test). Individual NR1 antibodies were even completely unmutated (#003‐109) or contained only silent SHM (#007‐142, #007‐169).7

The germline antibody, #003‐109, accounted for 1 of 41 (2.4%) of antibody‐secreting cells analyzed of this patient and showed the characteristic NR1 pattern on unfixed mouse brain sections (Fig 1A) and the NMDAR cluster distribution on primary hippocampal mouse neurons previously observed for mutated NR1 antibodies7 (Fig 1B). dSTORM of hippocampal neurons demonstrated NMDAR distribution at synapses, opposed to Homer1‐positive postsynaptic densities (Fig C). Intravenous injection of #003‐109 resulted in binding to cerebellar granule cells in vivo (Fig 1D), which was not detectable with the isotype control (Fig 1E). Intracerebroventricular injection of maturated (Fig 1G) and germline (Fig 1H) NR1 antibodies showed similar neuropil binding in the hippocampus.

Figure 1.

Target specificity of the germline NR1 autoantibody #003‐109. Immunofluorescence staining showed the characteristic NR1 pattern in the brain (A), in particular of hippocampal neuropil (A‐I) and cerebellar granule cells (A‐II, arrows). NMDAR‐expressing synaptic clusters were specifically labeled on primary hippocampal neurons (B; green: NR1, red: MAP2). dSTORM imaging confirmed NR1 expression in the synapse (C; purple: NR1, green: Homer1). Germline NR1 antibodies (D), but not isotype control antibodies (E), bound to cerebellar granule cells (arrows) 24 hours after intravenous injection together with lipopolysaccharide. Antibodies were present in the circulation as confirmed with stainings of the choroid plexus (D,E, inserts), in contrast to control brains of untreated mice (F). Intracerebroventricular injection of maturated (G) and germline (H) NR1 antibodies showed similar neuropil binding in the hippocampus. Scale bars: A = 2 mm; A‐I/A‐II = 500 μm; B = 20 μm; C = 1 μm (inserts: 200 nm); F = 100 μm (for D–F); G,H = 100 μm. DAPI = 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole; MAP2, microtubule‐associated protein 2; NMDAR = N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor.

Binding of Mutated, Germline, and Reverted Antibodies to NR1

Binding of #003‐109 was prevented by the single‐amino‐acid mutation, N368Q, in the ATD of NR1 (Fig 2A,B).7 To model the possible antibody/ATD interaction in silico, protein‐protein docking was performed against ATD using ClusPro (Fig 2C). ATD residues N368 and G369 are embedded in the protein‐protein interface forming a network of H‐bonds with the antibody residues (Fig 2D). N368 is the only amino acid on the receptor side that stabilizes the binding to both, the antibody heavy and the light chains (Fig 2D). Binding curves of patient‐derived germline NR1 antibodies showed generally lower relative affinity to hippocampal sections than mutated antibodies (Fig 2E–G). However, reverting mutated patient antibodies to germline changed the binding strengths only minimally, suggesting a similar functional role already of the naïve antibodies (Fig 2H).

Figure 2.

Interactions between germline antibodies and the NMDAR. Germline antibodies strongly bound to NR1 protein in transiently transfected HEK cells (A). In contrast, NR1 N368Q mutation completely omitted human antibody binding (B). Predicted binding pose of antibody #003‐109 (blue, with complementarity determining regions in dark blue) to the ATD (green), the 3D model of the antibody, was generated by the antibody modeling tool of MOE2014.09 (C). Interaction of the key residues N368 and G369 in the H‐bond network is illustrated in ball and stick mode; interactions are shown as black lines with the molecule distance in Å (D). Binding strengths with increasing concentrations of NR1 antibodies were determined by fluorescence intensities of hippocampal brain sections, exemplarily shown for a mutated (E) and germline antibody (F). Plotting these binding strengths against antibody concentrations showed the range of relative affinity curves of monoclonal patient‐derived NR1 autoantibodies with weaker binding of the germline antibodies (G). “Back‐mutation” of the high‐affinity NR1 antibodies to germline configuration (GL = germline; two possible germline antibodies for #003‐102) showed only minimal reduction of the binding strengths (H). Data are mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent stainings (G,H) each representing the mean of three hippocampal areas (yellow rectangles in E) per antibody/concentration. Scale bars: A,B = 20 μm; E = 100 μm (for E,F). DAPI = 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole; hNR1/rbNR1 = human/rabbit NR1 antibody; NMDAR = N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor.

Unmutated NR1 Antibodies Selectively Reduced Total and Synaptic NMDAR Currents

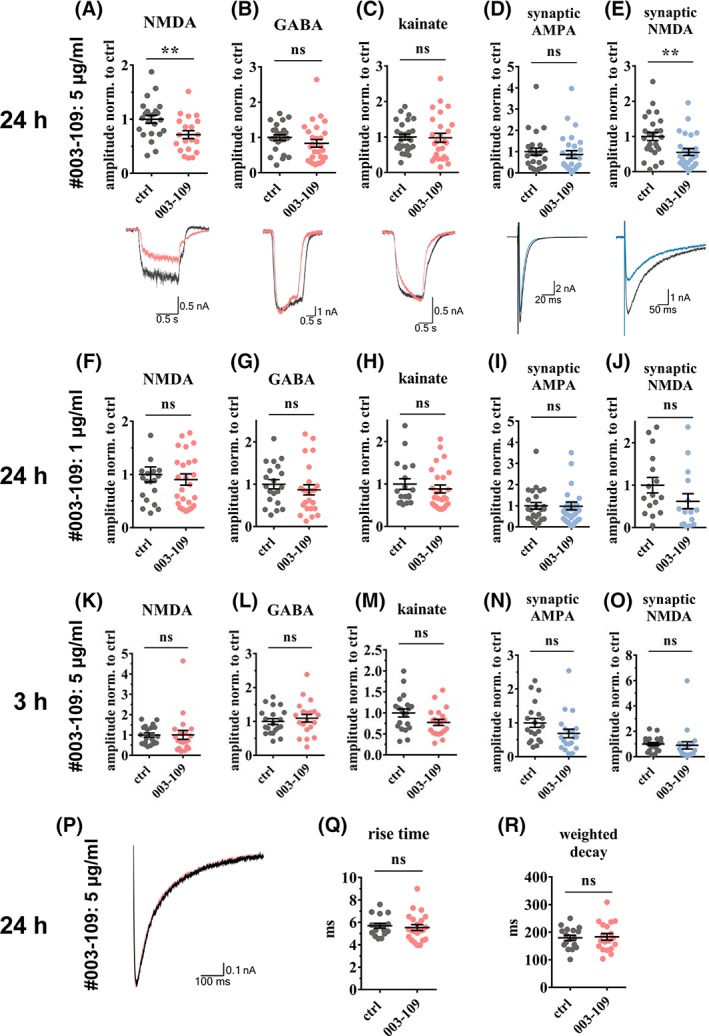

We expected smaller electrophysiological changes induced by antibody #003‐109 compared to mutated NR1 antibodies, given the lower binding to murine brain (Fig 2E,F). Indeed, incubation of autaptic mouse hippocampal neurons with 5 μg/ml of germline antibody #003‐109 for 24 hours resulted in ~30% reduction of the total NMDA currents compared to the isotype control antibody (Fig 3A). The antibody effect was specific, given that the total gamma‐aminobutyric acid (GABA)‐ and kainate‐mediated currents remained unaffected after application of 5 μM of GABA or 20 μM of kainate, respectively (Fig 3B,C). Measuring synaptic responses in the presence of 10 μM of glycine,10 μM of NBQX, and 0 mM of Mg2+, NR1 antibody treatment also reduced synaptic NMDA currents by ~45%, while synaptic alpha‐amino propionic acid (AMPA) currents did not differ from controls (Fig 3D,E). In contrast to higher‐affinity mutated NR1 antibodies,7 the effects were not detectable with lower antibody concentrations (1 μg/ml of #003‐109; Fig 3F–J). In addition, shorter incubation for 3 hours with germline antibody was not sufficient to reduce synaptic or whole‐cell NMDA currents (Fig 3K–O). The kinetics of synaptic NMDA responses were not altered by NR1 antibody treatment (Fig 3P–R).

Figure 3.

Germline antibody #003‐109 reduced total and synaptic NMDA currents. Patch clamp whole‐cell recordings of autaptic murine neuronal cultures showed that 24 hours of incubation with antibody #003‐109 (5 μg/ml) selectively reduced total NMDA currents by 30% (A, p = 0.009), but not GABA or kainate currents (B,C), which were evoked by a 1‐second bath application of 10 μM of NMDA (A), 5 μM of GABA (B), or 20 μM of kainate (C), respectively. Synaptic NMDA currents, evoked in the presence of 10 μM of glycine, 10 μM of NBQX, and 0Mg2+, showed 45% reduction (E, p = 0.003) whereas synaptic AMPA currents remained unchanged (D). The selective effect on NMDA currents was abolished at lower concentrations of antibody #003‐109 (1 μg/ml; F–J). Total GABA and kainate and synaptic AMPA currents were not affected (G–I), while a trend toward reduced synaptic NMDA currents persisted at this antibody concentration (J, p = 0.152). Established concentrations of antibody #003‐109 (5 μg/ml), but shorter incubation of 3 hours, were not sufficient to cause reduced NMDA currents (K–O). Averaged traces of exemplary cells incubated for 24 hours with germline and control antibodies (5 μg/ml) were scaled to 1 nA for easier comparison (P) and showed equal rise time (Q) and weighted decay (R) of synaptic NMDA currents. Data are mean ± SEM, Student's t test, n = 20 to 28 (A–E), n = 15 to 32 (F–J), or n = 20 (K–O) cells per group from four independent experiments. AMPA = alpha‐amino propionic acid; ctrl = control; GABA = gamma‐aminobutyric acid; NMDA = N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate; ns = not significant.

Discussion

The present study followed the unexpected observation that human NR1 autoantibodies have low numbers of somatic hypermutations and that even germline‐encoded, unmutated NR1 autoantibodies are found in patients with NMDAR encephalitis. Patient‐derived germline antibodies had lower binding compared to mutated NR1 antibodies, but were also functional in selectively reducing synaptic NMDAR currents in a dose‐ and time‐dependent manner. They should be present in the patient's CSF as clone #003‐109 derived from a CSF plasma cell, which is believed to continuously produce several thousand IgG molecules per second.15, 16

The finding of germline‐configured functional NMDAR autoantibodies in the human repertoire might explain the mysterious observation of the high frequency of serum NMDAR antibodies in different diseases and blood donors.17 Generally, B cells carrying high‐affinity autoreactive antibodies undergo negative selection, while low‐affinity antibodies might remain in the repertoire.18 Thus, the here identified NR1 autoantibodies likely did not see their antigen during B cell development, or were of sufficiently low affinity to remain part of the naïve B cell repertoire,19 and might therefore be present in every individual. The important role of naïve B cells in NMDAR encephalitis was recently suggested, although the experimental approach did not allow information on antibody mutations.20 Likewise, autoreactive naïve B cells were recently observed in a related antibody‐mediated disease, neuromyelitis optica.21 It is still an open question how NMDAR‐expressing tumors that might contain germinal center‐like structures,2, 20, 22, 23 viral brain infections,3, 4 or additional factors lead to the maturation and expansion of NR1 antibody‐producing cells in relatively rare cases, ultimately resulting in NMDAR encephalitis. In ovarian teratomas, tumor‐intrinsic abnormalities, such as organized dysplastic neurons, may facilitate the development of NMDAR autoimmunity.22 No clear distinction between the here examined germline and mutated antibodies was noted in patients without a tumor (#007, #008) compared to a patient with an ovarian carcinoma (#003).

Distinct unmutated (“naturally occurring”) autoantibodies are innate‐like components of the immune system that facilitate the clearance of invading pathogens, induce apoptosis in cancer cells, promote remyelination, or delay disease progression in murine models of inflammation and neurodegeneration.24, 25, 26 May unmutated NMDAR autoantibodies have been similarly selected because of evolutionary importance (eg, for neutralization of released NMDAR protein), thereby preventing dysfunctional immune stimulation? Indeed, preexisting NMDAR antibodies were associated with smaller lesion size after stroke in one study, possibly related to reduction of glutamate‐mediated excitotoxicity.27 Also, there are examples of other germline antibodies that are reactive to commensal bacteria at mucosal barriers, but at the expense of pathogenic reactivity to self‐proteins.28

Future studies should examine antibody effects beyond receptor internalization29 and clarify under which conditions NR1 (and potentially further) autoantibody‐producing cells escape negative selection and expand to cause encephalitis. They should also address whether and at which concentrations functional NMDAR autoantibodies are part of the healthy human naïve B cell repertoire and may thus contribute to a broader spectrum of neuropsychiatric symptoms than previously assumed.

Author Contributions

N.K.W., J.K., H.W., G.W., and H.P. contributed to the conception and design of the study. N.K.W., J.K., E.A., A.v.C., J.L., M.S.M., S.M.R., C.S., L.S., C.G., F.A., M.N., C.C.G., H.W., G.W., and H.P. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. N.K.W., J.K., E.A., A.v.C., M.S.M., S.M.R., L.S., C.G., H.W., G.W., and H.P. contributed to drafting the text and preparing the figures.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

Acknowledgment

This study has been supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG; to H.P.: PR 1274; 2‐1, to C.G.: CRC/TRR166, TP B02), Focus Area DynAge (Freie Universität Berlin and Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, to H.P. and G.W.).

References

- 1. Dalmau J, Gleichman, AJ , Hughes EG, et al. Anti‐NMDA‐receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:1091–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long‐term outcome in patients with anti‐NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Armangue T, Leypoldt F, Malaga I, et al. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is a trigger of brain autoimmunity. Ann Neurol 2014;75:317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prüss H, Finke C, Höltje M, et al. N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor antibodies in herpes simplex encephalitis. Ann Neurol 2012;72:902–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Malviya M, Barman S, Golombeck KS, et al. NMDAR encephalitis: passive transfer from man to mouse by a recombinant antibody. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2017;4:768–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Planaguma J, Leypoldt F, Mannara F, et al. Human N‐methyl D‐aspartate receptor antibodies alter memory and behaviour in mice. Brain 2015;138:94–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kreye J, Wenke NK, Chayka M, et al. Human cerebrospinal fluid monoclonal N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor autoantibodies are sufficient for encephalitis pathogenesis. Brain 2016;139:2641–2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tiller T, Meffre E, Yurasov S, et al. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT‐PCR and expression vector cloning. J Immunol Methods 2008;329:112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, et al. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science 2003;301:1374–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murugan R, Buchauer L, Triller G, et al. Clonal selection drives protective memory B cell responses in controlled human malaria infection. Sci Immunol 2018;3:eaap8029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ly LT, Kreye J, Jurek B, et al. Affinities of human NMDA receptor autoantibodies: implications for disease mechanisms and clinical diagnostics. J Neurol 2018;265:2625–2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Werner C, Pauli M, Doose S, et al. Human autoantibodies to amphiphysin induce defective presynaptic vesicle dynamics and composition. Brain 2016;139:365–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zimmermann J, Herman MA, Rosenmund C. Co‐release of glutamate and GABA from single vesicles in GABAergic neurons exogenously expressing VGLUT3. Front Synaptic Neurosci 2015;7:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham TE, et al. AMBER 12. San Francisco, CA: University of California; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Helmreich E, Kern M, Eisen HN. The secretion of antibody by isolated lymph node cells. J Biol Chem 1961;236:464–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hibi T, Dosch HM. Limiting dilution analysis of the B cell compartment in human bone marrow. Eur J Immunol 1986;16:139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dahm L, Ott C, Steiner J, et al. Seroprevalence of autoantibodies against brain antigens in health and disease. Ann Neurol 2014;76:82–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Melchers F. Checkpoints that control B cell development. J Clin Invest 2015;125:2203–2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meffre E, Wardemann H. B‐cell tolerance checkpoints in health and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol 2008;20:632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Makuch M, Wilson R, Al‐Diwani A, et al. N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor antibody production from germinal center reactions: therapeutic implications. Ann Neurol 2018;83:553–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wilson R, Makuch M, Kienzler AK, et al. Condition‐dependent generation of aquaporin‐4 antibodies from circulating B cells in neuromyelitis optica. Brain 2018;141:1063–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Day GS, Laiq S, Tang‐Wai DF, Munoz DG. Abnormal neurons in teratomas in NMDAR encephalitis. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:717–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dabner M, McCluggage WG, Bundell C, et al. Ovarian teratoma associated with anti‐N‐methyl D‐aspartate receptor encephalitis: a report of 5 cases documenting prominent intratumoral lymphoid infiltrates. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2012;31:429–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu X, Denic A, Jordan LR, et al. A natural human IgM that binds to gangliosides is therapeutic in murine models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Dis Model Mech 2015;8:831–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wootla B, Watzlawik JO, Warrington AE, et al. Naturally occurring monoclonal antibodies and their therapeutic potential for neurologic diseases. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:1346–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rodriguez M, Lennon VA, Benveniste EN, Merrill JE. Remyelination by oligodendrocytes stimulated by antiserum to spinal cord. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1987;46:84–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zerche M, Weissenborn K, Ott C, et al. Preexisting serum autoantibodies against the NMDAR subunit NR1 modulate evolution of lesion size in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2015;46:1180–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schickel JN, Glauzy S, Ng YS, et al. Self‐reactive VH4‐34‐expressing IgG B cells recognize commensal bacteria. J Exp Med 2017;214:1991–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gleichman AJ, Spruce LA, Dalmau J, et al. Anti‐NMDA receptor encephalitis antibody binding is dependent on amino acid identity of a small region within the GluN1 amino terminal domain. J Neurosci 2012;32:11082–11094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]