Abstract

Background

In the phase 1–2 portion of an adaptive trial, REGEN-COV, a combination of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab, reduced the viral load and number of medical visits in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). REGEN-COV has activity in vitro against current severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants of concern.

Methods

In the phase 3 portion of an adaptive trial, we randomly assigned outpatients with Covid-19 and risk factors for severe disease to receive various doses of intravenous REGEN-COV or placebo. Patients were followed through day 29. A prespecified hierarchical analysis was used to assess the end points of hospitalization or death and the time to resolution of symptoms. Safety was also evaluated.

Results

Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause occurred in 18 of 1355 patients in the REGEN-COV 2400-mg group (1.3%) and in 62 of 1341 patients in the placebo group who underwent randomization concurrently (4.6%) (relative risk reduction [1 minus the relative risk], 71.3%; P<0.001); these outcomes occurred in 7 of 736 patients in the REGEN-COV 1200-mg group (1.0%) and in 24 of 748 patients in the placebo group who underwent randomization concurrently (3.2%) (relative risk reduction, 70.4%; P=0.002). The median time to resolution of symptoms was 4 days shorter with each REGEN-COV dose than with placebo (10 days vs. 14 days; P<0.001 for both comparisons). REGEN-COV was efficacious across various subgroups, including patients who were SARS-CoV-2 serum antibody–positive at baseline. Both REGEN-COV doses reduced viral load faster than placebo; the least-squares mean difference in viral load from baseline through day 7 was −0.71 log10 copies per milliliter (95% confidence interval [CI], −0.90 to −0.53) in the 1200-mg group and −0.86 log10 copies per milliliter (95% CI, −1.00 to −0.72) in the 2400-mg group. Serious adverse events occurred more frequently in the placebo group (4.0%) than in the 1200-mg group (1.1%) and the 2400-mg group (1.3%); infusion-related reactions of grade 2 or higher occurred in less than 0.3% of the patients in all groups.

Conclusions

REGEN-COV reduced the risk of Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause, and it resolved symptoms and reduced the SARS-CoV-2 viral load more rapidly than placebo. (Funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and others; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04425629.)

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19), and as of September 2021, it has infected more than 230 million people and led to approximately 4.7 million deaths globally.1 Although most patients with Covid-19 receive care in the outpatient setting, some have disease that progresses to severe illness leading to hospitalization or death.2-6 Several investigational therapeutic agents, including REGEN-COV (previously known as REGN-COV2), are available under emergency use authorization. However, there have been limited clinical data to support their wider use and no approved treatments to reduce the risk of hospitalization or death among patients with mild-to-moderate Covid-19. There is also a need for therapeutic agents that remain effective against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, which contain mutations that attenuate immunity resulting from previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccination, and some monoclonal antibodies.7-10

To develop a therapeutic agent that would retain activity against emerging variants, high-throughput screening was undertaken to generate an antibody cocktail consisting of two SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies against distinct, nonoverlapping epitopes on the spike protein.11-13 In vitro studies showed that this antibody cocktail, REGEN-COV, retains activity against current variants of concern and variants of interest, including B.1.1.7 (or alpha), B.1.429 (or epsilon), B.1.617.2 (or delta), and E484K-containing variants such as B.1.351 (or beta), P.1 (or gamma), and B.1.526 (or iota).9,14 In the phase 1–2 portion of this phase 1–3 adaptive, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, REGEN-COV was efficacious in symptomatic outpatients, in whom it reduced the SARS-CoV-2 viral load and the need for medical attention related to Covid-19.15,16 Here, we report the results of the primary analysis of the phase 3 portion of this trial.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

The phase 3 portion of this trial involving outpatients with Covid-19 comprised cohort 1 (patients who were ≥18 years of age), cohort 2 (those who were <18 years of age), and cohort 3 (those who were pregnant at randomization). Initially, the patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive intravenous REGEN-COV at a dose of 2400 mg (1200 mg each of casirivimab and imdevimab) or 8000 mg (4000 mg of each antibody) or intravenous placebo (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org).

On the basis of results of the phase 1–2 portion of the trial, which showed that the 2400-mg and 8000-mg doses had similar antiviral and clinical efficacy and that most clinical events occurred in high-risk patients,15 the trial was amended on November 14, 2020, so that patients who were subsequently enrolled had at least one risk factor for severe Covid-19 and were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive intravenous REGEN-COV at a dose of 1200 mg (600 mg of each antibody) or 2400 mg (1200 mg of each antibody) or intravenous placebo. On February 25, 2021, on the basis of a recommendation from an independent data and safety monitoring committee, patients were no longer randomly assigned to receive placebo. The phase 3 primary efficacy analysis presented here involved cohort 1 patients who were assigned to receive either 2400 mg or 1200 mg of REGEN-COV, with their concurrent placebo groups serving as a control; the trial involving cohorts 2 and 3 is ongoing.

Regeneron designed the trial; gathered the data, together with the trial investigators; and analyzed the data. An independent data and safety monitoring committee reviewed unblinded data to make recommendations about trial modification and termination.

The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and all applicable regulatory requirements. The local institutional review board or ethics committee at each trial center oversaw trial conduct and documentation. All the patients provided written informed consent before participating in the trial. Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix.

Patients

Eligible patients in cohort 1 were 18 years of age or older and were not hospitalized. These patients had a confirmed local SARS-CoV-2–positive diagnostic test result no more than 72 hours before randomization, with the onset of any Covid-19 symptom, as determined by the investigator, occurring no more than 7 days before randomization. Randomization into the initial phase 3 portion of the trial was stratified according to country and the presence of risk factors for severe Covid-19. In the amended phase 3 portion of the trial, only patients with at least one risk factor for severe Covid-19 were eligible. The full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in the protocol, available at NEJM.org.

All the patients were assessed at baseline for anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies — anti-spike (S1) IgA, anti-spike (S1) IgG, and anti-nucleocapsid IgG — and were categorized for the analyses as serum antibody–negative (if all available test results were negative), serum antibody–positive (if any available test result was positive), or other (inconclusive or unknown results).

Intervention and Assessments

At baseline (day 1), REGEN-COV (diluted in normal saline solution) or saline placebo was administered intravenously. The solutions were indistinguishable and were prepared by qualified personnel who were not associated with the conduct of the trial. Hospitalizations were assessed to be related to Covid-19 by the investigator. The 23-item Symptoms Evolution of COVID-19 instrument, an electronic diary, was used to assess Covid-19 symptoms daily.17 Quantitative virologic analysis of nasopharyngeal swab samples and serum antibody testing, as previously described, were conducted in a central laboratory.16

End Points

The primary and two key secondary end points were tested hierarchically (Table S1). The primary end point was the percentage of patients with at least one Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause through day 29. The key secondary clinical end points were the percentage of patients with at least one Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause from day 4 through day 29 and the time to resolution of Covid-19 symptoms (details are provided in the Supplementary Methods section). For the end point of resolution of symptoms, data on 19 of the 23 symptoms recorded were analyzed.

Data on targeted adverse events were collected in this trial. The safety end points consisted of serious adverse events and adverse events of special interest (i.e., hypersensitivity events of grade 2 or higher, infusion-related reactions, and adverse events for which medical attention at a health care facility was warranted).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis plan for the current analysis (available with the protocol) was finalized before database lock and unblinding in the phase 3 cohort 1; the primary analysis did not include patients from the previously reported phase 1–2 portion of the trial.15,16 The full analysis set included all symptomatic patients who underwent randomization. As prespecified in the statistical analysis plan, efficacy analyses were performed in a modified full analysis set, defined as all patients who were confirmed by means of quantitative reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) testing at a central laboratory to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 at baseline and who had at least one risk factor for severe Covid-19. Additional analyses involved patients without risk factors for severe Covid-19. Safety was assessed in patients in the full analysis set who received REGEN-COV or placebo.

The percentage of patients with at least one Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause was compared between each dose group and concurrent placebo group with the use of the stratified Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, with country as a stratification factor. P values from the stratified Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test and 95% confidence intervals for relative risk reduction were calculated with the Farrington–Manning method.18 The time to resolution of Covid-19 symptoms was assessed in patients with a baseline total severity score of more than 3 (on a scale from 0 to 38, with higher scores indicating an increased burden of symptoms) and analyzed with the use of the stratified log-rank test, with country as a stratification factor. Median times and associated 95% confidence intervals were derived with the use of the Kaplan–Meier method. The hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated with the use of the Cox regression model.

Analyses of the primary and key secondary end points were conducted at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 with the use of a hierarchical testing strategy to control for type I error. For the reporting of other secondary end points and analyses, the widths of the confidence intervals were not adjusted for multiplicity. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Additional statistical methods are described in the statistical analysis plan.

Results

Trial Population

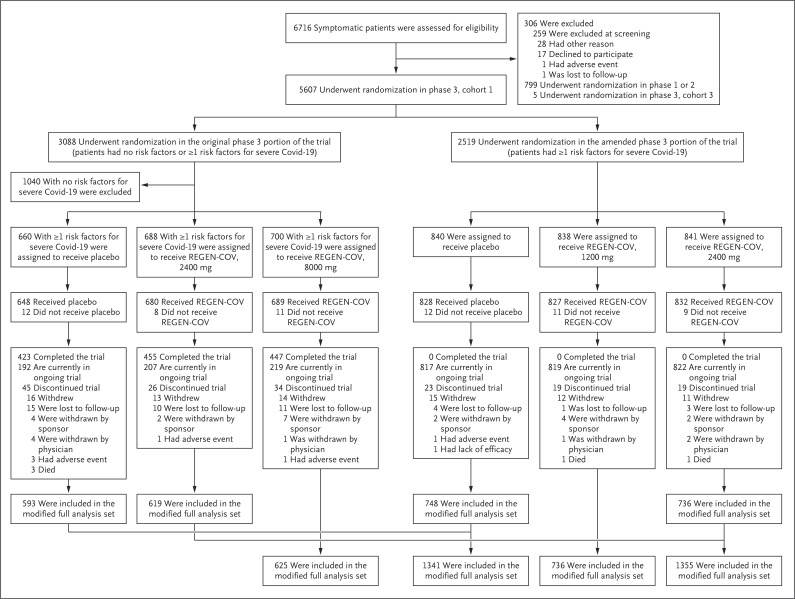

Patients were enrolled between September 24, 2020, and January 17, 2021. Initially, in the original phase 3 portion of the trial, 3088 patients, with or without risk factors for severe Covid-19, were randomly assigned to receive a single intravenous dose of REGEN-COV (8000 mg or 2400 mg) or placebo. In the amended phase 3 portion of the trial, an additional 2519 patients with at least one risk factor for severe Covid-19 were randomly assigned to receive a single dose of REGEN-COV (2400 mg or 1200 mg) or placebo (Figure 1). The median follow-up was 45 days, and 96.6% of the patients had more than 28 days of follow-up.

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, Treatment, and Analysis.

In the original phase 3 portion of the trial, Regeneron requested that 2, 1, and 5 patients in the placebo, REGEN-COV 2400-mg, and REGEN-COV 8000-mg groups, respectively, withdraw from the trial because these patients underwent randomization in error. In the amended phase 3 portion of the trial, Regeneron requested that 2, 4, and 2 patients in the placebo, REGEN-COV 1200-mg, and REGEN-COV 2400-mg groups, respectively, withdraw from the trial because these patients underwent randomization in error. The modified full analysis set included all patients who were confirmed by means of quantitative reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction testing at a central laboratory to be positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 at baseline and who had at least one risk factor for severe coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19).

The primary efficacy population included patients with at least one risk factor for severe Covid-19 and a test for SARS-CoV-2 confirmed at a central laboratory to be positive at baseline (modified full analysis set) (Figure 1). Among the 4057 patients in the modified full analysis set, demographic and baseline medical characteristics were balanced between the REGEN-COV and placebo groups (Table 1, and Table S2). In the overall modified full analysis set, the median age was 50 years (interquartile range, 38 to 59), 14% were at least 65 years of age, 49% were men, and 35% were Hispanic; the most common risk factors were obesity (in 58%), age of 50 years or older (52%), and cardiovascular disease (36%). A total of 3% of the patients were immunocompromised (Table S3).

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients in the Modified Full Analysis Set.*.

| Characteristic | REGEN-COV 2400 mg (N=1355) |

Placebo 2400 mg (N=1341)† |

REGEN-COV 1200 mg (N=736) |

Placebo 1200 mg (N=748) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) — yr | 50.0 (39.0–60.0) | 50.0 (37.0–58.0) | 48.5 (37.0–57.5) | 48.0 (35.0–57.0) |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 656 (48.4) | 633 (47.2) | 364 (49.5) | 352 (47.1) |

| Race or ethnic group — no. (%)‡ | ||||

| White | 1161 (85.7) | 1136 (84.7) | 595 (80.8) | 611 (81.7) |

| Black | 67 (4.9) | 66 (4.9) | 38 (5.2) | 38 (5.1) |

| Asian | 52 (3.8) | 56 (4.2) | 38 (5.2) | 36 (4.8) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 464 (34.2) | 471 (35.1) | 312 (42.4) | 295 (39.4) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 19 (1.4) | 13 (1.0) | 17 (2.3) | 10 (1.3) |

| Unknown | 28 (2.1) | 43 (3.2) | 36 (4.9) | 37 (4.9) |

| Not reported | 24 (1.8) | 26 (1.9) | 10 (1.4) | 15 (2.0) |

| Body-mass index§ | 31.09±6.33 | 31.19±6.63 | 31.54±7.31 | 31.07±6.46 |

| Obesity — no. (%)¶ | 787 (58.1) | 772 (57.6) | 410 (55.7) | 427 (57.1) |

| Viral load in nasopharyngeal swab | ||||

| No. of patients | 1353 | 1333 | 734 | 744 |

| Median viral load (range) — log10 copies/ml | 7.01 (2.6–10.0) | 6.95 (2.6–10.2) | 6.92 (2.6–10.5) | 6.85 (2.6–10.2) |

| Serum C-reactive protein level | ||||

| No. of patients | 1242 | 1243 | 713 | 724 |

| Median level (range) — mg/liter | 4.615 (0.11–354.16) |

4.940 (0.10–242.73) |

4.910 (0.11–238.53) |

4.865 (0.16–227.45) |

| Serum antibody status — no. (%) | ||||

| Negative | 940 (69.4) | 930 (69.4) | 500 (67.9) | 519 (69.4) |

| Positive | 323 (23.8) | 297 (22.1) | 177 (24.0) | 164 (21.9) |

| Other | 92 (6.8) | 114 (8.5) | 59 (8.0) | 65 (8.7) |

| Median time from symptom onset to randomization (IQR) — days | 3.0 (2–5) | 3.0 (2–5) | 3.0 (2–5) | 3.0 (2–4) |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. The modified full analysis set included all patients who were confirmed by means of quantitative reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction testing at a central laboratory to be positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 at baseline and who had at least one risk factor for severe coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). Risk factors for severe Covid-19 include an age of more than 50 years, obesity, cardiovascular disease (including hypertension), chronic lung disease (including asthma), chronic metabolic disease (including diabetes), chronic kidney disease (including receipt of dialysis), chronic liver disease, and an immunocompromised condition (immunosuppression or receipt of immunosuppressants). Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. IQR denotes interquartile range.

The placebo group of 1341 patients who underwent randomization concurrently with the group that received 2400 mg of REGEN-COV included the placebo group of 748 patients who underwent randomization concurrently with the group that received 1200 mg of REGEN-COV.

Race and ethnic group were reported by the patients.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Obesity is defined as a body-mass index of 30 or higher.

The median viral load on nasopharyngeal RT-PCR was 6.98 log10 copies per milliliter (range, 5.45 to 7.85), and the majority of patients (69%) were SARS-CoV-2 serum antibody–negative at baseline; the high median viral load and the lack of an endogenous immune response at baseline suggested that enrolled patients were in the early phase of infection. At randomization, the patients reported that they had had Covid-19 symptoms for a median of 3 days (interquartile range, 2 to 5). The nasopharyngeal viral load, serum antibody–negative status, and median duration of Covid-19 symptoms at randomization were similar across the trial groups. The demographic and baseline medical characteristics of the patients in the REGEN-COV (8000 mg) modified full analysis set and the concurrent placebo group are shown in Table S4.

Natural History of Covid-19 in Outpatients

Among the patients who received placebo, there was an association between the baseline viral load and Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause. A total of 55 of 876 patients (6.3%) with a high baseline viral load (>106 copies per milliliter) were hospitalized or died, as compared with 6 of 457 patients (1.3%) with a lower viral load (≤106 copies per milliliter) (Table S5).

Patients in the placebo group who were serum antibody–negative at baseline had higher median viral loads at baseline than those who were serum antibody–positive (7.45 log10 copies per milliliter and 4.96 log10 copies per milliliter, respectively). It also took longer for the viral levels in patients in the placebo group who were serum antibody–negative at baseline to fall below the lower limit of quantification (Fig. S2).

Despite these population-level observations, the baseline serum antibody status of patients who received placebo was not predictive of subsequent Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause, because the incidences of these outcomes were similar among patients who were serum antibody–negative and those who were serum antibody–positive (49 of 930 patients [5.3%] and 12 of 297 patients [4.0%], respectively). The finding that serum antibody–positive status did not have a predictive value with respect to the reduction in the incidences of hospitalization or death suggests that some patients had an ineffective immune response. For example, patients in the placebo group who were serum antibody–positive but still had disease progression leading to hospitalization or death had high viral loads at baseline and day 7, similar to those in the placebo group who were serum antibody–negative and were hospitalized or died (Table S6).

Efficacy

Primary End Point

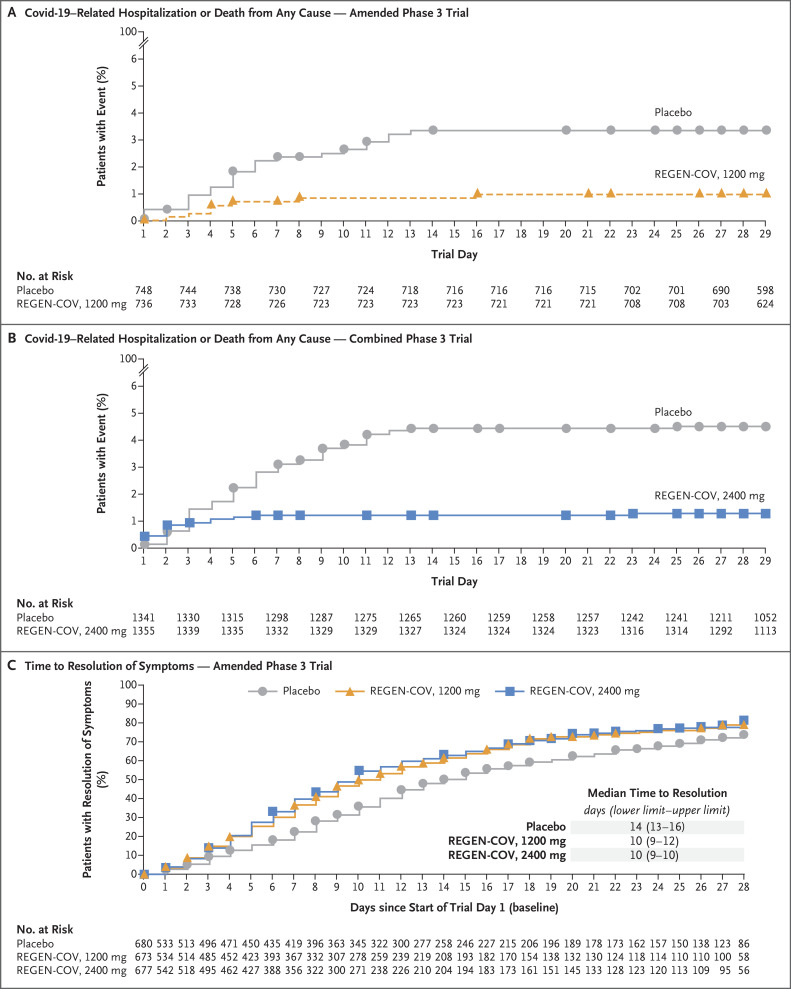

Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause occurred in 18 of 1355 patients in the REGEN-COV 2400-mg group (1.3%) and in 62 of 1341 patients in the placebo group who underwent randomization concurrently (4.6%) (relative risk reduction [1 minus the relative risk], 71.3%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 51.7 to 82.9; P<0.001); these outcomes occurred in 7 of 736 patients in the REGEN-COV 1200-mg group (1.0%) and in 24 of 748 patients in the placebo group who underwent randomization concurrently (3.2%) (relative risk reduction, 70.4%; 95% CI, 31.6 to 87.1; P=0.002) (Table 2, Figure 2A and 2B, and Table S7). Five deaths occurred during the efficacy assessment period, including one in the REGEN-COV 2400-mg group, one in the REGEN-COV 1200-mg group, and three in the placebo group. Similar decreases in Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause were observed across subgroups, including in patients who were serum antibody–positive at baseline (Table 2, and Fig. S3). REGEN-COV was also associated with decreases in hospitalization for any cause or death from any cause (Table S8).

Table 2. Hierarchical End Points.

| Hypothesis-Testing Hierarchy and Comparison* | Treatment Effect | Relative Risk Reduction % (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with ≥1 Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause through day 29 — no./total no. (%) | |||

| 2400 mg vs. placebo | 18/1355 (1.3) vs. 62/1341 (4.6) | 71.3 (51.7–82.9) | <0.001 |

| 1200 mg vs. placebo | 7/736 (1.0) vs. 24/748 (3.2) | 70.4 (31.6–87.1) | 0.002 |

| In patients with baseline viral load >106 copies/ml, 2400 mg vs. placebo | 13/924 (1.4) vs. 55/876 (6.3) | 77.6 (59.3–87.7) | <0.001 |

| In patients who were serum antibody–negative at baseline, 2400 mg vs. placebo | 12/940 (1.3) vs. 49/930 (5.3) | 75.8 (54.7–87.0) | <0.001 |

| In patients with baseline viral load >106 copies/ml, 1200 mg vs. placebo | 6/482 (1.2) vs. 20/471 (4.2) | 70.7 (27.6–88.1) | 0.005 |

| In patients who were serum antibody–negative at baseline, 1200 mg vs. placebo | 3/500 (0.6) vs. 18/519 (3.5) | 82.7 (41.6–94.9) | 0.001 |

| Patients with ≥1 Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause, day 4 through day 29 — no./total no. (%) | |||

| 2400 mg vs. placebo | 5/1351 (0.4) vs. 46/1340 (3.4) | 89.2 (73.0–95.7) | <0.001 |

| 1200 mg vs. placebo | 5/735 (0.7) vs. 18/748 (2.4) | 71.7 (24.3–89.4) | 0.010 |

| Median time to resolution of Covid-19 symptoms — days | |||

| 2400 mg vs. placebo | 10 vs. 14; 4-day faster resolution |

<0.001 | |

| 1200 mg vs. placebo | 10 vs. 14; 4-day faster resolution |

<0.001 |

All analyses were conducted in the modified full analysis set, which included all patients who were confirmed by means of quantified reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction testing of nasopharyngeal swabs to be positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 at randomization and who had at least one risk factor for severe Covid-19. The placebo group of 1341 patients who underwent randomization concurrently with the group that received 2400 mg of REGEN-COV included the placebo group of 748 patients who underwent randomization concurrently with the group that received 1200 mg of REGEN-COV.

Figure 2. Clinical Efficacy.

Panel A shows the percentage of patients who were hospitalized or died from any cause in the amended phase 3 portion of the trial. Panel B shows the percentage of patients who were hospitalized or died from any cause in the original and amended phase 3 portions of the trial combined. Panel C shows the time to resolution of symptoms in the amended phase 3 portion of the trial. The lower and upper confidence limits are shown.

Key Secondary End Points

The between-group difference in the percentage of patients with Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause was observed starting approximately 1 to 3 days after the patients received REGEN-COV or placebo (Figure 2A and 2B). After these first 1 to 3 days, 5 of 1351 patients in the REGEN-COV 2400-mg group (0.4%), 5 of 735 patients in the REGEN-COV 1200-mg group (0.7%), 46 of 1340 patients in the placebo group who underwent randomization concurrently with the REGEN-COV 2400-mg group (3.4%), and 18 of 748 patients in the placebo group who underwent randomization concurrently with the REGEN-COV 1200-mg group (2.4%) had Covid-19–related hospitalization or died (Table 2 and Fig. S4).

The median time to resolution of Covid-19 symptoms was 4 days shorter in both REGEN-COV dose groups than in the placebo groups (10 days vs. 14 days, respectively; P<0.001 each for 2400 mg and 1200 mg) (Table 2 and Figure 2C). The more rapid resolution of Covid-19 symptoms with either dose of REGEN-COV was evident by day 3. Both REGEN-COV doses were associated with similar improvements in resolution of symptoms across subgroups (Fig. S5).

Other Secondary End Points and Additional Analyses

The incidence of Covid-19–related hospitalization was lower among patients who received REGEN-COV than among those who received placebo (Table S9). Among patients who were hospitalized due to Covid-19, those in the REGEN-COV groups had shorter hospital stays and a lower incidence of admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) than those in the placebo groups (Table S10).

Covid-19–related hospitalization, emergency department visits, or death from any cause through day 29 occurred in fewer patients in the REGEN-COV groups than in the placebo groups (Table S11), and fewer patients in the REGEN-COV groups had worsening Covid-19 leading to any medically attended visit (hospitalization, an emergency department visit, a visit to an urgent care clinic or physician’s office, or a telemedicine visit) or death from any cause (Table S9). The clinical efficacy of REGEN-COV at a dose of 8000 mg is shown in Tables S12 and S13.

Fewer symptomatic patients without risk factors for severe Covid-19 had at least one Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause in the REGEN-COV groups than in the placebo groups, although there were few hospitalizations or deaths overall (Table S14). In patients without risk factors, the time to resolution of symptoms was 2 or 3 days shorter in patients who received REGEN-COV than in those who received placebo. Collectively, these data indicate a potential benefit of REGEN-COV, regardless of the presence or absence of baseline risk factors for severe Covid-19.

All REGEN-COV dose levels led to similar and more rapid declines in the viral load than placebo. The least-squares mean difference between 1200 mg, 2400 mg, and 8000 mg of REGEN-COV and placebo in the viral load from baseline through day 7 was −0.71 log10 copies per milliliter (95% CI, −0.90 to −0.53), −0.86 log10 copies per milliliter (95% CI, −1.00 to −0.72), and −0.87 log10 copies per milliliter (95% CI, −1.07 to −0.67), respectively (Figs. S6 through S8).

Safety

More patients had serious adverse events in the placebo group (4.0%) than in the three REGEN-COV groups (1.1 to 1.7%) (Table 3). More patients had adverse events that resulted in death in the placebo group (5 of 1843 patients [0.3%]) than in the REGEN-COV groups: 1 of 827 patients (0.1%) in the 1200-mg group, 1 of 1849 patients (<0.1%) in the 2400-mg group, and none of the 1012 patients in the 8000-mg group (Table 3 and Table S15). Most adverse events were consistent with complications of Covid-19 (Table S16), and the majority were not considered by the investigators to be related to the trial drug. Few patients had infusion-related reactions of grade 2 or higher (no patients in the placebo group; 2 patients in the 1200-mg group, 1 patient in the 2400-mg group, and 3 patients in the 8000-mg group) or hypersensitivity reactions (1 patient in the placebo group and 1 patient in the 2400-mg group) (Table 3). A similar safety profile was observed among the REGEN-COV doses, with no discernable imbalance in safety events.

Table 3. Serious Adverse Events and Adverse Events of Special Interest in the Safety Population.*.

| Event | REGEN-COV | Placebo (N=1843) |

Total (N=5531) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1200 mg (N=827) |

2400 mg (N=1849) |

8000 mg (N=1012) |

|||

| number of patients (percent) | |||||

| Serious adverse event that occurred or worsened during the observation period | |||||

| Any serious adverse event | 9 (1.1) | 24 (1.3) | 17 (1.7) | 74 (4.0) | 124 (2.2) |

| Any serious adverse event of special interest† | 1 (0.1) | 1 (<0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 6 (0.3) | 9 (0.2) |

| Adverse events of special interest that occurred or worsened during the observation period | |||||

| Grade ≥2 infusion-related reaction within 4 days | 2 (0.2) | 1 (<0.1) | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 6 (0.1) |

| Grade ≥2 hypersensitivity reaction within 29 days | 0 | 1 (<0.1) | 0 | 1 (<0.1) | 2 (<0.1) |

| Events leading to medical attention at a health care facility | |||||

| Related to Covid-19 | 15 (1.8) | 20 (1.1) | 11 (1.1) | 47 (2.6) | 93 (1.7) |

| Not related to Covid-19 | 0 | 7 (0.4) | 0 | 5 (0.3) | 12 (0.2) |

| Adverse events that occurred or worsened during the observation period | |||||

| Any event | 59 (7.1) | 142 (7.7) | 85 (8.4) | 189 (10.3) | 475 (8.6) |

| Grade 3 or grade 4 event | 11 (1.3) | 18 (1.0) | 15 (1.5) | 62 (3.4) | 106 (1.9) |

| Event leading to death | 1 (0.1) | 1 (<0.1) | 0 | 5 (0.3) | 7 (0.1) |

| Event leading to withdrawal from the trial | 0 | 1 (<0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (<0.1) | 4 (<0.1) |

| Event leading to infusion interruption† | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 2 (<0.1) |

Events listed here were not present at baseline or were an exacerbation of a preexisting condition that occurred during the observation period, which is defined as the time from administration of REGEN-COV or placebo to the final follow-up visit.

Events were defined as hypersensitivity reactions (grade ≥2), infusion-related reactions (grade ≥2), or medical attention at a health care facility, regardless of whether they were related to Covid-19.

Pharmacokinetics

The mean concentrations of casirivimab and imdevimab in serum increased in a dose-proportional manner and were consistent with linear pharmacokinetics for the single intravenous doses (Table S17). At the end of the infusion, the mean (±SD) concentrations of casirivimab and imdevimab in serum were 185±74.5 mg per liter and 192±78.9 mg per liter, respectively, with the REGEN-COV 1200-mg dose and 321±106 mg per liter and 321±112 mg per liter, respectively, with the REGEN-COV 2400-mg dose. At day 29, the mean concentrations of casirivimab and imdevimab in serum were 46.4±22.5 mg per liter and 38.3±19.6 mg per liter, respectively, with the REGEN-COV 1200-mg dose and 73.2±27.2 mg per liter and 60.0±22.9 mg per liter, respectively, with the REGEN-COV 2400-mg dose. The mean estimated half-life was 28.8 days for casirivimab and 25.5 days for imdevimab.

Discussion

Previous data from the phase 1–2 portion of this trial showed that in outpatients with Covid-19, REGEN-COV lowered the viral load, reduced the need for medical attention related to Covid-19, and may have reduced the risk of hospitalization.15,16 The phase 3 clinical outcomes data presented here are consistent with and strengthen these findings showing that early use of REGEN-COV in outpatients with risk factors for severe Covid-19 can lower the risk of hospitalization or death from any cause. Both doses of intravenous REGEN-COV (1200 mg and 2400 mg) led to a reduction in Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause over a period of 28 days after treatment. The small number of deaths limited the ability to assess the effects of REGEN-COV on mortality. In patients who were hospitalized, REGEN-COV led to a shorter duration of hospitalization and a lower incidence of ICU-level care. In addition, at both doses, REGEN-COV resulted in more rapid resolution of Covid-19 symptoms by a median of 4 days than placebo. Therefore, a single dose of REGEN-COV in outpatients with Covid-19 has the potential to improve patient outcomes and reduce the health care burden during this pandemic by reducing morbidity, including hospitalizations and ICU-level care. Furthermore, REGEN-COV can speed up recovery from Covid-19, which is an additional benefit for patients because there is a growing body of evidence that some patients, including those with mild symptoms, will have a variably prolonged course of recovery.19-21

We previously hypothesized that although host factors play a role in the disease course, the risk of illness and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection may be influenced by a higher viral burden, such that early use of an anti-spike monoclonal antibody combination could reduce this risk.16 In support of this hypothesis, we found that patients in the placebo group who had a Covid-19–related hospitalization or died had higher baseline viral loads and cleared virus more slowly than those in the placebo group who were not hospitalized or did not die. Since we have found that a higher baseline viral load is associated with baseline SARS-CoV-2–seronegative status, the effect of baseline serologic status in patients who received placebo was similarly evaluated in this portion of the trial. In the initial analysis involving the first 275 patients in the phase 1–2 portion of this trial, we found that among patients who received placebo, those who were serum antibody–negative at baseline had a higher incidence of Covid-19–related medically attended visits than those who were serum antibody–positive at baseline. In contrast, in this larger phase 3 data set, patients in the placebo group who were serum antibody–positive at baseline had a similar incidence of hospitalization or death as those who were serum antibody–negative. This suggests that some serum antibody–positive patients have an ineffective immune response, consistent with the finding that among the patients who received placebo in this trial, those who were serum antibody–positive and had a Covid-19–related hospitalization or who died had high baseline viral load levels similar to the levels in those who were serum antibody–negative and had these events. Moreover, this trial showed that REGEN-COV is associated with clinical benefit, regardless of baseline serum antibody status, so that serologic testing at the time of the Covid-19 diagnosis is less critical for making clinical treatment decisions.

Both the 1200-mg and 2400-mg doses of REGEN-COV had similar antiviral and clinical efficacy. This finding suggests that, in this trial, REGEN-COV concentrations were above the minimally effective dose. Both doses reduced viral loads, particularly in patients with higher viral loads, with a faster time to viral clearance than placebo.

Low incidences of serious adverse events, hypersensitivity reactions, and infusion-related reactions were observed. Similar to results reported previously,16 the concentrations of each antibody in serum from the end of infusion through day 29 were well above the predicted neutralization target concentration based on in vitro and preclinical data.

The emergence of resistant variants of SARS-CoV-2 during treatment with an antiviral agent or agents or by circulation within the global community will continue to be a challenge in the development of effective Covid-19 therapeutic agents and vaccines. In vitro studies and in vivo animal studies have shown that combinations of noncompeting antibody-based therapeutics, such as REGEN-COV, are able to suppress the emergence of resistant variants.12-14 REGEN-COV was also found to protect against the selection of SARS-CoV-2 variants in an analysis of spike protein genetic diversity involving 1000 patients with Covid-19 (either outpatients from this trial or hospitalized patients from a separate trial [ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04426695]).14 Moreover, the REGEN-COV combination antibody therapy has had efficacy in vitro against currently circulating variants of concern and variants of interest, including B.1.1.7 (alpha), B.1.351 (beta), B.1.617.2 (delta), and P.1 (gamma).9,14

The 2400-mg dose of REGEN-COV received an emergency use authorization (EUA) from the Food and Drug Administration in November 2020 for the treatment of high-risk outpatients with mild-to-moderate Covid-19.22 In June 2021, after this trial showed that the 1200-mg dose provided a similar decrease in the risk of hospitalization or death and a virologic efficacy that was similar to that provided by the 2400-mg dose, the 1200-mg dose received an EUA (replacing the 2400-mg dose).22 REGEN-COV has also been included in the National Institutes of Health treatment guidelines for high-risk outpatients with Covid-19.23 The data from this phase 3 trial involving outpatients with Covid-19 showed that the 1200-mg dose of REGEN-COV, like the 2400-mg dose, reduced the risk of Covid-19–related hospitalization or death and sped the time to recovery.

Acknowledgments

We thank the trial participants; their families; the investigational site members involved in this trial (principal and subprincipal investigators, listed in the Supplementary Appendix); the Regeneron trial team (members listed in the Supplementary Appendix); the members of the independent data and safety monitoring committee; Brian Head, Ph.D., Caryn Trbovic, Ph.D., and S. Balachandra Dass, Ph.D., of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals for assistance with development of an earlier version of the manuscript; and Prime for assistance with the formatting and copy editing of an earlier version of the manuscript.

Protocol

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

Data Sharing Statement

This article was published on September 29, 2021, at NEJM.org.

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority of the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (contract number HHSO100201700020C).

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. (https://covid19.who.int/table). [Google Scholar]

- 2.People with certain medical conditions. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021. (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 2020;323:1775-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stokes EK, Zambrano LD, Anderson KN, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 case surveillance — United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:759-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020;584:430-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020;323:1239-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Challen R, Brooks-Pollock E, Read JM, Dyson L, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Danon L. Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study. BMJ 2021;372:n579-n579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies NG, Abbott S, Barnard RC, et al. Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Science 2021;372(6538):eabg3055-eabg3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang P, Nair MS, Liu L, et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature 2021;593:130-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie X, Liu Y, Liu J, et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike 69/70 deletion, E484K and N501Y variants by BNT162b2 vaccine-elicited sera. Nat Med 2021;27:620-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen J, Baum A, Pascal KE, et al. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science 2020;369:1010-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baum A, Fulton BO, Wloga E, et al. Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Science 2020;369:1014-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baum A, Ajithdoss D, Copin R, et al. REGN-COV2 antibodies prevent and treat SARS-CoV-2 infection in rhesus macaques and hamsters. Science 2020;370:1110-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Copin R, Baum A, Wloga E, et al. The monoclonal antibody combination REGEN-COV protects against SARS-CoV-2 mutational escape in preclinical and human studies. Cell 2021;184(15):3949-3961.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGEN-COV antibody cocktail in outpatients with Covid-19. June 12, 2021. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.09.21257915v1). preprint.

- 16.Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021;384:238-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rofail D, McGale N, Im J, et al. Development and content validation of the Symptoms Evolution of COVID-19: a patient-reported electronic daily diary in clinical and real-world studies. July 7, 2021. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.06.21259654v1). preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Farrington CP, Manning G. Test statistics and sample size formulae for comparative binomial trials with null hypothesis of non-zero risk difference or non-unity relative risk. Stat Med 1990;9:1447-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del Rio C, Collins LF, Malani P. Long-term health consequences of COVID-19. JAMA 2020;324:1723-1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, et al. Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(2):e210830-e210830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 2021;27:601-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Letter of authorization for emergency use of REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab). Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration, 2021. (https://www.fda.gov/media/145610/download). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 2021. (https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.